'Watchmen' Creator Alan Moore: Superhero Movies May Have Contributed To Trump's Rise

Jeremy Blum HuffPost•October 10, 2020

Alan Moore — the famed British co- creator of the graphic novels “Watchmen” and “V for Vendetta” and writer of dozens of DC and Marvel comics — offered a blistering critique of comics and argued that superhero movies may very well have contributed to the rise of Donald Trump and Brexit.

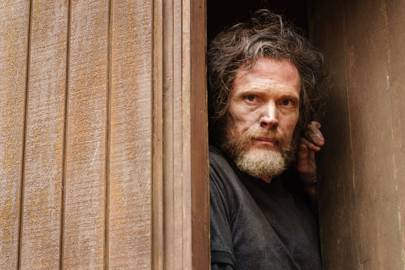

“I’m not so interested in comics anymore,” Moore said in a rare interview in Deadline on Friday. He is promoting his upcoming film, “The Show,” a nightmarish tale set in Northampton, England.

Moore retired from writing comics in 2018 after the release of the final issue of the “League of Extraordinary Gentlemen” series, which inspired the 2003 Sean Connery film of the same name.

“I had been doing comics for 40-something years when I finally retired,” Moore said. “When I entered the comics industry, the big attraction was that this was a medium that was vulgar. It had been created to entertain working-class people, particularly children. The way that the industry has changed, it’s ‘graphic novels’ now. It’s entirely priced for an audience of middle-class people. I have nothing against middle-class people, but it wasn’t meant to be a medium for middle-aged hobbyists. It was meant to be a medium for people who haven’t got much money.”

Moore added that mainstream audiences today tend to equate comics with superhero films, much to his displeasure. Moore slowly transitioned away from superhero stories over the course of his career, partly because of his negative experience working with DC, which he said “managed to successfully swindle” him through constricting contracts after the publication of “Watchmen” in the 1980s.

Since then, Moore criticized movies based on his stories. Following the negative reception of the “League of Extraordinary Gentlemen” movie, Moore asked that his name be removed from all film versions of his work. Neither the 2009 movie based on his seminal comic series “Watchmen” or HBO’s 2019 sequel TV series bear his name.

“I haven’t seen a superhero movie since the first Tim Burton ‘Batman’ film,” Moore told Deadline. “They have blighted cinema and also blighted culture to a degree. Several years ago I said I thought it was a really worrying sign, that hundreds of thousands of adults were queuing up to see characters that were created 50 years ago to entertain 12-year-old boys. That seemed to speak to some kind of longing to escape from the complexities of the modern world and go back to a nostalgic, remembered childhood. That seemed dangerous; it was infantilizing the population.”

Moore — who added that the best version of “Batman” in his opinion was the campy 1966 Adam West TV show, “which didn’t take it at all seriously” — speculated that an overabundance of superhero cinema may even have led to the current political state of the world.

“This may be entirely coincidence, but in 2016 when the American people elected a National Socialist satsuma and the U.K. voted to leave the European Union, six of the top 12 highest-grossing films were superhero movies,” Moore said. “Not to say that one causes the other, but I think they’re both symptoms of the same thing — a denial of reality and an urge for simplistic and sensational solutions.”

Jeremy Blum HuffPost•October 10, 2020

Alan Moore — the famed British

“I’m not so interested in comics anymore,” Moore said in a rare interview in Deadline on Friday. He is promoting his upcoming film, “The Show,” a nightmarish tale set in Northampton, England.

Moore retired from writing comics in 2018 after the release of the final issue of the “League of Extraordinary Gentlemen” series, which inspired the 2003 Sean Connery film of the same name.

“I had been doing comics for 40-something years when I finally retired,” Moore said. “When I entered the comics industry, the big attraction was that this was a medium that was vulgar. It had been created to entertain working-class people, particularly children. The way that the industry has changed, it’s ‘graphic novels’ now. It’s entirely priced for an audience of middle-class people. I have nothing against middle-class people, but it wasn’t meant to be a medium for middle-aged hobbyists. It was meant to be a medium for people who haven’t got much money.”

