“Everything should be done to keep alive the tragic affair of

Sacco and Vanzetti in the conscience of mankind.”

ALBERT EINSTEIN, 1947

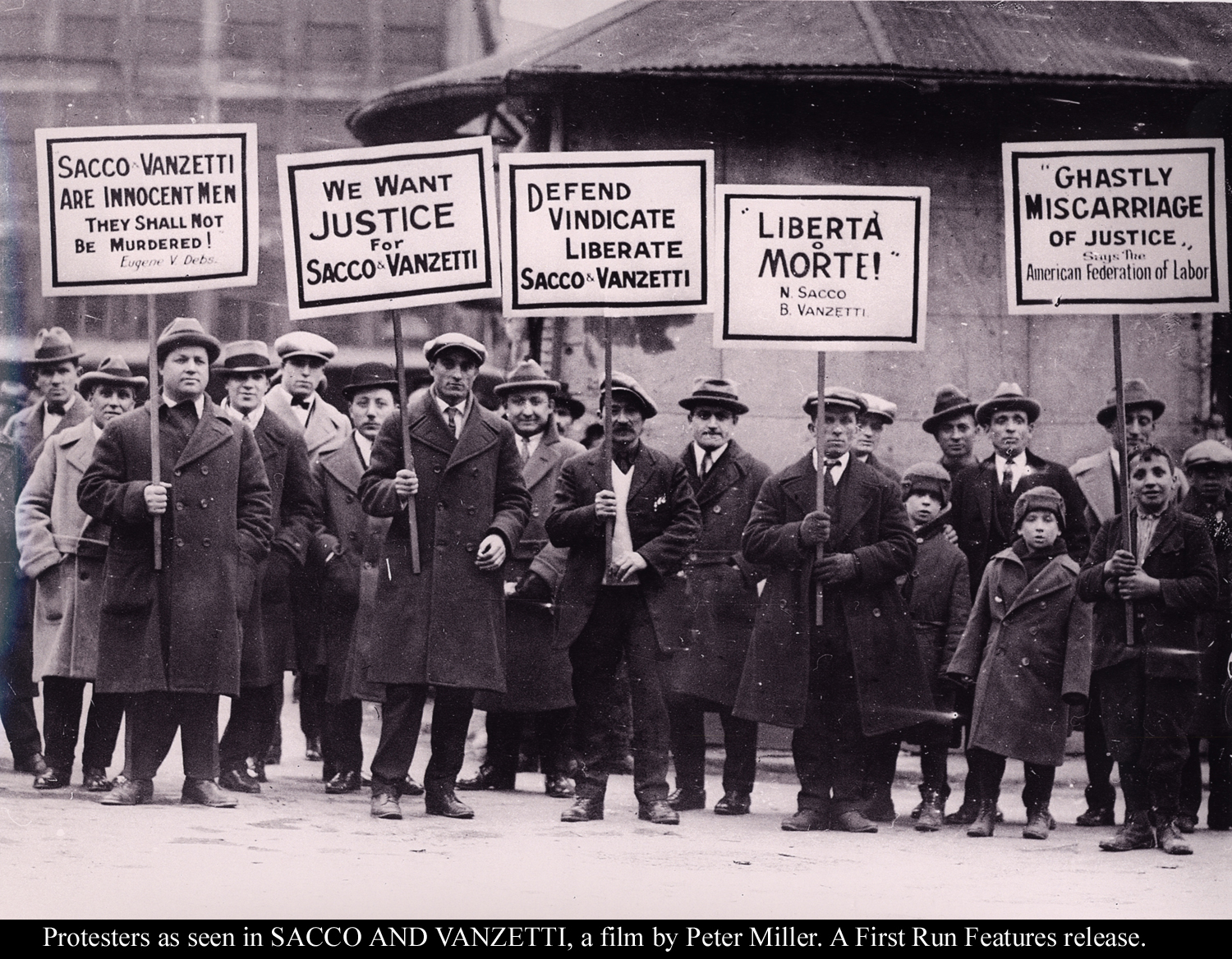

Thursday, Aug. 23, marks the 80th anniversary of the executions of

Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, Italian immigrants and anarchists,

for crimes they did not commit. The south plaza of New York's Union

Square will be the site of a commemoration of the judicial murder of the

two Italian anarchists, at 6 p.m. Union Square was the site of a

historic mass protest by over 500,000 supporters of Sacco and Vanzetti

on the day they were hung. Participating in the commemoration on

Thursday will be:

* The Living Theater, with a performance of a scene from their landmark

play, Paradise Now.

* Ahsanullah Khan, immigrant rights activist.

* Robert Palmer, Libertarian Book Club, speaking on the anarchist

background of Sacco & Vanzetti

* Other musicians and spoken-word artists to be announced.

The previous evening, Wed., Aug. 22, at 7 p.m., St. Joseph's Church, 371

Sixth Avenue in Greenwich Village (northwest corner of Washington

Place), a teach-in will be held on the case and its continuing

importance. The program will include:

* A performance by Leonard Lehrman of excerpts from his completed score

to Mark Blitzstein's opera, Sacco and Vanzetti.

* A screening of Peter Miller's acclaimed documentary, Sacco and Vanzetti.

* A staged reading of Events & Victims, by Daniel Lang/Levitsky.

* A discussion of the case's continuing importance, facilitated by Mary

Anne Trasciatti, assistant professor and chair of the Speech

Communication, Rhetoric & Performance Studies Department at Hofstra

University.

August 21, 2007

Sacco and Vanzetti Now Available on DVD!

To All Documentary Film Fans:

First Run Features is proud to announce the release on DVD of Peter

Miller's acclaimed documentary, Sacco and Vanzetti.

