Sadie American Explains at London Convention Work Done to Check Evil.

GATHERING A NOTABLE ONE

Chief Rabbi Adler, Lord Swaythling,

Leopold do Rothschild, and Claude Montefiore Among Those Present.

Special Cable to THE NEW YORK TIMES.

April 10, 1910

Credit...The New York Times Archives

See the article in its original context from

April 10, 1910, Section S, Page 4

LONDON, April 9 -- Miss Sadie American, the President of the Council of Jewish Women of New York, was present at the three days' convention of the Jewish International Conference held in London this week under the Chairmanship of Claude Montefiore. Others present included Chief Rabbi Adler, Lord and Lady Swaythling, Lady Battersea, and Leopold de Rothschild. VIEW FULL ARTICLE IN TIMESMACHINE »

This book recounts the events involving Raquel Liberman, an impoverished immigrant to Argentina that was forced by circumstances into prostitution, and the powerful Zwi Migdal, which controlled the recruitment and deployment of Jewish prostitutes in Argentina while maintaining mutually profitable relations with corrupt politicians and policemen. Liberman's story is presented as an example of individual courage and determination in the face of the violence and corruption of the prostitution business. Her struggle with the Zwi Migdal and triumphant public victory over her oppressors was widely publicized in newspapers and magazines, and was a political cause celebre in its time. This book gives readers an intimate view of how the affair caught the public imagination, and was interpreted and transformed by the artistic imagination.

The Nation of Islam's Secret Relationship between Blacks and Jews has been called one of the most serious anti-Semitic manuscripts published in years. This work of so-called scholars received great celebrity from individuals like Louis Farrakhan, Leonard Jeffries, and Khalid Abdul Muhammed who used the document to claim that Jews dominated both transatlantic and antebellum South slave trades. As Saul Friedman definitively documents in Jews and the American Slave Trade, historical evidence suggests that Jews played a minimal role in the transatlantic, South American, Caribbean, and antebellum slave trades.Jews and the American Slave Trade dissects the questionable historical technique employed in Secret Relationship, offers a detailed response to Farrakhan's charges, and analyzes the impetus behind these charges. He begins with in-depth discussion of the attitudes of ancient peoples, Africans, Arabs, and Jews toward slavery and explores the Jewish role hi colonial European economic life from the Age of Discovery tp Napoleon. His state-by-state analyses describe in detail the institution of slavery in North America from colonial New England to Louisiana. Friedman elucidates the role of American Jews toward the great nineteenth-century moral debate, the positions they took, and explains what shattered the alliance between these two vulnerable minority groups in America.Rooted in incontrovertible historical evidence, provocative without being incendiary, Jews and the American Slave Trade demonstrates that the anti-slavery tradition rooted in the Old Testament translated into powerful prohibitions with respect to any involvement in the slave trade. This brilliant exploration will be of interest to scholars of modern Jewish history, African-American studies, American Jewish history, U.S. history, and minority studies.

In the wake of the civil rights movement, a great divide has opened up between African American and Jewish communities. What was historically a harmonious and supportive relationship has suffered from a powerful and oft-repeated legend, that Jews controlled and masterminded the slave trade and owned slaves on a large scale, well in excess of their own proportion in the population.

In this groundbreaking book, likely to stand as the definitive word on the subject, Eli Faber cuts through this cloud of mystification to recapture an important chapter in both Jewish and African diasporic history.

Focusing on the British empire, Faber assesses the extent to which Jews participated in the institution of slavery through investment in slave trading companies, ownership of slave ships, commercial activity as merchants who sold slaves upon their arrival from Africa, and direct ownership of slaves. His unprecedented original research utilizing shipping and tax records, stock-transfer ledgers, censuses, slave registers, and synagogue records reveals, once and for all, the minimal nature of Jews' involvement in the subjugation of Africans in the Americas.

A crucial corrective, Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade lays to rest one of the most contested historical controversies of our time.

