Oldest known sex chromosome emerged 248 million years ago in an octopus ancestor

The oldest-known sex chromosome emerged in octopus and squid between 455 million and 248 million years ago — 180 million years earlier than the previous record-holder, scientists have discovered.

The oldest known sex chromosome in animals has been discovered, pushing back the date for the evolution of sex chromosomes to between 248 million and 455 million years ago.

The ancient chromosome was found in octopus and squid, suggesting that these may have been among the first animals to determine their sex via genetic blueprint, instead of environmental cues.

Sex chromosomes are standard in mammals. In humans, the sex chromosomes are X and Y. Males usually have an X and a Y chromosome, while females have two Xs, although there are some variations, such as XXX or XXY, which can have a wide range of impacts from no effect at all to certain learning disabilities or neurological differences.

For a long time, researchers weren't sure whether cephalopods, the soft-bodied mollusks that include squid and octopuses, determined their sex with chromosomes. Mollusks have a variety of ways to handle reproduction, including hermaphroditism or sequential hermaphroditism, in which individuals swap sexes over time.

Octopuses stick to one sex, but it wasn't clear whether genes or environmental cues determined what sex that would be. In some reptiles and fish, factors like temperature decide the sex of offspring.

Related: Octopuses torture and eat themselves after mating. Science finally knows why.

In 2015, researchers completed the first full gene sequence of a cephalopod, the California two-spot octopus (Octopus bimaculoides). That sequence still included gaps, though, so a team led by Andrew Kern, a biologist at the University of Oregon, set about filling them in with high-fidelity sequencing.

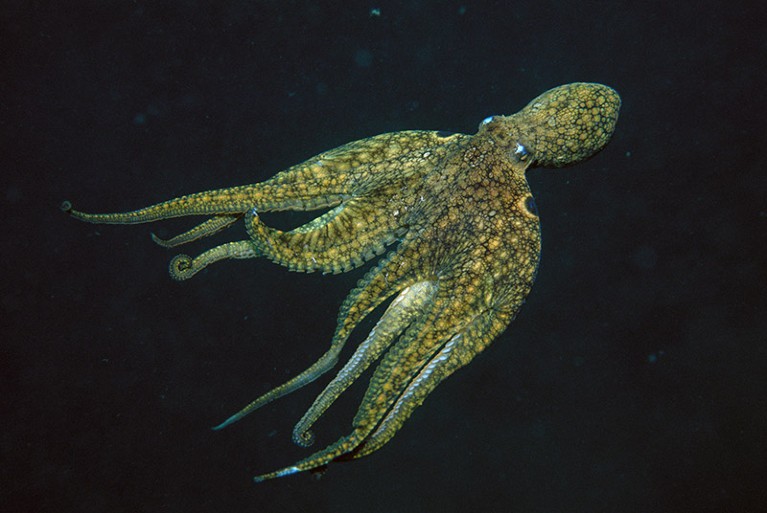

Researchers discovered the chromosome after completing the full gene sequence of the California two-spot octopus. (Image credit: Brent Durand/Getty Images)

They soon noticed that one chromosome, chromosome 17, seemed less filled-out with genes than the other chromosomes in their sequence. Because they had sequenced a female octopus, they compared their results to the earlier individual, a male. In the case of the male, chromosome 17 looked no less populated than other chromosomes in the octopus.

This was a clue that chromosome 17 might have something to do with sex differences. To confirm, the team sequenced four more octopuses, two male and two female, and confirmed that females have just one copy of chromosome 17, while males have two. Thus, they represent the octopus sex chromosomes not as XY and XX as in humans, but as ZZ and Z0.

The researchers then compared their octopus genomes to the genomes of three other octopus species, three species of squid, and the chambered nautilus (Nautilus pompilius).

They found the ZZ/Z0 pattern in the squid and the octopus, but not in the nautilus, a more distantly related species. This showed that the sex chromosomes evolved after the split between the nautilus line and the line leading to modern squid and octopus, which occurred between 455 million and 248 million years ago.

"This is an astoundingly long time for a sex chromosome to be preserved," the researchers wrote in their paper, which is now available pre-peer review on the preprint website BioArxiv.

Prior to this research, the oldest confirmed sex chromosome was in sturgeon fish, according to Nature News, with an age of about 180 million years.

Octopuses Might Have The Oldest Sex Chromosomes in The Animal Kingdom

Cephalopods may have the oldest sex chromosomes of any animal, according to a recent discovery in the octopus genome.

That's a big deal given that scientists didn't know until now that these oddball creatures even had a form of sex determination written into their genes. To determine if an octopus is male or female, biologists have relied purely on observation, differentiating between which individuals lay eggs versus which produce sperm.

Searching the octopus genome had shown no clear sign of a sex chromosome system. Scientists were beginning to wonder if perhaps cephalopods were like some fish and reptiles, with sex determined through environmental factors such as the temperature at which eggs are kept rather than the inheritance of distinct chromosome.

At last, researchers at the University of Oregon claim to have solved the mystery.

Their pre-print study, which is currently under peer review, provides the first evidence of genetic sex determination among octopuses.

Examining the genes of the California two-spot octopus (Octopus bimaculoides) – the first cephalopod to have its whole genome sequenced – researchers have finally found a unique chromosome pair.

They discovered it on chromosome number 17, and it only stood out to researchers when they compared the male octopus genome that had been fully sequenced to a female one. The female octopus seemed to be missing one of their two copies.

Digging further, researchers say they found clear signatures of a ZW sex-determination system, which is seen in birds, crustaceans, and some insects,

We humans rely on an XY system, wherein two X chromosomes create the default female body plan, while the presence of a Y chromosome generally triggers the development of male characteristics.