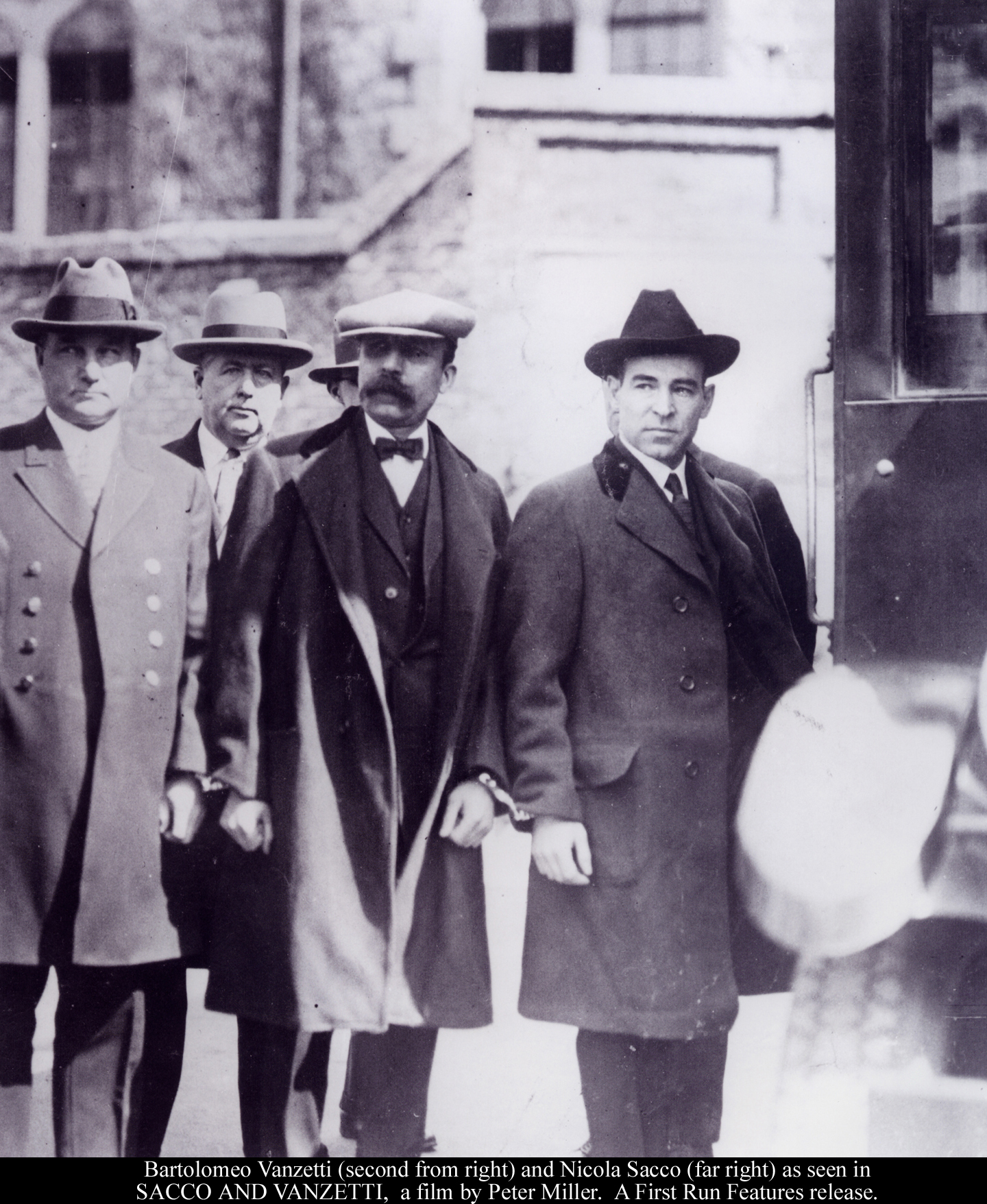

For five years, Miller devoted his life to making a film about an

important event in the history of America - an event that a lot of people

have heard of, but may not know much about. It's the story of Nicola Sacco

and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two Italian immigrant radicals who were accused

of a murder in Boston in 1920, and executed after a notoriously prejudiced

trial.

When we read in the newspaper today how certain immigrants are treated in

this country, it makes us realize that in many ways not much has changed

since the days of Sacco and Vanzetti. If you're from "somewhere else" and

have an accent, or a different skin color, you most likely have to endure

discrimination, resentment, and even violence. And when the government

enacts policies that cut back on civil liberties in the name of protecting

our freedom, how can we not be reminded of the disastrous "red scare" that

set the scene for the Sacco and Vanzetti trial?

If you're interested in the history of America, or the plight of

immigrants, or insight into famous trials and how the law is selectively

applied, or if you're passionate about the death penalty, or concerned

about the protection of our civil liberties, you'll not only enjoy "Sacco

and Vanzetti" but learn a lot from it. If you're fans of Tony Shalhoub

(Monk) or John Turturro (Miller's Crossing), the actors who generously

lent their talents to give voice to Sacco and Vanzetti, or if you

appreciate historians and writers like Howard Zinn and Studs Terkel, or

musicians like Arlo Guthrie, you'll enjoy the film. And if you've got any

Italian in you, this is a must-see.

First Run is offering Sacco and Vanzetti for 25% off the list price of

$24.95. Here's the link to read more about the film, or to purchase it.

Thanks for reading about this, and for helping us get the word out about

this film. Please pass this letter on to anyone you think might be

interested. Also, check out Miller's earlier film The Internationale - a

powerful documentary about music and social change.

Many thanks,

Your Friends at First Run Features

Acclaim for Sacco and Vanzetti!

"Absolutely engrossing! This riveting film masterfully revives the

past."-CHICAGO TRIBUNE

"A rabble-rousing tribute!"-NEW YORK MAGAZINE

"A timely reminder of how things can go when politics obscure reasonable

minds."-BOXOFFICE.COM

"It's cleansing to see the facts laid out with intimacy and rigor. Grade

A!"-ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY

"Thoughtful and thought-provoking!"-LOS ANGELES TIMES

"Superb! A concise yet passionate history lesson whose relevance could not

be timelier."-VARIETY

"A must for history buffs! Thorough and interesting throughout."-SALON.COM

"A wonderful film, as timeless as the struggle for human justice, as

relevant as today's headlines."-KEN BURNS

DVD Bonus Features:

Interview with Director Peter Miller

Sacco and Vanzetti F.A.Q.

Archival Photo Gallery

Suggested Readings

| STANLEY KAUFFMANN ON FILMS Crimes Revisited Post date 04.01.07 | Issue date 04.02.07 |

n the morning of August 24, 1927, a few weeks before I started high school, I read the headlines in The New York Times announcing the executions of Sacco and Vanzetti. I knew something about their story--newspapers and magazines had been brimming with controversy over it ever since I had been able to read--and my parents and their friends had often discussed it. Whatever the rights and wrongs of the matter, I thought, at least the story is now finished. Last week I saw a new documentary about the case.

n the morning of August 24, 1927, a few weeks before I started high school, I read the headlines in The New York Times announcing the executions of Sacco and Vanzetti. I knew something about their story--newspapers and magazines had been brimming with controversy over it ever since I had been able to read--and my parents and their friends had often discussed it. Whatever the rights and wrongs of the matter, I thought, at least the story is now finished. Last week I saw a new documentary about the case.

Peter Miller, who has worked with Ken Burns, made Sacco and Vanzetti because he feels that the red scare of the early 1920s has an analogue in current fears and jingoism. Even though the story is not much of a parallel with our current miring in mendacity, it shocks in two ways: it shows us how recently, relatively speaking, racial and political prejudices were openly allowed to smirch justice; and it makes us take a look at the vitality of liberalism now. Would such an outrage cause an equivalent storm today?

