Conspiracy theories and the ‘American Madness’ that gripped the Capitol

Author Tea Krulos talked to Religion News Service about how conspiracy theories have spread, how religion plays a role and how to talk to friends and family who believe them.

(RNS) — Tea Krulos was introduced to conspiracy theories on TV shows like “The X-Files,” popular in the 1990s.

It all seemed to him like fun and games, or aliens and shadowy government figures, until the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut.

RELATED: Russell Moore, Justin Giboney warn that conspiracies must be confronted with truth

That’s when conspiracy theorists — convinced the shooting had been faked by the government to strip Americans of their Second Amendment rights — began harassing the grieving families of 26 murdered children and school staff. And it’s when Krulos realized how deep and dark conspiracies could become.

“It’s just so crazy to think about how much this has changed in the last 10 years or even in the last five years — or even in the last year. It’s just been progressively building more and more steam,” he said.

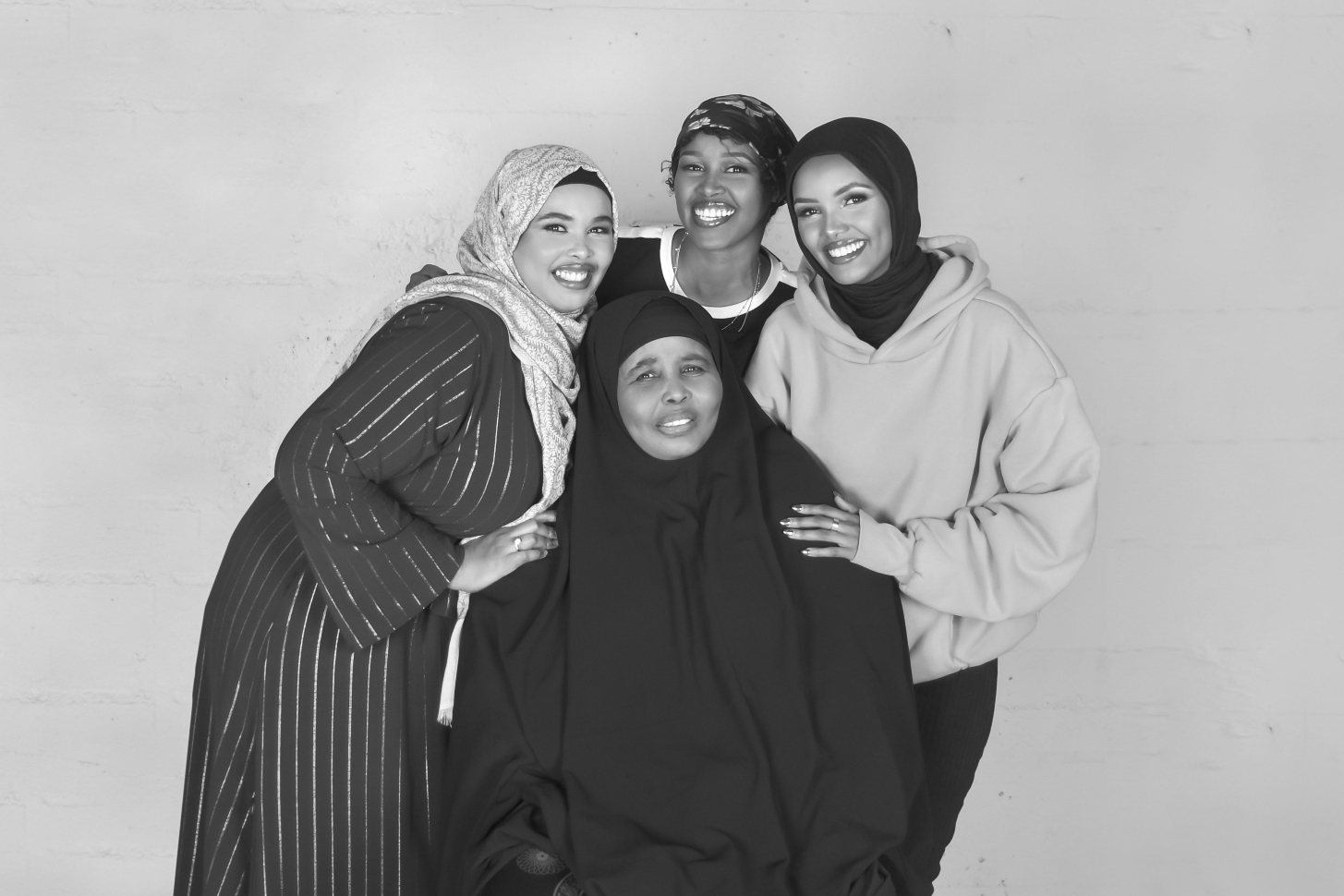

“American Madness: The Story of the Phantom Patriot and How Conspiracy Theories Hijacked American Consciousness” by Tea Krulos. Courtesy image

The Milwaukee-based freelance journalist — who previously has profiled subcultures in books about paranormal enthusiasts and doomsday preppers — most recently turned his pen to conspiracy theorists in his book “American Madness: The Story of the Phantom Patriot and How Conspiracy Theories Hijacked American Consciousness.”

In it, Krulos follows the story of Richard McCaslin, who spent time in prison after raiding California’s Bohemian Grove in 2002 as his costumed alter ego, the Phantom Patriot, hoping to expose the child sacrifices and satanic ceremonies he believed world leaders were conducting there. McCaslin later died by suicide.

Krulos sees echoes of McCaslin’s story in headlines about Pizzagate and the Nashville bomber, who reportedly believed a popular conspiracy theory that lizard people called Reptilians control the world. He also sees the culmination of many conspiracy theories in last week’s siege of the U.S. Capitol.

“This last year has just been one giant conspiracy theory about everything — the pandemic, the civil unrest, the election — and it all sort of culminated with this terrifying scene we saw on Jan. 6. That was an army of conspiracy theorists, pretty much,” he said.

Krulos talked to Religion News Service about how conspiracy theories have spread, how religion plays a role and how to talk to friends and family who believe them.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you get interested in the Phantom Patriot and the wider world of conspiracy theories?

