Larry Elliott

What initially seemed localised is worldwide and economic pain will go on for longer than first thought

Mon 16 Mar 2020

What initially seemed localised is worldwide and economic pain will go on for longer than first thought

Mon 16 Mar 2020

If people do not go out to their weekly meal

at their favourite local restaurant for the next

two months they are not going to eat out four

times a week when the fear of infection has

been lifted. Photograph: Andy Rain/EPA

Travel bans. Sporting events cancelled. Mass gatherings prohibited. Stock markets in freefall. Deserted shopping malls. Get ready for the Covid-19 global recession.

Up until a month ago this seemed far-fetched. It was assumed that the coronavirus outbreak would be a localised problem for China and that any spillover effects to the rest of the world could be comfortably managed by a bit of policy easing by central banks.

When it became clear that Covid-19 was not confined to China and that the economic effects would be more widespread, forecasts started to be revised down. But central banks, finance ministries and independent economists took comfort from the fact that there would be a sharp but short hit to activity followed by a rapid return to business as usual.

This line of thinking has exact parallels with the events of 2007, when it was initially assumed that the subprime mortgage crisis was a minor and manageable problem affecting only the US – and nobody needs reminding how that ended.

If history is any guide, the global economy will eventually recover from the Covid-19 pandemic, but the idea that this is going to be a V-shaped recession in the first half of 2020 followed by a recovery in the second half of the year looks absurd after the tumultuous events of the past week.

What’s more, policymakers know as much. The Federal Reserve – the US central bank – did not need to be told by Donald Trump that it needed to cut interest rates and resume large-scale asset purchases known as quantitative easing. The world’s most powerful central bank pulled out the stops on Sunday night by slashing rates to nearly zero and pledging to expand its balance sheet by $700bn.

In the coming weeks the Bank of England can be expected to cut interest rates to 0.1%

In the UK the coordinated response by the Bank of England and the Treasury last week was seen as a textbook example of how policymakers ought to respond to the crisis. It was, though, only the start. Airline companies will quickly go bust unless they receive financial assistance. The same goes for retailers, many of them hanging on by their fingertips even before Covid-19. Britain has a new chancellor of the exchequer in Rishi Sunak and, from Monday, a new governor of the Bank of England in Andrew Bailey, and they will both be aware that the risks of doing too little too late are far greater than those of doing too much too soon.

So, in the coming weeks the Bank can be expected to cut interest rates to 0.1% – the lowest they have ever been – and to resume its QE programme. Sunak will have to add to the £12bn he has set aside to deal with Covid-19.

As in 2008-09, the authorities in the eurozone have been slowest to act but there have been welcome signs in recent days – from Germany, most significantly – of the need for governments to spend, and spend big.

It has been clear from the start that Covid-19 affects both sides of the economy: supply and demand. The supply of goods and services is impaired because factories and offices are shut and output falls as a result. But demand also falls because consumers stay at home and stop spending, and businesses mothball investment.

Conventional policy measures – such as cutting the cost of borrowing or reducing taxes – tend to work better when there is a demand shock. There is a limit to what they can do in the event of a combined supply and demand shock.

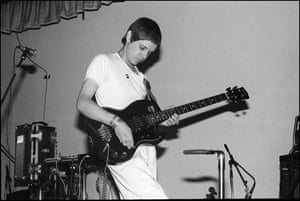

Italy is in lockdown because of the coronavirus.

Travel bans. Sporting events cancelled. Mass gatherings prohibited. Stock markets in freefall. Deserted shopping malls. Get ready for the Covid-19 global recession.

Up until a month ago this seemed far-fetched. It was assumed that the coronavirus outbreak would be a localised problem for China and that any spillover effects to the rest of the world could be comfortably managed by a bit of policy easing by central banks.

When it became clear that Covid-19 was not confined to China and that the economic effects would be more widespread, forecasts started to be revised down. But central banks, finance ministries and independent economists took comfort from the fact that there would be a sharp but short hit to activity followed by a rapid return to business as usual.

This line of thinking has exact parallels with the events of 2007, when it was initially assumed that the subprime mortgage crisis was a minor and manageable problem affecting only the US – and nobody needs reminding how that ended.

If history is any guide, the global economy will eventually recover from the Covid-19 pandemic, but the idea that this is going to be a V-shaped recession in the first half of 2020 followed by a recovery in the second half of the year looks absurd after the tumultuous events of the past week.

What’s more, policymakers know as much. The Federal Reserve – the US central bank – did not need to be told by Donald Trump that it needed to cut interest rates and resume large-scale asset purchases known as quantitative easing. The world’s most powerful central bank pulled out the stops on Sunday night by slashing rates to nearly zero and pledging to expand its balance sheet by $700bn.