Octopuses have an opposite system. It is the males that typically have a double-Z pair and females that have only one Z chromosome.

To see if this system was present in other cephalopods, researchers compared the genomes of three octopus species, three squid species, and a nautilus.

They concluded that the Z chromosome is an "evolutionary outlier" that stands apart from similar chromosomes in close relatives.

Only the genomes of the bobtail squid (Euprymna scolopes) and the East Asian common octopus (Octopus sinensis) had similar outlier signatures, but because these creatures are from different lineages, it suggests the Z chromosome originated before their split.

As such, researchers at the University of Oregon argue that the Z chromosome is "of an ancient, unique origin" that probably arose between 455 and 248 million years ago. If the chromosome appeared towards the earlier end of that timeline, the octopus could have the oldest animal chromosome yet found, beating even some insects which are thought to have sex chromosomes that date back 450 million years.

Compared to those of octopuses, however, these arthropod sex chromosomes are poorly conserved across species.

For comparisons, the oldest accepted vertebrate chromosome is that of a sturgeon fish, which is thought to be about 180 million years old. Sturgeon fish females have a ZW sex chromosome set pair as opposed to the female octopus's 'hemizygous' Z chromosome. It's possible the octopus's corresponding W chromosome may have been lost over time in a manner similar to the ill-fated trajectory of the Y chromosome in humans.

The story behind sex chromosomes has changed a lot in recent years. Once, they were thought to be intrinsic features of sex determination in animals. But biological research tends to be biased towards mammals. As it turns out, some fish and reptiles, like crocodiles, don't have sex chromosomes at all. The sex of their offspring is instead determined by other, external factors through epigenetic regulations.

Clearly, there is still much to be learned about how sex chromosome evolved, and why. Octopuses, with their deep evolutionary roots could be fascinating models for future research.

"The data presented in this paper definitely suggests that cephalopods have among the oldest sex chromosomes in both animals and plants," independent evolutionary scientist, Sarah Carey, told Carissa Wong at Nature.

"This is such a cool time to be working on the genetics of sex chromosomes."

The preprint was published in bioRxiv.

Oldest known animal sex chromosome

evolved in octopuses 380 million years ago

Result reveals for the first time how some cephalopods determine sex.

By Carissa Wong

04 March 2024

The California two-spot octopus (Octopus bimaculoides) has one or two copies of chromosome 17, depending on its sex.Credit: Norbert Wu/Minden Pictures via Alamy

Researchers have found the oldest known sex chromosome in animals — the octopus Z chromosome — which first evolved in an ancient ancestor of octopuses around 380 million years ago. The findings1 answer a long-standing question about how sexual development is directed in the group of sea creatures that includes octopuses and squid.

“We stumbled upon probably the oldest animal sex chromosome known to date,” says evolutionary geneticist Andrew Kern at the University of Oregon in Eugene. “Sex determination in cephalopods, such as squids and octopi, was a mystery — we found the first evidence that genes are in any way involved.”

How does it feel to have an octopus arm? This robo-tentacle lets people find out

In many animals, including most mammals and some insects, sex chromosomes determine whether an individual becomes male or female. In humans, females usually have two X sex chromosomes, and males typically have one X and one Y sex chromosome. But for some animal groups, such as cephalopods — which include soft-bodied animals such as squids and octopuses, as well as hard-shelled creatures called nautiluses — researchers have been unsure about how individuals become male or female. Scientists generally thought that environmental factors such as temperature play a part — as they do for some reptiles and fish.

Catching Zs

In 2015, researchers reported2 sequencing a cephalopod genome for the first time — that of a male California two-spot octopus, Octopus bimaculoides. In the latest study1, Kern and his colleagues mapped the genome of a female California two-spot octopus. They discovered 29 pairs of chromosomes and one single chromosome, called chromosome 17. By contrast, the male octopus genome had two copies of chromosome 17. That difference led the researchers to hypothesize that chromosome 17 was a sex chromosome.

Sequencing the DNA of other O. bimaculoides octopuses confirmed the idea. Males always had two copies of chromosome 17, whereas females had one copy. Chromosome 17 also contained several genes similar to those that encode proteins in human reproductive tissues, including a protein found in sperm. In animals including birds and butterflies, males similarly have two Z sex chromosomes, whereas females have one Z and one W sex chromosome.

“It very much looked like we were looking at a Z chromosome in O. bimaculoides,” says Kern. But the researchers failed to find a W chromosome in the female octopuses. That suggested that males have ZZ sex chromosomes, whereas females are ZO, with the O denoting the lack of a W chromosome.

Well conserved

The team also found Z chromosomes in some other octopus and squid species — but not in a nautilus.

“This pattern suggests that the Z chromosome evolved once in the lineage that led to modern squid and octopuses — after this lineage split off from hard-shelled nautiloids,” says Kern. This means the Z chromosome first appeared between 450 million and 250 million years ago and has been retained to the present day, he says. Previously, the oldest known animal sex chromosome was thought to have evolved in sturgeon fish about 180 million years ago3.

This chromosome is profoundly evolutionarily conserved, says Matthias Stöck, an evolutionary geneticist at the Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries in Berlin.

“The data presented in this paper definitely suggests that cephalopods have among the oldest sex chromosomes in both animals and plants,” says Sarah Carey, who studies the evolution of sex chromosomes at the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology in Huntsville, Alabama. “This is such a cool time to be working on the genetics of sex chromosomes.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00637-0

References

Coffing., G. C. et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.21.581452 (2024).

Albertin, C. B. et al. Nature 524, 220–224 (2015).

Kuhl, H. et al. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 376, 20200089 (2021).

No comments:

Post a Comment