The Political Economy and Political Ecology of the Hydro-Social Cycle

We are witnessing something unprecedented: Water no longer flows downhill. It flows towards money

(Robert F. Kennedy Jr.).

Geographers have been engaged in research into access to safe drinking water for years. In fact, Abel Wolman helped chlorinate the world's water. Over the past few years and in the wake of the resurgence of the environmental question on the political agenda, a growing body of work has emerged on the political-economy and political-ecology of water and water circulation (Gandy 1997, Loftus 2005, Kaika 2005, Castro 2006). This is re-defining the contours of water resources research and opening up an exciting and vitally important research agenda for the years to come.

Political-ecological perspectives on water suggest a close correlation between the transfor-mations of, and in, the hydrological cycle at local, regional and global levels on the one hand and relations of social, political, economic, and cultural power on the other (Swyngedouw 2004). In a sustained attempt to transcend the modernist nature – society binaries, hydro-social research envisions the circulation of water as a combined physical and social process, as a hybridized socio-natural flow that fuses together nature and society in inseparable manners (Swyngedouw 2006a). It calls for revisiting traditional fragmented and interdisciplinary approaches to the study of water by insisting on the inseparability of the social and the physical in the production of particular hydro-social configurations (Bakker 2003, Heynen et al. 2005).

Such a perspective opens all manner of new and key research issues and urges considering a transformation in the way in which water policies are thought about, formulated, and implemented. In what follows, an outline is provided of some of the vital issues and socio-natural properties of the hydro-social cycle and charts the terrain for future research.

Metabolizing the Global/Local Hydro-Social Cycle: The Connection to Struggles for Power

Changes in the use, management, and socio-political organization of the water cycle and social changes co-determine each other (Norgaard 1994). Combined with the transformation of water's terrestrial and atmospheric circulation, they produce distinct forms of hydro-social circulation and new relationships between local water circulations to global hydrological circuits. In other words, hydraulic environments are socio-physical constructions that are actively and historically produced, both in terms of social content and physical-environmental qualities. There is, therefore, nothing apriori unnatural about constructed environments such as dams, irrigation systems, hydraulic infrastructures, and so forth (Harvey 1996).

Produced environments are specific historical results of socio-biophysical processes. Most social processes and socio-ecological conditions (cities, agricultural or industrial production systems and the like) are invariably sustained by and organized through a combination of social processes on the one hand (such as capital/labor relations and forms of organization of labor) and metabolic-ecological processes (that is the biological, chemical or physical transformation of ‘natural’ resources, usually organized through a series of interlinked technologies) on the other (Heynen et al. 2005). These metabolisms (for example, the production of potable water, agricultural products or computer chips) produce a series of both enabling and disabling social and environmental conditions. While environmental (both social and physical) qualities may be enhanced in some places and for some people, this often leads to a deterioration of social and physical conditions elsewhere (Peet and Watts 1996, Keil 2000). Processes of socio-environmental change are, therefore, never socially or ecologically neutral. This results in conditions under which particular trajectories of socio-environmental change undermine the stability or coherence of some social groups or environments, while the sustainability of others elsewhere might be enhanced. Consider, for example, how the provision of water to large cities often implies carrying water over long distances from other places or regions. The mobilization of water for different uses in different places is a conflict-ridden process and each techno-social system for organizing the flow and transformation of water (through dams, canals, pipes, and the like) shows how social power is distributed in a given society (Swyngedouw 1999). For example, access to potable water in the megacities of the Global South is precarious for a large number of people despite the fact that the rich and powerful generally have more than enough water available for necessary and luxury use. In sum, the political-ecological examination of the hydro-social process reveals the inherently conflict-ridden nature of the process of socio-environmental change and teases out the inevitable conflicts (or the displacements thereof) that infuse socio-environmental change. Particular attention, therefore, needs to be paid to social power relations (whether material, economic, political, or cultural) through which hydro-social transformations take place. This would also include the analysis of the discourses and arguments that are mobilized to defend or legitimate particular strategies. It is these power geometries and the social actors carrying them that ultimately decide who will have access to or control over, and who will be excluded from access to or control over, resources or other components of the environment. In sum, it will be vital to examine how hydro-social transformations are imbedded in and infused by class, gender, ethnic or other power struggles. These struggles will undoubtedly intensify in the near future as environmental change accelerates and this requires urgent scholarly attention.

Water Scarcities or Water Surpluses?

