John Jacbi discovered Ted Kaczynski’s writing at an anarchists camp in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

THE UNABOMBER WAS AN ECO FASCIST NOT AN ANARCHIST

By John H. Richardson Photograph by Colby Katz

NEW YORK MAGAZINE INTELLIGENCER

By John H. Richardson Photograph by Colby Katz

NEW YORK MAGAZINE INTELLIGENCER

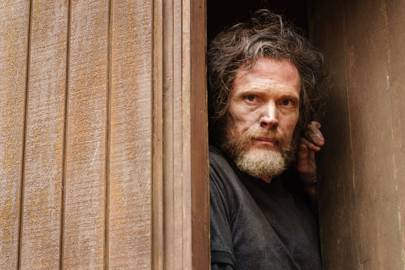

Photo: Colby Katz

When John Jacobi stepped to the altar of his Pentecostal church and the gift of tongues seized him, his mother heard prophecies — just a child and already blessed, she said. Someday, surely, her angelic blond boy would bring a light to the world, and maybe she wasn’t wrong. His quest began early. When he was 5, the Alabama child-welfare workers decided that his mother’s boyfriend — a drug dealer named Rock who had a red carpet leading to his trailer and plaster lions standing guard at the door — wasn’t providing a suitable environment for John and his sisters and little brother. Before they knew it, they were living with their father, an Army officer stationed in Fayetteville, North Carolina. But two years later, when he was posted to Iraq, the social workers shipped the kids back to Alabama, where they stayed until their mother hanged herself from a tree in the yard. John was 14. In the tumultuous years that followed, he lost his faith, wrote mournful poems, took an interest in news reports about a lively new protest movement called Occupy Wall Street, and ran away from the home of the latest relative who’d taken him in — just for a night, but that was enough. As soon as he graduated from high school, he quit his job at McDonald’s, bought some camping gear, and set out in search of a better world.

When a young American lights out for the territories in the second decade of the 21st century, where does he go? For John Jacobi, the answer was Chapel Hill, North Carolina — Occupy had gotten him interested in anarchists, and he’d heard they were active there. He was camping out with the chickens in the backyard of their communal headquarters a few months later when a crusty old anarchist with dreadlocks and a piercing gaze handed him a dog-eared book called Industrial Society and Its Future. The author was FC, whoever that was. Jacobi glanced at the first line: “The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race.”

This guy sure gets to the point, he thought. He skimmed down the paragraph. Industrial society has caused “widespread psychological suffering” and “severe damage to the natural world”? Made life more comfortable in rich countries but miserable in the Third World? That sounded right to him. He found a quiet nook and read on.

The book was written in 232 numbered sections, like an instruction manual for some immense tool. There were two main themes. First, we’ve become so dependent on technology that the real decisions about our lives are made by unseen forces like corporations and market flows. Our lives are “modified to fit the needs of this system,” and the diseases of modern life are the result: “Boredom, demoralization, low self-esteem, inferiority feelings, defeatism, depression, anxiety, guilt, frustration, hostility, spouse or child abuse, insatiable hedonism, abnormal sexual behavior, sleep disorders, eating disorders, etc.” Jacobi had experienced most of those himself.

Get unlimited access to Intelligencer and everything else New YorkLEARN MORE »

The second point was that technology’s dark momentum can’t be stopped. With each improvement, the graceful schooner that sails our shorelines becomes the hulking megatanker that takes our jobs. The car’s a blast bouncing along at the reckless speed of 20 mph, but pretty soon we’re buying insurance, producing our license and registration if we fail to obey posted signs, and cursing when one of those charming behavior-modification devices in orange envelopes shows up on our windshields. We doze off while exploring a fun new thing called social media and wake up to big data, fake news, and Total Information Awareness.

All true, Jacobi thought. Who the hell wrote this thing?

The clue arrived in section No. 96: “In order to get our message before the public with some chance of making a lasting impression, we’ve had to kill people,” the mystery author wrote.

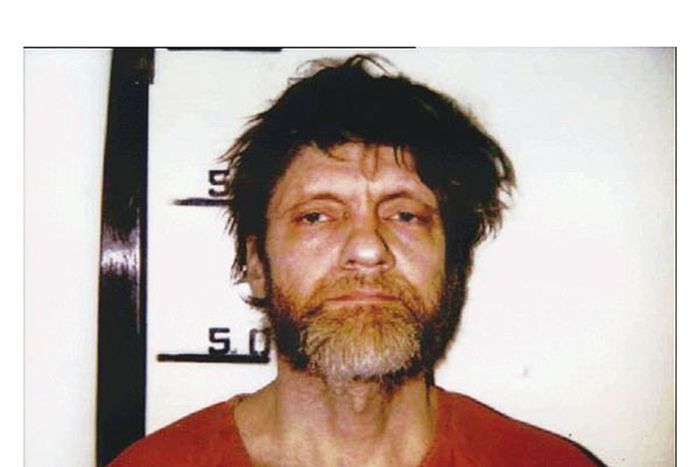

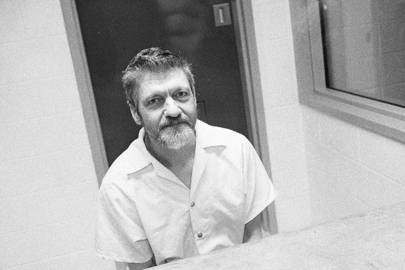

Kaczynski at the time of his arrest, in 1996. Photo: Donaldson Collection/Getty Images

“Kill people” — Jacobi realized that he was reading the words of the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, the hermit who sent mail bombs to scientists, executives, and computer experts beginning in 1978. FC stood for Freedom Club, the pseudonym Kaczynski used to take credit for his attacks. He said he’d stop if the newspapers published his manifesto, and they did, which is how he got caught, in 1995 — his brother recognized his prose style and reported him to the FBI. Jacobi flipped back to the first page, section No. 4: “We therefore advocate a revolution against the industrial system.”

The first time he read that passage, Jacobi had just nodded along. Talking about revolution was the anarchist version of praising the baby Jesus, invoked so frequently it faded into background noise. But Kaczynski meant it. He was a genius who went to Harvard at 16 and made breakthroughs in something called “boundary functions” in his 20s. He joined the mathematics department at UC Berkeley when he was 25, the youngest hire in the university’s then-99-year history. And he did try to escape the world he could no longer bear by moving to Montana. He lived in peace without electricity or running water until the day when, maddened by the invasion of cars and chain saws and people, he hiked to his favorite wild place for some relief and found a road cut through it. “You just can’t imagine how upset I was,” he told an interviewer in 1999. “From that point on, I decided that, rather than trying to acquire further wilderness skills, I would work on getting back at the system. Revenge.” In the next 17 years, he killed three people and wounded 23 more.

Jacobi didn’t know most of those details yet, but he couldn’t find any holes in Kaczynski’s logic. He said straight-out that ordinary human beings would never charge the barricades, shouting, “Destroy our way of life! Plunge us into a desperate struggle for survival!” They’d probably just stagger along, patching holes and destroying the planet, which meant “a small core of deeply committed people” would have to do the job themselves (section No. 189). Kaczynski even offered tactical advice in an essay titled “Hit Where It Hurts,” published a few years after he began his life sentence in a federal “supermax” prison in Colorado: Forget the small targets and attack critical infrastructure like electric grids and communication networks. Take down a few of those at the right time and the ripples would spread rapidly, crashing the global economic system and giving the planet a breather: No more CO2 pumped into the atmosphere, no more iPhones tracking our every move, no more robots taking our jobs.

Kaczynski was just as unsentimental about the downsides. Sure, decades or centuries after the collapse, we might crawl out of the rubble and get back to a simpler, freer way of life, without money or debt, in harmony with nature instead of trying to fight it. But before that happened, there was likely to be “great suffering” — violent clashes over resources, mass starvation, the rise of warlords. The way Kaczynski saw it, though, the longer we go like we’re going, the worse things will get. At the time his manifesto was published, many people reading it probably hadn’t heard of global warming and most certainly weren’t worried about it. Reading it in 2014 was a very different experience.

The shock that went through Jacobi in that moment — you could call it his “Kaczynski Moment” — made the idea of destroying civilization real. And if Kaczynski was right, wouldn’t he have some responsibility to do something, to sabotage one of those electric grids?

His answer was yes, which was almost as alarming as discovering an unexpected kinship with a serial killer — even when you’re sure that morality is just a social construct that keeps us docile in our shearing pens, it turns out setting off a chain of events that could kill a lot of people can raise a few qualms.

“But by then,” Jacobi says, “I was already hooked.”

