The Fight to Defend Abortion Rights

FEMINISM • May 9, 2022 • Erin Brightwell

In many countries around the world, winning or defending the right to abortion access has been a key feature of women’s movements in recent years. From the historic repeal of the constitutional ban on abortion in Ireland in 2018 to the Green Wave movement which won legal abortion last year in Argentina, millions across the world have mobilized to fight for new reproductive rights gains, and to defend abortion rights from right-wing attacks. But these are part of a longer trend: since 2000, 31 countries have expanded access to abortion.

Campaigns to win abortion rights are part of a broader global women’s revolt which has exploded on every continent in recent years. Women have stepped forward to lead movements fighting for feminist demands, and have come to play outsize roles in struggles where the primary demands are not around women’s rights, such as in the revolutionary movements in Sudan and Myanmar. In the years just prior to the pandemic, International Women’s Day was revived as a major event with mass rallies and walkouts in many countries. #MeToo has been a truly international phenomenon, and the fight against sexual violence has fueled movements in the streets in countries all across the world, and spurred a recent wave of high school walkouts in the US.

Attacks by the right-wing on abortion have also been a growing feature internationally, including in the United States. In some countries, right-wing parties and governments, often linked to conservative religious forces, are using the issue of abortion to mobilize their bases. The 2016 Polish “Black Monday” protest saw over 100,000 workers, mainly women, walk off the job to defeat the right-wing Law and Justice party’s attempt to push through a total abortion ban. This protest was a watershed event, inspiring activists and movements around the world to fight for women’s rights in general, and the right to abortion in particular.

Class Society and the Control of Women’s Fertility

With abortion access now under dire threat in the US, and with political polarization increasing generally in many countries, the stage is set for fierce battles against reactionary forces around reproductive rights in the coming year. If the right succeeds in dismantling protection for abortion rights on the national level without an all-out fight to oppose this, it would have significant costs to the credibility of the political establishment. Furthermore, other hard-won social gains such as marriage equality could be the next target of the right-wing agenda.

Women’s oppression has its roots in the origins of class society, when, in order to maintain control of wealth, the male-dominated ruling class needed to ensure a clear line of inheritance. Control of women’s reproduction by the ruling class also has an ideological component. A tiny handful of people cannot expect to maintain control over a brutally exploitative economy if the working class, who represent a majority of society, are united and organized. The ruling capitalist class has always used sexism to divide the working class. Working class men may have no control over their lives while they’re at work, but they are offered instead the domination of their female partner and children according to the ideology of capitalism.

Male domination of the family is now rejected by large sections of working class people in many countries. However, even in countries where women’s mass movements had a transformative impact on women’s roles in society, the idea that men have the right to control women’s sexuality and reproduction persists in different ways, and plays an important role in maintaining divisions in the working class.

As more women go to work outside the home, entrenched views of male domination of women’s sexuality and reproduction tends to weaken as women earn their own wages and have more independence. The monumental women’s movement of the 1960s and 70s in the US occurred as a large influx of women were moving into the workplace. The further globalization of the world economy under neoliberalism led to the growth of industries such as textiles in poor countries and an increase of women in the workforce in many countries. This process is also connected to the increasing urbanization of the population in poor countries.

The increasing presence of women in the workplace worldwide is a key factor in the trend of women demanding freedom from traditional patriarchal control, including on the reproductive front. Social factors, particularly the role in society of organized religion, are also important in influencing abortion restrictions. Positively, internationalism has played a big role in recent years with women’s movements taking inspiration from movements in other countries.

The need for the ruling class to control women’s reproductive capacity continues to be a feature of capitalist society. A number of capitalist regimes today are concerned with the reproduction of the working class and maintaining the population at a level where there will be enough workers to avoid economic stagnation and crisis. In both Iran and China, the regimes are facing long-term trends toward declining population and part of their response has been to strengthen penalties for abortions in Iran, and to begin to restrict abortion access in China.