Nicola Sacco (April 22, 1891 – August 23, 1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti – (June 11, 1888August 23, 1927) were two Italian-born American anarchists, who were arrested, tried, and executed via electrocution in Massachusetts for the charge of murder and theft. There is much controversy regarding their guilt, stirred in part by Upton Sinclair's 1928 novel Boston. Critics of the trial have accused the prosecution and trial judge of allowing anti-Italian, anti-immigrant, and anti-anarchist sentiment to influence the jury's verdict. However, Upton Sinclair had brief doubts as to their innocence based upon a later conversation with their lawyer, doubts which, upon further investigation and reflection, he found to be unjustified.

In the August 14th, 2006 issue of the Nation Magazine, there’s a review of recent books on Upton Sinclair by Brenda Wineapple that contains the following observation on the muckraking novelist’s involvement with one of the landmark political trials of the 20th century:

“On the whole, Bachelder’s perspective on Sinclair’s unsinkability seems right. Just last December, Sinclair was resurrected and assassinated all over again when the Los Angeles Times ran a story, bruited in the conservative press, about the recent purchase of a Sinclair letter in which he admitted that one of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti’s defense attorneys had told him that the two Italian anarchists were guilty as charged, and yet he published the novel Boston anyway, to peddle sympathy for them. Neither Mattson nor Arthur would be surprised by the revelatory letter. Each of them amply demonstrates that Sinclair doubted the innocence of at least one, if not both, of the defendants.”

Although Wineapple is understandably focused on Sinclair’s reputation, it is too bad that she allows the reader to assume that Sacco and Vanzetti were guilty. This charge has been made mostly by rightwingers like Jonah Goldberg of the National Review, but you find concessions to it from other leftists besides Wineapple, which mostly takes the form of failing to take the charges head-on. In an interview with NPR’s “All Things Considered,” Anthony Arthur, an Upton Sinclair biographer included in Wineapple’s article, skirts around the subject of their guilt and allows the typically liberal NPR listener to assume the worst about Sacco and Vanzetti.

This was not the first documentary done on Sacco and Vanzetti. In 1971 an Italian made Docudrama was released.

Ennio Morricone received his first Nastro d'Argento in 1970 for the music in Metti una Sera a Cena (Giuseppe Patroni Griffi, 1969) and his second only a year later for Sacco e Vanzetti (Guiliano Montaldo, 1971) where he had made a memorable collaboration with the legendary American folk singer and activist Joan Baez.

An Historical Background to the Sacco-Vanzetti Case

by Paul Avrich

For one cannot deal with Sacco and Vanzetti without talking about anarchism; and, as Professor Pernicone pointed out, the greatest single shortcoming in the literature on the case-a literature that is vast, enormous-is its failure to come to grips with Sacco and Vanzetti as anarchists. Anarchism was a central feature of their lives. To write about Sacco and Vanzetti without talking about the anarchist connection, the anarchist dimension, is equivalent to writing about Eugene Victor Debs without talking about socialism, or to writing about Lenin and Trotsky without talking about communism. Anarchism was the passion, the great idea of Sacco and Vanzetti. It was the driving force of their lives. It was their obsession, their love, their chief interest on a day-to-day basis.

I'd like to read three quotations from their writings which illustrate this point. First, a quotation from Vanzetti's brief autobiography, The Story of a Proletarian L ife:

I am and will be until the last instant (unless I should discover that I am in error) an anarchist communist, because I believe that communism is the most humane form of social contract, because I know that only with liberty can man rise, become noble, and complete.

Sacco and Vanzetti

by Howard ZinnFifty years after the executions of Italian immigrants Sacco and Vanzetti, Governor Dukakis of

One letter, signed John M. Cabot, U.S. Ambassador Retired, declared his “great indignation” and pointed out that Governor Fuller’s affirmation of the death sentence was made after a special review by “three of Massachusetts’ most distinguished and respected citizens—President Lowell of Harvard, President Stratton of MIT and retired Judge Grant.”

Those three “distinguished and respected citizens” were viewed differently by Heywood Broun, who wrote in his column for the New York World immediately after the Governor’s panel made its report. He wrote:

It is not every prisoner who has a President of Harvard University throw on the switch for him….If this is a lynching, at least the fish peddler and his friend the factory hand may take unction to their souls that they will die at the hands of men in dinner jackets or academic gowns.

Heywood Broun, one of the most distinguished journalists of the twentieth century, did not last long as a columnist for the

On that 50th year after the execution, the New York Times reported that: “Plans by Mayor Beame to proclaim next Tuesday ‘Sacco and Vanzetti Day’ have been canceled in an effort to avoid controversy, a City Hall spokesman said yesterday.”

There must be good reason why a case 50-years-old, now over 75-years-old, arouses such emotion. I suggest that it is because to talk about Sacco and Vanzetti inevitably brings up matters that trouble us today: our system of justice, the relationship between war fever and civil liberties, and most troubling of all, the ideas of anarchism: the obliteration of national boundaries and therefore of war, the elimination of poverty, and the creation of a full democracy.

Michael D. Yates, "Sacco and Vanzetti"

In the spring of 1920 two Italian immigrants, Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco, were accused of the April 15 robbery of the payroll of the Slater and Morrill Shoe Factories in South Braintree, Massachusetts and the murders of the paymaster Frederick A. Parmenter and his guard Alessandro Beradelli. The accused were anarchists, followers of Luigi Galleani, a prominent Italian radical, who advocated violence against the state. At the start of the trial the Great Red Scare was in full swing, fueled by the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, the growth of radical sentiment in the United States, and the draconian laws enacted during the First World War. Immigrants, painted as anti-American radicals, bore the brunt of it, harassed, arrested, and summarily deported on the flimsiest of charges. After a spectacularly unfair trial, in which judge Webster Thayer displayed blatant bias against the defendants and prosecutor Frederick Katzman willfully violated much of the canon of legal ethics, the jury convicted Sacco and Vanzetti of murder. Between their conviction on June 14, 1921 and their execution on August 23, 1927, the case of Sacco and Vanzetti became a cause celebre in the United States and around the world.Sacco and Vanzetti

Two Immigrants Targeted For Their Beliefs

by Marlene Martin

To understand why this travesty of justice occurred, we first have to look at the hostile political climate towards immigrants and radicals. Following the First World War, the U.S. government responded to a wave of strikes and political unrest with a crackdown. The Palmer raids of the early 1920s, organized by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, resulted in thousands of radicals, especially immigrants, being rounded up, beaten, and held incommunicado for days.