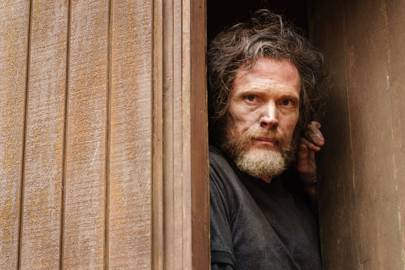

Jacobi in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Photo: Colby Katz

Quietly, often secretly, whether they gather it from the air of this anxious era or directly from the source like Jacobi did, more and more people have been having Kaczynski Moments. Books and webzines with names like Against Civilization, FeralCulture, Unsettling America, and the Ludd-Kaczynski Institute of Technology have been spreading versions of his message across social-media forums from Reddit to Facebook for at least a decade, some attracting more than 100,000 followers. They cluster around a youthful nickname, “anti-civ,” some drawing their ideas directly from Kaczynski, others from movements like deep ecology, anarchy, primitivism, and nihilism, mixing them into new strains. Although they all believe industrial civilization is in a death spiral, most aren’t trying to hurry it along. One exception is Deep Green Resistance, an activist network inspired by a 2011 book of the same name that includes contributions from one of Kaczynski’s frequent correspondents, Derrick Jensen. The group’s openly stated goal, like Kaczynski’s, is the destruction of civilization and a return to preagricultural ways of life.

So far, most of the violence has happened outside of the United States. Although the FBI declined to comment on the topic, the 2017 report on domestic terrorism by the Congressional Research Service cited just a handful of minor attacks on “symbols of Western civilization” in the past ten years, a period of relative calm most credit to Operation Backfire, the FBI crackdown on radical environmental efforts in the mid-aughts. But in Latin America and Europe, terrorist groups with florid names like Conspiracy of Cells of Fire and Wild Indomitables have been bombing government buildings and assassinating technologists for almost a decade. The most ominous example is Individualidades Tendiendo a lo Salvaje, or ITS (usually translated as Individuals Tending Toward the Wild), a loose association of terrorist groups started by Mexican Kaczynski devotees who decided that his plan to take down the system was outdated because the environment was being decimated so fast and government surveillance technology had gotten so robust. Instead, ITS would return to its guru’s old modus operandi: revenge. The group set off bombs at the National Ecology Institute in Mexico, a Federal Electricity Commission office, two banks, and a university. It now claims cells across Latin America, and in January 2017, the Chilean offshoot delivered a gift-wrapped bomb to Oscar Landerretche, the chairman of the world’s largest copper mine, who suffered minor injuries. The group explained its motives in a defiant media release: “The pretentious Landerretche deserved to die for his offenses against Earth.”

In the larger world, where no respectable person would praise Kaczynski without denouncing his crimes, little Kaczynski Moments have been popping up in the most unexpected places — the Fox News website, for example, which ran a piece by Keith Ablow called “Was the Unabomber Correct?” in 2013. After summarizing some of Kaczynski’s dark predictions about the steady erosion of individual autonomy in a world where the tools and systems that create prosperity are too complex for any normal person to understand, Ablow — Fox’s “expert on psychiatry” — came to the conclusion that Kaczynski was “precisely correct in many of his ideas” and even something of a prophet. “Watching the development of Facebook heighten the narcissism of tens of millions of people, turning them into mini reality-TV versions of themselves,” he wrote. “I would bet he knows, with even more certainty, that he was onto something.”

That same year, in the leading environmentalist journal Orion, a “recovering environmentalist” named Paul Kingsnorth — who’d stunned his fellow activists in 2008 by announcing that he’d lost hope — published an essay about the disturbing experience of reading Kaczynski’s manifesto for the first time. If he ended up agreeing with Kaczynski, “I’m worried that it may change my life,” he confessed. “Not just in the ways I’ve already changed it (getting rid of my telly, not owning a credit card, avoiding smartphones and e-readers and sat-navs, growing at least some of my own food, learning practical skills, fleeing the city, etc.) but properly, deeply.”

By 2017, Kaczynski was making inroads with the conservative intelligentsia — in the journal First Things, home base for neocons like Midge Decter and theologians like Michael Novak, deputy editor Elliot Milco described his reaction to the manifesto in an article called “Searching for Ted Kaczynski”: “What I found in the text, and in letters written by Kaczynski since his incarceration, was a man with a large number of astute (even prophetic) insights into American political life and culture. Much of his thinking would be at home in the pages of First Things.” A year later, Foreign Policy published “The Next Wave of Extremism Will Be Green,” an editorial written by Jamie Bartlett, a British journalist who tracks the anti-civ movement. He estimated that a “few thousand” Americans were already prepared to commit acts of destruction. Citing examples such as the Standing Rock pipeline protests in 2017, Bartlett wrote, “The necessary conditions for the radicalization of climate activism are all in place. Some groups are already showing signs of making the transition.”

The fear of technology seems to grow every day. Tech tycoons build bug-out estates in New Zealand, smartphone executives refuse to let their kids use smartphones, data miners find ways to hide their own data. We entertain ourselves with I Am Legend, The Road, V for Vendetta, and Avatar while our kids watch Wall-E or FernGully: The Last Rainforest. An eight-part docudrama called Manhunt: The Unabomber was a hit when it premiered on the Discovery Channel in 2017 and a “super hit” when Netflix rereleased it last summer, says Elliott Halpern, the producer Netflix commissioned to make another film focusing on Kaczynski’s “ideas and legacy.” “Obviously,” Halpern says, “he predicted a lot of stuff.”

And wouldn’t you know it, Kaczynski’s papers have become one of the most popular attractions at the University of Michigan’s Labadie Collection, an archive of original documents from movements of “social unrest.” Kaczynski’s archivist, Julie Herrada, couldn’t say much about the people who visit — the archive has a policy against characterizing its clientele — but she did offer a word in their defense. “Nobody seems crazy.”

Two years ago, I started trading letters with Kaczynski. His responses are relentlessly methodical and laced with footnotes, but he seems to have a droll side, too. “Thank you for your undated letter postmarked 6/11/18, but you wrote the address so sloppily that I’m surprised the letter reached me …” “Thank you for your letter of 8/6/18, which I received on 8/16/18. It looks like a more elaborate and better developed, but otherwise typical, example of the type of brown-nosing that journalists send to a ‘mark’ to get him to cooperate.” Questions that revealed unfamiliarity with his work were poorly received. “It seems that most big-time journalists are incapable of understanding what they read and incapable of transmitting facts accurately. They are frustrated fiction-writers, not fact-oriented people.” I tried to warm him up with samples of my brilliant prose. “Dear John, Johnny, Jack, Mr. Richardson, or whatever,” he began, before informing me that my writing reminded him of something the editor of another magazine told the social critic Paul Goodman, as recounted in Goodman’s book Growing Up Absurd: “ ‘If you mean to tell me,” an editor said to me, “that Esquire tries to have articles on serious issues and treats them in such a way that nothing can come of it, who can deny it?’ ” (Kaczynski’s characteristically scrupulous footnote adds a caveat, “Quoted from memory.”) His response to a question about his political preferences was extra dry: “It’s certainly an oversimplification to say that the struggle between left & right in America today is a struggle between the neurotics and the sociopaths (left = neurotics, right = sociopaths = criminal types),” he said, “but there is nevertheless a good deal of truth in that statement.”

But the jokes came to an abrupt stop when I asked for his take on America’s descent into immobilizing partisan warfare. “The political situation is complex and could be discussed endlessly, but for now I will only say this,” he answered. “The current political turmoil provides an environment in which a revolutionary movement should be able to gain a foothold.” He returned to the point later with more enthusiasm: “Present situation looks a lot like situation (19th century) leading up to Russian Revolution, or (pre-1911) to Chinese Revolution. You have all these different factions, mostly goofy and unrealistic, and in disagreement if not in conflict with one another, but all agreeing that the situation is intolerable and that change of the most radical kind is necessary and inevitable. To this mix add one leader of genius.”

Kaczynski was Karl Marx in modern flesh, yearning for his Lenin. In my next letter, I asked if any candidates had approached him. His answer was an impatient no — obviously any revolutionary stupid enough to write to him would be too stupid to lead a revolution. “Wait, I just thought of an exception: John Jacobi. But he’s a screwball — bad judgment — unreliable — a problem rather than a help.”

The Kaczynski moment dislocates. Suddenly, everyone seems to be living in a dream world. Why are they talking about binge TV and the latest political outrage when we’re turning the goddamn atmosphere into a vast tanker of Zyklon B? Was he right? Were we all gelded and put in harnesses without even knowing it? Is this just a simulation of life, not life itself?