The Revolt Against Patriarchal Norms

A significant feature of movements for abortion rights in a number of countries, especially in Latin America, in the past period has been women revolting against the social power of the Catholic Church and its highly sexist, even misogynistic policies and practices. The power of the church in many countries has been a form of social control utilized by the ruling class to shore up the capitalist state, and the political elite historically has been tightly linked with the church hierarchy. The legalization of abortion in Ireland and Argentina represents major defeats to the social control of the church. This has been a broad process: pro-abortion protests occurred in several Latin American countries on September 28, International Safe Abortion Day. Significant movements for abortion rights are building particularly in Chile and the Dominican Republic, and in Mexico the decriminalization of abortion was recently won.

Protests erupted again in Poland last year against a new draconian abortion ban imposed by the right-wing government with the full support of the Catholic hierarchy, with which this government is tightly linked. This time, much of protesters’ rage was targeted at the church itself – a sharp development in a country where the church has a special status and role in the state, as it played a major role in the restoration of capitalism following the collapse of the Stalinist regime. Images and videos went viral of a young woman holding a sign saying, “Let us pray for abortion rights,” in front of a church altar, and crowds chanting “fuck the clergy” at a historic church site in Krakow. Unfortunately, the movement in Poland was not able to reverse the abortion law last year, but the protests showed that working class people and particularly young people are becoming increasingly opposed to the domination of religious ideology over some of the most personal aspects of their lives.

Liberalization of abortion laws is occurring around the globe. The longstanding abortions ban was removed by the Supreme Court in South Korea in 2019, where a campaign by activists pushed the regime to act. Abortion has been both widely practiced and deeply taboo in South Korea. Despite being formally illegal since 1953, abortion was relatively easily accessible as the government was interested in reducing population growth, particularly during the 1960s. The situation changed around the turn of the 21st century, when the Korean government became concerned about the slow population growth, and some medical practitioners who performed abortions were prosecuted for it.

This happened against the background of a decades-long increase in the percentage of Korean women who were in the workplace, with an even sharper increase beginning in 2014. In 2017, campaigners gathered over 200,000 signatures for a petition demanding legal abortion. Thousands joined street protests, taking inspiration from the victory of the Irish campaign to repeal the anti-abortion eighth amendment. Public opinion was undergoing a sea change: in 2010, 33% of Koreans supported repealing the abortion ban, but by 2017, 51% did.

Abortion laws have recently been liberalized in Thailand and Benin. A new law loosened abortion restrictions somewhat this year in India, though the procedure still requires a doctor’s authorization and unsafe abortions remain a major cause of maternal mortality. The new Israeli government is discussing relaxing abortion restrictions.

While the general trend internationally is toward women’s movements winning increased abortion rights, there are important exceptions, such as the US and Poland, where abortion crackdowns are used mainly to stoke the voting bases of major right-wing parties, as well as China and Iran. The attacks of the Chinese and Iranian regimes on reproductive rights are more focused on increasing the birth rate in the face of rapidly aging populations, and both regimes also trade in promoting sexist gender roles that emphasize male domination in the family. In China, the regime has moved somewhat cautiously, restricting abortion rights in a piecemeal fashion because they are concerned about provoking a backlash from the world’s biggest working class. In November, the Iranian government approved a broad set of new regulations which restrict women’s access to contraception and strengthen penalties for performing abortions, including potentially the death penalty.

Situation in the US

Since the oral arguments in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case were heard at the Supreme Court on December 1, it is no exaggeration to say that Roe v. Wade, the crowning achievement of the US women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s, is hanging by a thread. It’s fairly clear that the six conservative justices, which include Trump’s three right-wing appointees, intend to uphold the Mississippi law that bans abortion after 15 weeks – the law being challenged in the Dobbs case. The Court could uphold the Mississippi law either by moving the limit for banning abortions from fetal viability outside the womb to 15 weeks, or by dismantling Roe completely and leaving abortion law entirely up to the states. If they choose to weaken Roe by limiting abortion protections to apply only to the first 15 weeks of pregnancy, that will likely be just the first step in removing protection for abortion entirely.

Should the Supreme Court overturn Roe either via Dobbs in 2022 or in a subsequent court case, an enormous swath of the country will lose the right to abortion within weeks or months, meaning 42% of women of childbearing age in the US will live in a state where abortion is illegal. Abortion will remain legal in other states, and clinics in these states will see an increased caseload as women who have the means will travel to get abortion access.

