New tsunami risk identified in Indonesia

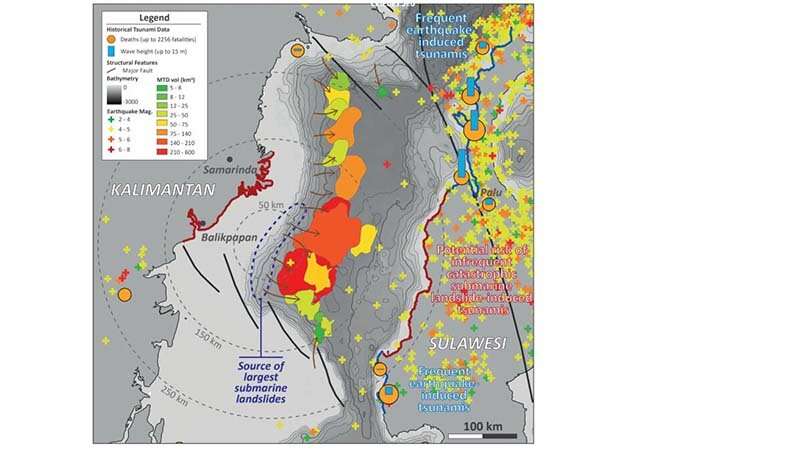

A team of scientists led by Heriot-Watt University has identified a potential new tsunami risk in Indonesia by mapping below the seabed of the Makassar Strait.

The team says their findings mean that coastal communities currently without tsunami warning systems or mitigation systems could be at risk.

The team says their findings mean that coastal communities currently without tsunami warning systems or mitigation systems could be at risk.

This includes the proposed site of the new Indonesian capital on the island of Borneo.

The researchers used seismic data to map underneath the seafloor of the Makassar Strait, a narrow seaway between the islands of Borneo and Sulawesi.

They found evidence of 19 ancient submarine landslides. Submarine landslides have triggered tsunami waves before, such as the 2018 event on Sulawesi in Indonesia, although most tsunamis are caused by large earthquakes.

Dr. Rachel Brackenridge, now at University of Aberdeen, said: "We found evidence of submarine landslides happening over 2.5million years.

"They happened every 160,000 years or so and ranged greatly in size.

"The largest of the landslides comprised 600 km3 of sediment, while the smallest we identified were five km3.

"There will be many smaller events that we have yet to identify."

Dr. Brackenridge explained how they identified the ancient landslides.

"Seismic data allows us to image the subsurface. The different characteristics of rocks below the seabed allow us to reconstruct the conditions they were deposited in.

"We can see a layered and orderly seabed, then there are huge bodies of sediment that appear chaotic.

"We can tell from the internal characteristics that these sediments have spilled down a slope in a rapid, turbulent manner. It's like an underwater avalanche."

The researchers say that the strong ocean current that flows through the Makassar Strait could be behind the prehistoric events and any potential submarine landslides.

Dr. Uisdean Nicholson, who led the research at Heriot-Watt University, said: "The Makassar Strait is an important oceanic gateway. It's through there the main branch of the Indonesian Throughflow transports water—over 10 million cubic metres a second—from the Pacific to the Indian Ocean.

"The current acts as a conveyor belt, transporting sediment from the Mahakam Delta and dumping it on the upper continental slope to the south, making the seabed steeper, weaker and more likely to collapse.

"We estimate the largest, tsunamigenic events—those that displace 100 km3—occurred every 500,000 years.

"Indonesia has mitigation and early warning measures in place in different parts of the country, but not the area that would be affected by a tsunami wave generated from these landslides.

"This includes the cities of Balikpapan and Samarinda, which have a combined population of over 1.6 million people.

"Such an event could be concentrated and amplified by Balikpapan Bay, the site selected for the new capital city of Indonesia.

"Our next step is to quantify the risk in this area by building various numerical models of landslide events and tsunami generation.

"This could help us predict a threshold size that causes dangerous tsunamis and help inform any mitigation strategies.

"We also plan to visit the coastal areas of Kalimantan to look for physical evidence for historic or prehistoric tsunamis, to test the model outcomes and further improve our understanding of this hazard."

Professor David Tappin of the British Geological Survey and UCL was involved in the study, and is working on the Sulawesi tsunami, which struck the opposite side of the Makassar Strait in September 2018.

Professor Tappin said: "The new study on submarine landslides is important in demonstrating that the tsunami hazard in this region of Indonesia is possibly greater than previously thought, but more research is necessary to confirm this."

Professor Ben Sapiie from Institut Teknologi Bandung, Indonesia, said: "This research enriches the Indonesian geological and geophysical communities' knowledge about sedimentation and landslide hazards in the Makassar Strait. The future of earth sciences research is using an integrated, multi-scientific approach with international collaborators."

Dr. Nicholson recently identified ancient submarine landslides near the Falkland Islands in a separate research project.

More information: Rachel E. Brackenridge et al. Indonesian Throughflow as a preconditioning mechanism for submarine landslides in the Makassar Strait, Geological Society, London, Special Publications (2020). DOI: 10.1144/SP500-2019-171

The newly described species Chelus orinocensis is found in the Orinoco and Río Negro basins. Credit: Mónica A. Morales-Betancourt

The newly described species Chelus orinocensis is found in the Orinoco and Río Negro basins. Credit: Mónica A. Morales-Betancourt