Moore added that mainstream audiences today tend to equate comics with superhero films, much to his displeasure. Moore slowly transitioned away from superhero stories over the course of his career, partly because of his negative experience working with DC, which he said “managed to successfully swindle” him through constricting contracts after the publication of “Watchmen” in the 1980s.

Since then, Moore criticized movies based on his stories. Following the negative reception of the “League of Extraordinary Gentlemen” movie, Moore asked that his name be removed from all film versions of his work. Neither the 2009 movie based on his seminal comic series “Watchmen” or HBO’s 2019 sequel TV series bear his name.

“I haven’t seen a superhero movie since the first Tim Burton ‘Batman’ film,” Moore told Deadline. “They have blighted cinema and also blighted culture to a degree. Several years ago I said I thought it was a really worrying sign, that hundreds of thousands of adults were queuing up to see characters that were created 50 years ago to entertain 12-year-old boys. That seemed to speak to some kind of longing to escape from the complexities of the modern world and go back to a nostalgic, remembered childhood. That seemed dangerous; it was infantilizing the population.”

Moore — who added that the best version of “Batman” in his opinion was the campy 1966 Adam West TV show, “which didn’t take it at all seriously” — speculated that an overabundance of superhero cinema may even have led to the current political state of the world.

“This may be entirely coincidence, but in 2016 when the American people elected a National Socialist satsuma and the U.K. voted to leave the European Union, six of the top 12 highest-grossing films were superhero movies,” Moore said. “Not to say that one causes the other, but I think they’re both symptoms of the same thing — a denial of reality and an urge for simplistic and sensational solutions.”

‘Watchmen’ Creator Talks New Project ‘The Show’, How Superhero Movies Have “Blighted Culture” & Why He Wants Nothing To Do With Comics

By Tom Grater

International Film Reporter@tomsmovies

By Tom Grater

International Film Reporter@tomsmovies

October 9, 2020 8:13am

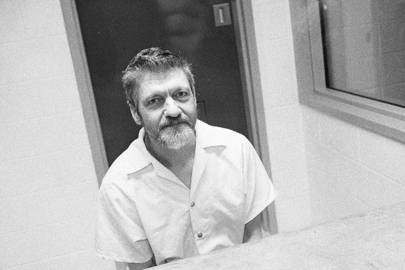

Alan Moore AP

EXCLUSIVE: As the creator of Watchmen, V For Vendetta and many more celebrated comic series, Alan Moore is one of the industry’s biggest names, but his frosty relationship with the film adaptations of his works has been well documented. After some very public dissatisfaction with previous endeavours (see The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen), he now refuses to let his name be linked with any such projects, even declining to profit from the big-screen incarnations, a decision that he estimates has cost him millions.

MOORE: Sometimes it was, all art-forms are potentially. But they can be used for something other than escapism. Think of all the films that have really challenged assumptions, films that have been difficult to take on board, disturbing in their messages. The same goes for literature. But these superhero films are too often escapism.

With regards to The Show, I think it’s an interesting case in point. I am known, perhaps a bit unfairly, for creating dystopias – I think I’ve done one or two but the rest are just my reflections on the world as I see it. With The Show, it could very well be argued that it is actually set in a dystopia, in that Northampton is the first British town in something like 35 years to collapse into an economic blackhole. We went into special measures in the early months of 2018. We can only afford skeleton services. They’re now talking about breaking it up into two different voting areas, which I imagine will make it Conservative until the end of time. There are a lot of failed social visions, mismanagement, but the imaginary life of the town… it has odd little pockets of surrealism and bizarreness that are still there, same as they’ve ever been, that are coming to the fore as Northampton’s waking reality has been so disjointed. The Show is an observed fantasy on a number of levels, but an awful lot of it is true. The town really is that odd-looking.

DEADLINE: In retirement, are you still creating, do you still write?

MOORE: I’ve only retired from comics. I’m finishing off a book of magic now. It’s been stalled for a while but I’m also working on an opera about John Dee with [musician] Howard Gray. I’ve got some short stories coming out. And I’ve also been thinking a lot about what we want to do after The Show feature film. We hope that it’s enjoyable as a thing in itself, but to some degree it could be seen as an incredibly elaborate pilot episode, we think there’s quite an interesting story that we could develop out of it as a TV series, which would imaginatively be called The Show.

