Long known as a group of human relatives with big teeth and jaws, these ancient species lived for at least two million years alongside our ancestors.

21 JAN 2024 — JOHN HAWKS

Eye orbits of SK 48, Paranthropus robustus. Image: John Hawks

LONG READ

A time traveler who looked at the species of our ancient relatives around 1.5 million years ago would find that they belonged to two groups. One group included a handful of species that we call Homo. The other included two species with quite large molar and premolar teeth, and jawbones, faces, and jaw musculature to match. Most anthropologists today use the name Paranthropus for these big-jawed species of hominins.

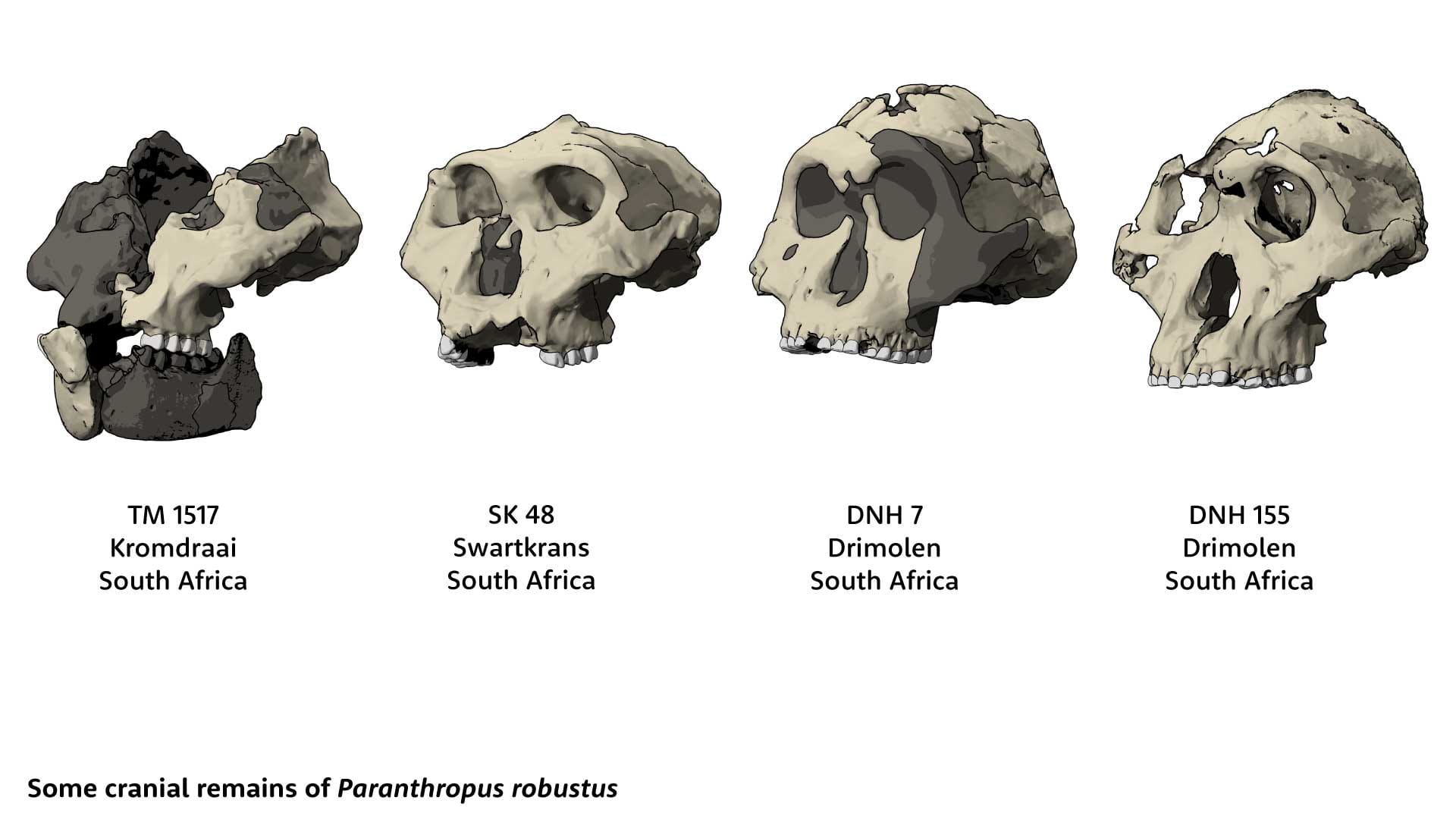

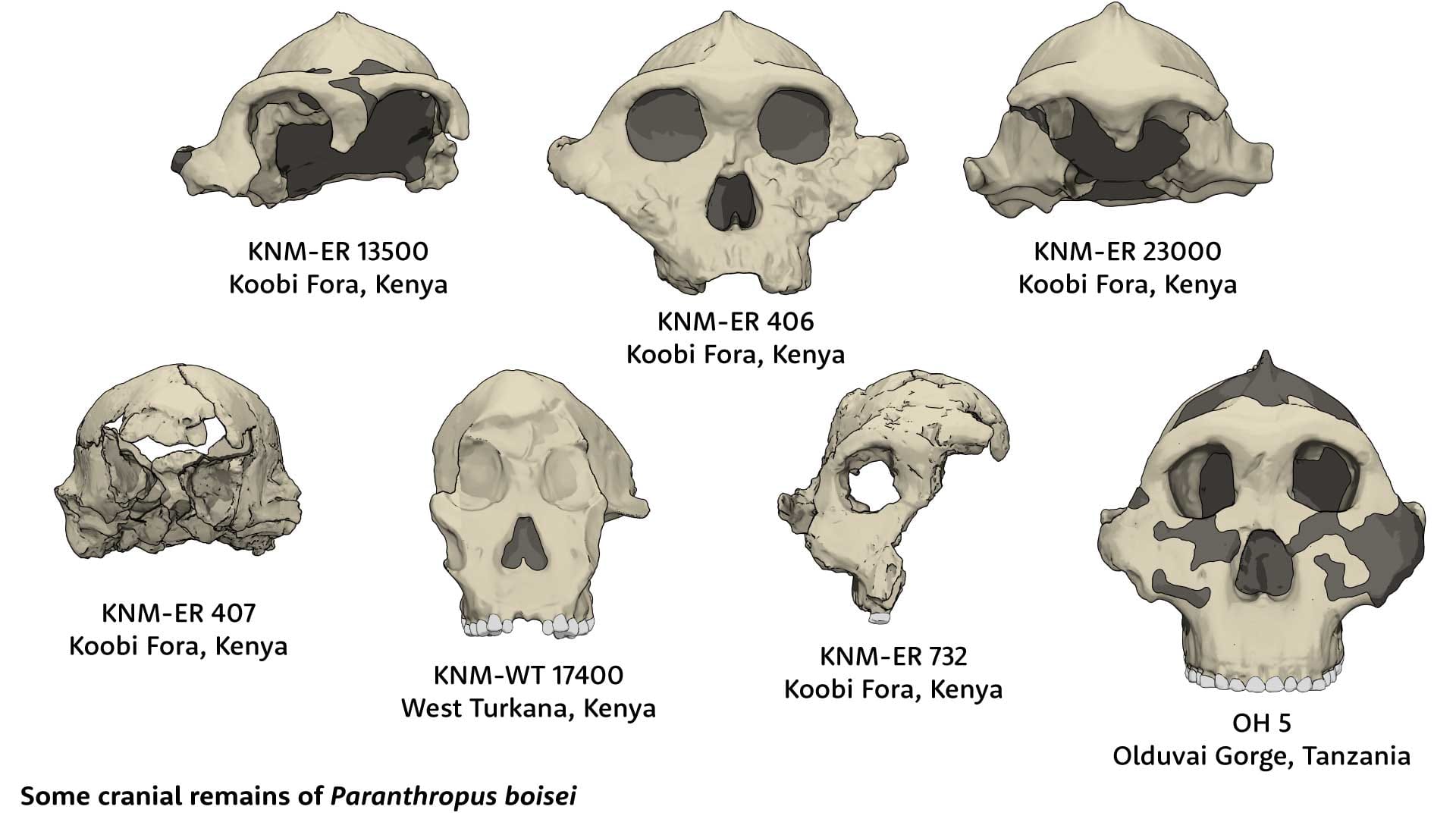

Fossils of Paranthropus are easy to recognize because of their distinctive skulls and teeth. They have large molars, premolars nearly as large as the molars, and small canines and incisors. Their mandibles are thick and tall. They have wide, massive cheekbones, wide zygomatic arches, and their cranial vaults often have raised sagittal and nuchal crests.