In 2010, I was working on my first book, “Heroes in the Night,” which was about the Real-Life Superhero subculture. Richard found my blog and was reading it, and then he sent me a message. It turned into this almost 10-year project of interviewing him and researching the conspiracy theories he was telling me about.

I think the book added another layer probably around 2015, which was when (Donald) Trump was campaigning for president. I noticed one of the first media appearances he did after he announced he was running for president was on “The Alex Jones Show” on Infowars. Alex Jones had been a big influence on Richard and his raid into the Bohemian Grove. So I was like, there’s a connection here: Richard, Alex Jones, Donald Trump.

And then, of course, the conspiracy craziness really began. I was like: This is not a unique story. It’s a story that’s repeating itself. People are getting influenced by these conspiracies and they’re being driven into extremism because of it.

Author Tea Krulos. Photo by Megan Berendt/Creative Commons

How did conspiracy theories, as you write, hijack American consciousness?

The key ingredients in conspiracy are a lot of fear and anger and division among people, and we’ve just had so much of that, especially in this era. So I think people are really primed to be influenced by this stuff. And the internet is such a huge part of the problem. I think it’s so easy to create misinformation that looks like it could be legit. I see people telling people they need to fact-check stuff, and I’m glad, but a lot of times people don’t want to fact-check it. They see something that confirms this bias they have, and they’re like, “That sounds right to me, and so it’s fact to me.”

It has such an incredible fast and far reach, and I think this year has been especially bad because you have so many people stuck at home on the internet, so they start going down these rabbit holes. At first it might be just kind of a curiosity, but it sucks them in.

RELATED: Heathens condemn storming of Capitol after Norse religious symbols appear amid mob

How did you see this culminate Wednesday?

The details are still coming out, and the details are just awful. I’m not at all surprised, but guess who was there in the crowd (at a rally outside) riling everyone up with a bullhorn? Alex Jones himself. Lots of QAnon influencers were at the event. In fact, one of the first guys who broke into the building had a Q T-shirt on. And then, of course, the media loves showing images of this guy who calls himself the “QAnon Shaman.”

