BY MARY ANNE TRASCIATTI

MAY 24, 2023

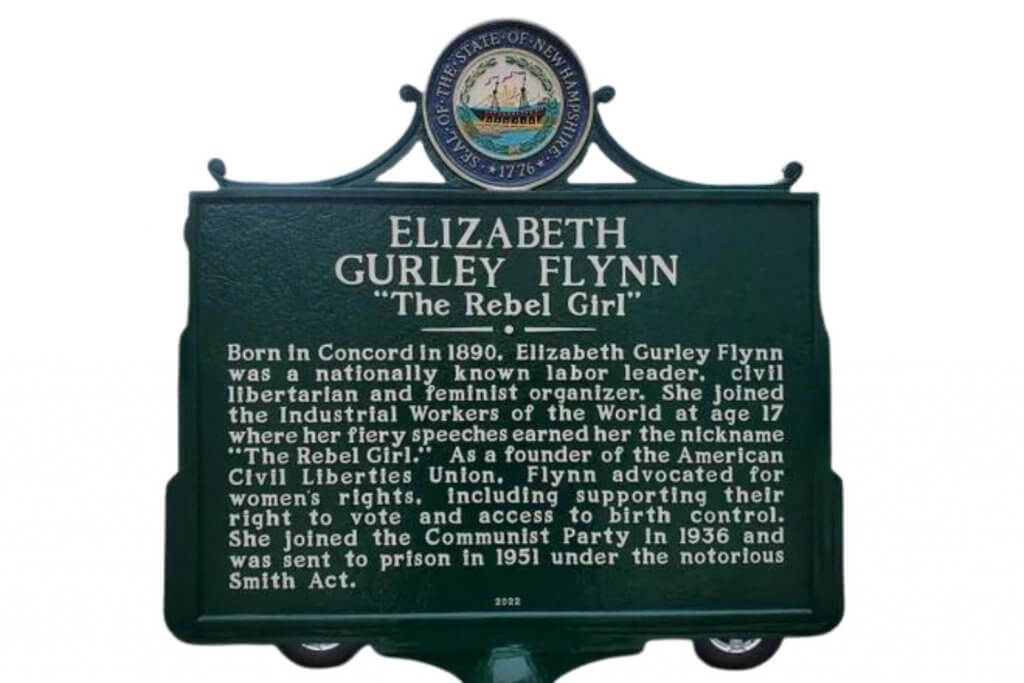

If you blinked, you might have missed the historical marker dedicated to Elizabeth Gurley Flynn at the site of her childhood home in Concord, New Hampshire, on May 1, 2023. That’s because Republican lawmakers had it removed just two weeks after it was unveiled, arguing that Flynn did not deserve such recognition because she was “un-American.”

They based their charge on her membership in the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA). Flynn joined the Party during the Popular Front period and remained a member until her death in 1964.

The marker does not shy away from this history. It explicitly states that Flynn was a Party member and that she was sent to prison under “the notorious Smith Act,” a reference to the 1940 law that made it a crime to advocate the violent overthrow of the federal government. Although it was supposed to protect the nation from Nazis as well as Communists, the law –like most anti-subversive legislation — was used almost exclusively as a weapon to bludgeon the Left.

Early in the Cold War, in 1948, at the urging of J. Edgar Hoover, federal agents arrested CPUSA leaders around the country and brought them to trial, presenting dubious evidence, much of it provided by paid informers, to secure convictions. In 1951, the Supreme Court upheld the convictions in Dennis v. United States. Almost immediately after that decision was announced, Flynn and several other Communists were arrested and indicted under the Smith Act. In 1953, all of them were found guilty.

After the appeals were exhausted, Flynn served twenty-eight months in prison. She was nearly sixty-seven years old when she was released in May 1957. Two months later, the Supreme Court decided in Yates v. United States that the First Amendment protects radical speech, which effectively ended Smith Act prosecutions. Now, nearly seventy years after her Smith Act conviction, when the Cold War is supposedly over, Flynn is once again being penalized for her political ideas.

If Flynn were around today, she would undoubtedly unleash her quick wit and sharp tongue to roast her critics. And she would be justified. To label her un-American is preposterous. Most of her life was spent fighting with and for working people in the U.S. During her years with the Industrial Workers of the World, she led organizing drives, strikes, and free speech fights. She had toyed with the idea of becoming a Constitutional lawyer, but instead, she studied the Constitution on her own, becoming an expert of sorts on civil liberties. In 1918, she founded the Workers Defense Union to aid labor activists whose First Amendment rights were endangered by the wartime Espionage Act and to advocate for recognition of political prisoners by the federal government.

