Pulitzer Prize-shortlisted author Mara Hvistendahl gives her story of the theft of industrial and scientific secrets a vital human dimension

Her book follows the case of one Chinese scientist through its many twists and turns and looks at a troubling history of suspicion

Kit Gillet 8 Feb, 2020

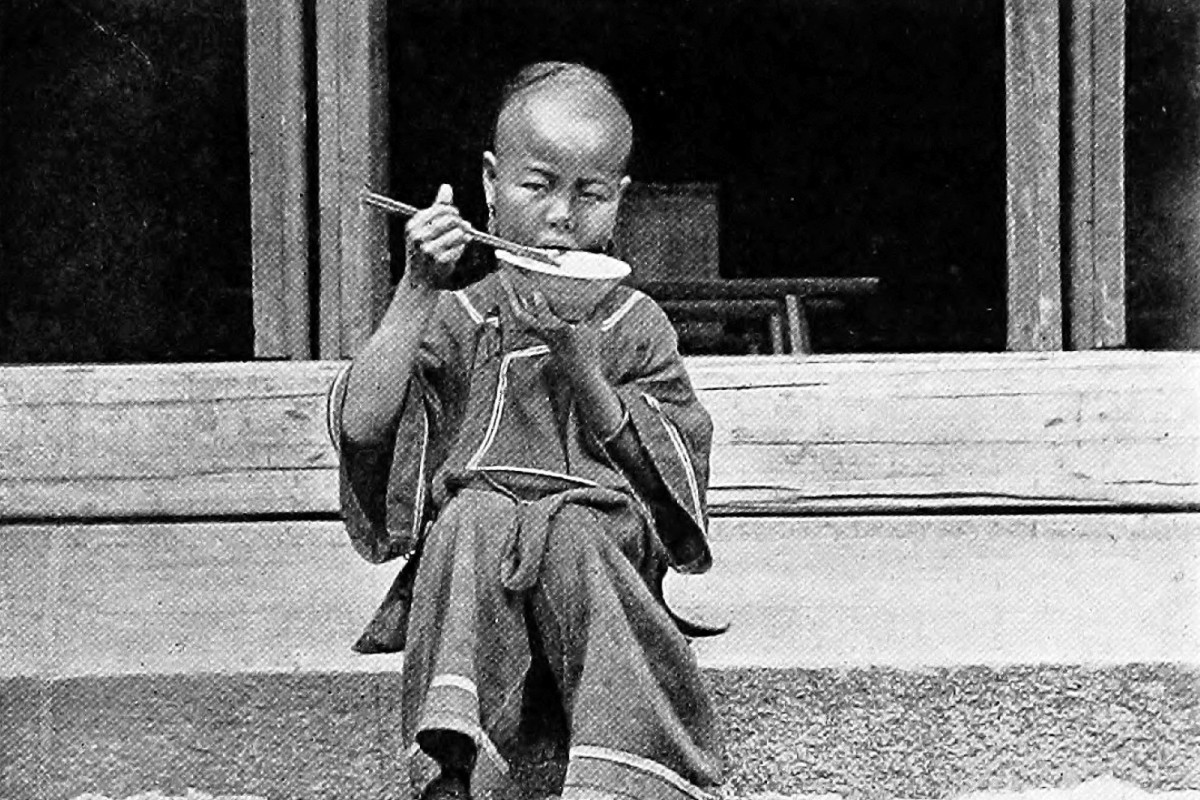

An American farmer tests seeds for Monsanto, an agricultural giant that guards its intellectual property with great secrecy, determination and, when necessary, aggressive lawsuits. Photo: Getty Images