People have moments like that under normal conditions, of course. Sigmund Freud wrote a famous essay about them way back in 1929, Civilization and Its Discontents. A few unsettled souls will always quit that bank job and sail to Tahiti, and the stoic middle will always suck it up. But Jacobi couldn’t accept those options. Staggered by the shock of his Kaczynski Moment but intent on rising to the challenge, he began corresponding with the great man himself, hitchhiked the 644 miles from Chapel Hill to Ann Arbor to read the Kaczynski archives, tracked down his followers all around the world, and collected an impressive (and potentially incriminating) cache of material on ITS along the way. He even published essays about them in an alarmingly terror-friendly print journal named Atassa. But his biggest influence was a mysterious Spanish radical theorist known only by the pseudonym he used to translate Kaczynski’s manifesto into Spanish, Último Reducto. Recommended by Kaczynski himself, who even supplied an email address, Reducto gave Jacobi a daunting reading list and some editorial advice on his early essays, which inspired another series of TV-movie twists in Jacobi’s turbulent life. Frustrated by the limits of his knowledge, he applied to the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, to study some more, received a full scholarship and a small stipend, and buckled down for two years of intense scholarship. Then he quit and hit the road again. “I think the homeless are a better model than ecologically minded university students,” he told me. “They’re already living outside of the structures of society.”

Four years into this bizarre pilgrimage, Jacobi is something of an underground figure himself — the ubiquitous, eccentric, freakishly intellectual kid who became the Zelig of ecoextremism. Right now, he’s about to skin his first rat. Barefoot and shirtless, with an old wool blanket draped over his shoulders, long sun-streaked hair and gleaming blue eyes, he hurries down a rocky mountain trail toward a stone-age village of wattle-and-daub huts, softening his voice to finish his thought. “Ted was a good start. But Ted is not the endgame.”

He stops there. The village ahead is the home of a “primitive skills” school called Wild Roots. Blissfully untainted by modern conveniences like indoor toilets and hot showers, it’s also free of charge. It has just three rules, and only one that will get us kicked out. “I don’t want to be associated with that name,” Wild Roots’ de facto leader told us when I mentioned Kaczynski. “I don’t want my name associated with that name,” he added. “I really don’t want to be associated with that name.”

Jacobi arrives at the open-air workshop, covered by a tin roof, where the dirtiest Americans I’ve ever seen are learning how to weave cordage from bark, start friction fires, skin animals. The only surprise is the lives they led before: a computer analyst for a military-intelligence contractor, a Ph.D. candidate in engineering, a classical violinist, two schoolteachers, and a rotating cast of college students the older members call the “pre-postapocalypse generation.” Before he became the community blacksmith, the engineering student was testing batteries for ecofriendly cars. “It was a fucking hoax,” he says now. “It wasn’t going to make any difference.” At his coal-fired forge, pounding out simple tools with a hammer and anvil, he feels much more useful. “I can’t make my own axes yet, but I made most of the handles on those tools, I make all my own punches and chisels. I made an adze. I can make knives.”

Freshly killed this morning, five dead rats lie on a pine board. They’re for practice before trying to skin larger game. Jacobi bends down for a closer look, selects a rat, ties a string to its twiggy leg, and hangs it from a rafter. He picks up a razor. “You wanna leave the cartilage in the ear,” his teacher says. “Then cut just above the white line and you’ll get the eyes off.”

A few feet away, a young woman who fled an elite women’s college in Boston pounds a wooden staff into a bucket to pulverize hemlock bark to make tannin to tan the bear hide she has soaking in the stream — a mixture of mashed hemlock and brain tissue is best, she says, though eggs can substitute if you can’t get fresh brain.

Jacobi works the razor carefully. The eyes fall into the dirt.

“I’m surprised you haven’t skinned a rat before,” I say.

“Yeah, me too,” he replies.

He is, after all, the founder of The Wildernist and Hunter/Gatherer, two of the more radical web journals in the personal “rewilding” movement. The moderates at places like ReWild University talk of “rewilding your taste buds” and getting in “rockin’ fit shape.” “We don’t have to demonize our culture or attempt to hide from it,” ReWild University’s website enthuses. Jacobi has no interest in padding the walls of the cage — as he put it in an essay titled “Taking Rewilding Seriously,” “You can’t rewild an animal in a zoo.”

He’s not an idiot; he knows the zoo is pretty much everywhere at this point. He explained this in the philosophical book he wrote at 22, Repent to the Primitive: “My focus on the Hunter/Gatherer is based on a tradition in political philosophy that considers the natural state of man before moving on to an analysis of the civilized state of man. This is the tradition of Hobbes, Rousseau, Locke, Hume, Paine.” His plan is to ace his primitive skills, then test living wild for an extended time in the deepest forest he can find.

So why did it take him so long to get out of the zoo?

“I thought sabotage was more important,” he says.

But this isn’t the place to talk about that — he doesn’t want to break Wild Roots’ rules. Jacobi goes silent and works his razor down the rat’s body, pulling the skin down like a sock.

When he’s finished, he leads the way back into the woods, naming the plants: pokeberry, sourwood, rhododendron, dog hobble, tulip poplar, hemlock. The one with orange flowers is a lily that will garnish his dinner tonight. “If you want, I can get some for you,” he offers.

Then he returns to the forbidden topic. “I could never do anything like that,” he says firmly — unless he could, which is also a possibility. “I don’t have any moral qualms with violence,” he says. “I would go to jail, but for what?”

For what? The first time I talked to him, he told me he had dreams of being the leader Kaczynski wanted.

“I am being a little evasive,” he admits. His other reason for going to college, he says, was to plant the anti-civ seed in the future lawyers and scientists gathered there — “people who will defend you, people who have access to computer networks” — and also, speaking purely speculatively, who could serve as “the material for a terrorist criminal network.”

“Did you convince anybody?” I ask.

“I don’t know. I always told them not to tell me.”

“So you wanted to be the Lenin?”

“Yeah, I wanted to be Lenin.”

But let’s face it, he says, the revolution’s never going to happen. Probably. Maybe. That’s why he’s heading into the woods. “I want to come out in a few years and be like Jesus,” he jokes, “working miracles with plants.”

Isn’t he doing exactly what Lenin did during his exile in Europe, though? Honing his message, building a network, weighing tactical options, and creating a mystique. Is he practicing “security culture,” the activist term for covering your tracks? “Are you hiding the truth? Are you secretly plotting with your hard-core cadre?”

He smiles. “I wouldn’t be a very good revolutionary if I told you I was doing that.”

At the last minute, Abe Cabrera changed our rendezvous point from a restaurant in New Orleans to an alligator-filled swamp an hour away. This wasn’t a surprise. Jacobi had given me Cabrera’s email address, identifying him as the North American contact for ITS, which Cabrera immediately denied. His interest in ITS was purely academic, he insisted, an outgrowth of his studies in liberation theology. “However,” he added, “to say that I don’t have any contact with them may or may not be true.”

Now he’s leading me into the swamp, literally, talking about an ITS bomb attack on the head of the Department of Physical and Mathematical Sciences at the University of Chile in 2011. “Is that a fair target?” he asks. “For Uncle Ted, it would have been, so I guess that’s the standard.” He chuckles.

He’s short, round, bald, full of nervous energy, wild theories, and awkward tics — if “Terrorist Spokesman” doesn’t work out for him, he’s a shoo-in for “Mad Scientist in a B-Movie.” Giant ferns and carpets of moss appear and disappear as he leads the way into the swamp, where the elephantine roots of cypress trees stand in the eerie stillness of the water like dinosaurs.

He started checking out ITS after he heard some rumors about a new cell starting up in Torreón, his grandparents’ birthplace in Mexico, he says, but the group didn’t really catch his interest until it changed its name from Individuals Tending Toward the Wild to Wild Reaction. Why? Because healthy animals don’t have “tendencies” when they confront an enemy. As one Wild Reaction member put it in the inevitable postattack communiqué, another example of the purple prose poetry that has become the group’s signature: “I place the device, and it transforms me into a coyote thirsting for revenge.”

Cabrera calls this “radical animism,” a phrase that conjures the specter of nature itself rising up in revolt. Somehow that notion wove together all the dizzying twists his life had taken — the years as the child of migrant laborers in the vegetable fields of California’s Imperial Valley, his flirtation with “super-duper Marxism” at UC Berkeley, the leap of faith that put him in an “ultraconservative, ultra-Catholic” order, and the loss of faith that surprised him at the birth of his child. “Most people say, ‘I held my kid for the first time and I realized God exists.’ I held my kid the first time and I said, ‘You know what? God is bullshit.’ ” People were great in small doses but deadly in large ones, even the beautiful little girl cradled in his arms. There were no fundamental ethical values. It all came down to numbers. If that was God’s plan, the whole thing was about as spiritually “meaningful as a marshmallow,” Cabrera says.