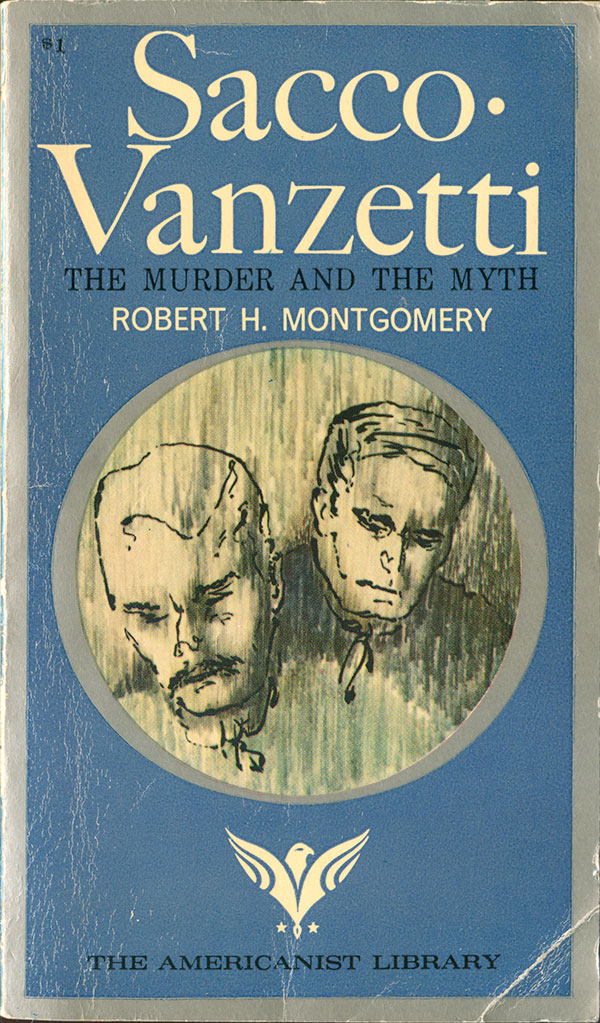

Flynn used this experience as a founding member of the ACLU and she acted as a bridge between the liberals in that organization and the radical labor activists they had pledged to defend, including Sacco and Vanzetti. Long before most Americans understood the danger posed by Mussolini, she recognized his fascist regime as a threat to democracy around the world and spoke against it. She also opposed the Ku Klux Klan, which she saw as a uniquely American fascist organization.

Flynn’s commitment to the struggle for Black liberation was unsurpassed among white activists of her era. She campaigned alongside Black comrades against lynching, suppression of voting rights, housing discrimination, job discrimination, education discrimination, and police brutality. In the final years of her life, when she was appealing the denial of her passport under Section 6 of the McCarran Act, she wrote numerous articles in which she argued that freedom of movement was necessary for the exercise of one’s First Amendment rights. All Americans should be this un-American.

While I bristle at the claim that Flynn (or, as New Hampshire Executive Councilmember Joseph Kenney called her, “someone like that”) does not deserve to be commemorated in public space, I also regret the way that New Hampshire activists chose to remember her. The plaque in Concord identified Flynn as a “nationally renowned labor leader” whose “fiery speeches” earned her the nickname “the Rebel Girl.” Yet it also claimed that Flynn worked through the ACLU to advocate for women’s rights, particularly suffrage and birth control. That claim is simply not accurate. Flynn was not a proponent of voting until she joined the CUPSA and cast a ballot for Roosevelt in 1937. Although she fought for the right of Margaret Sanger to speak about birth control, the issue was not a priority for her. The idea that Flynn was primarily a women’s rights activist has also seeped into media coverage of the controversy over the plaque. The Washington Post, for example, bears a headline that refers to Flynn as “feminist, with Communist past.” She would be surprised to see herself described this way, even if she espoused many ideas that we think of as feminist.

Moreover, Flynn would recoil at the subordination of “Communist” to “feminist.” From the moment she joined the CPUSA until the day she died, Flynn saw herself as a Communist – no qualifier. The movement to which she dedicated her life was, in her own words, “the working-class movement” and the organization that she believed best advanced the interests of the working class was the Communist Party of the United States. In fact, when she was faced with a choice between the ACLU and the CPUSA, she chose the latter. Her refusal to let the ACLU dictate her politics resulted in her expulsion from the organization in 1940.

We can debate her decision to join the Party or to stay with the Party as long as she did. Nevertheless, if we are going to commemorate Elizabeth Gurley Flynn or any other controversial figures whom we believe have made important and valuable contributions to U.S. society, we should commemorate them as they really were, not as we want to see them. In the case of Flynn, the epitaph from her tombstone in Forest Home Cemetery, where her ashes lie near the graves of the Haymarket Martyrs, may offer the best guidance:

“The Rebel Girl”

Fighter for Working Class Emancipation

Credit: Einar E Kvaran aka carptrash courtesy https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Elizabeth_Gurley_Flynn#Media/File:Elizabeth_Gurley_Flynn_gravestone,_Chicago,_IL,_USA.jpeg

Mary Anne Trasciatti

History.acadiau.ca

Archive.org