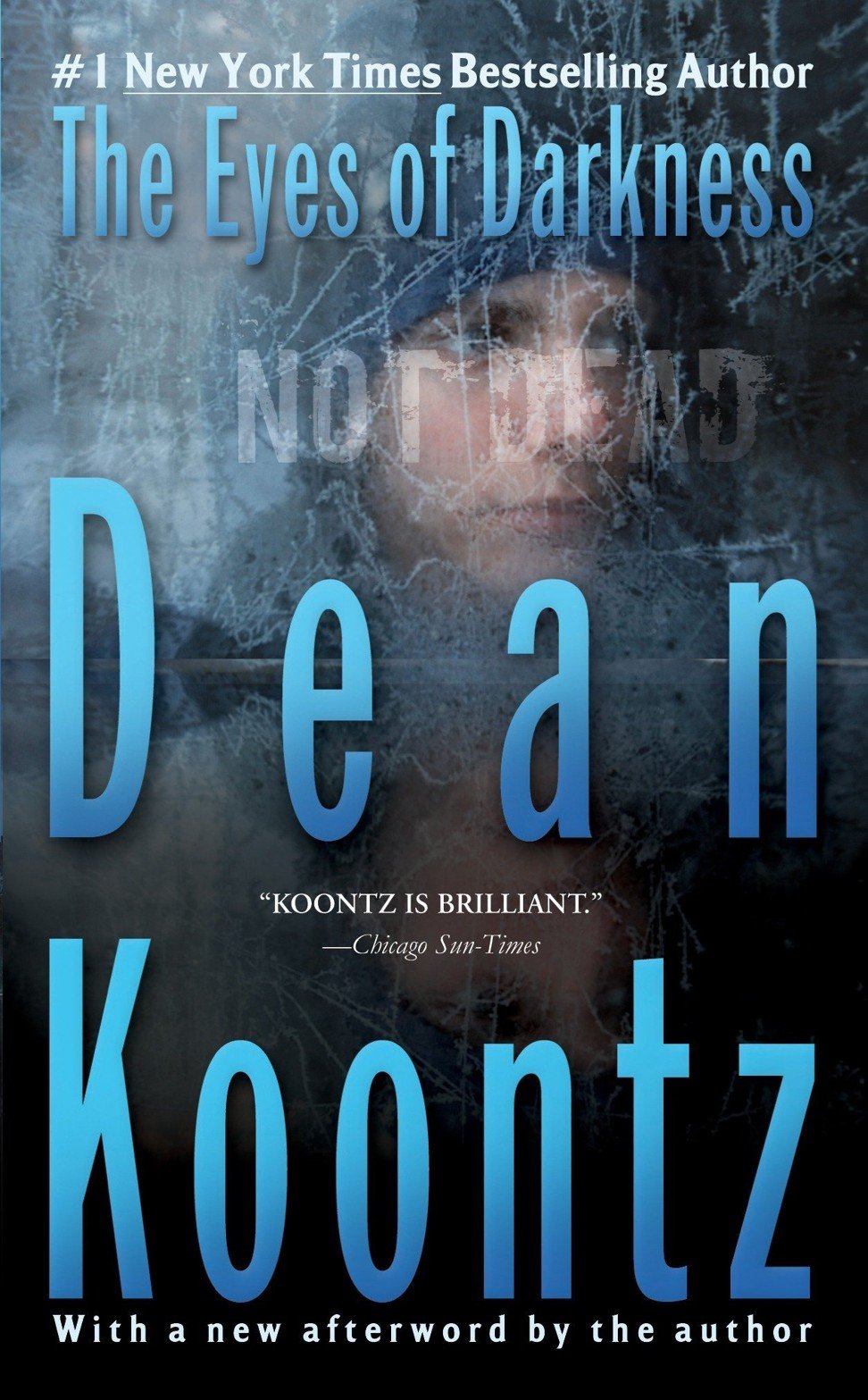

The Scientist and the Spy: A True Story of China, the FBI, and Industrial Espionage

by Mara Hvistendahl

Riverhead Books

4/5 stars

A smartly dressed Chinese man was spotted in a field in rural Iowa, in the United States, in autumn 2011. This was enough to raise suspicion in a community that was 97 per cent white and the local police went to check it out.

Thus began perhaps one of the stranger cases of industrial espionage in recent years, one that highlights the threat of industrial theft and the overblown atmosphere of fear and mistrust that exists between the United States and China over intellectual property and trade.

The field in question was planted with genetically modified seed lines developed by agricultural giant Monsanto, a company that guards its intellectual property – like hybrid seeds and fertiliser – with great secrecy, determination and, when necessary, aggressive lawsuits.