It’s clear from the proceedings that Sacco and Vanzetti were convicted not because the evidence proved them guilty, but because they were anarchists and immigrants.

Dana Gioia Online - Italian-American Poetry

The first generation of Italian-American writers to work in English made their most important contributions neither in poetry nor fiction but in radical politics. Carlo Tresca and Arturo Giovannitti, for example, were both published poets, but today they are remembered for their social activism. Their political journalism, which passionately addressed the timeless concerns of equality and justice, remains more vital than their verse. Selden Rodman boldly reprinted Bartolomeo Vanzetti's last speech to the court as verse in his 1938 New Anthology of Modern Verse, and Vanzetti's proud words spoken in slightly awkward English sustain the pressure of transcription. Few poems by his Italian-American contemporaries still read so well.

Despite the stylistic diversity, one does notice certain underlying themes that unite the work of first and second generation writers. I would cite four central experiences that haunt —either overtly or subtly—the Italian-American poetic imagination. The first is poverty. The poets and their families have usually known genuine privation and penury both here and in Europe. This bitter memory informs their views of America and themselves. Their original status as economic and social outsiders in America also colors their political views. It often makes them suspicious or critical of established power. Anarchy appeals to the Southern Italian worldview. Revolution and resistance also exercise a mythic charm. Early Italian-American poets were usually political radicals, though rarely loyal and obedient members of any party. More recently, several Italian-American women—most notably Sandra Mortola Gilbert—are significant figures in the feminist movement.

WOODY GUTHRIE

BALLADS OF SACCO & VANZETTI

(Folkways), recorded 1946-'47.

IN 1945 Moses Asch commissioned balladeer Woody Guthrie -- who had already written on such themes as the Oklahoma Dust Bowl -- to go to Boston and document the story of anarchists and trade unionists Sacco and Vanzetti. The songs were recorded in January 1947 to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of their execution, and released as an album in 1960.VANZETTI'S LETTER

The year, it is 1927, an' the day is the third day of May;

Town is the city called Boston, an' our address this dark Dedham jail.

To your honor, the Governor Fuller, to the council of Massachussetts state,

We, Bartolomo [sic] Vanzetti, an' Nicola Sacco, do say:

Confined to our jail here at Dedham an' under the sentence of death,

We pray you do exercise your powers an' look at the facts of our case.

We do not ask you for a pardon, for a pardon would admit of our guilt;

Since we are both innocent workers, we have no guilt to admit.

We are both born by parents in Italy, can't speak English too well;

Our friends of labor are writin' these words, back of the barsin our cell.

Our friends say if we speak too plain, sir, we may turn your feelings away,

Widen these canyons between us, but we risk our life to talk plain.

We think, sir, that each human bein' is in close touch with all of man's kind,

We think, sir, that each human bein' knows right from the wrong in his mind.

We talk to you here as a man, sir, even knowing our opinions divide;

We didn't kill the guards at South Braintree, nor dream of such a terrible crime.

We call your eye to this fact, sir, we work with our hand and our brain;

These robberies an' killings, were done, sir, by professional bandit men,

Sacco has been a good cutter, Mrs. Sacco their money has saved;

I, Vanzetti, l could have saved money, but I gave it as fast as received.

l'm a dreamer, a speaker, an' a writer; I fight on the working folks' side.

Sacco is Boston's fastest shoe trimmer, and he talks to the husbands and wives.

We hunted your land, and we found it, hoped we'd find freedom of mind,

Built up your land, this Land of the Free, an' this is what we come to find.

If we was those killers, good Governor, we'd not be so dumb and so blind

To pass out our handbills and make workers' speeches, out here by the scene of the crime.

Those fifteen thousands of dollars the lawyers and judge said we took,

Do we, sir, dress up like two gentlemen with that much in our pocketbook?

Our names are on the long list of radicals of the Federal Government, sir,

They said that we needed watching as we peddled our literature.

Judge Thayer's mind's made up, sir, when we walked into the court;

Well, he called us anarchistic bastards, said lots of other things worse.

They brought people down there to Brockton to look through the bars of our cell,

Made us act out the motions of the killers, and still not so many could tell.

Before the trial ever started, the jury foreman did say,

An' he cussed us an' said, "Damn they, well, they'd ought to hang anyway."

Our fatal mistake was carryin' our guns, about which we had to tell lies

To keep the police from raiding the homes of workers believing like us.

A labor paper, or a picture, a letter from a radical friend,

An old cheap gun like you keep around home, would torture good women and men.

We all feared deporting and whipping, torments to make us confess

The place where the workers are meeting, the house, your name, and address.

Well. the officers said we feared something which they called a consciousness of guilt.

We was afraid of wreckin' more homes, and seein' more workers' blood spilt.

Well, the very first question they asked us was not about killing the clerks,

But things about our labor movement, and how our trade union works.

Oh, how could our jury see clearly, when the lawyers, and judges, and cops

Called us low type Italians, said we looked just like regular wops,

Draft dodgers, gun packers, anarchists, these vulgar sounding names,

Blew dust in the eyes of jurors, the crowd in the courtroom the same.

We do not believe, sir, that torture, beatings, and killings and pains

Will lift man's eyes to a highest of view an' break his bilbos and chains.

We believe that you must struggle for freedom before your freedom you'll gain,

Freedom from fear, sir, and greed, sir, and your freedom to think higher things.

This fight, sir, is not a new battle, we did not make it last night,

'Twas fought by Godwin, Shelly, Pisacane, Tolstoy and Christ;

It's bigger than the atoms an' the sands of the desert, planets that roll in the sky;

Till workers get rid of their robbers, well, it's worse, sir, to live than to die.

Your Excellency, we're not askin' pardon but askin' to be set free,

With liberty, and pride, sir, and honor, and a pardon we will not receive.

A pardon you given to criminals who've broken the laws of the land;

We don't ask you for pardon, sir, because we are innocent men.

Well, if you shake your head "no", dear Governor, of course, our doom it is sealed.

We hold up our heads like two sons of men, seven years in these cells of steel.

We walk down this corridor to death, sir, like workers have walked it before,

But we'll work in our working class struggle if we live a thousand lives more.

Sacco and Vanzetti. Produced by Curtis Fox, 1998. Part of a radio series, The Past Present: History for Public Radio. Distributed for broadcast to public radio stations in January, 1999.

Marc Blitzstein's Magnum Opus At Last

Sacco and Vanzetti

"The Sacco-Vanzetti case united the liberals," wrote David Riesman in the 1960s. "The Rosenberg case divided them."

When Marc Blitzstein began writing his magnum opus, the three-act opera, "Sacco and Vanzetti," commissioned by the Ford Foundation and optioned by the Metropolitan Opera in 1960, he was thinking of the Rosenbergs. His sister, Josephine Davis, told me that, when I first met her and looked at his unfinished works in 1970, six years after his death.