EXCLUSIVE: As the creator of Watchmen, V For Vendetta and many more celebrated comic series, Alan Moore is one of the industry’s biggest names, but his frosty relationship with the film adaptations of his works has been well documented. After some very public dissatisfaction with previous endeavours (see The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen), he now refuses to let his name be linked with any such projects, even declining to profit from the big-screen incarnations, a decision that he estimates has cost him millions.

Deadline

Now, Moore is attempting to break into the film business on his own terms with original project The Show. Starring Tom Burke and directed by Mitch Jenkins, the fantastical adventure, set in Moore’s hometown of Northampton, follows a man’s search for a stolen artefact, a journey that leads him into a surreal world of crime and mystery.

Moore, who tends to duck the limelight, gave a rare interview to Deadline this week to discuss The Show, which has been something of a passion project for the writer. Him and his producers have kept it independent every step of the way, insisting on retaining creative control and rights to their own IP. After making several shorts film and now this feature, Moore has plans for a TV series based on the same characters and has already worked out 4-5 seasons worth of material, he tells us.

I also took the chance to ask him about retiring from comics in 2018, which his followers will be disappointed to hear he seems firmly set on, as well as his take on the current world of blockbuster superhero films, which he has been an inadvertent factor in. Safe to say, he is not a fan. He’s also not a fan of the current UK or U.S. political regimes, particularly Donald Trump, or “National Socialist satsuma”, as Moore refers to him.

The Show would have premiered at SXSW earlier this year, but following the Austin event’s cancellation it is headed to Spanish genre festival Sitges where it will debut online October 8 before a physical screening on October 12. Protagonist Pictures is handling world sales.

DEADLINE: Hi Alan, what’s your lockdown experience in Northampton been like?

ALAN MOORE: Me and my wife Melinda are still effectively living in late February – it’s about the same temperature. We are ignoring all advice from the government because we don’t think they have our best interests at heart, we’re just doing what we think is the most sensible thing, we’re maintaining distancing, having our stuff delivered. We haven’t seen or touched anybody in the last six months.

On the other hand, we’re finding that we’re closer to people even though we haven’t seen them in the flesh for ages. We’re spending a lot more time calling up and reading stories to our grandchildren, which is a lot of fun. Things that we didn’t find the time for back when the world was trundling ahead. Yes we miss everybody, but at the same time I can see different sorts of bonds forming. We will keep informed by listening to proper doctor and scientists.

DEADLINE: You retired from comics after finishing The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen in 2018, any thoughts on getting back in the saddle?

Now, Moore is attempting to break into the film business on his own terms with original project The Show. Starring Tom Burke and directed by Mitch Jenkins, the fantastical adventure, set in Moore’s hometown of Northampton, follows a man’s search for a stolen artefact, a journey that leads him into a surreal world of crime and mystery.

Moore, who tends to duck the limelight, gave a rare interview to Deadline this week to discuss The Show, which has been something of a passion project for the writer. Him and his producers have kept it independent every step of the way, insisting on retaining creative control and rights to their own IP. After making several shorts film and now this feature, Moore has plans for a TV series based on the same characters and has already worked out 4-5 seasons worth of material, he tells us.

I also took the chance to ask him about retiring from comics in 2018, which his followers will be disappointed to hear he seems firmly set on, as well as his take on the current world of blockbuster superhero films, which he has been an inadvertent factor in. Safe to say, he is not a fan. He’s also not a fan of the current UK or U.S. political regimes, particularly Donald Trump, or “National Socialist satsuma”, as Moore refers to him.

The Show would have premiered at SXSW earlier this year, but following the Austin event’s cancellation it is headed to Spanish genre festival Sitges where it will debut online October 8 before a physical screening on October 12. Protagonist Pictures is handling world sales.

DEADLINE: Hi Alan, what’s your lockdown experience in Northampton been like?

ALAN MOORE: Me and my wife Melinda are still effectively living in late February – it’s about the same temperature. We are ignoring all advice from the government because we don’t think they have our best interests at heart, we’re just doing what we think is the most sensible thing, we’re maintaining distancing, having our stuff delivered. We haven’t seen or touched anybody in the last six months.