Racial profiling? In the US, Chinese heritage can make you into a spy

31 Jan 2020

The Chinese man and his two companions – who circled back around in their car to pick him up – were questioned by police but let go with a warning. However, their details were taken down and later one of the names, Robert Mo, began cropping up in other incidents in rural communities across the Midwest.

This is the starting point of The Scientist and the Spy: A True Story of China, the FBI, and Industrial Espionage, by journalist and Pulitzer Prize-shortlisted author Mara Hvistendahl. The book follows this one case through its many twists and turns, but also looks at the atmosphere of fear – sometimes justified, sometimes not – in the West over Chinese theft of industrial and scientific secrets.

The book delves into the history of the FBI monitoring ethnically Chinese scientists in the US going back to the 1960s. It also documents the impact on the lives of some of those accidentally caught up in this geopolitical tug of war.

Industrial espionage is as old as industry itself. However, with the rise of China as a superpower, increasing attention is again being paid to the issue on a nation-to-nation level. In many ways it echoes tensions between the US and the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

US President Donald Trump has accused China of orchestrating “the greatest theft in the history of the world”, while the value of intellectual property stolen each year by China is often put at US$300 billion, though, as the book makes clear, this is largely based on rough estimates and anecdotal evidence. Intellectual property is one of the core issues at the heart of the ongoing trade war between China and the US.

As Hvistendahl points out, China’s central government has placed a high priority on strategic industrial breakthroughs “no matter how they are achieved”. The US Chamber of Commerce labelled one Chinese state document on indigenous innovation “a blueprint for technology theft on a scale the world has never seen before”.

Agriculture is one of many areas in which China is seeking rapid advancement, given both the lucrative nature of the sector and the importance of food security. The need for China to increase yields to feed its massive population means that the pressure on those tasked with developing cutting-edge hybrid seeds for crops such as corn is considerable, as is the temptation to cut corners.

In the early 2000s there were, by one count, 8,700 Chinese seed companies and “none of them had successfully managed to create seed lines that rivalled those of the international seed outfits”, Hvistendahl writes. As such, getting their hands on advanced genetically modified seeds to reverse engineer was a big advantage, albeit an illegal one. “Real research takes time. Theft is expedient – especially if there is little chance of getting caught,” she adds.

Enter Mo, one of the men questioned that autumn day in 2011 and the principal character in the story. Born in Sichuan province, he moved to the US in the late 1990s after training in thermodynamics, but later joined his brothers-in-law’s agricultural business after failing to secure well-paying research work. His role was initially to source animal feed in the US, but soon he was tasked with helping the company’s seed-breeding programme.

This mostly involved trying to get his hands on hybrid seeds produced by American companies, sometimes legally but often not. Mo and his colleagues would drive around rural areas collecting loose seeds from the ground soon after harvest time in fields they knew had been planted with genetically modified crops. At other times they would buy from seed suppliers, who were supposed to ensure that the seeds were used only for that year’s harvest. They would then be sent back to China for analysis.

How China’s blatant IP theft, long overlooked by US, sparked trade war

19 Nov 2018

The Scientist and the Spy makes it clear early on that Mo would be caught by the FBI, so we know how the story ends. However, the journey, filled with colourful characters and episodes that could be straight out of a spy novel, paints an illuminating and often disturbing picture of how the fight over industrial secrets plays out, a fight that increasingly involves both companies and governments.

In 1996, the US government signed into law the Economic Espionage Act, which made trade secret theft a federal crime. As such, attacks on American business are considered a national security threat and those caught can receive sentences of up to 10 years behind bars and a fine of US$250,000, even if there is no clear government connection with their actions. If a government link can be made, sentences can be up to 15 years and the fine twice as much.

Companies like Monsanto often hire former federal agents as part of their security operations.

The Scientist and the Spy follows Mo’s case all the way through to its conclusion, documenting the massive operation that would eventually involve years of work and dozens of agents across five states. Agents placed listening devices in rental cars, intercepted phone calls and flew surveillance planes overhead to monitor the movement of the suspects, among many other operations.

However, the book doesn’t just focus on this one case. It also looks into the troubling history of Chinese scientists, students and researchers suspected of trying to steal US trade secrets.