Both cases had provoked a worldwide outcry at the injustice of executing people for crimes they had not committed: robbery and murder in the 1920s case of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti; stealing the "secret" of the atom bomb in the 1950s case of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

The "good shoemaker" and the "poor fish peddler" who were executed in 1927 after a bitter, seven-year battle in court, in the press and in many minds, keep agitating American imaginations. Composer Marc Blitzstein is writing an opera about them, and an off-Broadway producer is planning a musical. This week NBC presents the second installment of its two-part Sacco-Vanzetti Story, billed as a "dramatic interpretation of the much-disputed case." Taken together, the two taped installments provide two absorbing hours, somewhat marred by overly insistent pleading.

Letters From Prison, 1921-1927

Sacco & Vanzetti Trial Homepage

Letters of Bartolomeo Vanzetti

Letters written in 1921-24 in Charlestown State Prison

Letters written in 1925 in the Bridgewater Hospital for the Criminally Insane

Letters written in 1925-April 1927 in Charlestown State Prison

Letters written in April-June 1927 in Dedham Jail

Letters written in July-August 21, 1927 from Charlestown State Prison

Letters written August 21-22, 1927 from the Death House, Massachusetts State Prison

Letters of Nicola Sacco

Letters written in 1921-June 1927 in Dedham Jail

Letters written in July-August 18, 1927 in Charlestown State Prison

Source: The Letters of Sacco and Vanzetti, edited by Marion D. Frankfurter and Gardner Jackson (1928).

The Atlantic Monthly, June 1977

The Never-Ending Wrong

For several years in the early 1920s when I was living part of the time in Mexico, on each return to New York, I would follow again the strange history of the Italian emigrants Nicola Sacco a shoemaker, and Bartolomeo Vanzetti a fishmonger, who were accused of a most brutal holdup of a payroll truck, with murder, in South Braintree, Massachusetts, in the early afternoon of April 15, 1920. They were tried before a Boston court and condemned to death about eighteen months later.

I cannot even now decide by my own evidence whether or not they were guilty of the crime for which they were put to death. They expressed in their letters many thoughts, if not always noble, at least elevated, exalted even. Their fervor and human feelings gave the glow of life to the weary stock phrases of those writing about them, and we do know now, all of us, that the most appalling cruelties are committed by apparently virtuous governments in expectation of a great good to come, never learning that the evil done now is the sure destroyer of the expected good. Yet, no matter what, it was a terrible miscarriage of justice; it was a most reprehensible abuse of legal power, in their attempt to prove that the law is something to be inflicted--not enforced--and that it is above the judgment of the people.

Sacco and Vanzetti

by Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman

[Published in The Road to Freedom (New York), Vol. 5, Aug. 1929.]

THE names of the "good shoe-maker and poor fish-peddler" have ceased to represent merely two Italian workingmen. Throughout the civilised world Sacco and Vanzetti have become a symbol, the shibboleth of Justice crushed by Might. That is the great historic significance of this twentieth century crucifixion, and truly prophetic, were the words of Vanzetti when he declared, "The last moment belongs to us--that agony is our triumph."

We hear a great deal of progress and by that people usually mean improvements of various kinds, mostly life-saving discoveries and labor-saving inventions, or reforms in the social and political life. These may or may not represent a real advance because reform is not necessarily progress.

It is an entirely false and vicious conception that civilisation consists of mechanical or political changes. Even the greatest improvements do not, in themselves, indicate real progress: they merely symbolise its results. True civilization, real progress consists in humanising mankind, in making the world a decent place to live in. From this viewpoint we are very far from being civilised, in spite of all the reforms and improvements.

True progress is a struggle against the inhumanity of our social existence, against the barbarity of dominant conceptions. In other words, progress is a spiritual struggle, a struggle to free man from his brutish inheritance, from the fear and cruelty of his primitive condition. Breaking the shackles of ignorance and superstition; liberating man from the grip of enslaving ideas and practices; driving darkness out of his mind and terror out of his heart; raising him from his abject posture to man's full stature--that is the mission of progress. Only thus does man, individually and collectively, become truly civilised and our social life more human and worth while.

This struggle marks the real history of progress. Its heroes are not the Napoleons and the Bismarcks, not the generals and politicians. Its path is lined with the unmarked graves of the Saccos and Vanzettis of humanity, dotted with the auto-da-fé, the torture chambers, the gallows and the electric chair. To those martyrs of justice and liberty we owe what little of real progress and civilization we have today.

The anniversary of our comrades' death is therefore by no means an occasion for mourning. On the contrary, we should rejoice that in this time of debasement and degradation, in the hysteria of conquest and gain, there are still MEN that dare defy the dominant spirit and raise their voices against inhumanity and reaction: That there are still men who keep the spark of reason and liberty alive and have the courage to die, and die triumphantly, for their daring.

For Sacco and Vanzetti died, as the entire world knows today, because they were Anarchists. That is to say, because they believed and preached human brotherhood and freedom. As such, they could expect neither justice nor humanity. For the Masters of Life can forgive any offense or crime but never an attempt to undermine their security on the backs of the masses. Therefore Sacco and Vanzetti had to die, notwithstanding the protests of the entire world.

Yet Vanzetti was right when he declared that his execution was his greatest triumph, for all through history it has been the martyrs of progress that have ultimately triumphed. Where are the Caesars and Torquemadas of yesterday? Who remembers the names of the judges who condemned Giordano Bruno and John Brown? The Parsons and the Ferrers, the Saccos and Vanzettis live eternal and their spirits still march on.

Let no despair enter our hearts over the graves of Sacco and Vanzetti. The duty we owe them for the crime we have committed in permitting their death is to keep their memory green and the banner of their Anarchist ideal high. And let no near-sighted pessimist confuse and confound the true facts of man's history, of his rise to greater manhood and liberty. In the long struggle from darkness to light, in the age-old fight for greater freedom and welfare, it is the rebel, the martyr who has won. Slavery has given way, absolutism is crushed, feudalism and serfdom had to go, thrones have been broken and republics established in their stead. Inevitably, the martyrs and their ideas have triumphed, in spite of gallows and electric chairs. Inevitably, the people, the masses, have been gaining on their masters, till now the very citadels of Might, Capital and the State, are being endangered. Russia has shown the direction of the further progress by its attempt to eliminate both the economic and political master. That initial experiment has failed, as all first great social revaluations require repeated efforts for their realisation. But that magnificent historic failure is like unto the martyrdom of Sacco and Vanzetti--the symbol and guarantee of ultimate triumph.