John Jacobi is a big part of this story, he adds. They connected on Facebook after a search for examples of radical animism led him to Hunter/Gatherer. They both contributed to the journal Atassa, which was dedicated on the first page to the premise that “civilization should be fought” and that the example of Ted Kaczynski “is what that fighting looks like.” In the premier edition, Jacobi made the prudent decision to write in a detached tone. Cabrera’s essay bogs down in turgid scholarship before breaking free with a flourish of suspiciously familiar prose poetry: “Ecoextremists believe that this world is garbage. They understand progress as industrial slavery, and they fight like cornered wild animals since they know that there is no escape.”

Cabrera weaves in and out of corners like a prisoner looking for an escape route, so it’s hard to know why he chose a magazine reporter for his most incendiary confession: “Here’s the super-official version I haven’t told anybody — I am the unofficial voice-slash-theoretician of ecoextremism. I translated all 30 communiqués. I translated one last night.”

Abe Cabrera: Abracadabra.

Yes, he knows this puts him dangerously close to violating the laws against material contributions to terrorism. He read the Patriot Act. That’s why he leads a double life, even a triple life. Nobody at work knows, nobody from his past knows, even his wife doesn’t know. He certainly doesn’t want his kids to know. He doesn’t even want to tell them about climate change. Math homework, piano lessons, gymnastics, he’s “knee-deep in all that stuff.” He punches the clock. “What else am I gonna do? I love my kids,” he says. “I hope for their future, even though they have no future.”

His mood sinks, reminding me of Jacobi. Shifts in perspective seem to be part of this world. Puma hunted here before the Europeans came, Cabrera says, staring into the swamp. Bears and alligators, too, things that could kill you. The cypress used to be three times as thick. When you look around, you see how much everything has suffered.

But we’re not in this mess because of greed or nihilism; we’re in it because we love our children so much we made too many of them. And we’re just so good at dominating things, all that is left is to lash out in a “wild reaction,” Cabrera says. That’s why he sympathizes with ITS. “It’s like, ‘Be the psychopathic destruction you want to see in the world’, ” he says, tossing out one last mordant chuckle in place of a good-bye.

Kaczynski is annoyed with me. “Do not write me anything more about ITS,” he said. “You could get me in trouble that way.” He went on: “What is bad about an article like the one I expect you to write is that it may help make the anti-tech movement into another part of the spectacle (along with Trump, the ‘metoo movement,’ neo-Nazis, antifa, etc.) that keeps people entertained and therefore thoughtless.”

ITS, he says, is the very reason he cut Jacobi off. Even after Kaczynski told him the warden was dying for a reason to reduce his contacts with the outside world, the kid kept sending him news about them. He ended his letter to me with a controlled burst of fury. “A hypothesis: ITS is instigated by some country’s security services — probably Mexico. Their real task is to spread hopelessness, because where there is no hope there is no serious resistance.”

Wait … Ted Kaczynski is hopeful? The Ted Kaczynski who wants to destroy civilization? The idea seems ridiculous right up to the moment it spins around and becomes reasonable. What better evidence could you find than the unceasing stream of tactical and strategic advice that he’s sent from his prison cell for almost 20 years, after all. He’s hopeful that civilization can be taken down in time to save some of the planet. I guess I just couldn’t imagine how anyone could ever manage to rally a group of ecorevolutionaries large enough to do the job.

“If you’ve read my Anti-Tech Revolution, then you haven’t understood it,” he scolds. “All you have to do is disable some key components of the system so that the whole thing collapses.” I do remember the “small core of deeply committed people” and “Hit Where It Hurts,” but it’s still hard to fathom. “How long does it take to do that?” Kaczynski demands. “A year? A month? A week?”

On paper, Deep Green Resistance meets most of his requirements. The original core group spent five years holding conferences and private meetings to hone its message and build consensus, then publicized it effectively with its book, which speculates about tactical alternatives to stop the “planet from burning to a cinder”: “If selective disruption doesn’t work soon enough, some resisters may conclude that all-out disruption is needed” and launch “coordinated actions on a large scale” against key targets. DGR now has as many as 200,000 members, according to the group’s co-founder — a soft-spoken 30-year-old named Max Wilbert — who could shave off his Mephistophelian goatee and disappear into any crowd. Two hundred thousand may not sound like much when Beyoncé has 1 million-plus Instagram followers, but it’s not shabby in a world where lovers cry out pseudonyms during sex. And Fidel had only 19 in the jungles of Cuba, as Kaczynski likes to point out.

Jacobi says DGR was hobbled by a doctrinal war over “TERFs,” an acronym I had to look up — it’s short for “trans-exclusionary radical feminists” — so this summer they’re rallying the troops with a crash course in “resistance training” at a private retreat outside Yellowstone National Park in Montana. “This training is aimed at activists who are tired of ineffective actions,” the promotional flyer says. “Topics will include hard and soft blockades, hit-and-run tactics, police interactions, legal repercussions, operational security, terrain advantages and more.”

At the Avis counter at the Bozeman airport, my phone dings. It’s an email from the organizers of the event, saying a guy named Matt needs a ride. I find him standing by the curb. He’s in his early 30s, dressed in conventional clothes, short hair, no visible tattoos, the kind of person you’d send to check out a visitor from the media. When we get on the road and have a chance to talk, he says he’s a middle-school social-studies teacher. He’s sympathetic to the urge to escalate, but he’d prefer to destroy civilization by nonviolent means, possibly by “decoupling” from the modern world, town by town and state by state.

But if that’s true, why is he here?

“See for yourself,” he said.

We reach the camp in the late afternoon and set up our tents next to a big yurt. A mountain rises behind us, another mountain stands ahead; a narrow lake fills the canyon between them as the famous Big Sky, blushing at the advances of the night, justifies its association with the sublime. “Nature is the only place where you feel awe,” Jacobi told me after the leaves rustled at Wild Roots, and right now it feels true.

An hour later, the group gathers in the yurt outfitted with a plywood floor, sofas, and folding chairs: one student activist from UC Irvine, two Native American veterans of the Standing Rock pipeline protests, three radical lawyers, a shy working-class kid from Mississippi, a former abortion-clinic volunteer, and a few people who didn’t want to be identified or quoted in any way. The session starts with a warning about loose lips and a lecture on DGR’s “nonnegotiable guidelines” for men — hold back, listen, agree or disagree respectfully, avoid male-centered words, and follow the lead of women.

By that time, I’d already committed my first microaggression. The cook asked why I was standing in the kitchen doorway, and I answered, “Just supervising.” Her sex had nothing to do with it, I swear — I was waiting to wash my hands and, frankly, her question seemed a bit hostile. But the woman who followed me out the door to dress me down said that refusing to accept her criticism was another microaggression.

The first speaker turns the mood around. His name is Sakej Ward, and he did a tour in Afghanistan with the U.S. Joint Airborne and a few years in the Canadian military. He’s also a full-blooded member of the Wolf Clan of British Columbia and the Mi’kmaq of northern Maine with two degrees in political science, impressive muscles bulging through a T-shirt from some karate club, and one of those flat, wide Mohawks you see on outlaw bikers.

Unfortunately, he put his entire presentation off the record, so all I can tell you is that the theme was Native American warrior societies. Later he tells me the societies died out with the buffalo and the open range. They revived sporadically in the last quarter of the 20th century, but returned in earnest at events like Standing Rock. “It’s a question of ‘Are they there yet?’ We’ve been fighting this war for 500 years. But climate change is creating an atmosphere where it can happen.”

For the next two days, we get training in computer security and old activist techniques like using “lockboxes” to chain yourself to bulldozers and fences — given almost apologetically, like a class in 1950s home cooking. In another session, Ward takes us to a field and lines us up single file. Imagine you’re on a military patrol, he says, turning his back and holding his left hand out to the side, elbow at 90 degrees and palm forward. “Freeze!,” he barks.

We freeze.

“That’s the best way to conceal yourself from the enemy,” he tells us. He runs through basic Army-patrol semiotics. For “enemy,” you make a pistol with your hand and turn it thumbs-down. “Danger area” is a diagonal slash. After showing us a dozen signs, he stops. “Why am I making all the signs with my left hand?”

No one knows.

He turns around to face us with his finger pointed down the barrel of an invisible gun. “Because you always have to have a finger in control of your weapon,” he says.

The trainees are pumped afterward. “You can take out transformers with a .50 caliber,” one man says.