On the other hand, we’re finding that we’re closer to people even though we haven’t seen them in the flesh for ages. We’re spending a lot more time calling up and reading stories to our grandchildren, which is a lot of fun. Things that we didn’t find the time for back when the world was trundling ahead. Yes we miss everybody, but at the same time I can see different sorts of bonds forming. We will keep informed by listening to proper doctor and scientists.

DEADLINE: You retired from comics after finishing The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen in 2018, any thoughts on getting back in the saddle?

The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen Titan Books

MOORE: I’m not so interested in comics anymore, I don’t want anything to do with them.

I had been doing comics for 40-something years when I finally retired. When I entered the comics industry, the big attraction was that this was a medium that was vulgar, it had been created to entertain working class people, particularly children. The way that the industry has changed, it’s ‘graphic novels’ now, it’s entirely priced for an audience of middle class people. I have nothing against middle class people but it wasn’t meant to be a medium for middle aged hobbyists. It was meant to be a medium for people who haven’t got much money.

Most people equate comics with superhero movies now. That adds another layer of difficulty for me. I haven’t seen a superhero movie since the first Tim Burton Batman film. They have blighted cinema, and also blighted culture to a degree. Several years ago I said I thought it was a really worrying sign, that hundreds of thousands of adults were queuing up to see characters that were created 50 years ago to entertain 12-year-old boys. That seemed to speak to some kind of longing to escape from the complexities of the modern world, and go back to a nostalgic, remembered childhood. That seemed dangerous, it was infantilizing the population.

This may be entirely coincidence but in 2016 when the American people elected a National Socialist satsuma and the UK voted to leave the European Union, six of the top 12 highest grossing films were superhero movies. Not to say that one causes the other but I think they’re both symptoms of the same thing – a denial of reality and an urge for simplistic and sensational solutions.

DEADLINE: You said you feel responsible for how comics have changed, why?

MOORE: It was largely my work that attracted an adult audience, it was the way that was commercialized by the comics industry, there were tons of headlines saying that comics had ‘grown up’. But other than a couple of particular individual comics they really hadn’t.

This thing happened with graphic novels in the 1980s. People wanted to carry on reading comics as they always had, and they could now do it in public and still feel sophisticated because they weren’t reading a children’s comic, it wasn’t seen as subnormal. You didn’t get the huge advances in adult comic books that I was thinking we might have. As witnessed by the endless superhero films…

DEADLINE: What’s your take on the comics industry now?

MOORE: I doubt the major companies will be coming out of lockdown in any shape at all. The mainstream comics industry is about 80 years old and it has lots of pre-existing health conditions. It wasn’t looking that great before COVID happened.

Most of our entertainment industries have been a bit top heavy for a while. The huge corporations, business interests, have so much money they can produce these gigantic blockbusters of one sort or another that will dominate their markets. I can see that changing, and perhaps for the better. It’s too early to make optimistic predictions but you might hope that the bigger interests will find it more difficult to manoeuvre in this new landscape, whereas the smaller independent concerns might find that they are a bit more adapted. These times might be an opportunity for genuinely radical and new voices to come to the fore in the absence of yesteryear.

DEADLINE: The economic realties, and lack of support for the arts, could hamper that.

MOORE: That is undeniable. I am talking in the long-term. There is going to be an awful lot of economic pain for everybody before this is over. I’m not even sure it ever will technically be over, until we’ve reached a better stage of equilibrium, whatever that turns out to be. When that was attained I hope we might see a very different landscape culturally.

DEADLINE: Do you watch no superhero movies at all? What about something a bit offbeat, like Joker? You wrote a key Batman comic book…

MOORE: Oh christ no I don’t watch any of them. All of these characters have been stolen from their original creators, all of them. They have a long line of ghosts standing behind them. In the case of Marvel films, Jack Kirby [the Marvel artist and writer]. I have no interest in superheroes, they were a thing that was invented in the late 1930s for children, and they are perfectly good as children’s entertainment. But if you try to make them for the adult world then I think it becomes kind of grotesque.

MOORE: I’m not so interested in comics anymore, I don’t want anything to do with them.