Such features give the appearance of strength, which led Robert Broom to give the name robustus to the species he first recognized at the South African site of Kromdraai in 1938. More than twenty years later, even larger jaws and teeth were found at Olduvai Gorge and other sites in eastern Africa. Anthropologists of the 1960s were in a phase of simplifying the number of names for genera and species, reducing all early hominins into Australopithecus. Even so, these fossils with big molars and jaws stood apart. Many scientists, following Phillip Tobias, began to call these forms “robust australopithecines”, a name that would be widely used for more than 40 years.

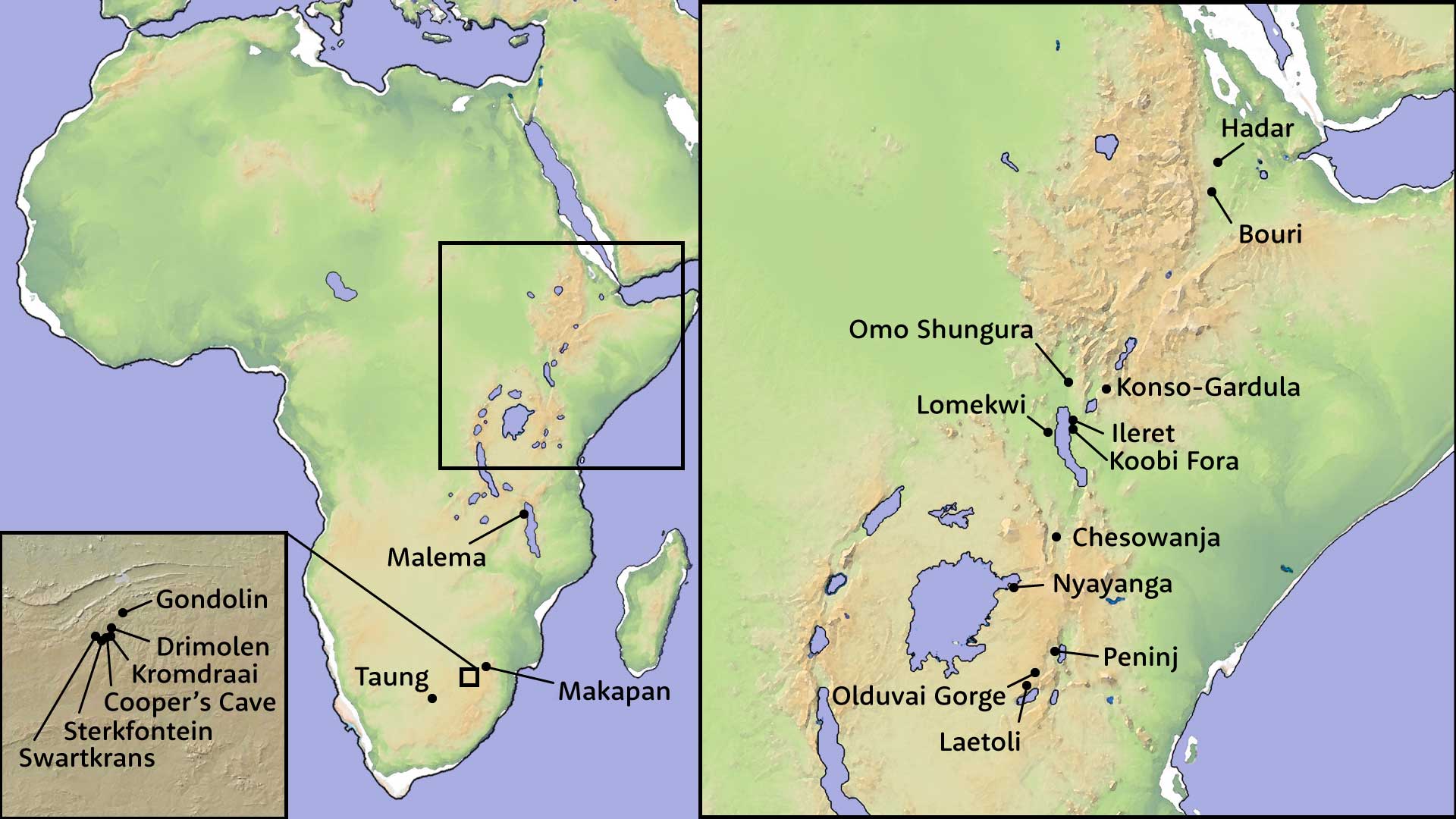

Today most scientists recognize three species of these large-jawed human relatives: Paranthropus robustus, Paranthropus boisei, and Paranthropus aethiopicus. Southern Africa was the home of P. robustus, while eastern Africa over time saw a succession of P. aethiopicus to P. boisei. Evidence shows that the lineage existed for around two million years, from around 3 million years ago until just under one million years ago. Hundreds of fossils of the three species are known to scientists today.

Map of sites with fossil evidence from Paranthropus, as well as some additional well-known fossil sites for context.

Paranthropus lived almost everywhere that earlier hominin species have been found. But there are exceptions. No fossils of Paranthropus have yet been found in the Afar region of northeastern Ethiopia. From 2.5 million to 1.2 million years ago when P. aethiopicus and P. boisei were the most abundant hominins in the Turkana Basin, only fossils of Homo and of Australopithecus garhi have been identified in the Afar region. This limitation to Paranthropus geographic range may help explain why this successful and numerous lineage has not yet been found in Eurasia.

Scientists long viewed these species as specialists with a different diet and lifestyle than other hominins. But evidence today suggests that Paranthropus behavior overlapped with early Homo in many ways, from tool use to food choices. Researchers are starting to ask new questions about how they interacted and how their evolution may have been connected with our own.

Paranthropus robustusFirst appearance: 2.3 million years, Kromdraai, South Africa

Last appearance: 1 million to 800,000 years ago, Swartkrans, South Africa

Holotype: TM 1517 partial skeleton, Kromdraai, South Africa

Named by: Robert Broom in a 1938 article.

Etymology: Paranthropus comes from Greek, meaning “near human”, and robustus is Latin for “firm” or “hard”.

Robert Broom related the story of how a young boy named Gert Terblanche discovered the first fossil of P. robustus from an outcrop of breccia near his family's farm. The place where this partial skeleton was found became known as the Kromdraai fossil site, and renewed scientific investigation of the site during the last twenty years has expanded the record of fossils and their context. This ancient cave is today only preserved as a remnant deposit of fossil breccia upon a hilltop, and is the site of some of the oldest-known fossils of P. robustus, up to 2.3 million years old.

Paranthropus lived almost everywhere that earlier hominin species have been found. But there are exceptions. No fossils of Paranthropus have yet been found in the Afar region of northeastern Ethiopia. From 2.5 million to 1.2 million years ago when P. aethiopicus and P. boisei were the most abundant hominins in the Turkana Basin, only fossils of Homo and of Australopithecus garhi have been identified in the Afar region. This limitation to Paranthropus geographic range may help explain why this successful and numerous lineage has not yet been found in Eurasia.

Scientists long viewed these species as specialists with a different diet and lifestyle than other hominins. But evidence today suggests that Paranthropus behavior overlapped with early Homo in many ways, from tool use to food choices. Researchers are starting to ask new questions about how they interacted and how their evolution may have been connected with our own.

Paranthropus robustusFirst appearance: 2.3 million years, Kromdraai, South Africa

Last appearance: 1 million to 800,000 years ago, Swartkrans, South Africa

Holotype: TM 1517 partial skeleton, Kromdraai, South Africa

Named by: Robert Broom in a 1938 article.

Etymology: Paranthropus comes from Greek, meaning “near human”, and robustus is Latin for “firm” or “hard”.

Robert Broom related the story of how a young boy named Gert Terblanche discovered the first fossil of P. robustus from an outcrop of breccia near his family's farm. The place where this partial skeleton was found became known as the Kromdraai fossil site, and renewed scientific investigation of the site during the last twenty years has expanded the record of fossils and their context. This ancient cave is today only preserved as a remnant deposit of fossil breccia upon a hilltop, and is the site of some of the oldest-known fossils of P. robustus, up to 2.3 million years old.

Most fossils of P. robustus come from just four ancient cave sites: Kromdraai, Swartkrans, Drimolen, and Cooper's. A handful of fossils from other sites are also part of the sample, all found within the area of caves northwest of Johannesburg, South Africa. The largest number of fossils come from Swartkrans, which has deposits with P. robustus extending across a million years or more. Paranthropus robustus is the most common species of fossil hominin represented in these sites, although researchers have found some Homo fossils at some of the same sites.