Women seeking abortions who are in the first 10 weeks of pregnancy may be able to use abortion pills at home, which the FDA has recently authorized to be prescribed through telemedicine and sent to patients by mail. However, 19 states currently prohibit telemedicine visits to dispense abortion pills, and right-wing forces in Republican-controlled states are already looking to further criminalize the use of abortion pills. The Biden administration has legal options to challenge the anti-abortion pill laws as a recent piece in the New York Times details. Many women will be forced to seek out illegal and potentially unsafe abortions, or carry unwanted pregnancies to term.

How Did We Get Here?

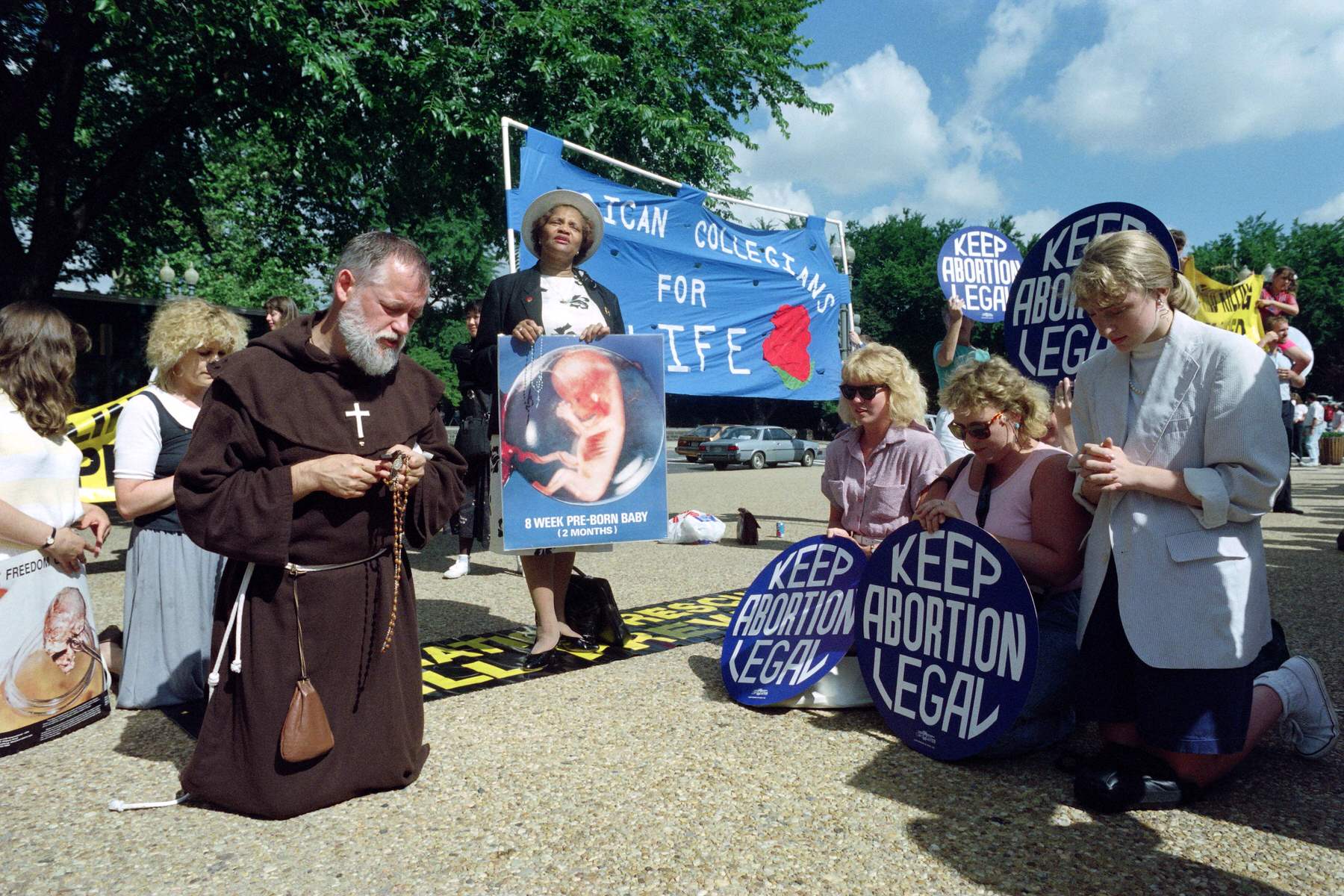

Roe v. Wade established the legal right to an abortion in the US in 1973. For most of the nearly 50 years since Roe, it has been under attack by organized anti-abortion forces that are organized by the Christian Right which represent a powerful Republican voting block. Literally hundreds of laws have been passed by legislatures in Southern and Midwestern states that restrict access to abortion or make it illegal. The courts have overseen the slow chipping away of abortion rights by allowing laws to stand which make abortion more difficult to access, while striking those down that outlaw abortion outright.

Some of the abortion restrictions imposed in Republican-controlled states are inhumane and are evidence of a truly disturbing degree of hatred for women. A 2019 Kentucky law that requires abortion providers to perform an ultrasound, describe the fetus in detail to the patient, and force the patient to listen to the fetal heartbeat before performing an abortion was allowed by the Supreme Court to go into effect. For women who are nine weeks or less into pregnancy, this ultrasound must be done transvaginally – forcing women seeking abortions to undergo a highly invasive and completely unnecessary medical procedure that constitutes a form of assault by the state.

Twenty-six states require women to attend an initial appointment and then undergo a waiting period, which is completely unnecessary on any medical basis, before receiving an abortion. In six states this waiting period is 72 hours, and in one state, Utah, the law specifies that weekends and holidays can’t be included in the 72 hours. Waiting periods especially target working-class and poor women who have to take time off work or arrange childcare for two appointments instead of one. In the many states where there are only a few or even just one abortion clinic, women often have to drive hundreds of miles to get to a clinic for two appointments, and pay for lodging during the waiting period.