Some were indeed found guilty – including Kexue Huang, who was sentenced to seven years in prison in 2011 for stealing Dow pesticide secrets – but many simply came under the FBI’s watchful eye due to their ethnicity. In 2006, Wen Ho Lee, a Taiwanese-born scientist working in Los Alamos in New Mexico, was awarded a US$1.6 million settlement, partly paid by The New York Times, after he was falsely accused of stealing secrets connected to the US nuclear arsenal and had his name leaked to the press.

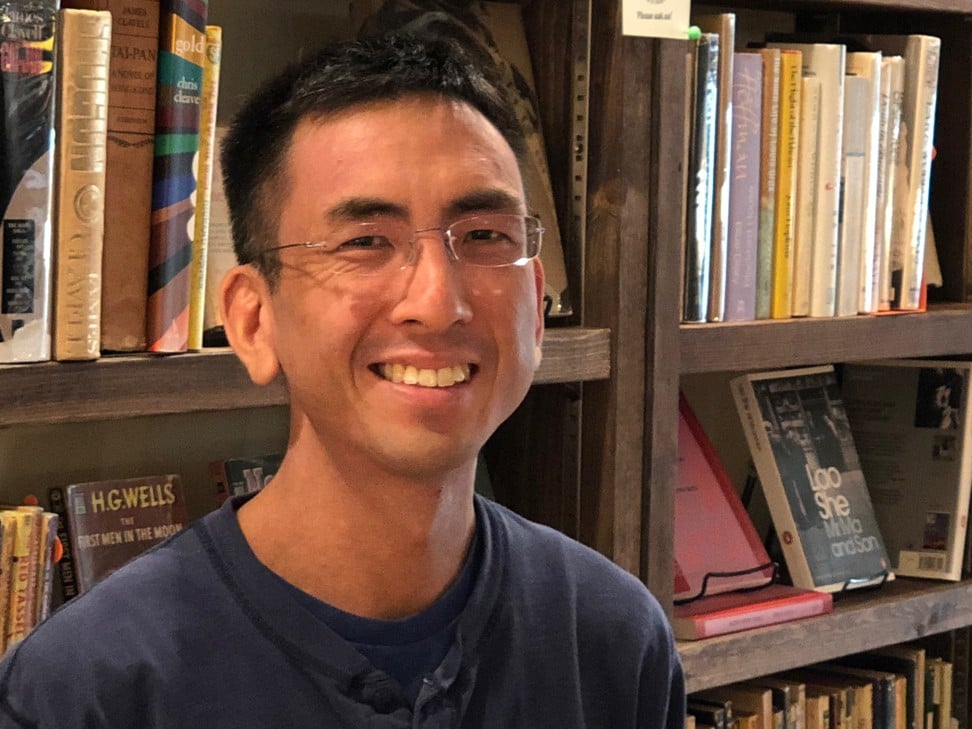

Author Mara Hvistendahl.

One scholar found that about a fifth of cases brought up under the Economic Espionage Act between 1996 and 2015 that involved Chinese names were never proven, roughly twice the rate of defendants from other ethnic groups. Hvistendahl contends that the level of suspicion has meant that countless ethnically Chinese students have opted to pursue educational or career opportunities elsewhere in the world, rather than in the US.

The Scientist and the Spy is painstakingly researched, and relies heavily on extensive interviews with many of the principal characters on both sides of the law. It also looks into the effective monopoly that a handful of agricultural companies have on worldwide seed development, and the damage this is having on farmland and crop diversity, not to mention ecosystems.

Hvistendahl, who spent eight years reporting from China for Science magazine and was a 2012 finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for non-fiction for her book Unnatural Selection, brings her considerable experience to the subject.

When we think of industrial espionage we often think of state actors and large-scale operations. However, as The Scientist and the Spy makes clear, in many cases it is individuals with their own personal dramas and motivations attempting to access secrets. The book puts a human face to the issue of industrial espionage, and ultimately Mo comes across as a highly sympathetic character.

At a time when tensions between the US and China are high, The Scientist and the Spy offers an intriguing glimpse into how industrial espionage plays out, involving low-level players seemingly far removed from the centres of power.