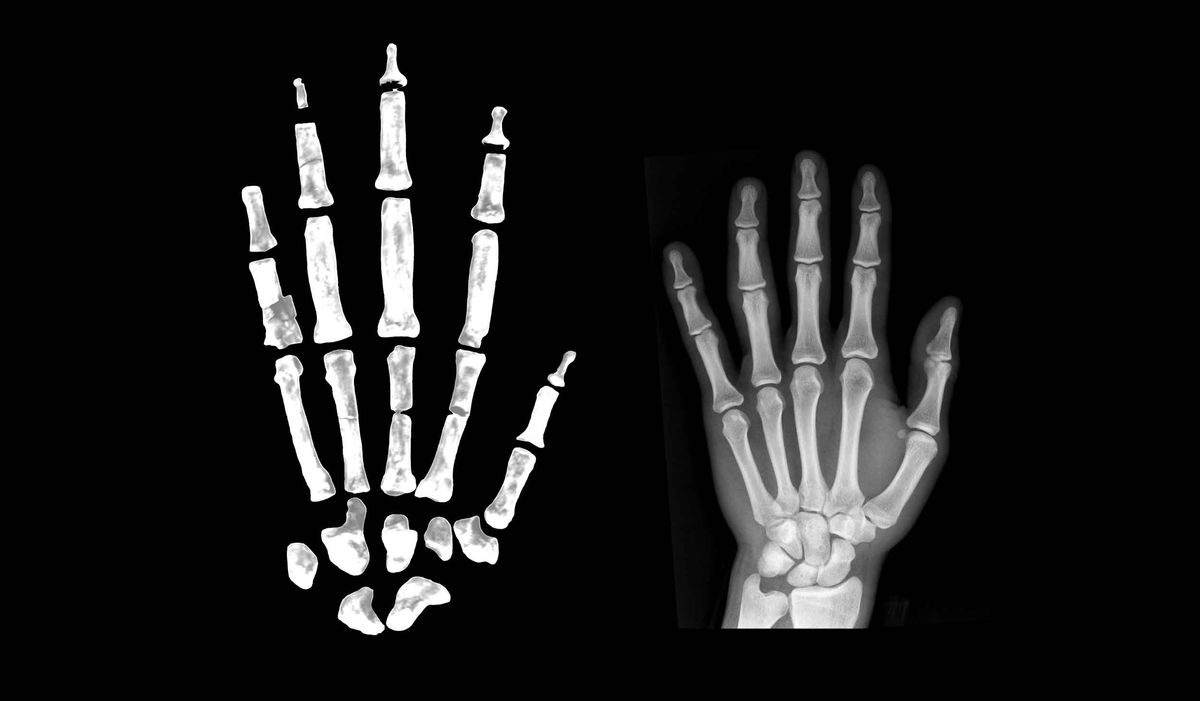

The postcranial record of P. robustus shows that this species had a body size similar to Australopithecus africanus, with an average body mass between 30 and 40 kilograms. The pelvis and femur of P. robustus also look like Australopithecus, with a wide pelvis relative to stature, long femoral neck, and strong bicondylar angle at the knee. The form of the humerus shows strength for rotating and flexing the forearm, which may suggest that the species relied on climbing as earlier hominins had done. The Swartkrans sample of P. robustus includes many fossil hand bones, which show that this species could use its hands to make and use tools. Many stone and bone tools have been found at the sites that preserve P. robustus fossils.

Paranthropus boiseiFirst appearance: 2.5 to 2.3 million years, Malema, Malawi

Last appearance: 1.34 million years ago, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania

Holotype: OH 5 cranium, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania

Named by: Louis Leakey in a 1959 article named the OH 5 fossil Zinjanthropus boisei. John Robinson was the first to suggest attributing the species to Paranthropus.

Etymology: Zinj, more usually spelled Zanj, is a word from Arabic referring to eastern Africa, anthropos is the Greek word for “human”, and boisei was named for Charles Boise, who provided funding for some of the fieldwork by Louis and Mary Leakey.

Paranthropus boisei is one of the best known fossil hominin species. Compared to all other hominin species, P. boisei has the largest and thickest mandibles and biggest molar teeth. Mary and Louis Leakey found the first large molar in their work at Olduvai Gorge in 1955, followed in 1959 by the discovery of the OH 5 skull. Other discoveries at Olduvai Gorge would follow over the years, including the OH 80 specimen, a case in which teeth were recovered together with a few parts of the postcranial skeleton.

Most of the known sample of P. boisei comes from the Turkana Basin. Many of the major discoveries of this species were made by specialists working with Richard and Maeve Leakey, who started fieldwork at Koobi Fora and Ileret in 1968. The species is the most common hominin in the fossil deposits of the Turkana Basin from around 2.3 million to 1.5 million years ago.

The overall picture of P. boisei body size and postcranial anatomy is less well known than for P. robustus. Postcranial fossil fragments from the East African Rift System sites usually cannot be attributed to species unless researchers find them with teeth or identifiable cranial fragments. But in recent years, researchers have made progress on understanding P. boisei body size and anatomy through some new discoveries of partial P. boisei skeletons and comparative study of P. robustus fossils. One partial skeleton from Koobi Fora, KNM-ER 1500, comes from an individual that was similar in size to the small “Lucy” skeleton of Australopithecus afarensis, around 30 kilograms, while the OH 80 partial skeleton represents a larger individual of 45 to 50 kilograms. Paranthropus boisei had strong arms, with large muscle attachments on the humerus and a highly curved ulna shaft. As in the case of P. robustus, this may mean that climbing was important in the behavioral pattern of P. boisei. Tool use was also important to this species, with finger and hand bones showing the same potential as in P. robustus.

Paranthropus aethiopicusFirst appearance: 2.8 to 2.5 million years, Shungura Formation, Omo Valley, Ethiopia

Last appearance: 2.3 to 2.1 million years ago, Shungura Formation, Omo Valley, Ethiopia

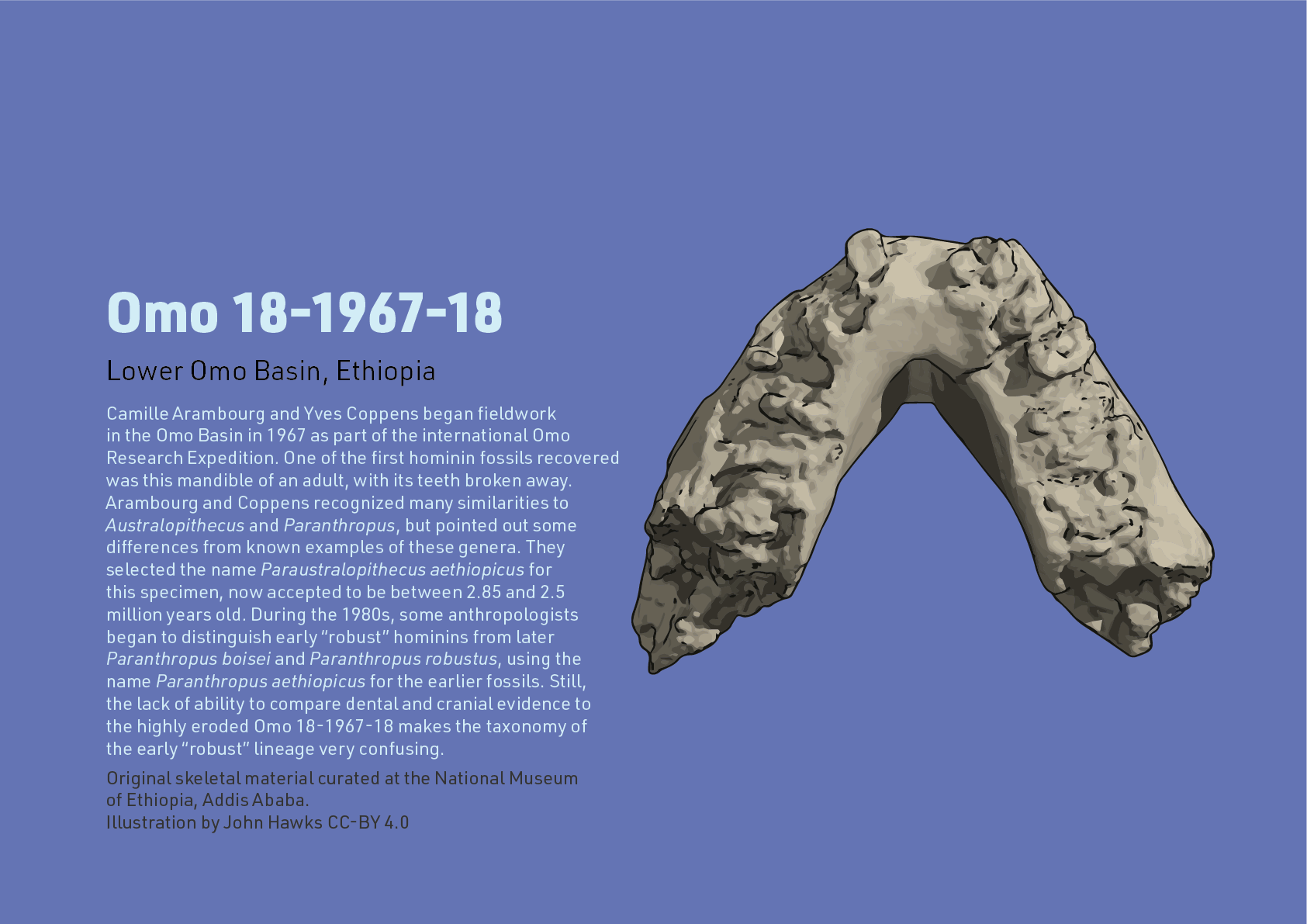

Holotype: Omo 18-1967-18 partial mandible, Shungura Formation, Omo Valley, Ethiopia

