A new method for dating ancient earthquakes

Constraining the history of earthquakes produced by bedrock fracturing is important for predicting seismic activity and plate tectonic evolution. In a new study published in the Nature journal Scientific Reports Jan 17, 2020, a team of researchers presents a new microscale technique to determine the age of crystals grown during repeated activation of natural rock fractures over a time range of billions of years.

The dramatic energy release of an earthquake forms as bedrock segments move in relative opposite directions to each other due to the collision or spreading of the tectonic plates that makes up the Earth's crust. The movement occurs along fault planes where new mineral crystals grow simultaneously.

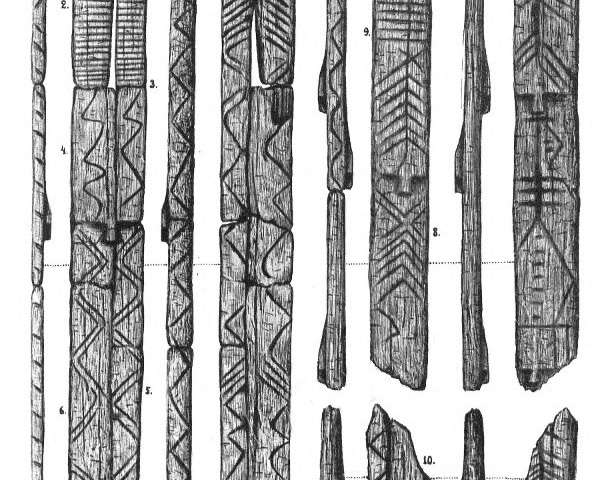

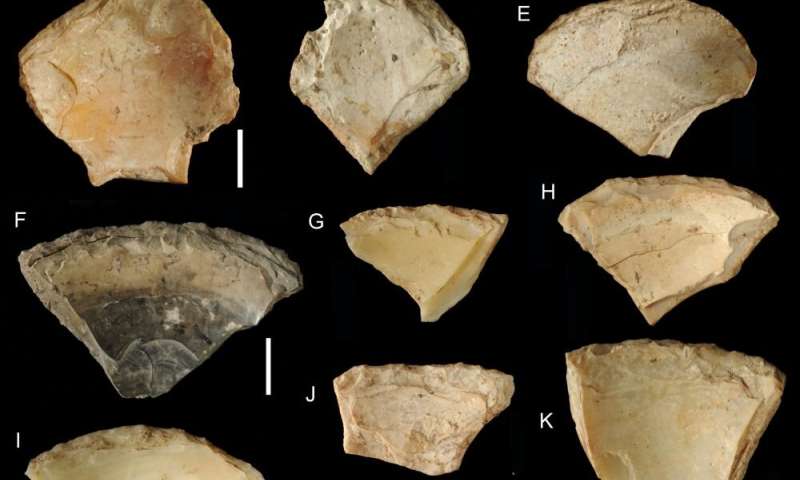

The bedrock of Scandinavia, up to two billion years old, displays an extensive network of fractures formed at different episodes stretching from the early history of the Scandinavian crust to modern times. In rock samples retrieved from deep boreholes in Sweden, new microscale radioisotopic dating of individual fault crystals reveals the dominant fracturing episodes affecting Scandinavia.

Mikael Tillberg, a doctoral student at the Linnaeus University, Sweden, and first author of the paper, explains, "The ages of our analysed crystals matches several distinct periods of extensive mountain range formation when plate boundaries were directly neighboring Scandinavia. These temporal constraints demonstrate that our newly developed approach is suitable to untangle complex fracturing histories."

Thomas Zack, of Gothenburg University, Sweden, and a co-author of the study, describes how the dating method works. "Specific minerals contain radiogenic elements where certain isotopes decay over time. The abundances of these isotopes in tiny crystals formed on fracture surfaces are measured with high precision and detailed spatial resolution."

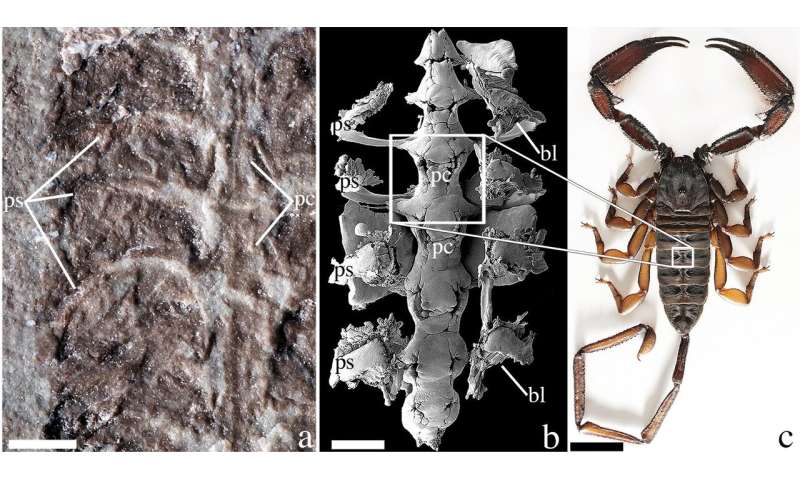

"The link between crystal growth and the frictional movement of earthquakes is ensured by identifying striation lines formed on fracture surface crystals by the movement. This microscopic investigation precedes age analysis to enable a simple and robust procedure for dating of faulting," Henrik Drake at Linnaeus University, also a co-author, adds.

Mikael Tillberg summarizes on the significance and possible future applications of this technique:

"Repeated earthquake episodes produce a chaotic array of broken rock and mineral growth even in a single crystal or on a particular fracture surface. Our methodology can resolve these sequences and connect the microscale mechanisms involved in fracturing to continent-wide plate tectonic forces. This allows reconstruction of geological models for diverse applications such as seismicity and infrastructure engineering."

More information: Mikael Tillberg et al. In situ Rb-Sr dating of slickenfibres in deep crystalline basement faults, Scientific Reports (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-019-57262-5