Let it be clearly remembered, however, that the failure of FIRST attempts at fundamental social change is always due to the false method of trying to establish the NEW by OLD means and practices. The NEW can conquer only by means of its own new spirit. Tyranny lives by suppression; Liberty thrives on freedom. The fatal mistake of the great Russian Revolution was that it tried to establish new forms of social and economic life on the old foundation of coercion and force. The entire development of human society has been AWAY from coercion and government, away from authority towards greater freedom and independence. In that struggle the spirit of liberty has ultimately won out. In the same direction lies further achievement. All history proves it and Russia is the most convincing recent demonstration of it. Let us then learn that lesson and be inspired to greater efforts in behalf of a new world of humanity and freedom, and may the triumphant martyrdom of Sacco and Vanzetti give us greater strength and endurance in this superb struggle.

France: July, 1929.

_______________

(This joint article reached America on the 17th of July. It is altogether too good to be left till another time. How penetrating the analysis and how apt the historical inferences! It is indeed a long time since Comrade Berkman has seen his name signed to an article in an English Anarchist paper and nearly as long since Emma Goldman has appeared as a contributor. Road to Freedom is grateful for this opportunity to bring out a joint article wherein both our immutable fighters are in such complete agreement. We hope we merit more from their powerful pens in future issues.--Ed.)

The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti,

Ben Shahn, 1931-32, Tempera on canvas

Fuller Decides - TIME

Monday, August 15, 1927

Twelve leading Paris newspapers last week devoted four times as much space to two remote Italians as to the break-up of the Geneva Naval Conference. Why? The French, as lovers of liberty, were interested in whether these two Italians were to be killed by a democracy for a crime of which they were innocent or whether they were actually guilty and had been responsible for an international campaign to defeat justice.

Eleventh Hour. These demonstrations did not aid the new Sacco-Vanzetti attorney, Arthur D. Hill, and his associate, Francis B. Sayre, son-in-law of the late Woodrow Wilson, who were making eleventh-hour appeals for a new trial in Massachusetts or Federal courts. But hope for Messrs. Sacco & Vanzetti was scant. Death loomed.

Charlestown State Prison, Mass., Tuesday, Aug. 23 -- Nicola

Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti died in the electric chair early

this morning, carrying out the sentence imposed on them for the

South Braintree murders of April 15, 1920.

Sacco marched to the death chair at 12:11 and was pronounced lifeless at 12:19.

Vanzetti entered the execution room at 12:20 and was declared dead at 12:26.

To the last they protested their innocence, and the efforts of

many who believed them guiltless proved futile, although they

fought a legal and extra legal battle unprecedented in the

history of American jurisprudence.

With them died Celestino f. Madeiros, the young Portuguese, who

won seven respites when he "confessed" that he was present at

the time of the South Braintree murder and that Sacco and

Vanzetti were not with him. He died for the murder of a bank

cashier.

And so, on the evening of August 22, 1927, more than 500 policemen in blue uniforms enforced a mile-long barricade that encircled the prison. Most carried tear gas and gas masks. Mounted horses clip-clopped on the cobblestones, firemen stood ready with hoses, machine guns peeked over the top of the prison's red granite wall, and searchlights probed the surrounding darkness. The thousands of protesters who milled against the barricade included Dorothy Parker and John Dos Passos, as well as a host of anarchists, immigrants, day laborers, and a claque of garment workers, who kept up a constant round of "Solidarity Forever." The crowd swelled, with placards reading "JUSTICE IS CRUCIFIED" swaying overhead. Militants from the Hog Carriers' Union ran at the prison gate, and mounted troopers charged the masses. Several were hurt, many more were arrested. A cheer had gone up at the appearance of Sacco's wife, who'd brought their two children, and Vanzetti's sister, who'd arrived recently from Italy. But the women -- who had bid Sacco and Vanzetti farewell a few hours earlier, then hurried to the governor's office, got down on their knees, and begged for a stay of execution -- were defeated.

February 1928

Vanzetti's Last Statement: A Record by W.G. Thompson

The following document, which is not printed to prolong an argument, has no

bearing upon the official record of the tragic case to which it forms the

natural epilogue. But in human records its extraordinary character gives it a

place unlike any other known to us. - THE EDITORS, ATLANTIC MONTHLY

Monday, August 22, 1927

Sacco and Vanzetti were in the Death House in the State Prison at Charleston.

They fully understood that they were to die immediately after midnight. Mr.

Ehrmann and I, having on their behalf exhausted every legal remedy which

seemed to us available, had retired from the active conduct of the case,

holding ourselves in readiness, however, to help their new counsel in any way

we could.

I was in New Hampshire, where a message reached me from Vanzetti that he

wanted to see me once more before he died. I immediately started for Boston

with my son, reached the prison in the late afternoon or early evening, and

was at once taken by the Warden to Vanzetti. He was in one of the three cells

in a narrow room opening immediately to the chair. In the cell nearest the

chair was Madeiros, in the middle one Sacco, and in the third I found

Vanzetti. There was a small table in his cell, and when I entered the room he

seemed to be writing. The iron bars on the front of the cell were so arranged

as to leave at one place a wider space, through which what he needed could be

handed to him. Vanzetti seemed to be expecting me; and when I entered he

rose from his table, and with his characteristic smile reached through the

space between the bars and grasped me warmly by the hand. It was intimated to

me that I might sit in a chair in front of the cell, but not nearer the bars

than a straight mark painted on the floor. This I did.

I had heard that the Governor had said that if Vanzetti would release his

counsel in the Bridgewater case from their obligation not to disclose what he

had said to them the public would be satisfied that he was guilty of that

crime, and also of the South Braintree crime. I therefore began the interview

by asking one of the two prison guards who sat at the other end of the room,

about fifteen feet from where we were, to come to the front of the cell and

listen to the questions I was about to ask Vanzetti and to his replies. I

then asked Vanzetti if he had at any time said anything to Mr. Vahey or Mr.

Graham which would warrant the inference that he was guilty of either crime.

With great emphasis and obvious sincerity he answered no. He then said what

he had often said to me before, that Messrs. Vahey and Graham were not his

personal choice, but became his lawyers at the urgent request of friends, who

raised the money to pay them. He then told me certain things about their

relations to him and about their conduct of the Bridgewater case, and what he

had in fact told them. This on the next day I recorded, but will not here

repeat.

I asked Vanzetti whether he would authorize me to waive on his behalf his

privilege so far as Vahey and Graham were concerned. He readily assented to

this, but imposed the condition that they should make whatever statement they

saw fit to make in the presence of myself or some other friend, giving his

reasons for this condition, which I also recorded.

The guard then returned to his seat.