Named by: Camille Arambourg and Yves Coppens in a brief 1967 note named this fossil Paraustralopithecus aethiopicus, providing a diagnosis in a second article in 1968. Other researchers later referred the species to Australopithecus, and then to Paranthropus, as ideas about the relationships and rank of these hominins changed over time.

Etymology: Paraustralopithecus comes from Greek, meaning “near Australopithecus”, and aethiopicus refers to Ethiopia.

The French team working as part of the 1967 International Palaeontological Research Expedition to the Omo River found a hominin mandible from an area they designated Omo 18. As they described the jaw, Camille Arambourg and Yves Coppens claimed it was different from any other hominin known at that time. Still, the fossil preserves only the body of the mandible and tooth roots, without any of the tooth crowns. This makes it challenging to evaluate whether other fossils discovered since 1967 may belong to the same species.

Fact sheet for the Omo 18-1967-18 mandible.

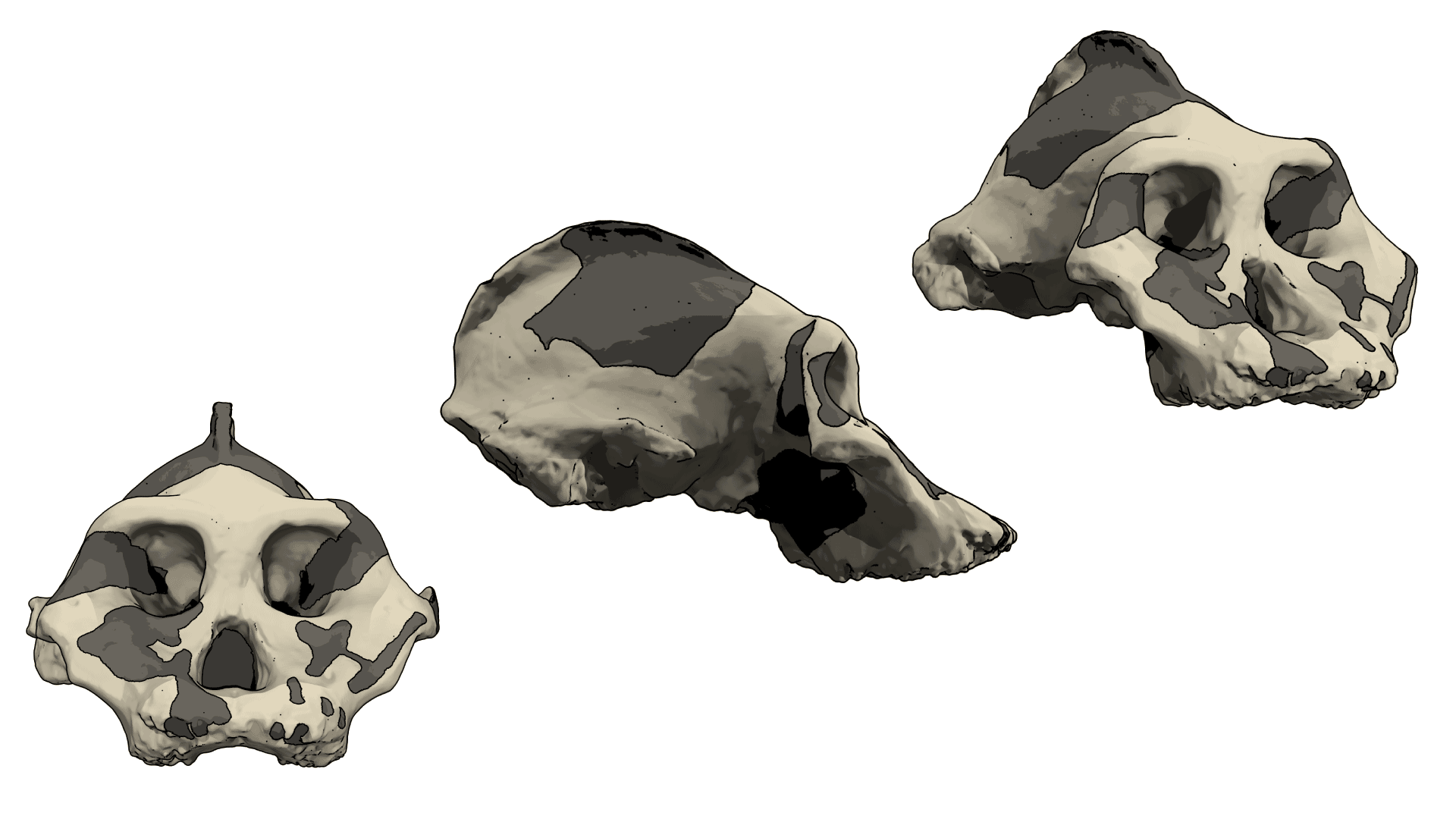

The name aethiopicus might have been forgotten were it not for the discovery in 1985 of a skull from the Lomekwi area of the western Turkana Basin. The KNM-WT 17000 skull, known as the “Black Skull” for its dark manganese oxide staining, came from an individual that lived around 2.5 million years ago. The skull has no tooth crowns remaining. But the large remaining tooth roots make clear that its molars and premolars were similar in size to P. boisei. The large sagittal and nuchal crests also fit what is seen in the later species. But other aspects of the skull look different from P. boisei, including its sloping and prognathic face, relatively small brain size, and shape of the joint that connects the skull and mandible.

Alan Walker and Richard Leakey, who described the KNM-WT 17000 skull, attributed it to Australopithecus boisei. At least one scientist thought the skull deserved its own species name, naming it Australopithecus walkeri. But the fossil record was a bit more extensive than these two specimens.Walker and Leakey had also described a jawbone from Kangatukuseo, near Lomekwi, which seemed similar in shape and size to Omo 18-1967-18. Between this time and 1.9 million years ago, when Paranthropus boisei is well-represented at Ileret and Koobi Fora, only fragmentary fossils from the Shungura Formation are known. Researchers who studied those fossils during the late 1980s and 1990s, led by Gen Suwa, recognized that the “robust” lineage had changed over time. Molars and premolars became larger, and some aspects of tooth shape evolved to be more boisei-like over time. The earlier fossils, in their view, were something different.

The name aethiopicus might have been forgotten were it not for the discovery in 1985 of a skull from the Lomekwi area of the western Turkana Basin. The KNM-WT 17000 skull, known as the “Black Skull” for its dark manganese oxide staining, came from an individual that lived around 2.5 million years ago. The skull has no tooth crowns remaining. But the large remaining tooth roots make clear that its molars and premolars were similar in size to P. boisei. The large sagittal and nuchal crests also fit what is seen in the later species. But other aspects of the skull look different from P. boisei, including its sloping and prognathic face, relatively small brain size, and shape of the joint that connects the skull and mandible.

Alan Walker and Richard Leakey, who described the KNM-WT 17000 skull, attributed it to Australopithecus boisei. At least one scientist thought the skull deserved its own species name, naming it Australopithecus walkeri. But the fossil record was a bit more extensive than these two specimens.Walker and Leakey had also described a jawbone from Kangatukuseo, near Lomekwi, which seemed similar in shape and size to Omo 18-1967-18. Between this time and 1.9 million years ago, when Paranthropus boisei is well-represented at Ileret and Koobi Fora, only fragmentary fossils from the Shungura Formation are known. Researchers who studied those fossils during the late 1980s and 1990s, led by Gen Suwa, recognized that the “robust” lineage had changed over time. Molars and premolars became larger, and some aspects of tooth shape evolved to be more boisei-like over time. The earlier fossils, in their view, were something different.