The prosecution of women who have had miscarriages and stillbirths has been a horrifically dystopian measure that reactionary state governments and individual district attorneys have taken against mostly poor women. Two women in rural California were charged with manslaughter after they had miscarriages and the prosecutor says they used illegal drugs. One of these women, Adora Perez, remains in jail serving an 11-year sentence. In Alabama, an estimated 500 women have been arrested for pregnancy loss, including a woman who lost her pregnancy when she was shot in the abdomen. (The charges were eventually dropped.) Right-wing authorities are actually stepping up the criminalization of pregnancy, with three times the number of women facing prosecution for allegedly harming their fetus between 2006 and 2020, compared to the period of 1973 to 2005.

The leadership of the anti-abortion right argues that any fertilized ovum constitutes a person, and their concern for “unborn persons” consistently outweighs concerns for the person who is pregnant. This serves as a very thin cloak for the reactionaries’ broader program of trying to turn the clock back to the norms of the traditional male-dominated family as a core unit of society. While a clear majority of Americans agree that women should have the right to abortion, there is a significant right-wing minority, especially within more conservative states, who can be mobilized against abortion rights. This makes abortion one of several useful wedge issues for right-wing politicians whose broader programs of unbridled free market economics – pro-business tax cuts, deregulation and privatization – are becoming less and less popular. At the same time, among younger evangelicals for example, there is less enthusiasm for the anti-abortion and anti-LGBTQ themes of the right.

Abortion has been weaponized in a different way by the Democratic Party establishment, which, despite being dominated by nominally pro-choice politicians, has proven itself of little use in defending abortion rights from right-wing attack. Democrats have long voted for the Hyde Amendment as part of spending bills, which bans the use of federal Medicaid dollars for abortion care. Biden campaigned on a promise to repeal the Hyde Amendment, but promptly abandoned that promise when West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin objected. 2021 saw an enormous escalation in anti-abortion lawmaking with the introduction of over 100 new abortion restrictions, including the horrific Texas abortion ban, and yet the traditional women’s organizations linked with the Democratic Party offered no response in terms of mass actions.

