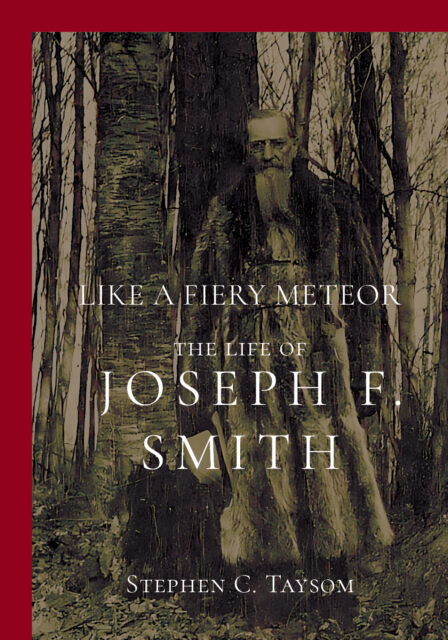

(RNS) — In 2000 and 2001, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints focused its worldwide curriculum on the teachings of Joseph F. Smith (1838 – 1918), a nephew of the founding prophet, Joseph Smith Jr. JFS was the church’s sixth president.

An entire lesson in the manual was devoted to “The Wrongful Path of Abuse,” quoting JFS at length about how violence was “unthinkable” and praising him as a “tender and gentle man who expressed sorrow at any kind of abuse. He understood that violence would beget violence, and his own life was an honest expression of compassion and patience, warmth and understanding.”

The lesson’s claim is not wholly untrue, as historian Stephen Taysom points out in the Afterword of his monumental biography of JFS, “Like a Fiery Meteor.” But it’s certainly selective, since JFS admitted in divorce affidavits to beating his first wife, Levira, in the 1860s; the only part he disputed was whether he’d attacked her with a rope or a small stick. He also verbally abused and threatened her, at one point saying he ought to drill a hole in her head and fill it with manure.

JFS is on record for beating a neighbor almost to death in 1873. There were other stories too, with less clear evidence, including a possible beating of his little sister’s teacher when he was still in his early teens. JFS was a turbulent man who admitted that his temper was the worst part of him and that the only man on earth he ever feared was himself.

But the tender side was there as well, especially toward children. Orphaned at a young age —his father, Hyrum, was murdered in the Carthage Jail in 1844, and his mother died when he was a teen — JFS never lost his sympathy for other orphans. He went out of his way to help, and even adopt, children in need. There’s also no record that JFS was ever violent toward his five subsequent plural wives after Levira.

Both responses — the violence and the compassion — stem from the same early trauma, Taysom said in a Zoom interview. “There was always this constant sense that he was going to lose everything that he cherished,” said Taysom, an associate professor at Cleveland State University who has researched JFS for over a decade.

Taysom points out that JFS’ trauma didn’t end with his father’s murder but was followed by many other deaths. His mother, Mary Fielding Smith (she of the famous story of blessing the oxen on the plains), died when he was 13. As an adult he buried 13 of his 45 children, losses that JFS grieved desperately.

Author and professor Stephen C. Taysom

“That always drove him,” Taysom said. “I’m sure that’s the source of the anger that comes out in him. He doesn’t have great control over the ferocious emotions that he has, whether it’s rage or the grief that he feels for losing a child. He either can’t control it or doesn’t control it, which is different from a lot of people in his world. Even in that context of the 19th-century American West, very few people in the church hierarchy would’ve been as prone to violence as he was. I’m not a psychologist, but the inability to regulate strong emotion can be a hallmark of a traumatized person. He definitely had that.”

Another response was JFS’ unwavering, even fundamentalist, religiosity. In the face of ongoing trauma and poverty, he came to see the church as a holy refuge to be protected at all costs. “He’s unapologetically dualistic in the way he views the world,” said Taysom. “He sees everything as either building up the kingdom or destroying it. He sees the world as this dangerous place that kills righteous things.”