The “Black Skull”, KNM-WT 17000, from Lomekwi, Kenya.

These researchers and others of the late 1980s recognized the earlier part of the “robust” lineage in the Turkana Basin as Australopithecus aethiopicus. This is where things still stand today, except that many researchers separate the “robust” species into Paranthropus. But the fossil record does not make clear exactly when and where the boundary between P. aethiopicus and P. boisei may have existed, or whether there was any distinct boundary at all.

Jaws and molars

Early scientists who studied these species had some strong ideas about their large jaw muscles and molars. When Louis Leakey saw the OH 5 fossil, he came up with the name “Nutcracker Man” to describe what he saw as a powerful bite. During the 1950s, John Robinson described many of the P. robustus fossils from Swartkrans as well as Au. africanus from Sterkfontein. He came to the idea that the differences between these species were a result of their diets. In his view, the large molars and jaws of Paranthropus marked them as vegetarians, while the more generalized teeth of Australopithecus pointed to a more omnivorous diet. In his view, the vegetarian lifestyle meant that P. robustus did not make the stone tools that were found with the species at Swartkrans.

These researchers and others of the late 1980s recognized the earlier part of the “robust” lineage in the Turkana Basin as Australopithecus aethiopicus. This is where things still stand today, except that many researchers separate the “robust” species into Paranthropus. But the fossil record does not make clear exactly when and where the boundary between P. aethiopicus and P. boisei may have existed, or whether there was any distinct boundary at all.

Jaws and molars

Early scientists who studied these species had some strong ideas about their large jaw muscles and molars. When Louis Leakey saw the OH 5 fossil, he came up with the name “Nutcracker Man” to describe what he saw as a powerful bite. During the 1950s, John Robinson described many of the P. robustus fossils from Swartkrans as well as Au. africanus from Sterkfontein. He came to the idea that the differences between these species were a result of their diets. In his view, the large molars and jaws of Paranthropus marked them as vegetarians, while the more generalized teeth of Australopithecus pointed to a more omnivorous diet. In his view, the vegetarian lifestyle meant that P. robustus did not make the stone tools that were found with the species at Swartkrans.