“But you don’t just want to do one,” says another. “You want four-man teams taking out ten transformers. That would bring the whole system to a halt.”

Kaczynski would be fairly pleased with this so far, I think. Ward is certainly a plausible contender for the Lenin role. Wilbert might be too. “We talk about ‘cascading catastrophic effects,’ ” he tells us in one of the last yurt meetings, summing up DGR’s grand strategy. “A large percent of the nation’s oil supply is processed in a facility in Louisiana, for example. If that was taken down, it would have cascading effects all over the world.”

But then the DGR women called us together for a lecture on patriarchy, which has to be destroyed at the same time as civilization. Also, men who voluntarily assume gendered aspects of female identity should never be allowed in female-sovereign spaces — and don’t call them TERFs unless you want a speech on microaggression.

Matt listens from the fringes in a hoodie and mirrored glasses, looking exactly like the famous police sketch of the Unabomber. I’m pretty sure he’s trolling them. Maybe he’s remembering the same Kaczynski quote I am: “Take measures to exclude all leftists, as well as the assorted neurotics, lazies, incompetents, charlatans, and persons deficient in self-control who are drawn to resistance movements in America today.”

At the farewell dinner, one of the more mysterious trainees finally speaks up. With long, wild hair, a floppy wilderness hat, pants tucked into waterproof boots, a wary expression, and an actual hermit’s cabin in Montana, he projects the anti-civ vibe with impressive authenticity. He was involved in some risky stuff during the Cove Mallard logging protests in Idaho in the mid-1990s, he says, but he retreated after the FBI brought him in for questioning. Lately, though, he’s been getting the feeling that things are starting to change, and now he’s sure of it. “I’ve been in a coma for 20 years,” he says. “I want to thank you guys for being here when I woke up.” One of the radical lawyers wraps up with a lyrical tribute to the leaders of Ireland’s legendary 1916 rebellion. He waxes about Thomas MacDonagh, the schoolteacher who led the Dublin brigade and whistled as he was led to the firing squad.

On the drive back to the airport, I ask Matt if he’s really a middle-school teacher. He answers with a question: What is your real interest in this thing?

I mention John Jacobi. “I know him,” he says. “We’ve traded a few emails.”

Of course he does. He’s another serious young man with gears turning behind his eyes.

“Can you imagine actually doing something like that?” I ask.

“Well,” he answers, drawing out the pause, “Thomas MacDonagh was a schoolteacher.”

The next time I talk to John Jacobi, he’s back in Chapel Hill living with a friend and feeling shaky. Things were getting strange at Wild Roots, he says — nobody could cooperate, there were personal conflicts. And, well, there was an incident with molly. It’s been a hard four years. First he lost Jesus and anarchy. Then Kaczynski and Último Reducto dumped him, which was really painful, though he understood why. “I’ve been unreliable,” he says woefully. To make matters worse, an ITS member called Los Hijos del Mencho denounced him by name online: The trouble with Jacobi was his “reluctance to support indiscriminate attacks” because of his sentimental attachment to humanity.

Jacobi is considering the possibility that his troubled past may have affected his judgment. He still believes in the revolution, he says, but he’s not sure what he’d do if somebody gave him a magic bottle of Civ-Away. He’d probably use it. Or maybe not.

I check in a couple of weeks later. He’s working in a fish store and thinking of going back to school. Maybe he can get a job in forest conservation. He’d like to have a kid someday.

He brings up Paul Kingsnorth, the “recovering environmentalist” who got rattled by Kaczynski’s manifesto in 2012. Kingsnorth’s answer to our global existential crisis was mourning, reflection, and the search for “the hope beyond hope.” The group he co-founded to help people with that task, a mixture of therapy group and think tank called Dark Mountain, now has more than 50 chapters worldwide. “I’m coming to terms with the fact that it might very well be true that there’s not much you can do,” Jacobi says, “but I’m having a real hard time just letting go with a hopeless sigh.”

In his Kaczynski essay, Kingsnorth, who has since moved to Ireland to homeschool his kids and write novels, put his finger on the problem. It was the hidden side effect of the Kaczynski Moment: paralysis. “I am still embedded, at least partly because I can’t work out where to jump, or what to land on, or whether you can ever get away by jumping, or simply because I’m frightened to close my eyes and walk over the edge.” To the people who end up in that suspended state now and then, lying in bed at four in the morning imagining the worst, here’s Kingsnorth’s advice: “You can’t think about it every day. I don’t. You’ll go mad!”

It’s winter now and Jacobi’s back on the road, sleeping in bushes and scavenging for food, looking for his place to land. Sometimes I wonder if he makes these journeys into the forest because of the way his mother ended her life — maybe he’s searching for the wild beasts and ministering angels she heard when he fell to his knees and spoke the language of God. Psychologists call that magical thinking. Medication and counseling are more effective treatments for trauma, they say. But maybe the dream of magic is the magic, the dream that makes the dream come true, and maybe grief is a gift too, a check on our human arrogance. Doesn’t every crisis summon the healers it needs?

In the poems Jacobi wrote after his mother hanged herself, she turned into a tree and sprouted leaves.

*This article appears in the December 10, 2018, issue of New York Magazine.

Inside the Unabomber's odd and furious online revival

A TV drama has rekindled interest in anti-technology terrorist Ted Kaczynski, also known as the Unabomber. Ironically enough, his followers now congregate online

THE UNABOMBER WAS AN ECO FASCIST NOT AN ANARCHIST

By JAKE HANRAHAN WIRED Wednesday 1 August 2018

The TV series Manhunt: Unabomber premiered on the Discovery Channel in the US before being picked up by Netflix for global distribution Tina Rowden/Discovery Communications

In 1978 Ted Kaczynski began building letter bombs designed to kill. They were made out of smokeless powder, match heads, nails, potassium nitrate, razor blades, and various other caustic substances. Kaczynski, a former academic and an alumnus of Harvard University, killed three people with these bombs and injured 23 others. His targets were airliners, university professors, and academics. Some of the bombs missed their targets and blew shrapnel into the bodies of postal workers and receptionists. The attacks were unscrupulous and vicious.

Kaczynski, dubbed the Unabomber by the FBI and the media, evaded capture for almost 18 years. He’d been hiding out in a self-contained wood cabin in the forests of Montana, writing a manifesto under the pseudonym “Freedom Club” (or FC) on a portable typewriter. After releasing his 35,000 word manifesto titled “Industrial Society and its Future” to the media in 1995, it became apparent that Kaczynski was fighting, in his mind at least, against the rise of technology and the perceived sickness it had infected the world with. The Unabomber was a militant neo-luddite.

Twenty-two years after Kaczynski’s bombing campaign and imprisonment, he now has a new following. Ironically enough, they all congregate on the internet.

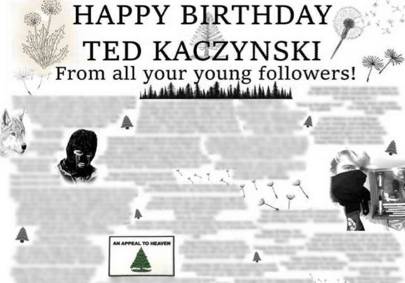

Often characterised by putting pine tree emojis in their names on social media, the new Kaczynski inspired community of self-defined primitivists and neo-luddites is flourishing. They spend hours sharing memes that call for the destruction of modern civilisation, and discuss fringe politics in Twitter group chats or on messaging app Discord. This year they even sent Kaczynski a birthday card. On the face of it, Kaczynski’s new followers are angry, bored, and sick of the modern world.

By CHARLIE WINTER AND AMARNATH AMARASINGAM

It’s all been growing rapidly since a TV drama series called Manhunt: Unabomber aired in August 2017. The series tells a fictionalised version of the Unabomber investigation. In the process of catching the elusive felon, the main character, Agent Fitz, pores over Kaczynski’s manifesto until he develops an affinity with it. He comes to the conclusion that while the brutal bombing campaign was wrong, Kaczynski’s theories were actually right. The detective ends up moving into a log cabin in the woods. Kaczynski ends up moving into prison with eight life sentences.

Large parts of the series are factually inaccurate – for example the portrayal of Kaczynski as some kind of CIA experiment gone wrong, and the insinuation that he was mentally ill — but, overall, Manhunt: Unabomber seems to have provided an easily consumable entryway to Kaczynski’s politics for the pine tree community.

Like Agent Fitz in Manhunt, the new Kaczynski followers are drawn to his theories. In this sense, there is somewhat of a Freedom Club revival happening — hundreds of young men seeking to reconnect with nature, as an act of rebellion against the state of Western civilisation, all couched in Ted Kaczynski’s anti-tech ideas.