In the coming weeks the Bank of England can be expected to cut interest rates to 0.1%

In the UK the coordinated response by the Bank of England and the Treasury last week was seen as a textbook example of how policymakers ought to respond to the crisis. It was, though, only the start. Airline companies will quickly go bust unless they receive financial assistance. The same goes for retailers, many of them hanging on by their fingertips even before Covid-19. Britain has a new chancellor of the exchequer in Rishi Sunak and, from Monday, a new governor of the Bank of England in Andrew Bailey, and they will both be aware that the risks of doing too little too late are far greater than those of doing too much too soon.

So, in the coming weeks the Bank can be expected to cut interest rates to 0.1% – the lowest they have ever been – and to resume its QE programme. Sunak will have to add to the £12bn he has set aside to deal with Covid-19.

As in 2008-09, the authorities in the eurozone have been slowest to act but there have been welcome signs in recent days – from Germany, most significantly – of the need for governments to spend, and spend big.

It has been clear from the start that Covid-19 affects both sides of the economy: supply and demand. The supply of goods and services is impaired because factories and offices are shut and output falls as a result. But demand also falls because consumers stay at home and stop spending, and businesses mothball investment.

Conventional policy measures – such as cutting the cost of borrowing or reducing taxes – tend to work better when there is a demand shock. There is a limit to what they can do in the event of a combined supply and demand shock.

Italy is in lockdown because of the coronavirus.

Photograph: Antonio Masiello/Getty Images

Policymakers know that, which is why Sunak stressed in his budget speech that the economy faced a tough period. The aim is make the downturn as short and shallow as possible, even though the chances of this look vanishingly small.

One reason for that is because the economic disruption caused by Covid-19 is enormous. Entire countries – Italy and Spain – are in lockdown. The problems facing airline companies are symptomatic of a crisis facing the global travel industry, from cruise companies to hotels that cater for tourists. Discretionary spending by consumers appears to have collapsed in recent days.

Despite globalisation, much economic activity remains local but here, too, there will be an impact as people cancel appointments at the dentist, put off having their hair cut and wait to put their house on the market.

Paul Dales, the chief UK economist at Capital Economics, has estimated that output in Britain will shrink by 2.5% in the second quarter but says a 5% fall is possible. The more pessimistic estimate looks quite plausible.Sign up to the daily Business Today email or follow Guardian Business on Twitter at @BusinessDesk

What’s more, in a service-sector dominated economy much of the lost output is never going to be recovered. If people do not go out to their weekly meal at their favourite local restaurant for the next two months they are not going to eat out four times a week when the fear of infection has been lifted.

It also seems likely that the economic pain will go on for longer than originally estimated. Having imposed bans and restrictions, governments and private-sector bodies will be cautious about removing them. Countries such as Italy will be wary of opening their borders while there is a fear of reinfection. The idea that Premier League football will be back by early April is fanciful.

There is also a question of how long it will take consumer and business confidence to recover. Policy action by central banks and finance ministries can help in this respect but only so much. The chances are that the imminent recession will be U-shaped: a steep decline followed by a period of bumping along the bottom. There will be recovery but it will take time and only after much damage has been caused.

Policymakers know that, which is why Sunak stressed in his budget speech that the economy faced a tough period. The aim is make the downturn as short and shallow as possible, even though the chances of this look vanishingly small.

One reason for that is because the economic disruption caused by Covid-19 is enormous. Entire countries – Italy and Spain – are in lockdown. The problems facing airline companies are symptomatic of a crisis facing the global travel industry, from cruise companies to hotels that cater for tourists. Discretionary spending by consumers appears to have collapsed in recent days.

Despite globalisation, much economic activity remains local but here, too, there will be an impact as people cancel appointments at the dentist, put off having their hair cut and wait to put their house on the market.

Paul Dales, the chief UK economist at Capital Economics, has estimated that output in Britain will shrink by 2.5% in the second quarter but says a 5% fall is possible. The more pessimistic estimate looks quite plausible.Sign up to the daily Business Today email or follow Guardian Business on Twitter at @BusinessDesk

What’s more, in a service-sector dominated economy much of the lost output is never going to be recovered. If people do not go out to their weekly meal at their favourite local restaurant for the next two months they are not going to eat out four times a week when the fear of infection has been lifted.

It also seems likely that the economic pain will go on for longer than originally estimated. Having imposed bans and restrictions, governments and private-sector bodies will be cautious about removing them. Countries such as Italy will be wary of opening their borders while there is a fear of reinfection. The idea that Premier League football will be back by early April is fanciful.

There is also a question of how long it will take consumer and business confidence to recover. Policy action by central banks and finance ministries can help in this respect but only so much. The chances are that the imminent recession will be U-shaped: a steep decline followed by a period of bumping along the bottom. There will be recovery but it will take time and only after much damage has been caused.