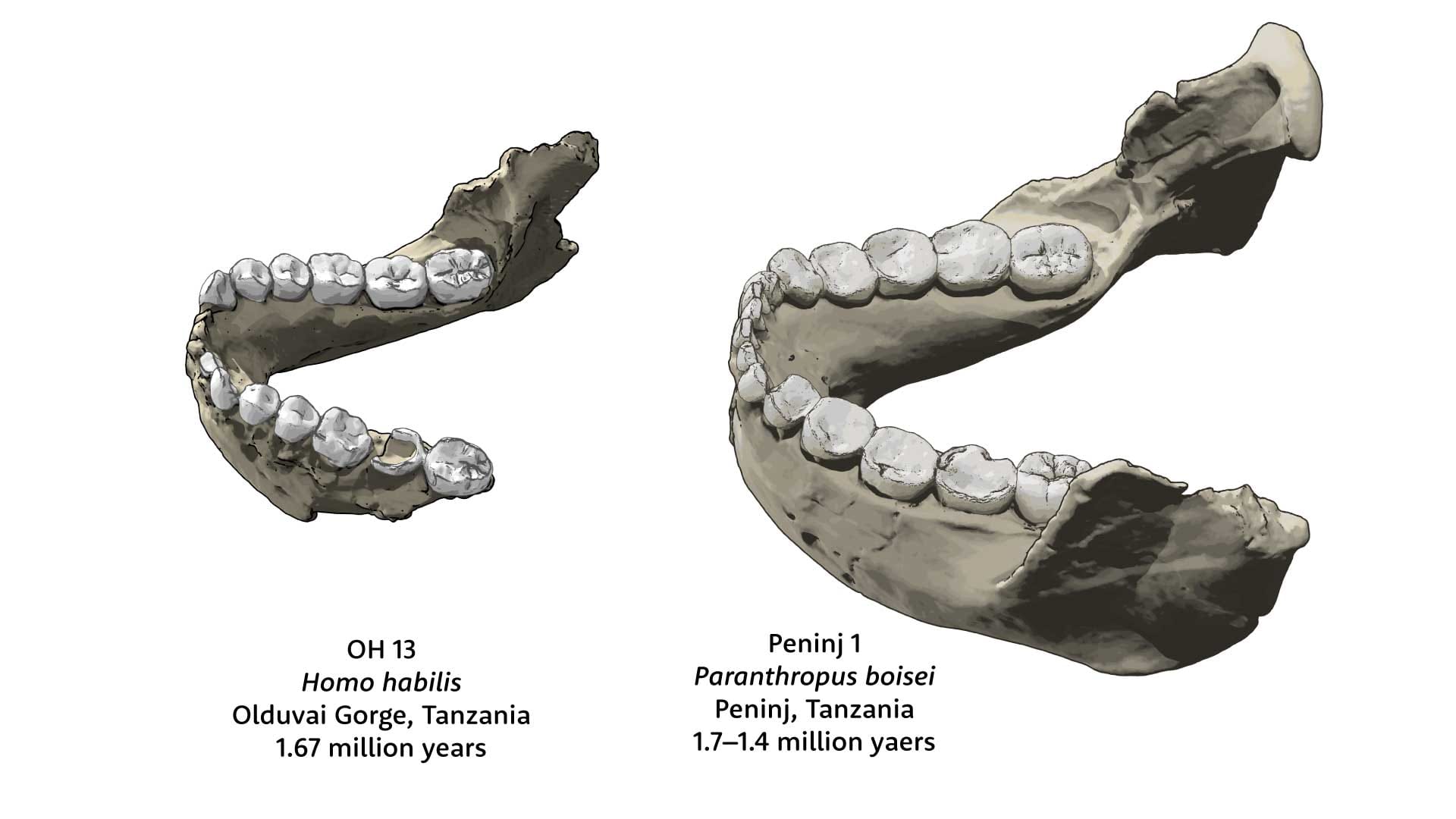

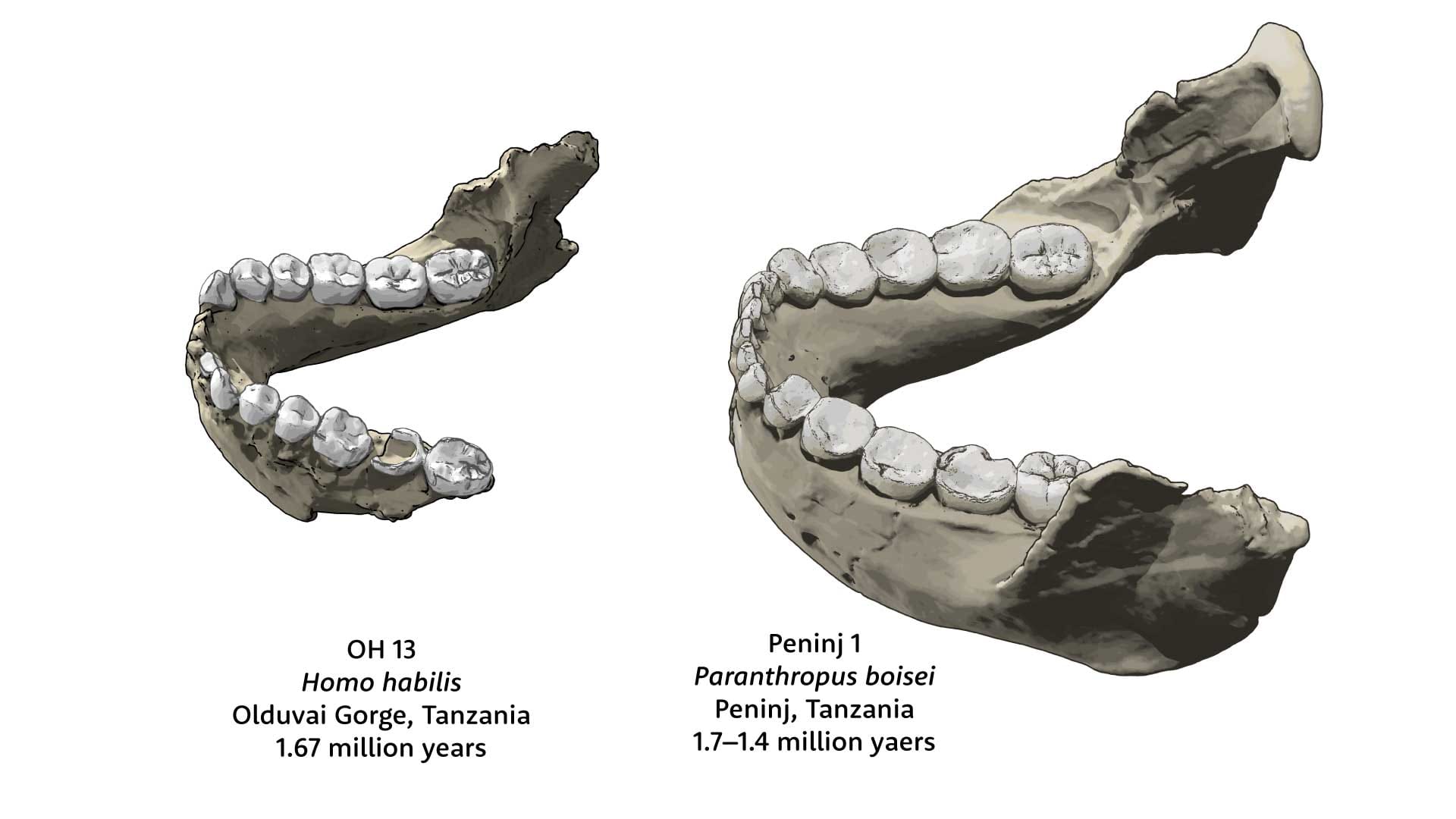

Two species that lived at the same time in the East African Rift System are Homo habilis and Paranthropus boisei. Their jaws and teeth were very different in size and morphology.

Today anthropologists know much more about how Paranthropus species used their teeth. Engineering models show that the faces and jaws of these species were indeed capable of exerting and withstanding great force. At the same time, their big, flat molars were less efficient at transmitting strong force to the foods that they ate. Michael Berthaume and Kornelius Kupczik suggested one possible explanation: strong jaws may have compensated for big teeth, which were themselves more useful for resisting wear than biting down on hard foods.

Sharing big teeth and jaws did not make Paranthropus all eat alike. Foods leave microscopic scratches and pits upon the surfaces of teeth, and the markings on Paranthropus boisei teeth show that they chewed on tough foods like leaves and stems, rather than hard foods like nuts and seeds. They seem to have used their big jaw muscles like cows or gorillas, sometimes chewing for hours each day. On the other hand, P. robustus teeth show a more diverse array of scratches and pits, suggesting that they had a varied diet. For that species, being able to undertake long bouts of chewing may enabled flexibility of food choices. That impression is confirmed by studies of the isotopes of carbon and calcium in the tooth enamel. The diet of almost all P. boisei individuals was strongly focused toward foods with carbon derived from warm-season grasses. Paranthropus robustus and P. aethiopicus consumed foods from a wider array of sources, very much like Australopithecus africanus and early species of Homo. All of these species were using stone tools, and in South Africa P. robustus used bone tools, possibly for insect foraging.

Today anthropologists know much more about how Paranthropus species used their teeth. Engineering models show that the faces and jaws of these species were indeed capable of exerting and withstanding great force. At the same time, their big, flat molars were less efficient at transmitting strong force to the foods that they ate. Michael Berthaume and Kornelius Kupczik suggested one possible explanation: strong jaws may have compensated for big teeth, which were themselves more useful for resisting wear than biting down on hard foods.

Sharing big teeth and jaws did not make Paranthropus all eat alike. Foods leave microscopic scratches and pits upon the surfaces of teeth, and the markings on Paranthropus boisei teeth show that they chewed on tough foods like leaves and stems, rather than hard foods like nuts and seeds. They seem to have used their big jaw muscles like cows or gorillas, sometimes chewing for hours each day. On the other hand, P. robustus teeth show a more diverse array of scratches and pits, suggesting that they had a varied diet. For that species, being able to undertake long bouts of chewing may enabled flexibility of food choices. That impression is confirmed by studies of the isotopes of carbon and calcium in the tooth enamel. The diet of almost all P. boisei individuals was strongly focused toward foods with carbon derived from warm-season grasses. Paranthropus robustus and P. aethiopicus consumed foods from a wider array of sources, very much like Australopithecus africanus and early species of Homo. All of these species were using stone tools, and in South Africa P. robustus used bone tools, possibly for insect foraging.