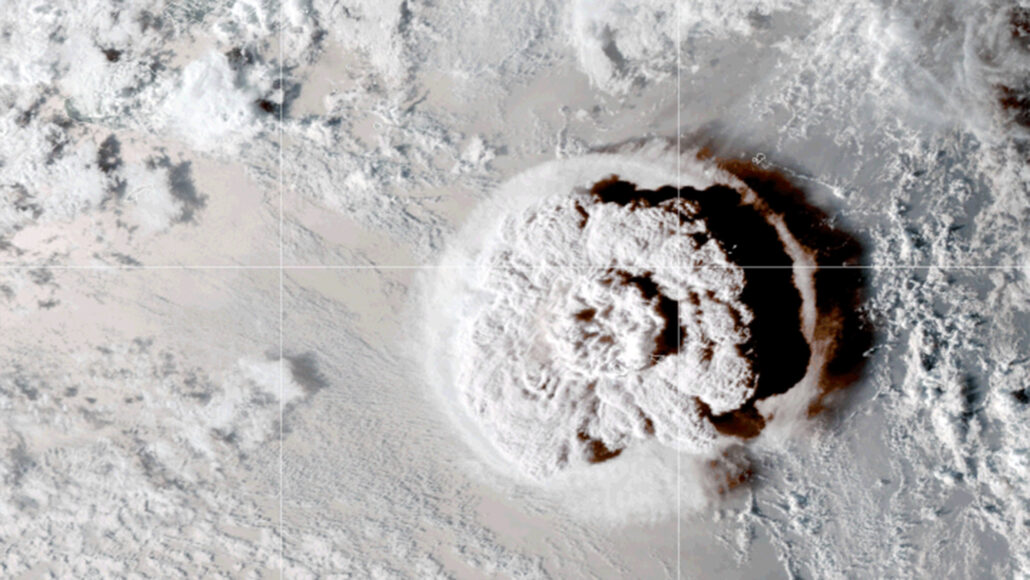

One of the pivotal terrains of environmental social struggle unfolds over access to, control over, and distribution of parts of the hydro-social cycle. Powerful arguments have been mobilized in recent years that frame water as a fundamentally scarce resource in some places on the one hand, and as posing immanent or real dangers due to overabundance in areas prone to flooding, hurricanes, and the like on the other (Bakker 2000, Kaika 2003). This area requires immediate and urgent attention, especially given impacts of climate change. Forms of relative scarcity in relation to existing socio-physical conditions can be observed in particular historical-geographical contexts. And, water power can wreck considerable socio-climatologic havoc (e.g., in New Orleans in 2005 or in the UK in 2007). Just as importantly, the positive and negative socio-environmental consequences of such conditions are socially highly unevenly distributed, and are generated through the particular political and institutional organization of the hydro-social cycle. While hegemonic neoliberal arguments claim that the market offers the optimal mechanism for the allocation of presumably scarce water resources, and the literature on water-related hazards charts the uneven distribution of the social effects engendered by such water crises, a political-ecological perspective insists on, and traces, the fundamentally socially produced character of such inequitable hydro-social configurations (Swyngedouw 2006b, 2007). There is an urgent need, therefore, to theorize and empirically substantiate the processes through which particular socio-hydrological configurations become produced that generate inequitable socio-hydrological conditions. Put simply, interventions in the organization of the hydrological cycle are always political in character and therefore contested and contestable. This intrinsically social character of water resources management and organization needs to be teased out and clarified.

Whose Waters?

The above implies the need to address the question of who is entitled to what quality, kind and what volumes of water and who should control, manage and/or decide how the hydro-social cycle will be organized. While social movements often invoke principles of universal water rights on the basis of the biological necessity of access to minimum volumes of sufficient quality of water in order to sustain bodily metabolisms and social reproduction, such calls for universal water rights are systematically undermined by equally powerful calls related to property rights and the exclusive usage associated with them. In fact, uneven access to or control over water is invariably the outcome of combined geographical conditions, technical choices and politico-legal arrangements and water inequalities have to be understood increasingly as the outcome of the mutually constituted interplay between these three factors. Water research has for too long concentrated on either the physical side or the managerial side of the water problematic, often tiptoeing around the vexed question of how political economic power relations fuse the physical and the managerial together in particular and invariably socially uneven ways.

As Aristotle pointed out a long time ago, when two equal rights meet, power decides. Indeed, under the current neo-liberal hegemony, water rights are increasingly articulated via dynamics of commodification of water, private appropriation of water resources, dispossession tactics, and the like (Bakker 2003). Consider, for example, how in former socialist states or in China publicly owned water facilities and infrastructure have been transferred, often without much compensation, to private actors and capital, or how financial investment funds (of the kind that produced, in 2008, the greatest financial crisis in a century) have been investing in water facilities as a purely financial asset. Macquarie, the Australian investment fund, for example, bought Thames Water, London's water supply system, in 2006. In other words, the hydro-social circulation process is increasingly articulated via the financial nexus (see Swyngedouw 2009).