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/2020/01/the-universal-cause-history-of.html

Special Cable to THE NEW YORK TIMES.

April 10, 1910

Credit...The New York Times Archives

See the article in its original context from

April 10, 1910, Section S, Page 4

LONDON, April 9 -- Miss Sadie American, the President of the Council of Jewish Women of New York, was present at the three days' convention of the Jewish International Conference held in London this week under the Chairmanship of Claude Montefiore. Others present included Chief Rabbi Adler, Lord and Lady Swaythling, Lady Battersea, and Leopold de Rothschild. VIEW FULL ARTICLE IN TIMESMACHINE »

This book recounts the events involving Raquel Liberman, an impoverished immigrant to Argentina that was forced by circumstances into prostitution, and the powerful Zwi Migdal, which controlled the recruitment and deployment of Jewish prostitutes in Argentina while maintaining mutually profitable relations with corrupt politicians and policemen. Liberman's story is presented as an example of individual courage and determination in the face of the violence and corruption of the prostitution business. Her struggle with the Zwi Migdal and triumphant public victory over her oppressors was widely publicized in newspapers and magazines, and was a political cause celebre in its time. This book gives readers an intimate view of how the affair caught the public imagination, and was interpreted and transformed by the artistic imagination.

The Nation of Islam's Secret Relationship between Blacks and Jews has been called one of the most serious anti-Semitic manuscripts published in years. This work of so-called scholars received great celebrity from individuals like Louis Farrakhan, Leonard Jeffries, and Khalid Abdul Muhammed who used the document to claim that Jews dominated both transatlantic and antebellum South slave trades. As Saul Friedman definitively documents in Jews and the American Slave Trade, historical evidence suggests that Jews played a minimal role in the transatlantic, South American, Caribbean, and antebellum slave trades.Jews and the American Slave Trade dissects the questionable historical technique employed in Secret Relationship, offers a detailed response to Farrakhan's charges, and analyzes the impetus behind these charges. He begins with in-depth discussion of the attitudes of ancient peoples, Africans, Arabs, and Jews toward slavery and explores the Jewish role hi colonial European economic life from the Age of Discovery tp Napoleon. His state-by-state analyses describe in detail the institution of slavery in North America from colonial New England to Louisiana. Friedman elucidates the role of American Jews toward the great nineteenth-century moral debate, the positions they took, and explains what shattered the alliance between these two vulnerable minority groups in America.Rooted in incontrovertible historical evidence, provocative without being incendiary, Jews and the American Slave Trade demonstrates that the anti-slavery tradition rooted in the Old Testament translated into powerful prohibitions with respect to any involvement in the slave trade. This brilliant exploration will be of interest to scholars of modern Jewish history, African-American studies, American Jewish history, U.S. history, and minority studies.

In the wake of the civil rights movement, a great divide has opened up between African American and Jewish communities. What was historically a harmonious and supportive relationship has suffered from a powerful and oft-repeated legend, that Jews controlled and masterminded the slave trade and owned slaves on a large scale, well in excess of their own proportion in the population.

In this groundbreaking book, likely to stand as the definitive word on the subject, Eli Faber cuts through this cloud of mystification to recapture an important chapter in both Jewish and African diasporic history.

Focusing on the British empire, Faber assesses the extent to which Jews participated in the institution of slavery through investment in slave trading companies, ownership of slave ships, commercial activity as merchants who sold slaves upon their arrival from Africa, and direct ownership of slaves. His unprecedented original research utilizing shipping and tax records, stock-transfer ledgers, censuses, slave registers, and synagogue records reveals, once and for all, the minimal nature of Jews' involvement in the subjugation of Africans in the Americas.

A crucial corrective, Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade lays to rest one of the most contested historical controversies of our time.