I had been doing comics for 40-something years when I finally retired. When I entered the comics industry, the big attraction was that this was a medium that was vulgar, it had been created to entertain working class people, particularly children. The way that the industry has changed, it’s ‘graphic novels’ now, it’s entirely priced for an audience of middle class people. I have nothing against middle class people but it wasn’t meant to be a medium for middle aged hobbyists. It was meant to be a medium for people who haven’t got much money.

Most people equate comics with superhero movies now. That adds another layer of difficulty for me. I haven’t seen a superhero movie since the first Tim Burton Batman film. They have blighted cinema, and also blighted culture to a degree. Several years ago I said I thought it was a really worrying sign, that hundreds of thousands of adults were queuing up to see characters that were created 50 years ago to entertain 12-year-old boys. That seemed to speak to some kind of longing to escape from the complexities of the modern world, and go back to a nostalgic, remembered childhood. That seemed dangerous, it was infantilizing the population.

This may be entirely coincidence but in 2016 when the American people elected a National Socialist satsuma and the UK voted to leave the European Union, six of the top 12 highest grossing films were superhero movies. Not to say that one causes the other but I think they’re both symptoms of the same thing – a denial of reality and an urge for simplistic and sensational solutions.

DEADLINE: You said you feel responsible for how comics have changed, why?

MOORE: It was largely my work that attracted an adult audience, it was the way that was commercialized by the comics industry, there were tons of headlines saying that comics had ‘grown up’. But other than a couple of particular individual comics they really hadn’t.

This thing happened with graphic novels in the 1980s. People wanted to carry on reading comics as they always had, and they could now do it in public and still feel sophisticated because they weren’t reading a children’s comic, it wasn’t seen as subnormal. You didn’t get the huge advances in adult comic books that I was thinking we might have. As witnessed by the endless superhero films…

DEADLINE: What’s your take on the comics industry now?

MOORE: I doubt the major companies will be coming out of lockdown in any shape at all. The mainstream comics industry is about 80 years old and it has lots of pre-existing health conditions. It wasn’t looking that great before COVID happened.

Most of our entertainment industries have been a bit top heavy for a while. The huge corporations, business interests, have so much money they can produce these gigantic blockbusters of one sort or another that will dominate their markets. I can see that changing, and perhaps for the better. It’s too early to make optimistic predictions but you might hope that the bigger interests will find it more difficult to manoeuvre in this new landscape, whereas the smaller independent concerns might find that they are a bit more adapted. These times might be an opportunity for genuinely radical and new voices to come to the fore in the absence of yesteryear.

DEADLINE: The economic realties, and lack of support for the arts, could hamper that.

MOORE: That is undeniable. I am talking in the long-term. There is going to be an awful lot of economic pain for everybody before this is over. I’m not even sure it ever will technically be over, until we’ve reached a better stage of equilibrium, whatever that turns out to be. When that was attained I hope we might see a very different landscape culturally.

DEADLINE: Do you watch no superhero movies at all? What about something a bit offbeat, like Joker? You wrote a key Batman comic book…

MOORE: Oh christ no I don’t watch any of them. All of these characters have been stolen from their original creators, all of them. They have a long line of ghosts standing behind them. In the case of Marvel films, Jack Kirby [the Marvel artist and writer]. I have no interest in superheroes, they were a thing that was invented in the late 1930s for children, and they are perfectly good as children’s entertainment. But if you try to make them for the adult world then I think it becomes kind of grotesque.

Batman: The Killing Joke DC Comics

I’ve been told the Joker film wouldn’t exist without my Joker story (1988’s Batman: The Killing Joke), but three months after I’d written that I was disowning it, it was far too violent – it was Batman for christ’s sake, it’s a guy dressed as a bat. Increasingly I think the best version of Batman was Adam West, which didn’t take it at all seriously. We have a kind of superhero character in The Show but if we get the chance to develop them more then people will be able to see all of the characters have quite unusual aspects to them.