I told Vanzetti that although my belief in his innocence had all the time

been strengthened, both by my study of the evidence and by my increasing

knowledge of his personality, yet there was a chance, however remote, that I

might be mistaken; and that I thought he ought for my sake, in this closing

hour of his life when nothing could save him, to give me his most solemn

reassurance, both with respect to himself and with respect to Sacco.

Vanzetti then told me quietly and calmly, and with a sincerity which I could

not doubt, that I need have no anxiety about this matter; that both he and

Sacco were absolutely innocent of the South Braintree crime, and that he

(Vanzetti) was equally innocent of the Bridgewater crime; that while, looking

back, he now realized more clearly than he ever had the grounds of the

suspicion against him and Sacco, he felt that no allowance had been made for

his ignorance of American points of view and habits of thought, or for his

fear as a radical and almost as an outlaw, and that in reality he was

convicted on evidence which would not have convicted him had he not been an

anarchist, so that he was in a very real sense dying for his cause. He said

it was a cause for which he was prepared to die. He said it was the cause of

the upward progress of humanity, and the elimination of force from the world.

He spoke with calmness, knowledge, and deep feeling. He said he was grateful

to me for what I had done for him. He asked to be remembered to my wife and

son. He spoke with emotion of his sister and of his family. He asked me to do

what I could to clear his name, using the words "clear my name."

I asked him if he thought it would do any good for me or any friend to see

Boda. He said he thought it would. He said he did not know Boda very well,

but believed him to be an honest man, and thought possibly he might be able

to give some evidence which would help to prove their innocence.

I then old Vanzetti that I hoped he would issue a public statement advising

his friends against retaliating by violence and reprisal. I told him that,

as I read history, the truth had little chance of prevailing when violence

was followed by counter-violence. I said that, as he well knew, I could not

subscribe to his views or to his philosophy of life; but that, on the other

hand, I could not but respect any man who consistently lived up to altruistic

principles, and was willing to give his life for them. I said that if I were

mistaken, and if his views were true, nothing could retard their acceptance

by the world more than the hate and fear that would be stirred up by violent

reprisal. Vanzetti replied that, as I must well know, he desired no personal

revenge for the cruelties inflicted upon him; but he said that, as he read

his story, every great cause for the benefit of humanity had had to fight

for its existence against entrenched power and wrong, and that for this

reason he could not give his friends such sweeping advice as I had urged. He

added that in such struggles he was strongly opposed to any injury to women

and children. He asked me to remember the cruelty of seven years of

imprisonment, with alternating hopes and fears. He reminded me of the remarks

attributed to Judge Thayer by certain witnesses, especially by Professor

Richardson, and asked me what state of mind I thought such remarks indicated.

He asked me how any candid man could believe that a judge capable of

referring to men accused before him as "anarchistic bastards" could be

impartial, and whether I thought that such refinement of cruelty as had been

practiced upon him and upon Sacco ought to go unpunished.

I replied that he well knew my own opinion of these matters, but that his

arguments seemed to me not to meet the point I had raised, which was whether

he did not prefer the prevalence of his opinions to the infliction of

punishment upon persons, however richly he might think they deserved it. This

led to a pause in the conversation.

Without directly replying to my question, Vanzetti then began to speak of the

origin, early struggles, and progress of other great movements for human

betterment. He said that all great altruistic movements originated in the

brain of some man of genius, but later became misunderstood and perverted,

both by popular ignorance and by sinister self interest. He said that all

great movements which struck at conservative standards, received opinions,

established institutions, and human selfishness were at first met with

violence and persecution. He referred to Socrates, Galileo, Giordano Bruno,

and others whose names I do not now remember, some Italian and some Russian.

He then referred to Christianity, and said that it began in simplicity and

sincerity, which were met with persecution and oppression, but that it later

passed quietly into ecclesiasticism and tyranny. I said I did not think that

the progress of Christianity had been altogether checked by convention and

ecclesiasticism, but that on the contrary it still made an appeal to

thousands of simple people, and that the essence of the appeal was the

supreme confidence shown by Jesus in the truth of His own views by forgiving,

even when on the Cross, His enemies, persecutors, and slanderers.

Now, for the first and only time in the conversation, Vanzetti showed a

feeling of personal resentment against his enemies. He spoke with eloquence

of his sufferings, and asked me whether I thought it possible that he could

forgive those who had persecuted and tortured him through seven years of

inexpressible misery. I told him he knew how deeply I sympathized with him,

and that I could not say that if I were in the same situation I should not

have the same feeling; but I said that I had asked him to reflect upon the

career of One infinitely superior to myself and to him, and upon a force

infinitely greater than the force of hate and revenge. I said that in the

long run the force to which the world would respond was the force of love and

not of hate, and that I was suggesting to him to forgive his enemies, not

for their sakes, but for his own peace of mind, and also because an example

of such forgiveness would in the end be more powerful to win adherence to his

cause or to a belief in his innocence than anything else that could be done.

There was another pause in the conversation. I arose and we stood gazing at

each other for a minute or two in silence. Vanzetti finally said that he

would think of what I had said. [See Endnote 1].

I then made a reference to the possibility of personal immortality, and said

that, although I thought I understood the difficulties of a belief in

immortality, yet I felt sure that if there was a personal immortality he

might hope to share it. This remark he received in silence.

He then returned to his discussion of the evil of the present organization of

society, saying that the essence of the wrong was the opportunity it afforded

persons who were powerful because of ability or strategic economic position

to oppress the simple-minded and idealistic among their fellow men, and that

he feared that nothing but violent resistance could ever overcome the

selfishness which was the basis of the present organization of society and

made the few willing to perpetuate a system which enabled them to exploit the

many.

I have given only the substance of this conversation, but I think I have

covered every point that was talked about and have presented a true picture

of the general tenor of Vanzetti's remarks. Throughout the conversation,

with the few exceptions I have mentioned, the thought that was uppermost

in his mind was the truth of the ideas in which he believed for the

betterment of humanity, and the chance they had of prevailing. I was

impressed by the strength of Vanzetti's mind, and by the extent of his

reading and knowledge. He did not talk like a fanatic. Although intensely

convinced of the truth of his own views, he was still able to listen with

calmness and with understanding to the expression of views with which he did

not agree. In this closing scene the impression of him which had been

gaining ground in my mind for three years was deepened and confirmed - that

he was a man of powerful mind, of unselfish disposition, of seasoned

character, and of devotion to high ideals. There was no sign of breaking

down or of terror at approaching death. At parting he gave me a firm clasp

of the hand and a steady glance, which revealed unmistakably the depth of

his feeling and the firmness of his self-control.

