___

Author: Alexander Carpenter, Professor, Musicology, University of Alberta

When Robbie Robertson died on Aug. 9, his death was well-covered by the media, from mainstream news outlets to a wide variety of music magazines, and across the blogosphere. Robertson died at age 80 after a long illness.

In most cases, Robertson’s legacy was afforded a very appreciative but overall sober analysis. This is not always the case, of course, when a “legend” passes away: in the aftermath of Gordon Lightfoot’s death, for example, critics and commentators piled the praise high and deep, with little care for objective evaluation.

Canadian musician, American music

Robertson was, like Lightfoot, a Canadian-born musician of considerable renown, but it seems to me that his death has provoked a very different response.

While one can readily find references to Robertson as a “Canadian music legend” — and even a tweet from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau lauding Robertson as “a big part of Canada’s outsized contributions to the arts” — most eulogies do not dwell or try to force the issue of music and national identity into the foreground.

Even Trudeau’s comments seem rather generic and half-hearted compared to his effusive praise for Lightfoot as one of Canada’s “greatest performers” who “captured the Canadian spirit.”

To do the same for Robertson — who made his name in the American music scene — would be ridiculous.

Robertson and Lightfoot were of the same vintage. They were born within five years of each other, in southern Ontario, and had a similar musical pedigree. Both started writing songs and performing quite young. Both were in the orbit of Toronto-based rock'n'roll legend Ronnie Hawkins (who fronted The Hawks, the pre-fame incarnation of The Band). And both enjoyed long careers that included recognition from the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame.

Indeed, both men have been celebrated as great songwriters, but the essential difference, it seems to me, is that Robertson was a more cosmopolitan, eclectic and versatile performer and composer. And unlike Lightfoot, Robertson couldn’t read or write music.

Touring with Dylan

Robertson’s stint as part of Bob Dylan’s band through the mid-1960s, as Dylan toured the world with a new, electrified sound, was surely part of this cosmopolitanism. After leaving Dylan, this supporting band would become The Band, with Robertson as its chief songwriter.

The Band would go on to make an indelible mark on the history of rock. The group’s loose, raw sound and seamless blending of styles, from rock, soul, rhythm and blues to gospel country and roots, would influence other superstar performers — notably Eric Clapton — to strip down their own musical approach, and develop a new, more authentic aesthetic (Robertson and Clapton would go on to collaborate a number of times).

The Band’s most successful songs — “The Weight,” “Life is a Carnival,” “The Shape I’m In” — were all written by Robertson, and are the songs most often covered by other artists.

The Band would become famous for its first two albums, 1968’s Music from Big Pink and The Band, released the following year. They would go on to record a total of 10 studio albums.

The Band performed at Woodstock and other major festivals in the U.S. However, Robertson would effectively leave the group in 1976: he was tired of touring and was reluctant to work with the other members due in part to their heroin addictions.

By the time Robertson stopped touring and recording with The Band, he had been producing albums for other musicians — including Neil Diamond — and was on his way to becoming a successful film producer as well. The Band would continue recording and performing live well into the late 1990s — without Robertson — finally breaking up for good when bass player Rick Danko died in 1999.

Robertson undertook his own solo career in the late 1980s, recording and releasing six solo albums between 1987 and 2019.

Composing for film

Of course, Robertson also differed significantly from Lightfoot in that he had a long and successful career as a composer for films.

Robertson collaborated with director Martin Scorsese for nearly half a century, serving as Scorsese’s music consultant and composer for many of Scorsese’s movies. Robertson was credited in almost 20 Scorsese films, if you include Robertson’s performance in The Last Waltz, the 1976 film Scorsese made of The Band’s final concert with its original line-up.

A paradoxical figure

Robertson, ultimately, was something of a paradoxical figure. He was Canadian-born and cut his teeth in the Toronto music scene. But he ended up first backing up the quintessentially American folk music legend Dylan, and then becoming the primary creative force in a group — The Band — whose sound was rooted in American music, and especially the musical traditions of the American south.

Robertson also had a different connection to place than his fellow Canadian Lightfoot, having been born on a reserve to a Mohawk and Cayuga mother. Robertson’s love of music was catalyzed by the musical culture on the reserve, and his music continued to reflect these deep roots well into his later years. This happened most notably as part of his collaboration with Indigenous musicians for the 1994 documentary soundtrack Music for the Native Americans.

Robertson’s birthplace and ethnic background — Canadian-born, half-Mohawk/Cayuga, half-Jewish — lent itself from the start to what would become Robertson’s signature approach to song composition. Robertson favoured cultural blending and border-crossing, ignoring genre boundaries and creating something new and engaging out of a patchwork of possibilities.

In its obituary for Robertson, the New York Times went so far as to highlight the paradox of Robertson and his music by crediting him as the “Canadian songwriter” who created the “Americana” genre.

Lightfoot, to my ear, was a songwriter who wrote country-folk tunes that were very much of their time, and that fans and critics sometimes shoe-horned into “Canadiana.” Robertson, by contrast, was a fellow Canadian, and wrote music that was worldly, richly textured and without borders.