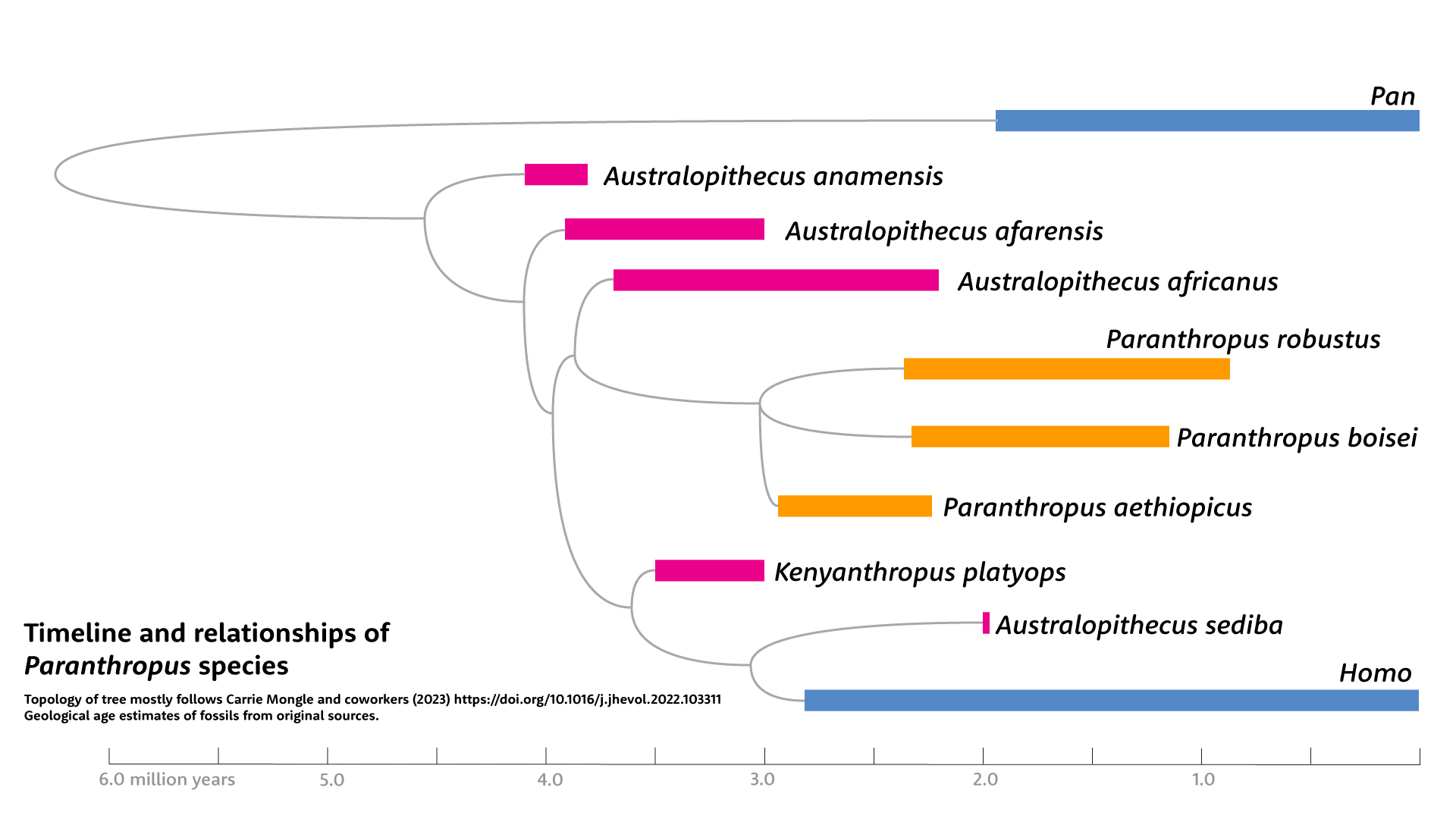

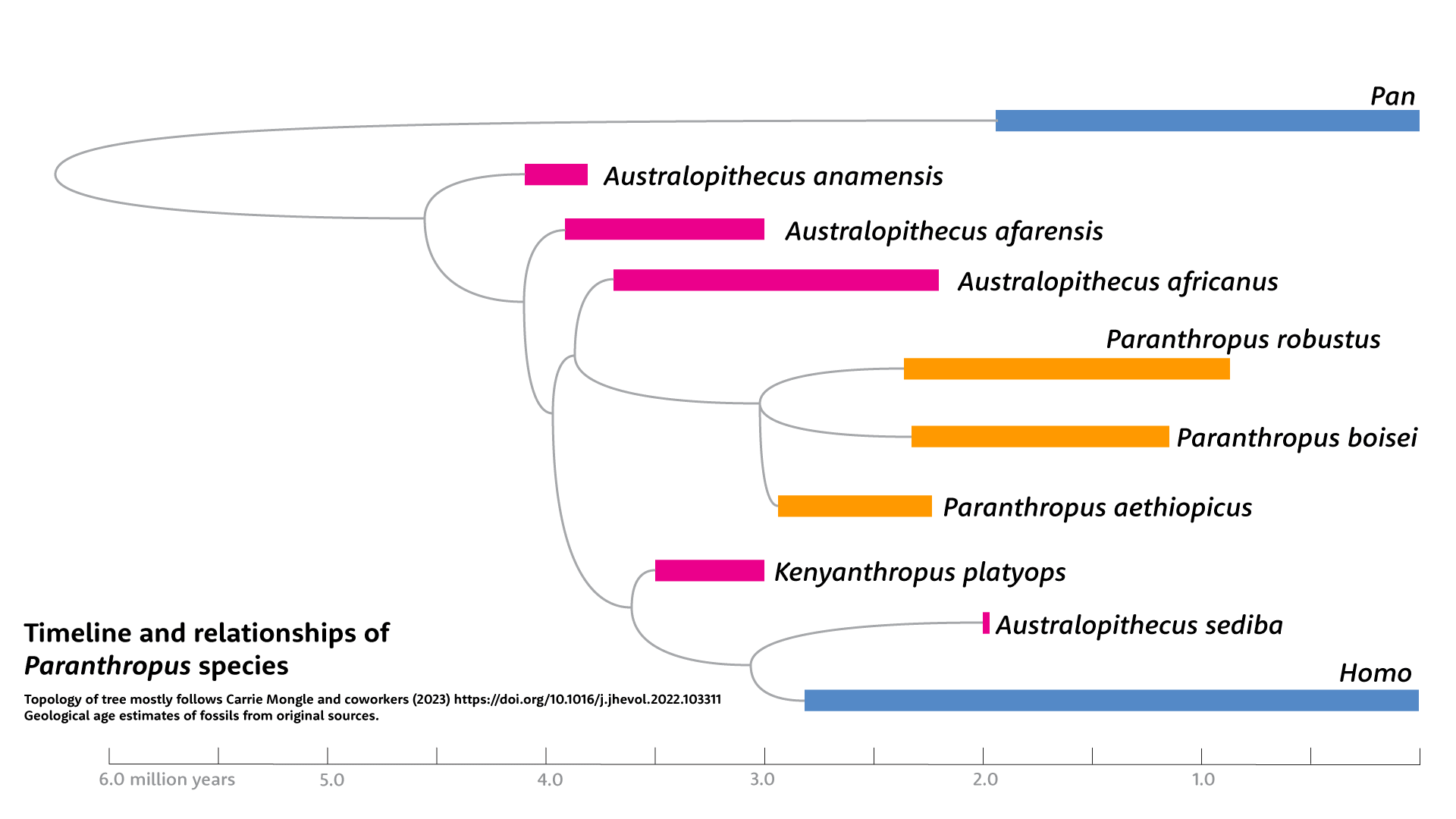

Relationships of Paranthropus species

Most scientists accept that the three species P. boisei, P. aethiopicus, and P. robustus are close relatives of each other. This close relationship is supported by many similarities in their jaws, teeth and skulls. No other hominins have the expanded molar dimensions and thickened enamel that these species share, nor do any other hominins have premolars that have evolved toward a molar-like shape in the same way. Such are derived or apomorphic in the three species of Paranthropus.

Of course these species also have some differences from each other. The strongly sloped face profile of the KNM-WT 17000 skull resembles earlier hominins like Au. afarensis more than it does the later P. boisei skulls, for example. But this kind of plesiomorphic similarity does not provide evidence of a close relationship, because it is also shared with other, more distantly related species. In this case, it's the vertical face orientation shared by P. robustus and P. boisei that is the derived trait, different from the relatives of both species. This may reflect a close relationship between these two species compared to the earlier P. aethiopicus. From comparisons like these anthropologists build their understanding of the phylogenetic tree.

Considering the shared derived traits of P. robustus and P. boisei, many researchers accept them as sister species. The record of Paranthropus fossils before 2.3 million years ago is harder to assess, but fossils like KNM-WT 17000 and Omo 18-1967-18 do not share all the derived traits of later Paranthropus. Some researchers think that P. aethiopicus was the common ancestor of P. robustus and P. boisei. In this scenario, the adaptation to powerful chewing first arose sometime before 3 million years ago in an early population of big-jawed hominins that became P. aethiopicus. Around 2.3 million years ago, the populations in the East African Rift System evolved the derived set of features found in P. boisei. The fossil record does not make clear when Paranthropus first reached southern Africa, but the lack of some P. boisei features in P. robustus suggests that the two species diverged before 2.3 million years ago.

Yet there has always been some doubt about whether jaws tell the whole story. The features that link the three “robust” species are almost all connected with a single function: heavy chewing. Individuals with thick jawbones also tend to have tall jawbones and larger jaw muscles. Scientists may choose to count those as separate traits, but they all evolve in concert with each other. Their correlation makes these traits weaker evidence of relationship than they might seem. Anthropologists cannot easily look beyond the jaws, teeth, and bones of the skull—such elements are, after all, most of the fossil record.

Over the years some anthropologists have suggested that maybe the South African P. robustus may actually have evolved from Au. africanus or some other ancestor within southern Africa. If that idea were correct, then the South African P. robustus may have evolved its large jaw musculature, large molars, and large molar-shaped premolars in parallel with the East African P. aethiopicus—P. boisei lineage. Some of the Australopithecus fossils from Sterkfontein and Makapansgat do have very large molars and jaws that overlap with P. robustus in their size and thickness. These traits are among the reasons why Au. africanus is placed as a sister branch to the three Paranthropus species in most analyses of hominin phylogeny. Still, over the last forty years most analyses have supported the idea that the similarities of P. robustus and P. boisei was unlikely to have been a result of parallel evolution.

Paranthropus extinction

The earliest fossils attributed to Paranthropus are two teeth from Nyayanga, Kenya, where they come from sediments between 3 million and 2.6 million years old. With only two teeth, there's not enough information to know for certain if these teeth are P. aethiopicus or potentially yet another, earlier, species. This site near Lake Victoria is also the earliest known archaeological site with Oldowan stone tools, which suggests that the large-toothed Paranthropus existed in a technological world from its very beginning.

So when Homo first arose, Paranthropus was our senior partner. Both P. robustus and P. boisei were long-lived species, each originating by 2.3 million years ago and becoming extinct more than a million years later. African climates and environments changed a great deal during that long period of time. Paranthropus found ways to thrive, its fossils more common than those of other species that lived at the same time, including every kind of early Homo. It's a mystery why this successful lineage became extinct.

There is no satisfying answer, but there are clues. Paranthropus coexisted comfortably with several varieties of Homo, including one of the most well-known hominin species of all, Homo erectus. In Africa, Homo erectus has been found in sites from nearly two million years ago up to a little under one million. It was a cosmopolitan species, with both early and late sites at the extreme ends of the continent. And of course, H. erectus spread out into Asia shortly after it first evolved, becoming the first transcontinental hominin species. Whatever Homo erectus had, it was not enough to extinguish P. robustus or P. boisei. Still, each of the big-toothed species was limited to its region, with little sign that there was much gene flow between them. Possibly the most surprising fact is that P. boisei never seems to have been successful in the Afar region of Ethiopia, where so many other fossil hominins have been found. The trade-off between behavioral flexibility and tailoring to specific ecological surroundings is one that most species face. Maybe later Paranthropus populations oriented themselves less toward dispersal and more toward fitting in where they already lived.

While H. erectus kept going strong in Asia after one million years ago, in Africa things were changing. Humanlike species diversified further. One form would become the ancestors of H. naledi. Another was a new species with a larger brain than H. erectus. Populations of this human species, already separating genetically by one million years ago, would eventually merge to become the global Homo sapiens. This dawning Middle Pleistocene world was the one that gave rise to us. Whether a place for Paranthropus long remained in this world no one can yet say.