I then turned to Sacco, who lay upon a cot bed in the adjoining cell and

could easily have heard and undoubtedly did hear my conversation with

Vanzetti. My conversation with Sacco was very brief. He rose from his cot,

referred feelingly though in a general way to some points of disagreement

between us in the past, said he hoped that our differences of opinion had not

affected our personal relations, thanked me for what I had done for him,

showed no sign of fear, shook hands with me firmly, and bade me good-bye.

His manner also was one of absolute sincerity. It was magnanimous in him not

to refer more specifically to our previous differences of opinion, because

at the root of it all lay his conviction, often expressed to me, that all

efforts on his behalf, either in court or with public authorities, would be

useless, because no capitalistic society could afford to accord him justice.

I had taken the contrary view; but at this last meeting he did not suggest

that the result seemed to justify his view and not mine. [See Endnote 2].

Endnotes:

1. it is credibly reported that when, a few hours later, Vanzetti was about

to step into the chair, he paused, shook hands with the Warden and Deputy

Warden and the guards, thanked them for their kindness to him, and, turning

to the spectators, asked them to remember that he forgave some of his

enemies. - W.G.T.

2. I afterward talked with the prison guard to whom I have referred in this

paper. He told me that after he returned to his seat he heard all that was

said by Vanzetti and myself. The room was quiet and no other persons were

talking. I showed the guard my complete notes of the interview, including

what Vanzetti had told me about Messrs. Vahey and Graham. He read the notes

carefully and said that they corresponded entirely with his memory except

that I had omitted a remark made by Vanzetti about women and children. I

then remembered the remark and added it to my memorandum. - W.G.T.

“with his sense of peace at his fate,” wrote in a last letter to a

friend: “If it had not been for these things [his imprisonment and

imminent execution] I might have lived out my life talking at street

corners to scorning men. I might have died unmarked, unknown, a

failure. This is our career and our triumph.

Never in our full life could we hope to do such work

for tolerance, for justice,

for man’s understanding of man,

as we now do by accident.

--- That last moment belongs to us

- that agony is our triumph.”

On August 23, 1977, fifty years to the day of the executions of Sacco and Vanzetti, Michael S. Dukakis, Governor of Massachusetts, issued a proclamation that concluded with the words:

Therefore, I, Michael S. Dukakis, Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts ... hereby proclaim Tuesday, August 23, 1977, "NICOLA SACCO AND BARTOLOMEO VANZETTI MEMORIAL DAY"; and declare, further, that any stigma and disgrace should be forever removed from the names of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, from the names of their families and descendants, and so ... call upon all the people of Massachusetts to pause in their daily endeavors to reflect upon these tragic events, and draw from their historic lessons the resolve to prevent the forces of intolerance, fear, and hatred from ever again uniting to overcome the rationality, wisdom, and fairness to which our legal system aspires.

They weren't pardoned. That would have been a declaration that they had been guilty. They were --- in a manner of speaking --- apologized to.

Remember Sacco and Vanzetti

By Vera B. Weisbord

(From the magazine "La Parola del Popolo" July 1977)

WHILE President Carter preaches human rights, crusading as the leader of the whole world, a more realistic stand is taken by a lesser official, Governor Dukakis who on July 19 issued a statement that Sacco and Vanzetti did not have a fair trial. Coming fifty years after the event, even this belated acknowledgement must be considered as progressive. In the 1920s the case of Sacco and Vanzetti won world-wide support perhaps more than any other civil rights case. For the sake of newcomers on the scene we shall tell once more their tragic story.

Nicola Sacco was a man of Italian origin who worked in a shoe factory in Stoughton, Massachusetts. He had a home, a wife and a little son. Bartolomeo Vanzetti, also Italian, worked as a fish peddler in nearby Plymouth. The two men were friends. On the afternoon of April 15, 1920, it happen that a crime was committed on the streets of South Braintree, another small industrial town of the vicinity. Five bandits held up the paymaster of a shoe factory, killed him and his guard and escaped with the loot of over $15,000.

What connection did this event have with our two Italian workingmen? None, none whatever. Neither was anywhere near the scene of the crime. Both had ample proof of their alibis. Nevertheless they were arrested, thrown into jail and charged with the crime of first degree murder.

The jail doors never opened for Sacco and Vanzetti. For seven agonizing years of alternating hope and despair they waited while their defense tried every possible legal device, appeal after appeal being rejected until at last on August 22, 1927, the electric chair put an end to their martyrdom.

To explain how such an outrage could occur in this fair land of peace, justice, prosperity and above all of FREEDOM we must first look into the situation prevailing in the United States in that post World War I period.

Peter Miller: Lessons of Sacco and Vanzetti -

We'll never know if Sacco and Vanzetti committed the shoe factory murder, and the question of guilt or innocence remains politically volatile even to this day. A recent flap based on a misreading of a letter by the novelist Upton Sinclair is the most recent proof of the ongoing radioactivity of this subject. But to focus on the issue of innocence or guilt is missing the point. The more fundamental question is whether they received a fair trial, and the answer is a resounding no.

More important still is the question of what we can still learn from their story. As our country remains fixated on the threat of domestic terrorism today, we would do well to reflect on how we responded to similar threats eighty years ago. Were we really more secure as a country as a result of the unconstitutional attacks on radical movements in the 1910s and '20s? Did the judicial murder of Sacco and Vanzetti help protect us from crime and terror?

Muslims and Arabs have become the current targets of racial profiling in the name of protecting our security. Looking at history will remind us that such treatment used to be reserved for Italians, now a fully-assimilated immigrant group whose members includes two justices on the Supreme Court. Does a defendant's ethnicity or political creed continue to shape the kind of justice that we offer in this country? How often do we still think something along the lines of "damn them, they ought to hang them anyway" when considering the fate of a defendant from an unpopular ethnic group, or whose beliefs are antithetical to our own?

Sacco and Vanzetti's fate also raises unsettling questions about capital punishment. As hundreds of death penalty convictions are now being overturned due to the introduction of new evidence, can the electrocution of these two men 80 years ago remind us of the folly -- not to mention the brutality -- of killing a defendant before the truth is settled?

Perhaps the greatest lesson we can take away from the Sacco and Vanzetti case was its ability to inspire millions of people to stand up on behalf of justice and reason. As the case played itself out over seven years in the 1920s, the unfairness of Sacco and Vanzetti's treatment in the courts fueled protests not just in the United States but throughout the world. Protests erupted in Boston, New York, and dozens of American cities, as well as is Paris and London, Tokyo and Buenos Aires, numerous cities in Africa, and countless other places. Books, poems, operas, and works of art further publicized the story of the two men and their legal ordeal. Would such a movement happen today?

It has in Canada. Public outcry and protests saw Freedom and Justice

for Maher Arar. Though he still cannot get the same in America.

SEE

No comments:

Post a Comment