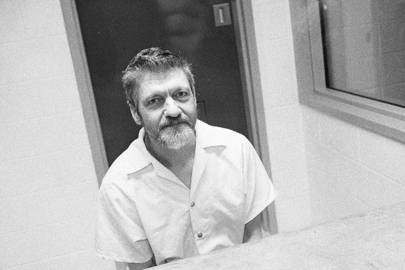

Terrorist Ted Kaczynski, aka the Unabomber, sits for an interview in a visiting room at the Federal ADX Supermax prison in Florence, Colorado in August 1999

Stephen J. Dubner/Getty Images

For a year now I’ve been chatting with various members of the pine tree community. They’re a mixed bag: some seem to actually want the total destruction of modern civilisation, and long for some kind of apocalyptic future; some are sick of the mainstream’s political correctness; some are, of course, just shit-posting. But all of them are disgusted with modernity. In an age of hyper-consumerism and ecological destruction, the pine trees don’t see a place for themselves anywhere within the current system. They long for something radical. “Modernity crushes your soul,” says Regi, who’s been part of the pine tree community from the beginning. “We see our jobs as soul crushing. Modern life is safe and boring and lacking cohesion. Many strive for a more simple and practical existence.”

But war and conflict are a constant presence on pine trees' timelines. They spread their message through tweeting things like “SHUT THE FUCK UP URBANITE!” at tech-bros, “normies”, or basically anyone who doesn’t agree with them. Instead of engaging others in public debate, they’d rather trash them. They don’t want allies. And the aesthetics of war plays a big part too. Photos of the Provisional IRA, the EZLN, and even Russian-backed separatists in east Ukraine are often posted alongside joking messages such as “I wish that were me”. One user, Ecoretard, recently tweeted: “Can I get [an] urban conflict with a faction I support so I can die for something I believe in?”

The glorification of war is perhaps another way of expressing their frustration at feeling trapped. As Regi says, “Modern life is safe and boring”. War, or at least the glorification of it, is not.

In September 1995, The Washington Post published Kaczynski's unedited, 35,000 word manifesto at the request of the US attorney general and the FBI in the hopes of ending his 17-year bombing campaign Evan Agostini/Liaison

Now, this community of Kaczynski adherents, misfits, and so-called political extremists, is less a cohesive movement than a loosely connected online subculture. For a while though, there was a pine tree leader of sorts. He was less concerned with the shit-posting and more seriously occupied with the Kaczynski worldview. His name is Rin. He wanted to build an “organisation” of “dedicated people”. He indexed Kaczynski’s prison letters, memorised paragraph numbers of the manifesto, and corralled the first new wave of Kaczynskites into a community. Rin, 24, also ran the most extensive online Kaczynski archive that has probably ever existed. That is until he pulled it all down in disgust last month.

“I decided to dedicate myself to the Ted Kaczynski project because everyone was talking about the Unabomber, but nobody was talking about Ted Kaczynski’s ideas,” Rin says.

Rin has been involved in post-leftist and green-anarchist politics since he was 18. He lives in “a Spanish speaking country”, considers himself a neo-luddite, and tries to follow the teachings of Kaczynski wherever possible. I’ve spent a lot of time in the last six months debating Rin and discussing his radical ideology with him. He’s intelligent and well-read. Despite his preoccupation with Kaczynski, I never got the impression that Rin is actually dangerous, although he can most definitely be considered a Kaczynski sympathiser. He used to run three different Twitter accounts, two of which were the Ted Kaczynski Archive and Ted Was Right. Kaczynski’s victims are never a focus of his discussion and simply shrugged off as a consequence of war.

When Rin noticed the emergence of a small online community of young men interested in all things Unabomber at the start of 2018, he began to round them up. He formed a group chat on Twitter and a radical book club where he would suggest new political literature for the pine trees. He and the rest of them embraced edgy irony and warlike aesthetics as a means to draw the youth in further. It was all very deliberate.

“Manhunt: Unabomber was the perfect breeding ground to introduce the ideology to suitable people,” Rin says. “The people attracted to the ideas began interacting with each other and formed themselves [into] a social base. They were able to form a community and slowly develop a culture. This is what eventually became Prim Twitter [Primitivist Twitter being another name for the pine tree community].”

Whilst the pine tree members were from a variety of different political milieus, they were all united by Rin under a popular front that “embraced collapse” and “loved nature”.

But Rin’s place at the head of the community didn’t last. His own creation began to morph into something unforgivably ugly, when some members began drifting from edgy luddite memes and the embrace of wild nature, to outright far-right ideologies. “Some in the community began flirting with fascism,” Rin says. “And not the left-wing type where everything they dislike is labelled ‘fascism’ — but actual genuine fascism. That was the final drop in the bucket for me. Totalitarian ideologies like fascism and communism are something I'm extremely hostile against.”

Rin is quick to emphasise that despite many on the left considering Kaczynski a fascist (mostly due to the fact he attacked them constantly in his manifesto), he actually describes fascism as “kook ideology” (“page 150 of his book Technological Slavery!”) and says Nazi ideology is “evil” in one of his letters. Rin also points out that Kaczynski has never tried to align himself with fascists, he was in favour of radical black liberation groups, and always saw green anarchist types as his natural comrades. This doesn’t change the fact that many fascist groups today use Kaczynski as an icon. Even Atomwaffen Division, the esoteric neo-Nazi militant group in the US, have made graphics using his face.

A birthday card the Pine Tree Community sent to Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber. Their words have been blurred Pine Trees

Some of the pine tree community are now splintering off into different groups, deviating from Kaczynski’s work to that of Pentti Linkola, who is a self-described eco-fascist. This coincides with new ecologically-focused Neo-Nazi groups that are now cropping up. Green fringe politics is all very much in vogue on the internet, as is the resurgence of neo-fascism. The two are starting to merge.

Rin scrapped his online Kaczynski archive in June due to the creep of fascism amongst the pine trees. But he still believes that a new generation of neo-luddism is coming.

“There is very much an interest in Ted Kaczynski growing deep down,” he says. “It's in its infancy, but it seems Ted being in prison has finally paid off. He’s gotten some extremely dedicated neo-luddites ready to contribute to the collapse of technological society.”

Rin may sound militant, but the likelihood of a major neo-luddite terror attack remains pretty low. The Freedom Club revival is still mostly spreading via memes online, not via letter bombs. The idea that our interaction with technology has reached a crisis point, is spreading further than the pine tree fringe ideology though. This year the theme has been featured often in the press. Even Silicon Valley, which made tech junkies out of us all, is having a twinge of guilt. Some reformed tech-bros have created “humane tech” organisations such as the Time Well Spent movement, founded by former Google employee Tristan Harris.

The pine tree community is a radical response to what writer Grafton Tanner once called “the mall”: a digital hellscape where people are nostalgic for something that never existed, constantly “doped on consumer goods, energy drinks, and Apple products.”

In Rin’s opinion, it’s all falling down already. “Our technological civilisation is complex and unsustainable. Its breakdown is inevitable," he says. "It will be slow and boring, but technological civilisation has already signed its death warrant.”

When John Jacobi stepped to the altar of his Pentecostal church and the gift of tongues seized him, his mother heard prophecies — just a child and already blessed, she said. Someday, surely, her angelic blond boy would bring a light to the world, and maybe she wasn’t wrong. His quest began early. When he was 5, the Alabama child-welfare workers decided that his mother’s boyfriend — a drug dealer named Rock who had a red carpet leading to his trailer and plaster lions standing guard at the door — wasn’t providing a suitable environment for John and his sisters and little brother. Before they knew it, they were living with their father, an Army officer stationed in Fayetteville, North Carolina. But two years later, when he was posted to Iraq, the social workers shipped the kids back to Alabama, where they stayed until their mother hanged herself from a tree in the yard. John was 14. In the tumultuous years that followed, he lost his faith, wrote mournful poems, took an interest in news reports about a lively new protest movement called Occupy Wall Street, and ran away from the home of the latest relative who’d taken him in — just for a night, but that was enough. As soon as he graduated from high school, he quit his job at McDonald’s, bought some camping gear, and set out in search of a better world.

When a young American lights out for the territories in the second decade of the 21st century, where does he go? For John Jacobi, the answer was Chapel Hill, North Carolina — Occupy had gotten him interested in anarchists, and he’d heard they were active there. He was camping out with the chickens in the backyard of their communal headquarters a few months later when a crusty old anarchist with dreadlocks and a piercing gaze handed him a dog-eared book called Industrial Society and Its Future. The author was FC, whoever that was. Jacobi glanced at the first line: “The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race.”

