The SUTD study will be crucial for assessing future climatic changes and making more informed water management decisions.

IMAGE: MAP OF THE ASIAN MONSOON REGION; RIVER BASINS INVOLVED IN THIS STUDY ARE HIGHLIGHTED BY SUBREGION, RIVERS BELONGING TO THE WORLD'S 30 BIGGEST ARE SHOWN WITH NAMES INDICATED IN BLUE.... view more

CREDIT: SUTD

813 years of annual river discharge at 62 stations, 41 rivers in 16 countries, from 1200 to 2012. That is what researchers at the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) produced after two years of research in order to better understand past climate patterns of the Asian Monsoon region.

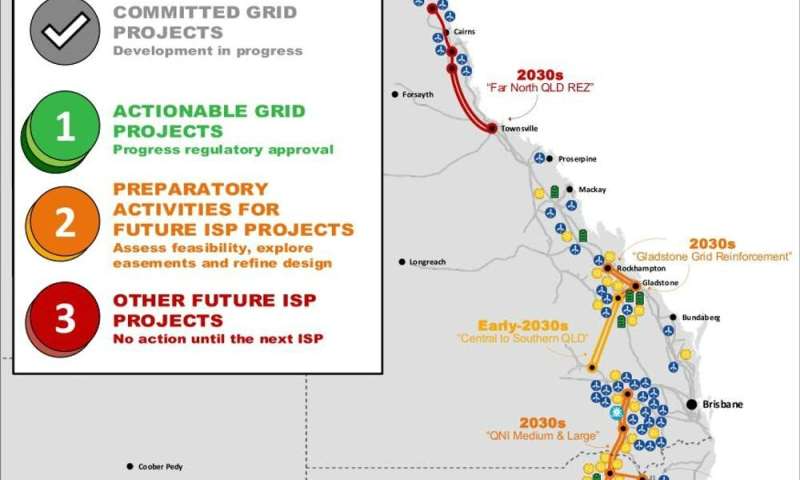

Home to many populous river basins, including ten of the world's biggest rivers (Figure 1), the Asian Monsoon region provides water, energy, and food for more than three billion people. This makes it crucial for us to understand past climate patterns so that we can better predict long term changes in the water cycle and the impact they will have on the water supply.

To reconstruct histories of river discharge, the researchers relied on tree rings. An earlier study by Cook et al. (2010) developed an extensive network of tree ring data sites in Asia and created a paleodrought record called the Monsoon Asia Drought Atlas (MADA). SUTD researchers used the MADA as an input for their river discharge model.

They developed an innovative procedure to select the most relevant subset of the MADA for each river based on hydroclimatic similarity. This procedure allowed the model to extract the most important climate signals that influence river discharge from the underlying tree ring data.

"Our results reveal that rivers in Asia behave in a coherent pattern. Large droughts and major pluvial periods have often occurred simultaneously in adjacent or nearby basins. Sometimes, droughts stretched as far as from the Godavari in India to the Mekong in Southeast Asia (Figure 2). This has important implications for water management, especially when a country's economy depends on multiple river basins, like in the case of Thailand," explained first author Nguyen Tan Thai Hung, a PhD student from SUTD.

Using modern measurements, it has been known that the behaviour of Asian rivers is influenced by the oceans. For instance, if the Pacific Ocean becomes warmer in its tropical region in an El Nino event, this will alter atmospheric circulations and likely cause droughts in South and Southeast Asian rivers. However, the SUTD study revealed that this ocean-river connection is not constant over time. The researchers found that rivers in Asia were much less influenced by the oceans in the first half of the 20th century compared to the 50 years before and 50 years after that period.

"This research is of great importance to policy makers; we need to know where and why river discharge changed during the past millennium to make big decisions on water-dependent infrastructure. One such example is the development of the ASEAN Power Grid, conceived to interconnect a system of hydropower, thermoelectric, and renewable energy plants across all ASEAN countries. Our records show that 'mega-droughts' have hit multiple power production sites simultaneously, so we can now use this information to design a grid that is less vulnerable during extreme events," said principal investigator Associate Professor Stefano Galelli from SUTD.

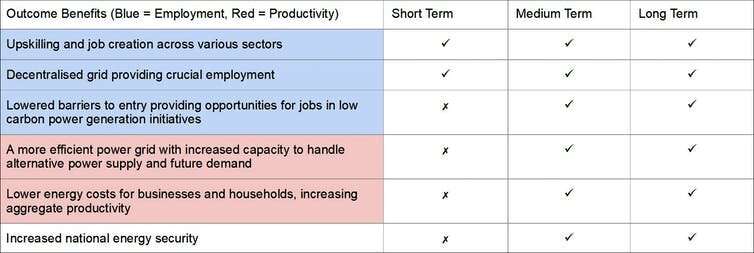

CAPTION

This "heat map" shows the reconstructed history of 62 river reaches (each row) over 812 years (each column). The stations are arranged approximately north to south (top down on y?axis) and divided into five regions as delineated in Figure 1: CA (Central Asia), EA (East Asia), WA (West Asia), CN (eastern China), SEA (Southeast Asia), and SA (South Asia).

A stand of 80- to 85-year-old longleaf pines and an open, grassy area where seedlings can grow unhampered—including a few at the top of the shadow are seen in the DeSoto National Forest in Miss. Landowners and government agencies in nine states from Texas to Virginia are working to bring back longleaf pines, planting seedlings in some areas and managing others to remove shrubs and other kinds of trees. (AP Photo/Janet McConnaughey)

A stand of 80- to 85-year-old longleaf pines and an open, grassy area where seedlings can grow unhampered—including a few at the top of the shadow are seen in the DeSoto National Forest in Miss. Landowners and government agencies in nine states from Texas to Virginia are working to bring back longleaf pines, planting seedlings in some areas and managing others to remove shrubs and other kinds of trees. (AP Photo/Janet McConnaughey)