One of Biden’s campaign promises was to codify Roe v. Wade as “the law of the land.” The House has passed the The Women’s Health Protection Act which would guarantee the right to an abortion in law. There’s no doubt that passing it in the Senate will not be easy – it will require eliminating the filibuster and putting heavy pressure on anti-abortion Democratic Senator Bob Casey and potentially Joe Manchin, who has a mixed record on abortion. But the Biden administration didn’t even pretend to try.

The Democrats are now preparing the ground to use the threat to Roe to drive left-leaning voters to the polls in 2022’s midterm elections, when big sections of progressive and especially younger voters are deeply disappointed in the Democrats’ general inaction. A powerful defense of Roe will require mass mobilizations, civil disobedience, walkouts and possibly strikes. The Democratic Party has proven over many decades and countless opportunities that it won’t lead a fight for abortion rights, or anything else, based on a mass movement strategy.

Texas Abortion Ban

On September 1, 2021, the second most populous state in the US suddenly lost meaningful abortion access when the Supreme Court let Texas SB8, the infamous law banning abortions past six weeks of gestation, stand despite the fact that it clearly defies the Roe decision. Since SB8 went into effect, abortion clinics in neighboring states have been overwhelmed by demand from Texans seeking abortions, while the number of abortions performed in Texas has been cut in half. Copycat legislation has been introduced in several states to replicate the legal trick that was used in SB8 to give the reactionary Supreme Court majority an excuse for voting to let the law stand.

The Biden administration and various liberal organizations have launched lawsuits to try and suspend the Texas abortion ban, but the federal courts including the Supreme Court are stacked with right-wing judges appointed by Trump. Some legal challenges to the ban have been thrown out, and others are working their way through courts, but it will likely be years before the lawsuits are resolved, and in the meantime, the law still stands.

While there was a real mood among pro-choice people, and particularly young people, for taking action to oppose SB8 in September, the historic organizations of the women’s movement, that are linked with the Democratic Party, refused to call mass demonstrations. The leadership of Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), an organization with more than 90,000 members, didn’t move to organize demonstrations and build a movement, instead calling for people to give money to abortion funds that help low-income people access the procedure.

Eventually, Women’s March, the organization that came out of the mass protests in 2017, did call nationwide protests for October 2, but left the organizing of them to local affiliates, which in many cases consisted of one or two individuals who weren’t necessarily experienced activists. That tens of thousands of people came out to hundreds of protests all across the country despite the lackluster organization shows the anger that exists against abortion bans and the desire to defend reproductive rights. A big opportunity to bring much broader forces into active struggle was missed due to the absence of leadership from the traditional women’s organizations or from DSA. The right-wing, including the Supreme Court majority, were likely emboldened by the relatively subdued protest response to the Texas ban, and that can have an impact on their deliberations on the Dobbs case.

In Texas, the small forces of Socialist Alternative worked alongside students at University of Houston and organized a student walkout and rally to help build for the October 2 action. Young people showed in the uprising against the murder of George Floyd that they are prepared to take action against injustice and oppression. This fall, young women have led protests and school walkouts against sexual assault at universities and high schools across the country, a development that has mostly gone under the radar in the national corporate media. Stopping the right-wing attack on abortion will require a mass movement that is driven by the energy and radicalism of young people.

What Strategy to Defeat the Right?

The movements that have won abortion rights internationally in recent years show that mass struggle is what is needed to overcome the patriarchal control of women’s bodies that is at the root of abortion bans. Historically, liberalization of abortion regulations has often accompanied movements for the broader liberation of working class people. Abortion was legalized within a few years of the working class taking power in the 1917 Russian Revolution. In South Africa, the right to abortion was passed by the first parliament to be seated after the defeat of the apartheid regime, and abortion was legal for brief periods in Spain in territory controlled by leftist forces during the Spanish Revolution of the 1930s. Abortion rights in the United States were won by the massive women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s which was part of a broader uprising of workers and oppressed people with revolutionary characteristics during the same period.