Still, it's likely that we are missing the whole picture. Their reputation as a hominin side-branch has distracted some scientists from the anatomical reality that Paranthropus shares a whole lot with our closer relatives. To be sure, the molars and premolars of P. boisei are very large and different in shape from early species of Homo. But P. robustus did not always fit this stereotype. That species overlapped greatly with Australopithecus africanus and early species of Homo in molar and premolar sizes. Some recent research suggests that some fossils long classified as early members of Homo were actually Paranthropus instead. A smaller-toothed population of Paranthropus might well be hiding in our fragmented fossil record.

Maybe the reason why the more extreme Paranthropus species ultimately became extinct is because earlier populations sometimes mixed with—or even evolved into—more humanlike species. If so, this divergent group may have been one earlier channel of the braided stream. Widening the window of sites in southern Africa will be central to solving this evolutionary mystery.

Notes: The recent work pointing to small Paranthropus teeth that may have been wrongly attributed to Homo is on the enamel-dentin junction of South African hominins by Clément Zanolli and coworkers (2022). I've expanded on this in a previous post: “Secrets within the teeth of the first Homo fossils.”

Active debate over the relationships of Paranthropus occupied much of the late 1980s into the 2000s, with researchers gathering more and more data to understand whether the various species are close relatives. Although this has quieted down since, some researchers still favor a hypothesis in which southern African Australopithecus gave rise to P. robustus, or possibly to all Paranthropus species.

Readers interested in the dietary evidence should check out a recent review by Matt Sponheimer and coworkers, titled “Problems with Paranthropus”. I discussed evidence of tool use by Paranthropus species at length in my post, “All the hominins made tools”. There are many ins and outs of the association of postcranial evidence with Paranthropus, especially in the Turkana Basin, and the recent paper by Carol Ward and coworkers attributing KNM-ER 1500 to P. boisei is a good introduction to that topic.

Guide to Sahelanthropus, Orrorin and Ardipithecus

These fossil species between 8 million and 4.4 million years old include some of the earliest members of the hominin lineage.

References

Arambourg, C., & Coppens, Y. (1967). Sur la découverte, dans le Pléistocène inférieur de la vallée de l’Omo (Éthiopie), d’une mandibule d’australopithécien. Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires Des Seances De l’Academie Des Sciences. Serie D: Sciences Naturelles, 265(8), 589–590.

Berthaume, M. A., & Kupczik, K. (2021). Molar biomechanical function in South African hominins Australopithecus africanus and Paranthropus robustus. Interface Focus, 11(5), 20200085. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2020.0085

Braga, J., Chinamatira, G., Zipfel, B., & Zimmer, V. (2022). New fossils from Kromdraai and Drimolen, South Africa, and their distinctiveness among Paranthropus robustus. Scientific Reports, 12(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18223-7

Leakey, R. E. F., & Walker, A. (1988). New Australopithecus boisei specimens from east and west Lake Turkana, Kenya. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 76(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330760102

Martin, J. M., Leece, A. B., Neubauer, S., Baker, S. E., Mongle, C. S., Boschian, G., Schwartz, G. T., Smith, A. L., Ledogar, J. A., Strait, D. S., & Herries, A. I. R. (2021). Drimolen cranium DNH 155 documents microevolution in an early hominin species. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-01319-6

Mongle, C. S., Strait, D. S., & Grine, F. E. (2023). An updated analysis of hominin phylogeny with an emphasis on re-evaluating the phylogenetic relationships of Australopithecus sediba. Journal of Human Evolution, 175, 103311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2022.103311

Smith, A. L., Benazzi, S., Ledogar, J. A., Tamvada, K., Pryor Smith, L. C., Weber, G. W., Spencer, M. A., Lucas, P. W., Michael, S., Shekeban, A., Al-Fadhalah, K., Almusallam, A. S., Dechow, P. C., Grosse, I. R., Ross, C. F., Madden, R. H., Richmond, B. G., Wright, B. W., Wang, Q., … Strait, D. S. (2015). The Feeding Biomechanics and Dietary Ecology of Paranthropus boisei. The Anatomical Record, 298(1), 145–167. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.23073

Sponheimer, M., Daegling, D. J., Ungar, P. S., Bobe, R., & Paine, O. C. C. (2023). Problems with Paranthropus. Quaternary International, 650, 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2022.03.024

Susman, R. L. (1988). Hand of Paranthropus robustus from Member 1, Swartkrans: Fossil Evidence for Tool Behavior. Science, 240(4853), 781–784. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3129783

Susman, R. L. (1991). Who Made the Oldowan Tools? Fossil Evidence for Tool Behavior in Plio-Pleistocene Hominids. Journal of Anthropological Research, 47(2), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1086/jar.47.2.3630322

Ward, C. V., Hammond, A. S., Grine, F. E., Mongle, C. S., Lawrence, J., & Kimbel, W. H. (2023). Taxonomic attribution of the KNM-ER 1500 partial skeleton from the Burgi Member of the Koobi Fora Formation, Kenya. Journal of Human Evolution, 184, 103426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2023.103426

Paranthropus robustusParanthropus boiseiParanthropus aethiopicusexplainertechnologyEarly Stone AgeextinctionShare on Twitter

Share on Facebook

Share on LinkedIn

Share on Pinterest

Share via Email

Copy link

John Hawks Twitter

I'm a paleoanthropologist exploring the world of ancient humans and our fossil relatives.

These fossil species between 8 million and 4.4 million years old include some of the earliest members of the hominin lineage.

References

Arambourg, C., & Coppens, Y. (1967). Sur la découverte, dans le Pléistocène inférieur de la vallée de l’Omo (Éthiopie), d’une mandibule d’australopithécien. Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires Des Seances De l’Academie Des Sciences. Serie D: Sciences Naturelles, 265(8), 589–590.

Berthaume, M. A., & Kupczik, K. (2021). Molar biomechanical function in South African hominins Australopithecus africanus and Paranthropus robustus. Interface Focus, 11(5), 20200085. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2020.0085

Braga, J., Chinamatira, G., Zipfel, B., & Zimmer, V. (2022). New fossils from Kromdraai and Drimolen, South Africa, and their distinctiveness among Paranthropus robustus. Scientific Reports, 12(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18223-7

Leakey, R. E. F., & Walker, A. (1988). New Australopithecus boisei specimens from east and west Lake Turkana, Kenya. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 76(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330760102

Martin, J. M., Leece, A. B., Neubauer, S., Baker, S. E., Mongle, C. S., Boschian, G., Schwartz, G. T., Smith, A. L., Ledogar, J. A., Strait, D. S., & Herries, A. I. R. (2021). Drimolen cranium DNH 155 documents microevolution in an early hominin species. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-01319-6

Mongle, C. S., Strait, D. S., & Grine, F. E. (2023). An updated analysis of hominin phylogeny with an emphasis on re-evaluating the phylogenetic relationships of Australopithecus sediba. Journal of Human Evolution, 175, 103311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2022.103311

Smith, A. L., Benazzi, S., Ledogar, J. A., Tamvada, K., Pryor Smith, L. C., Weber, G. W., Spencer, M. A., Lucas, P. W., Michael, S., Shekeban, A., Al-Fadhalah, K., Almusallam, A. S., Dechow, P. C., Grosse, I. R., Ross, C. F., Madden, R. H., Richmond, B. G., Wright, B. W., Wang, Q., … Strait, D. S. (2015). The Feeding Biomechanics and Dietary Ecology of Paranthropus boisei. The Anatomical Record, 298(1), 145–167. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.23073

Sponheimer, M., Daegling, D. J., Ungar, P. S., Bobe, R., & Paine, O. C. C. (2023). Problems with Paranthropus. Quaternary International, 650, 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2022.03.024

Susman, R. L. (1988). Hand of Paranthropus robustus from Member 1, Swartkrans: Fossil Evidence for Tool Behavior. Science, 240(4853), 781–784. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3129783

Susman, R. L. (1991). Who Made the Oldowan Tools? Fossil Evidence for Tool Behavior in Plio-Pleistocene Hominids. Journal of Anthropological Research, 47(2), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1086/jar.47.2.3630322

Ward, C. V., Hammond, A. S., Grine, F. E., Mongle, C. S., Lawrence, J., & Kimbel, W. H. (2023). Taxonomic attribution of the KNM-ER 1500 partial skeleton from the Burgi Member of the Koobi Fora Formation, Kenya. Journal of Human Evolution, 184, 103426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2023.103426

Paranthropus robustusParanthropus boiseiParanthropus aethiopicusexplainertechnologyEarly Stone AgeextinctionShare on Twitter

Share on Facebook

Share on LinkedIn

Share on Pinterest

Share via Email

Copy link

John Hawks Twitter

I'm a paleoanthropologist exploring the world of ancient humans and our fossil relatives.