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/2020/01/the-universal-cause-history-of.html

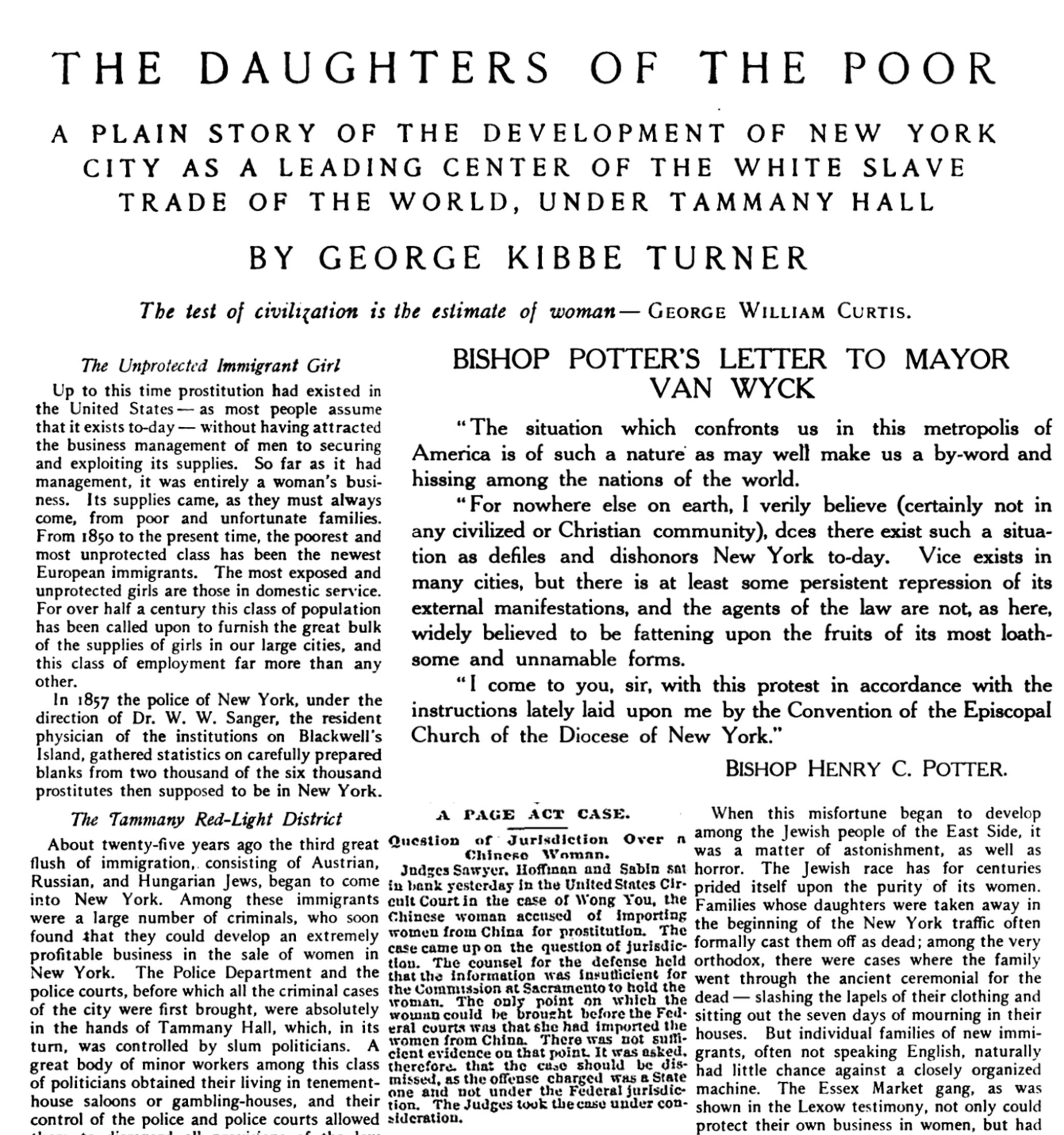

' WHITE SLAVE' TRADE IS NOT ORGANIZEDSo Says the Rockefeller Grand Jury's Presentment, at Last Filed with the Court. NYT ARCHIVE June 29, 1910