Planet-Scale MRI

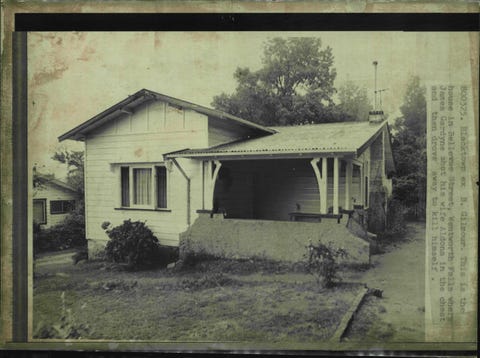

Azimuthal anisotropy (black dashed lines showing the fast direction of wave speeds) in the mantle at 200 km depth plotted on top of vertically polarized shear wave speed perturbations (dVsv) after 20 iterations based on global azimuthally anisotropic adjoint tomography. The maximum peak-to-peak anisotropy is 2.3%. Red and blue colors denote the slow and fast shear wave speeds with respect to the mean model which are generally associated with hot and cold materials, respectively. CREDIT Ebru Bozdag, Colorado School of Mines

Earthquakes do more than buckle streets and topple buildings.

Seismic waves generated by earthquakes pass through the Earth, acting like a giant MRI machine and providing clues to what lies inside the planet.

Seismologists have developed methods to take wave signals from the networks of seismometers at the Earth's surface and reverse engineer features and characteristics of the medium they pass through, a process known as seismic tomography.

For decades, seismic tomography was based on ray theory, and seismic waves were treated like light rays. This served as a pretty good approximation and led to major discoveries about the Earth's interior. But to improve the resolution of current seismic tomographic models, seismologists need to take into account the full complexity of wave propagation using numerical simulations, known as full-waveform inversion, says Ebru Bozdag, assistant professor in the Geophysics Department at the Colorado School of Mines.

"We are at a stage where we need to avoid approximations and corrections in our imaging techniques to construct these models of the Earth's interior," she said.

Bozdag was the lead author of the first full-waveform inversion model, GLAD-M15 in 2016, based on full 3D wave simulations and 3D data sensitivities at the global scale. The model used the open-source 3D global wave propagation solver SPECFEM3D_GLOBE (freely available from Computational Infrastructure for Geodynamics) and was created in collaboration with researchers from Princeton University, University of Marseille, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) and Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL). The work was lauded in the press. Its successor, GLAD-M25 (Lei et al. 2020), came out in 2020 and brought prominent features like subduction zones, mantle plumes, and hotspots into view for further discussions on mantle dynamics.

"We showed the feasibility of using full 3D wave simulations and data sensitivities to seismic parameters at the global scale in our 2016 and 2020 papers. Now, it's time to use better parameterization to describe the physics of the Earth's interior in the inverse problem," she said.

At the American Geophysical Union Fall meeting in December 2021, Bozdag, post-doctoral researcher Ridvan Örsvuran, PhD student Armando Espindola-Carmona and computational seismologist Daniel Peter from KAUST, and collaborators presented the results of their efforts to perform global full waveform inversion to model attenuation -- a measure of the loss of energy as seismic waves propagate within the Earth -- and azimuthal anisotropy - including the way wave speeds vary as a function of propagation direction azimuthally in addition to radial anisotropy taken into account in the first-generation GLAD models.

They uses data from 300 earthquakes to construct the new global full wave inversion models. "We update these Earth models such that the difference from observation and simulated data is minimized iteratively," she said. "And we seek to understand how our model parameters, elastic and anelastic, trade-off with each other, which is a challenging task."

The research is supported by a National Science Foundation (NSF) CAREER award, and enabled by the Frontera supercomputer at the Texas Advanced Computing Center -- the fastest as any university and the 13th fastest overall in the world -- as well as the Marconi100 system at Cineca, the largest Italian computing center.

"With access to Frontera, publicly available data from all around the world, and the power of our modeling tools, we've started approaching the continental-scale resolution in our global full wave inversion models," she said.

Bozdag hopes to provide better constraints on the origin of mantle plumes and the water content of the upper mantle. Furthermore, "to accurately locate earthquakes and other seismic sources, determine earthquake mechanisms and correlate them to plate tectonics better, you need to have high-resolution crustal and mantle models," she said.

FROM THE DEEPEST OCEANS TO OUTER SPACE

Bozdag's work isn't only relevant on Earth. She also shares her expertise in numerical simulations with the NASA's InSight mission as part of the science team to model the interior of Mars.

Preliminary details of the Martian crust, constrained by seismic data for the first time, were published in Science in September 2021. Bozdag, together with the InSight team, is continuing to analyze the marsquake data and resolve details of the planet's interior from the crust to the core with the help of 3D wave simulations performed on Frontera.

The Mars work put in perspective the dearth of data in some parts of the Earth, specifically beneath oceans. "We now have data from other planets, but it is still challenging to have high-resolution images beneath the oceans due to lack of instruments," Bozdag said.

To address that, she is working on integrating data from emerging instruments into her models as part of her NSF CAREER award, such as those from floating acoustic robots known as MERMAIDs (Mobile Earthquake Recording in Marine Areas by Independent Divers). These autonomous submarines can capture seismic activity within the ocean and rise to the surface to deliver that data to scientists.

SEISMIC COMMUNITY ACCESS

In September 2021, Bozdag was part of a team awarded a $3.2 million NSF award to create a computational platform for the seismology community, known as SCOPED (Seismic COmputational Platform for Empowering Discovery), in collaboration with Carl Tape (University of Alaska-Fairbanks), Marine Denolle (University of Washington), Felix Waldhauser (Columbia University), and Ian Wang (TACC).

"The SCOPED project will establish a computing platform, supported by Frontera, that delivers data, computation, and services to the seismological community to promote education, innovation, and discovery," said Wang, TACC research associate and co-principal investigator on the project. "TACC will be focusing on developing the core cyberinfrastructure that serves both compute- and data-intensive research, including seismic imaging, waveform modeling, ambient noise seismology, and precision seismic monitoring."

Another community-oriented project from Bozdag's group is PhD student Caio Ciardelli's recently released SphGLLTools: a visualization toolbox for large seismic model files. The toolbox based facilitates easy plotting and sharing of global adjoint tomography models with the community. The team described the toolbox in Computers & Geosciences in February 2022.

"We provide a full set of computational tools to visualize our global adjoint models," Bozdag said. "Someone can take our models based on HPC simulations and convert them into a format to make it possible to visualize them on personal computers and use collaborative notebooks to understand each step."

Said Robin Reichlin, Director of the Geophysics Program at NSF: "With new, improved full-waveform models; tools to lower the bar for community data access and analysis; and a supercomputing-powered platform to enable seismologists to discover the mysteries of the Earth's and other planetary deep interior, Bozdag is pushing the field into more precise, and open, territory."