This meant he could be hard on other people, just as he was hard on himself. Despite his deep love for his family, for example, he sometimes subjected them to biting criticism and near-impossible standards. “I never encountered him asking forgiveness for someone or apologizing for something. It just wasn’t part of who he was,” Taysom said.

But that inflexible devotion also meant JFS threw himself wholeheartedly into church service. He went on his first mission at age 15, an orphan sent to sink or swim in the Sandwich Islands (now Hawaii). He swam: There’s a critical scene in the book where JFS preached in sacrament meeting, served the sacrament and then proceeded to excommunicate nine wayward members of the congregation. He was just 17 years old.

Taysom was impressed by JFS’ fierce commitment to education. Because of his parents’ deaths and his ensuing extreme poverty, he received little formal schooling. When he arrived in Hawaii, his letters home showed he was “barely literate.” But he worked at it constantly, reading everything he could and mastering the English language as well as Hawaiian. (Taysom, who has collected some of the books from JFS’ personal library, has his copy of Dante’s “Inferno.”)

“He is certainly one of the most intelligent church leaders we’ve ever had, just in terms of the capacity to learn things, and coupling that with his real desire to put that to use,” said Taysom.

As the years went by and JFS rose in the ranks of church leadership, he directed that self-taught mind to systematizing doctrine and theology. Taysom says JFS is remembered today for his 1918 Vision of the Redemption of the Dead, which codified much of what Latter-day Saints came to believe about eternal families and temple work. But JFS was keenly interested in theology more broadly and regularly fielded doctrinal questions from church members, giving them detailed and logical explanations from the scriptures.

His craving for tidy systems forever changed the previously more haphazard administration of the church. He brought the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve together in purpose — the power struggles between those two bodies are an interesting thread in the book — and foreclosed for all time the possibility of a succession crisis of the sort that had pertained after the death of Joseph Smith Jr. and to a lesser extent after the deaths of Brigham Young and John Taylor.

The death masks of Joseph, left, and Hyrum Smith, created in the Mansion House in Nauvoo, Illinois, by George Q. Cannon after their martyrdom. The masks were donated to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints by the Wilford C. Wood Foundation. Photo by Kenneth R. Mays via Wikimedia Commons

“He imposed an order on things,” said Taysom. “Today, when we ordain somebody to be a deacon, we confer the Aaronic Priesthood on them, and then we ordain them a deacon. But sometimes that was done the other way around until JFS said, ‘No, it has to be done this way because this is how God wants it done.’ So with him, you see this fusion of the performance of things in a certain way and the will of God for them to be that way.”

Smith’s drive to enforce order included an unbending emphasis on sexual purity. He viewed masturbation as a terrible evil (though he couldn’t bring himself to say the word) and believed some Victorian physicians who argued that circumcision could prevent it. So in 1896 JFS arranged for seven of his sons to be circumcised, even though they were far past infancy, then ranging in age from seven to 23. In his mind, whatever pain they experienced from the procedure would be worth it if they could only avoid sin.

Similarly, JFS took a thoroughly uncompromising view of the Albert Carrington case, in which an apostle of the church who had been excommunicated in 1885 for adultery applied in 1887 for rebaptism. Other church leaders leaned toward granting Carrington’s request. “They were saying, ‘Well, Brigham Young would have let him back in,’” said Taysom. But JFS refused, drawing a theological connection between Carrington’s adultery and the “unpardonable sin” mentioned in scripture.

“JFS is saying this is just like denying the Holy Ghost, that it’s a sin next to murder. And so it’s through his writings and teachings that you get this almost strange Mormon way of talking about morality — that when we say ‘immorality’ we mean something sexual, and that you’d rather be dead than have that on your soul.”

In the end, JFS emerges from the biography as a fully drawn human being, full of contradictions. “Some people are going to think I’m trashing him and other people that I’m excusing him,” said Taysom. That makes for a balanced portrait of a complex man who left his defining stamp on The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saint Saints.

Related content in Mormon history:

Spencer W. Kimball diaries shine a light behind the scenes of modern Mormonism

Why Nauvoo still matters