___

Alexander Carpenter does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

___

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Disclosure information is available on the original site. Read the original article: https://theconversation.com/the-bands-robbie-robertson-leaves-behind-a-legacy-of-rich-worldly-music-211405

Alexander Carpenter, Professor, Musicology, University of Alberta, The Conversation

Robbie Robertson: A Transcendent Musician Who Bridged Cultures, But Never Forgot his Native Roots

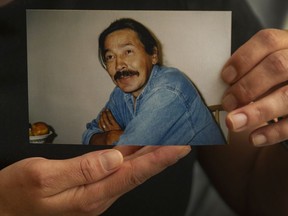

A young Jaime Royal "Robbie" Robertson on the Six Nations of the Grand River reserve near Brantford, Ontario in the 1940s.

BY LEVI RICKERT AUGUST 15, 2023

Opinion. Music icon Robbie Robertson (Mohawk/Cayuga) walked on last week after a long illness at the age of 80. His manager of three decades, Jared Levine, said Robertson was surrounded by his family as he moved to the spirit world.

He was born Jaime Royal Robertson on July 5, 1943 to Rosemarie Dolly Chryler, a Cayuga and Mohawk woman. For the first six years of his life, Robertson, an only child, grew up on the Six Nations Reserve, an hour’s drive from Toronto. He often said later in life that when he was a kid, everyone he knew on the reserve played an instrument. “All my cousins, my uncles,” he said. “And I thought, I’ve got to do this.”

In his teens, his mother told him that James Robertson, the man she had married while pregnant, was not his biological father. His natural father was a Jewish man named Alexander Klegerman, who died in a highway accident before he was born.

Given the long history of Native Americans and Jewish people suffering injustices, Robertson wrote about himself in his memoir, Testimony, “You could say I’m an expert when it comes to persecution.”

Perhaps this expertise helped fuel his extraordinary talent as a songwriter and musician. His contributions to popular music have made him one of the most renowned songwriters and guitarists of his time. In the 1960s, he rose to worldwide fame touring with Bob Dylan as part of the Minnesota singer-songwriter’s backing band, which eventually became known as The Band.

The Band’s blend of traditional country, folk, blues, rock and some occasional old-time music won them critical acclaim in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, laying the foundation for roots music that later became known as “Americana” — which is slightly ironic given that Robertson and three of his four other Band-mates were born in Canada.

After The Band broke up, Robertson embarked on a solo career that included solo records, soundtracks, a memoir and a handful of film appearances. He maintained a 55-year working relationship with Martin Scorsese, writing scores for the award-winning filmmaker’s Raging Bull (1980), The King of Comedy (1983) and Casino (1995), among others. Robertson’s last collaboration with Scorcese was to craft the music for the upcoming Killers of the Flower Moon, which follows a string of murders of Native people in 1920s Osage County.

What is particularly great about Robertson, who gained worldwide fame as a multi-talented music artist, was that he never forgot who he was as a Mohawk and Cayuga person. In 1994, he teamed with the Native American group called the Red Road Ensemble for Music for the Native Americans, a collection of songs composed for a television documentary.

In 1998, he released Contact from the Underworld of Redboy, an album that blended Aboriginal Canadian music with electronic, trip hop and modern rock sounds. The album demonstrated his true ties to his Native American heritage and his support of the mission of the American Indian Movement.

One particular song on the record, Sacrifice, highlighted the plight of Native American activist Leonard Peltier, who was serving two life sentences in prison for a crime he did not commit. The song mixes traditional singing and drums with Robertson’s own voice singing the chorus and a recording from a phone call with Peltier in prison, where the Lakota man tells his story:

“My name is Leonard Peltier

I am a Lakota and Anishnabe

And I am living in the United States penitentiary

Which is the swiftest growing

Indian reservations in the country

I have been in prison since 1976

For an incident that took place on the Oglala-Lakota Nation.”

Robertson amplified Peltier’s story in interviews with the press, telling Rolling Stone magazine: “Of the three people who were charged, the other two were found not guilty by means of self-defense. When that happened, the authorities said ‘Hold on, what’s happening here? Who do we have left?’ Leonard was the one who hadn’t been put on trial. They hand-picked the judge, they moved his trial to another state — he was a sacrificial lamb.”

Peltier remains imprisoned. His attorney, Kevin Sharp, told me on Saturday night that Peltier has been in lockdown for some time and believes Peltier may not even have known of Robertson’s passing.

On Friday, the American Indian College Fund issued a statement about Robertson’s passing: “Robertson’s Indigenous heritage had a profound impact on his music, and he continued writing and exploring his heritage through music. He said he supported the American Indian College Fund because of its wide reach across Indian Country and ability to help Native communities through education.

“They’re the best charity in Indian Country,” Robertson said in a 2007 press release after he teamed with Martin Guitars to create a limited edition guitar modeled on the 1919 Martin he used to write the Band’s hit single “The Weight.” Sales of the special edition helped benefit the American Indian College Fund.

Even as he rose to worldwide fame, Robertson never forgot his roots as an Indigenous man, who also happened to be part Jewish, part Canadian, and an architect of American music in the 1970s. Like his music, Robertson was transcendent, a one-of-a-kind mix of bloodlines, influences, styles and life experiences who gave so much to the world—throughout all of Indian Country and far beyond.

Thayék gde nwéndëmen - We are all related.