But, you know, you can’t just paint it as fringe nuts, because there were elected officials who were part of that crowd.

Trump supporters gesture to U.S. Capitol Police in the hallway outside of the Senate chamber at the Capitol in Washington on Jan. 6, 2021. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

Who are conspiracy theorists?

It seems like everyone has people in their lives who, to varying degrees, believe some of this stuff.

I don’t think it’s relegated to just, you know, blue-collar Trump supporters. There are liberals who spread and share conspiracy theories as well. I think it’s more prevalent now that it’s conservative stuff, just because of Trump being in office and these huge groups like QAnon, but there is a wide range of people who have conspiracy beliefs.

This phrase drives me crazy when conspiracy people use it, and it’s “do your own research.” I think it’s great to read. I think it’s great to be curious about things. But by doing your own research, they’re telling you that you should watch YouTube videos that might look kind of slick because they’re presented in documentary fashion. They have this bad case of what’s called the Dunning-Kruger effect, where they think because they’ve watched these YouTube videos and they read a self-published book they then are equitable in their knowledge to someone who is an actual doctor or someone that works at NASA.

RELATED: How QAnon uses satanic rhetoric to set up a narrative of ‘good vs. evil’ (COMMENTARY)

Religion pops up throughout your book. For one, McCaslin grew up evangelical and his comics were full of references to Scripture. What role does religion play in conspiracy theories and the people who believe in them?

A very strong one. Really QAnon, which is the biggest conspiracy problem today, is just the Satanic Panic all over again. It’s very, very much based on this idea that Trump is a man of God, and he’s engaged in a holy war with the sinister Satan-worshipping cabal of Democrats and other liberals, the media, Hollywood, stuff like that. They are the satanic ring that are pedophiles and cannibals and secretly causing everything awful happening in our country.

Richard McCaslin as his costumed alter ego, the Phantom Patriot, in an undated image. Courtesy photo

For Richard, I think it was very much religion with some comic book stuff mixed in, and both of those combined together made him really see this very black and white. There’s good guys, who are the superheroes, and there’s bad guys, who are satanists, and we’re in this very moral war where you have to pick a side, good or bad.

I found it very interesting, though, that he very suddenly switched to become a Jehovah’s Witness while he was in prison, and then when he got out of prison, he started following the teachings of this conspiracy theorist named David Icke, who really popularized the Reptilian alien theory. After he started following David, he decided to drop religion entirely, and he described himself as being a spiritual person, but no longer a Christian.

So I think that really shows you just how strong some of these conspiracy theorist teachings can be, where they’re so influential people will drop their religion. In some cases, they’ll separate themselves from their family and friends. It’s very cultlike. They’re willing to give up anything — in some cases now, even their lives — because they believe in this stuff.

Last week, Russell Moore and others called on faith leaders to combat the conspiracy theories they say contributed to the mob violence at the Capitol. What can clergy and other leaders do?

I think that’s a great idea. As leaders, they’re in a position where they can, in an empathetic way, talk to people about the dangers of these theories and maybe share some of these stories.

You know, there were four people who died at the Capitol (as well as a Capitol police officer). At first, I had a lot of anger toward this crowd, but one of the women who died was going through a hard time. She had been struggling with drug addiction, and she had talked about someday wanting to be a drug counselor herself. But she had also fallen down this QAnon rabbit hole. She was searching for something to maybe fill this void in her, and she stumbled across QAnon, when she could have filled that with something more positive

What about the rest of us? How can we talk to friends and family members who believe some of the prominent conspiracy theories out there?

It’s really difficult, and I don’t think I have all the answers on this, I’m sad to say. I think being kind and trying to listen to someone and engage in a real conversation with them is something people should try to do, rather than saying, “Oh, you’re so stupid,” or something like that. That’s not going to help at all. Trying to say, you know, “I understand why you would think this, but if you look at legitimate news sources, no one is reporting on this.”

You can try, is the best you can do. A lot of people are just going to completely shut you out, though. It’s sad. There are many, many stories of people who have lost spouses, parents, siblings, really good friends. Their relationships have been severed because a person won’t stop hounding the other person about conspiracy theories.