However, the urgent need for a mass movement to defend abortion rights is not a universally-held conclusion. A layer of left activists, including substantial sections of the active members of DSA, are committed to mutual aid as a key organizing strategy as opposed to mass struggle. This layer will probably look to reinforce existing networks that raise money for working class people to travel to states where they can receive legal abortions, or possibly even develop a safe but illegal abortion service in states with bans.

Mutual aid will no doubt be a huge help for many individuals looking to end pregnancies. The left should set its sights higher, however, and launch a determined struggle for full reproductive medicine including abortion, accessible to all, as part of a Medicare For All system. As the third largest socialist organization in US history, the DSA should take a decisive turn toward taking a lead in mass struggle on abortion and other crucial fights for working class people. To not do so risks the DSA’s becoming completely irrelevant as a force that working class people will look to in struggle

Publicly defying abortion bans by taking abortion pills in a very visible way, and linking this action to a mass campaign, was a potent tactic in building support for ending the Irish abortion ban. The use of abortion pills, which can now be legally dispensed through the mail, as a direct action tactic has been employed at a recent Supreme Court protest. Whether this kind of action will be a key feature of the abortion fight in the US seems less likely, although abortion pills obtained legally or not will undoubtedly be utilized more if the Court does dismantle Roe.

In Ireland, the reactionaries were already very much on the defensive in the run up to the 2018 referendum which made the public defiance very effective in exposing their weakness and hypocrisy. The situation in the US today is not the same, as the reactionaries have consolidated their control over big parts of the country as well as the Supreme Court, and will likely make further gains in the 2022 midterms. This in no way means that we should be defeatist, but it makes crystal clear that only a determined and sustained mass movement can defeat the reactionaries here. The use of abortion pills can be an important auxiliary in this struggle but it will not be the central tactic.

As we approach a spring where the Democrats and the liberal establishment will likely ensure that the impending Dobbs decision stays in the news cycle, the idea that we just need to vote Democrat will be repeated by politicians, the liberal media, and other figures in the Democratic Party orbit ad nauseam. Even when elements of the establishment, such as the Democratic Party – aligned women’s organizations, do organize marches or days of action, the main message from the rally stage will likely be to go vote for Democrats in the midterms. This will fall flat with many young women as young people generally are the most disillusioned in Biden, having had the fewest illusions to start with. A key role of revolutionary socialists is to counter the failed strategy of vote–blue–to–defend–Roe and to raise the need to build a mass movement with new organizations of struggle that are independent from the Democrats and their record of failure on defending abortion rights.

At this moment of overlapping public health, political, and economic crises, a disruptive mass movement on abortion rights is not what the Biden administration wants. However, the capitalist class is too divided and Biden and the Democrats are too weak to lead a progressive advance to codify Roe. Biden is amassing a long list of legislative failures: voting rights, labor law reform, policing reform, and most recently the Build Back Better debacle. The possibility of defending and extending abortion rights depends on the development of a youthful, combative and sustained mass movement.

If Roe is dismantled by the Supreme Court, and especially if a substantial mass movement doesn’t develop in response, the consequences are very serious for working class people. It would be the biggest victory for the right in a generation. In addition to the horrific hardships imposed on women by abortion bans, the right-wing could be emboldened to go even further in rolling back other basic human rights that rest on the same fragile legal foundation as Roe. Marriage equality would likely be the next target. Arch-conservative legal arguments hold that abortion, birth control, interracial marriage, and LGBTQ rights are not explicitly referred to in the text of the constitution and therefore are issues that should be left up to the states. Ultimately our rights are not guaranteed by the Supreme Court or capitalist democracy, but by the strength of working-class and oppressed people’s movements to defend those rights.

The road to a victory for the left in the US on abortion rights is nothing if not difficult and uncertain. Building a sustained mass movement, throwing up new organizations of struggle, developing a capable leadership, and avoiding the trap of the Democratic Party are some of the many tasks ahead of us. But in this struggle we can take inspiration from the victories of mass movements around the world in expanding reproductive rights, from Argentina and Mexico to Ireland and South Korea, and from the reality that the majority of working class people in America oppose the reactionary agenda of the right. •

This article first published on the Socialist Alternative website.