This guy sure gets to the point, he thought. He skimmed down the paragraph. Industrial society has caused “widespread psychological suffering” and “severe damage to the natural world”? Made life more comfortable in rich countries but miserable in the Third World? That sounded right to him. He found a quiet nook and read on.

The book was written in 232 numbered sections, like an instruction manual for some immense tool. There were two main themes. First, we’ve become so dependent on technology that the real decisions about our lives are made by unseen forces like corporations and market flows. Our lives are “modified to fit the needs of this system,” and the diseases of modern life are the result: “Boredom, demoralization, low self-esteem, inferiority feelings, defeatism, depression, anxiety, guilt, frustration, hostility, spouse or child abuse, insatiable hedonism, abnormal sexual behavior, sleep disorders, eating disorders, etc.” Jacobi had experienced most of those himself.

Get unlimited access to Intelligencer and everything else New YorkLEARN MORE »

The second point was that technology’s dark momentum can’t be stopped. With each improvement, the graceful schooner that sails our shorelines becomes the hulking megatanker that takes our jobs. The car’s a blast bouncing along at the reckless speed of 20 mph, but pretty soon we’re buying insurance, producing our license and registration if we fail to obey posted signs, and cursing when one of those charming behavior-modification devices in orange envelopes shows up on our windshields. We doze off while exploring a fun new thing called social media and wake up to big data, fake news, and Total Information Awareness.

All true, Jacobi thought. Who the hell wrote this thing?

The clue arrived in section No. 96: “In order to get our message before the public with some chance of making a lasting impression, we’ve had to kill people,” the mystery author wrote.

Kaczynski at the time of his arrest, in 1996. Photo: Donaldson Collection/Getty Images

“Kill people” — Jacobi realized that he was reading the words of the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, the hermit who sent mail bombs to scientists, executives, and computer experts beginning in 1978. FC stood for Freedom Club, the pseudonym Kaczynski used to take credit for his attacks. He said he’d stop if the newspapers published his manifesto, and they did, which is how he got caught, in 1995 — his brother recognized his prose style and reported him to the FBI. Jacobi flipped back to the first page, section No. 4: “We therefore advocate a revolution against the industrial system.”

The first time he read that passage, Jacobi had just nodded along. Talking about revolution was the anarchist version of praising the baby Jesus, invoked so frequently it faded into background noise. But Kaczynski meant it. He was a genius who went to Harvard at 16 and made breakthroughs in something called “boundary functions” in his 20s. He joined the mathematics department at UC Berkeley when he was 25, the youngest hire in the university’s then-99-year history. And he did try to escape the world he could no longer bear by moving to Montana. He lived in peace without electricity or running water until the day when, maddened by the invasion of cars and chain saws and people, he hiked to his favorite wild place for some relief and found a road cut through it. “You just can’t imagine how upset I was,” he told an interviewer in 1999. “From that point on, I decided that, rather than trying to acquire further wilderness skills, I would work on getting back at the system. Revenge.” In the next 17 years, he killed three people and wounded 23 more.

Jacobi didn’t know most of those details yet, but he couldn’t find any holes in Kaczynski’s logic. He said straight-out that ordinary human beings would never charge the barricades, shouting, “Destroy our way of life! Plunge us into a desperate struggle for survival!” They’d probably just stagger along, patching holes and destroying the planet, which meant “a small core of deeply committed people” would have to do the job themselves (section No. 189). Kaczynski even offered tactical advice in an essay titled “Hit Where It Hurts,” published a few years after he began his life sentence in a federal “supermax” prison in Colorado: Forget the small targets and attack critical infrastructure like electric grids and communication networks. Take down a few of those at the right time and the ripples would spread rapidly, crashing the global economic system and giving the planet a breather: No more CO2 pumped into the atmosphere, no more iPhones tracking our every move, no more robots taking our jobs.

Kaczynski was just as unsentimental about the downsides. Sure, decades or centuries after the collapse, we might crawl out of the rubble and get back to a simpler, freer way of life, without money or debt, in harmony with nature instead of trying to fight it. But before that happened, there was likely to be “great suffering” — violent clashes over resources, mass starvation, the rise of warlords. The way Kaczynski saw it, though, the longer we go like we’re going, the worse things will get. At the time his manifesto was published, many people reading it probably hadn’t heard of global warming and most certainly weren’t worried about it. Reading it in 2014 was a very different experience.

The shock that went through Jacobi in that moment — you could call it his “Kaczynski Moment” — made the idea of destroying civilization real. And if Kaczynski was right, wouldn’t he have some responsibility to do something, to sabotage one of those electric grids?

His answer was yes, which was almost as alarming as discovering an unexpected kinship with a serial killer — even when you’re sure that morality is just a social construct that keeps us docile in our shearing pens, it turns out setting off a chain of events that could kill a lot of people can raise a few qualms.

“But by then,” Jacobi says, “I was already hooked.”

Jacobi in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Photo: Colby Katz

Quietly, often secretly, whether they gather it from the air of this anxious era or directly from the source like Jacobi did, more and more people have been having Kaczynski Moments. Books and webzines with names like Against Civilization, FeralCulture, Unsettling America, and the Ludd-Kaczynski Institute of Technology have been spreading versions of his message across social-media forums from Reddit to Facebook for at least a decade, some attracting more than 100,000 followers. They cluster around a youthful nickname, “anti-civ,” some drawing their ideas directly from Kaczynski, others from movements like deep ecology, anarchy, primitivism, and nihilism, mixing them into new strains. Although they all believe industrial civilization is in a death spiral, most aren’t trying to hurry it along. One exception is Deep Green Resistance, an activist network inspired by a 2011 book of the same name that includes contributions from one of Kaczynski’s frequent correspondents, Derrick Jensen. The group’s openly stated goal, like Kaczynski’s, is the destruction of civilization and a return to preagricultural ways of life.

So far, most of the violence has happened outside of the United States. Although the FBI declined to comment on the topic, the 2017 report on domestic terrorism by the Congressional Research Service cited just a handful of minor attacks on “symbols of Western civilization” in the past ten years, a period of relative calm most credit to Operation Backfire, the FBI crackdown on radical environmental efforts in the mid-aughts. But in Latin America and Europe, terrorist groups with florid names like Conspiracy of Cells of Fire and Wild Indomitables have been bombing government buildings and assassinating technologists for almost a decade. The most ominous example is Individualidades Tendiendo a lo Salvaje, or ITS (usually translated as Individuals Tending Toward the Wild), a loose association of terrorist groups started by Mexican Kaczynski devotees who decided that his plan to take down the system was outdated because the environment was being decimated so fast and government surveillance technology had gotten so robust. Instead, ITS would return to its guru’s old modus operandi: revenge. The group set off bombs at the National Ecology Institute in Mexico, a Federal Electricity Commission office, two banks, and a university. It now claims cells across Latin America, and in January 2017, the Chilean offshoot delivered a gift-wrapped bomb to Oscar Landerretche, the chairman of the world’s largest copper mine, who suffered minor injuries. The group explained its motives in a defiant media release: “The pretentious Landerretche deserved to die for his offenses against Earth.”

In the larger world, where no respectable person would praise Kaczynski without denouncing his crimes, little Kaczynski Moments have been popping up in the most unexpected places — the Fox News website, for example, which ran a piece by Keith Ablow called “Was the Unabomber Correct?” in 2013. After summarizing some of Kaczynski’s dark predictions about the steady erosion of individual autonomy in a world where the tools and systems that create prosperity are too complex for any normal person to understand, Ablow — Fox’s “expert on psychiatry” — came to the conclusion that Kaczynski was “precisely correct in many of his ideas” and even something of a prophet. “Watching the development of Facebook heighten the narcissism of tens of millions of people, turning them into mini reality-TV versions of themselves,” he wrote. “I would bet he knows, with even more certainty, that he was onto something.”

That same year, in the leading environmentalist journal Orion, a “recovering environmentalist” named Paul Kingsnorth — who’d stunned his fellow activists in 2008 by announcing that he’d lost hope — published an essay about the disturbing experience of reading Kaczynski’s manifesto for the first time. If he ended up agreeing with Kaczynski, “I’m worried that it may change my life,” he confessed. “Not just in the ways I’ve already changed it (getting rid of my telly, not owning a credit card, avoiding smartphones and e-readers and sat-navs, growing at least some of my own food, learning practical skills, fleeing the city, etc.) but properly, deeply.”