I’ve been told the Joker film wouldn’t exist without my Joker story (1988’s Batman: The Killing Joke), but three months after I’d written that I was disowning it, it was far too violent – it was Batman for christ’s sake, it’s a guy dressed as a bat. Increasingly I think the best version of Batman was Adam West, which didn’t take it at all seriously. We have a kind of superhero character in The Show but if we get the chance to develop them more then people will be able to see all of the characters have quite unusual aspects to them.

MOORE: Sometimes it was, all art-forms are potentially. But they can be used for something other than escapism. Think of all the films that have really challenged assumptions, films that have been difficult to take on board, disturbing in their messages. The same goes for literature. But these superhero films are too often escapism.

With regards to The Show, I think it’s an interesting case in point. I am known, perhaps a bit unfairly, for creating dystopias – I think I’ve done one or two but the rest are just my reflections on the world as I see it. With The Show, it could very well be argued that it is actually set in a dystopia, in that Northampton is the first British town in something like 35 years to collapse into an economic blackhole. We went into special measures in the early months of 2018. We can only afford skeleton services. They’re now talking about breaking it up into two different voting areas, which I imagine will make it Conservative until the end of time. There are a lot of failed social visions, mismanagement, but the imaginary life of the town… it has odd little pockets of surrealism and bizarreness that are still there, same as they’ve ever been, that are coming to the fore as Northampton’s waking reality has been so disjointed. The Show is an observed fantasy on a number of levels, but an awful lot of it is true. The town really is that odd-looking.

DEADLINE: In retirement, are you still creating, do you still write?

MOORE: I’ve only retired from comics. I’m finishing off a book of magic now. It’s been stalled for a while but I’m also working on an opera about John Dee with [musician] Howard Gray. I’ve got some short stories coming out. And I’ve also been thinking a lot about what we want to do after The Show feature film. We hope that it’s enjoyable as a thing in itself, but to some degree it could be seen as an incredibly elaborate pilot episode, we think there’s quite an interesting story that we could develop out of it as a TV series, which would imaginatively be called The Show.

‘The Show’ Protagonist Pictures

I’ve worked out about four-five seasons of potential episodes. We’re showing that around to people to see how it goes, if there should be any interest I am prepared to launch myself into that. We’re not asking for a huge amount of money we’re just asking for control over the work and ownership over the work, if that is something people are prepared to give us we have no problem with people making money out of it. What we have got a problem with is us losing our rights to the ownership of the material, and having the work interfered with in any way.

DEADLINE: It sounds like the kind of thing Netflix might be interested in, but retaining your IP might be an issue…

MOORE: We shall see. There are options. All we need is to own our IP. But that’s why it has taken us so long to get to the feature film stage, and to get the five short films made previously. I really don’t have an interest in writing for movies or television per se, it has to be on my terms, which I think are fair ones. I’ve got no problem with other people making money from those works.

DEADLINE: Fair to say you’ve earned that right.

MOORE: I think so.

DEADLINE: Why make the shorts first?

MOORE: When we were trying to get this made some people wanted us to make a short film that would later be made into a feature film. As soon as it was announced that I was doing any sort of film there was suddenly a lot of interest in it. People said it could be a short that turned into a feature and a TV series, like This Is England. I realised without changing it I could open up the story, it could become a much bigger narrative.

DEADLINE: And you used the shorts to attract the feature finance?

MOORE: The BFI nobly gave us just over £1m if we could get someone to match that. It went on for a few years with various partners getting involved but not being able to work out the financial details. I was coming to the end of my rope and then we heard the financing was in place and we had something like £3m and could go ahead and make the film in November 2018.

We started on schedule, but I noticed there seemed to be a lot of the investors gathering around Mitch [Jenkins, director] in the early days of the film. When we finally got it finished we had a modest wrap party at a local restaurant, I thought it was a good-looking film for £3m, and then Mitch said, ‘we didn’t do that for £3m’… apparently just before the film was due to start soothing, some of the investors pulled out, they said it would take another year or two to raise the money again but someone said if I heard this had happened they would probably never see me again. They gave Mitch a chance to make it for £1m but were breathing down his neck to make sure he met all the deadlines. I believe we got it shot for £900,000, I don’t think it looks like a £900,000 movie…

DEADLINE: It certainly doesn’t. Did you have to make compromises?