There is an urgent need to analyze how common or public water rights are socially, politically, and economically transformed into exclusive property rights whose access is choreographed though market mechanisms. There is significant urban-rural tension in this scenario, evident in cities such as Las Vegas (for more see the article by Smith, Jr. in this same volume). Accumulation by dispossession and the systematic inclusion of parts of the hydro-social cycle in accumulation tactics of private actors is rapidly reshaping the mechanisms and procedures that regulate and organize access to, and exclusion from access, to water, and is, consequently, altering the social mechanisms that shape water entitlements and water rights (Harvey 2003). Increasingly, access to water is understood and seen as organized through market mechanisms and the power of money, irrespective of social, human or ecological need.

An understanding of the above is vital in light of the failure of the international community to move decisively towards fulfilling the “Millennium Goal” of halving the number of people worldwide that have inadequate access to water and sanitation by 2015. It can now be confidently predicted that these objectives will not be met, largely because of the hegemony of the neo-liberal model that makes public subsidies unacceptable, while privatizing water delivery systems have systematically failed to alleviate significantly the water crisis in the Global South in places such as Manila, Jakarta, or Lagos (see Swyngedouw 2009). Inadequate access to water services, particularly in the less-wealthy world's megacities, is the prime cause of premature mortality and this human and environmental cost outweighs massively the predicted negative human consequences of global climate change.

Of course, it is invariably the poor and powerless that die of inadequate sanitation (Gleick 2004, Gleick and Cooley 2006). True scarcity does not reside in the physical absence of water in most cases, but in the lack of monetary resources and political and economic clout. Poverty and governance that marginalizes makes people die of thirst, not absence of water. It is these urban political-ecological perspectives that bring out the economic and political power relations through which access to, control over, and distribution of water is organized. While choices regarding what technology is ‘appropriate,’ in terms of being physically, culturally, and economically sustainable and equitable, also play a major role in determining access to safe water in less-wealthy settings (Smith, Jr. 2008), the consideration and implementation of these choices is a decidedly political process and should be analyzed as such.

Governing Hydro-Social Configurations

Hydro-social configurations, of course, generally reflect hegemonic political, social, and cultural preferences. Ever since Karl Wittfogel's seminal work on the relationship between autocratic power and hydrological systems, it has become clear that social power becomes articulated through socio-technical systems (Wittfogel 1957). This is as true for the Three Gorges Dam in China as for the management of the Upper and Lower Colorado River, or irrigation of vineyards in California. There is an urgent need, therefore, to explore the intricate relationship between political systems, and the use, management, and distribution of water and organization of the hydro-social system. In particular, questions arise as to the relationship between democratic governance on the one hand and water management on the other. It is now commonly recognized that many large hydro-social systems are associated with autocratic political and institutional organizations (Worster 1985, Swyngedouw 2006b). The present debate over water resources often sacrifices democratic governance on the altar of technological or economic efficiency, while safeguarding existing power relations. Exploring the relationship between democracy, water governance and social power is a vitally important research question. There are also quality questions to be asked regarding the capacity of democratic and other systems to deal with crises that can be associated with drought, floods, and disease. This is particularly acute as water-related crises are bound to increase both in number and in scale. There is an urgent need, therefore, to consider democratic modes of water governance on a variety of interrelated geographical scales. This is particularly acute in regions with strongly competing water demands (e.g., urban vs. rural demand regarding scarce water) on the one hand, or where significant socio-political tensions propel water to be used as a formidable geo-political weapon (e.g., in the recent threat by Israel to cut off Gaza's water supply).

Imagining Different Hydro-Social Metabolisms

To summarize, there are intricate and multidimensional relationships between the socio-technical organization of the hydro-social cycle, the associated power geometries that choreograph access to and exclusion from water, as well as the uneven political power relations that affect flows of water. There is an urgent need to explore the various ways in which social power in its different economic, cultural, and political expressions fuse together with water management principles, choice of technological systems, and structures of supply, delivery, and evacuation of water. To the extent that there is indeed a close relationship between hydro-social ordering and political-economic configurations or, in other words, between the “nature of society” and the “nature of its water flows,” every hydro-social project reflects a particular type of socio-environmental organization. Imagining different, more inclusive, sustainable and equitable forms of hydro-social organization implies imagining different and more effective, assumingly democratic, forms of social organization. This challenge is probably the most pressing one, and one that requires a sustained intellectual endeavor and the mobilization of significant creative energies of all those who make water their terrain of scholarly work.

Author Bio and Contact Information

Erik Swyngedouw is Professor of Geography at the School of Environment and Development of Manchester University. He previously taught at Oxford University and was Fellow of St. Peter's College. He is the author of, among others, Social Power and the Urbanization of Water (Oxford University Press 2004) and co-editor of In the Nature of Cities (Routledge 2006). He has written extensively on the political ecology and the political economy of water. He can be contacted at erik.swyngedouw@manchester.ac.uk.