By 2017, Kaczynski was making inroads with the conservative intelligentsia — in the journal First Things, home base for neocons like Midge Decter and theologians like Michael Novak, deputy editor Elliot Milco described his reaction to the manifesto in an article called “Searching for Ted Kaczynski”: “What I found in the text, and in letters written by Kaczynski since his incarceration, was a man with a large number of astute (even prophetic) insights into American political life and culture. Much of his thinking would be at home in the pages of First Things.” A year later, Foreign Policy published “The Next Wave of Extremism Will Be Green,” an editorial written by Jamie Bartlett, a British journalist who tracks the anti-civ movement. He estimated that a “few thousand” Americans were already prepared to commit acts of destruction. Citing examples such as the Standing Rock pipeline protests in 2017, Bartlett wrote, “The necessary conditions for the radicalization of climate activism are all in place. Some groups are already showing signs of making the transition.”

The fear of technology seems to grow every day. Tech tycoons build bug-out estates in New Zealand, smartphone executives refuse to let their kids use smartphones, data miners find ways to hide their own data. We entertain ourselves with I Am Legend, The Road, V for Vendetta, and Avatar while our kids watch Wall-E or FernGully: The Last Rainforest. An eight-part docudrama called Manhunt: The Unabomber was a hit when it premiered on the Discovery Channel in 2017 and a “super hit” when Netflix rereleased it last summer, says Elliott Halpern, the producer Netflix commissioned to make another film focusing on Kaczynski’s “ideas and legacy.” “Obviously,” Halpern says, “he predicted a lot of stuff.”

And wouldn’t you know it, Kaczynski’s papers have become one of the most popular attractions at the University of Michigan’s Labadie Collection, an archive of original documents from movements of “social unrest.” Kaczynski’s archivist, Julie Herrada, couldn’t say much about the people who visit — the archive has a policy against characterizing its clientele — but she did offer a word in their defense. “Nobody seems crazy.”

Two years ago, I started trading letters with Kaczynski. His responses are relentlessly methodical and laced with footnotes, but he seems to have a droll side, too. “Thank you for your undated letter postmarked 6/11/18, but you wrote the address so sloppily that I’m surprised the letter reached me …” “Thank you for your letter of 8/6/18, which I received on 8/16/18. It looks like a more elaborate and better developed, but otherwise typical, example of the type of brown-nosing that journalists send to a ‘mark’ to get him to cooperate.” Questions that revealed unfamiliarity with his work were poorly received. “It seems that most big-time journalists are incapable of understanding what they read and incapable of transmitting facts accurately. They are frustrated fiction-writers, not fact-oriented people.” I tried to warm him up with samples of my brilliant prose. “Dear John, Johnny, Jack, Mr. Richardson, or whatever,” he began, before informing me that my writing reminded him of something the editor of another magazine told the social critic Paul Goodman, as recounted in Goodman’s book Growing Up Absurd: “ ‘If you mean to tell me,” an editor said to me, “that Esquire tries to have articles on serious issues and treats them in such a way that nothing can come of it, who can deny it?’ ” (Kaczynski’s characteristically scrupulous footnote adds a caveat, “Quoted from memory.”) His response to a question about his political preferences was extra dry: “It’s certainly an oversimplification to say that the struggle between left & right in America today is a struggle between the neurotics and the sociopaths (left = neurotics, right = sociopaths = criminal types),” he said, “but there is nevertheless a good deal of truth in that statement.”

But the jokes came to an abrupt stop when I asked for his take on America’s descent into immobilizing partisan warfare. “The political situation is complex and could be discussed endlessly, but for now I will only say this,” he answered. “The current political turmoil provides an environment in which a revolutionary movement should be able to gain a foothold.” He returned to the point later with more enthusiasm: “Present situation looks a lot like situation (19th century) leading up to Russian Revolution, or (pre-1911) to Chinese Revolution. You have all these different factions, mostly goofy and unrealistic, and in disagreement if not in conflict with one another, but all agreeing that the situation is intolerable and that change of the most radical kind is necessary and inevitable. To this mix add one leader of genius.”

Kaczynski was Karl Marx in modern flesh, yearning for his Lenin. In my next letter, I asked if any candidates had approached him. His answer was an impatient no — obviously any revolutionary stupid enough to write to him would be too stupid to lead a revolution. “Wait, I just thought of an exception: John Jacobi. But he’s a screwball — bad judgment — unreliable — a problem rather than a help.”

The Kaczynski moment dislocates. Suddenly, everyone seems to be living in a dream world. Why are they talking about binge TV and the latest political outrage when we’re turning the goddamn atmosphere into a vast tanker of Zyklon B? Was he right? Were we all gelded and put in harnesses without even knowing it? Is this just a simulation of life, not life itself?

People have moments like that under normal conditions, of course. Sigmund Freud wrote a famous essay about them way back in 1929, Civilization and Its Discontents. A few unsettled souls will always quit that bank job and sail to Tahiti, and the stoic middle will always suck it up. But Jacobi couldn’t accept those options. Staggered by the shock of his Kaczynski Moment but intent on rising to the challenge, he began corresponding with the great man himself, hitchhiked the 644 miles from Chapel Hill to Ann Arbor to read the Kaczynski archives, tracked down his followers all around the world, and collected an impressive (and potentially incriminating) cache of material on ITS along the way. He even published essays about them in an alarmingly terror-friendly print journal named Atassa. But his biggest influence was a mysterious Spanish radical theorist known only by the pseudonym he used to translate Kaczynski’s manifesto into Spanish, Último Reducto. Recommended by Kaczynski himself, who even supplied an email address, Reducto gave Jacobi a daunting reading list and some editorial advice on his early essays, which inspired another series of TV-movie twists in Jacobi’s turbulent life. Frustrated by the limits of his knowledge, he applied to the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, to study some more, received a full scholarship and a small stipend, and buckled down for two years of intense scholarship. Then he quit and hit the road again. “I think the homeless are a better model than ecologically minded university students,” he told me. “They’re already living outside of the structures of society.”

Four years into this bizarre pilgrimage, Jacobi is something of an underground figure himself — the ubiquitous, eccentric, freakishly intellectual kid who became the Zelig of ecoextremism. Right now, he’s about to skin his first rat. Barefoot and shirtless, with an old wool blanket draped over his shoulders, long sun-streaked hair and gleaming blue eyes, he hurries down a rocky mountain trail toward a stone-age village of wattle-and-daub huts, softening his voice to finish his thought. “Ted was a good start. But Ted is not the endgame.”

He stops there. The village ahead is the home of a “primitive skills” school called Wild Roots. Blissfully untainted by modern conveniences like indoor toilets and hot showers, it’s also free of charge. It has just three rules, and only one that will get us kicked out. “I don’t want to be associated with that name,” Wild Roots’ de facto leader told us when I mentioned Kaczynski. “I don’t want my name associated with that name,” he added. “I really don’t want to be associated with that name.”

Jacobi arrives at the open-air workshop, covered by a tin roof, where the dirtiest Americans I’ve ever seen are learning how to weave cordage from bark, start friction fires, skin animals. The only surprise is the lives they led before: a computer analyst for a military-intelligence contractor, a Ph.D. candidate in engineering, a classical violinist, two schoolteachers, and a rotating cast of college students the older members call the “pre-postapocalypse generation.” Before he became the community blacksmith, the engineering student was testing batteries for ecofriendly cars. “It was a fucking hoax,” he says now. “It wasn’t going to make any difference.” At his coal-fired forge, pounding out simple tools with a hammer and anvil, he feels much more useful. “I can’t make my own axes yet, but I made most of the handles on those tools, I make all my own punches and chisels. I made an adze. I can make knives.”

Freshly killed this morning, five dead rats lie on a pine board. They’re for practice before trying to skin larger game. Jacobi bends down for a closer look, selects a rat, ties a string to its twiggy leg, and hangs it from a rafter. He picks up a razor. “You wanna leave the cartilage in the ear,” his teacher says. “Then cut just above the white line and you’ll get the eyes off.”

A few feet away, a young woman who fled an elite women’s college in Boston pounds a wooden staff into a bucket to pulverize hemlock bark to make tannin to tan the bear hide she has soaking in the stream — a mixture of mashed hemlock and brain tissue is best, she says, though eggs can substitute if you can’t get fresh brain.

Jacobi works the razor carefully. The eyes fall into the dirt.

“I’m surprised you haven’t skinned a rat before,” I say.

“Yeah, me too,” he replies.

He is, after all, the founder of The Wildernist and Hunter/Gatherer, two of the more radical web journals in the personal “rewilding” movement. The moderates at places like ReWild University talk of “rewilding your taste buds” and getting in “rockin’ fit shape.” “We don’t have to demonize our culture or attempt to hide from it,” ReWild University’s website enthuses. Jacobi has no interest in padding the walls of the cage — as he put it in an essay titled “Taking Rewilding Seriously,” “You can’t rewild an animal in a zoo.”