MOORE: There was one scene that was removed because there wasn’t time for it. There might have been small changes but not really significantly. The main good fortune was that we had Northampton at our disposal, perhaps the only good thing about having the town on its knees is that the council are absolutely desperate for anything that will draw any kind of financial attention to this collapsed hellhole. They gave us the freedom of the town.

DEADLINE: What are your hopes for the film?

MOORE: I hope people will enjoy it and will be interested enough to see how the story will evolve in a TV series. I hope that all the people who worked on the film, including the brilliant actors, get the recognition. But all of that is in the lap of the gods.

DEADLINE: I’m a huge fan of Tom Burke…

MOORE: Absolutely, he’s terrific, he brought such a lot to the character and he’s a terrific guy as well. I particularly enjoyed my scene with Tom.

DEADLINE: How long did it take you to get into that makeup? [See below]

MOORE: Oh, hours. Our makeup designer was an absolute genius, she did it as quickly as anybody could

I’ve worked out about four-five seasons of potential episodes. We’re showing that around to people to see how it goes, if there should be any interest I am prepared to launch myself into that. We’re not asking for a huge amount of money we’re just asking for control over the work and ownership over the work, if that is something people are prepared to give us we have no problem with people making money out of it. What we have got a problem with is us losing our rights to the ownership of the material, and having the work interfered with in any way.

DEADLINE: It sounds like the kind of thing Netflix might be interested in, but retaining your IP might be an issue…

MOORE: We shall see. There are options. All we need is to own our IP. But that’s why it has taken us so long to get to the feature film stage, and to get the five short films made previously. I really don’t have an interest in writing for movies or television per se, it has to be on my terms, which I think are fair ones. I’ve got no problem with other people making money from those works.

DEADLINE: Fair to say you’ve earned that right.

MOORE: I think so.

DEADLINE: Why make the shorts first?

MOORE: When we were trying to get this made some people wanted us to make a short film that would later be made into a feature film. As soon as it was announced that I was doing any sort of film there was suddenly a lot of interest in it. People said it could be a short that turned into a feature and a TV series, like This Is England. I realised without changing it I could open up the story, it could become a much bigger narrative.

DEADLINE: And you used the shorts to attract the feature finance?

MOORE: The BFI nobly gave us just over £1m if we could get someone to match that. It went on for a few years with various partners getting involved but not being able to work out the financial details. I was coming to the end of my rope and then we heard the financing was in place and we had something like £3m and could go ahead and make the film in November 2018.

We started on schedule, but I noticed there seemed to be a lot of the investors gathering around Mitch [Jenkins, director] in the early days of the film. When we finally got it finished we had a modest wrap party at a local restaurant, I thought it was a good-looking film for £3m, and then Mitch said, ‘we didn’t do that for £3m’… apparently just before the film was due to start soothing, some of the investors pulled out, they said it would take another year or two to raise the money again but someone said if I heard this had happened they would probably never see me again. They gave Mitch a chance to make it for £1m but were breathing down his neck to make sure he met all the deadlines. I believe we got it shot for £900,000, I don’t think it looks like a £900,000 movie…

DEADLINE: It certainly doesn’t. Did you have to make compromises?

MOORE: There was one scene that was removed because there wasn’t time for it. There might have been small changes but not really significantly. The main good fortune was that we had Northampton at our disposal, perhaps the only good thing about having the town on its knees is that the council are absolutely desperate for anything that will draw any kind of financial attention to this collapsed hellhole. They gave us the freedom of the town.

DEADLINE: What are your hopes for the film?

MOORE: I hope people will enjoy it and will be interested enough to see how the story will evolve in a TV series. I hope that all the people who worked on the film, including the brilliant actors, get the recognition. But all of that is in the lap of the gods.

DEADLINE: I’m a huge fan of Tom Burke…

MOORE: Absolutely, he’s terrific, he brought such a lot to the character and he’s a terrific guy as well. I particularly enjoyed my scene with Tom.

DEADLINE: How long did it take you to get into that makeup? [See below]

MOORE: Oh, hours. Our makeup designer was an absolute genius, she did it as quickly as anybody could

.

Protagonist Pictures

READ MORE ABOUT:

ALAN MOORE

ALAN MOORE