Chinese immigrants went to Australia looking for gold and found communities. Why does so little of their legacy remain?

Chinese history

Driven off Queensland’s goldfields, arrivals from China pioneered trade and agriculture in the north of the country, until discriminatory legislation and changing times forced them out

David Leffman 22 Feb, 2020

Gold fever hit Australia in 1851. Rushes swept the southern states of Victoria and New South Wales and fanned out across the country; whole towns emptied as people raced to the goldfields, hoping to “strike lucky” and make their fortunes. As news reached the outside world, Australia was overrun by migrant prospectors from Britain, Europe and, especially, China.

At the time, China was in chaos, ravaged by famine and civil war, and many Chinese came to the Antipodes from harsh rural backgrounds. With little to lose, they were willing to work hard for profits they could either send home to relatives or save for their own return. Mostly male, immigrants were divided by a range of dialects and clan loyalties, united by being strangers struggling to survive in a foreign and often unwelcoming land.

In far north Queensland, where Australia’s “finger” points towards New Guinea, so many Chinese came that, at one time, they outnumbered the European population by five to one. Many remained long after the gold had gone, pioneering local trade and agriculture and bringing substantial improvements to living conditions. And yet little trace of this Chinese heritage remains today.

In 1872, gold was discovered in far north Queensland’s remote Palmer River, a harsh country of open woodland, savannah and granite outcrops where temperatures top 40 degrees Celsius in summer. It was also home to Aboriginal peoples, who resented outsiders pouring into their territory, stripping the land of its resources. Violent exchanges between the two groups ensued, with fatalities on both sides.

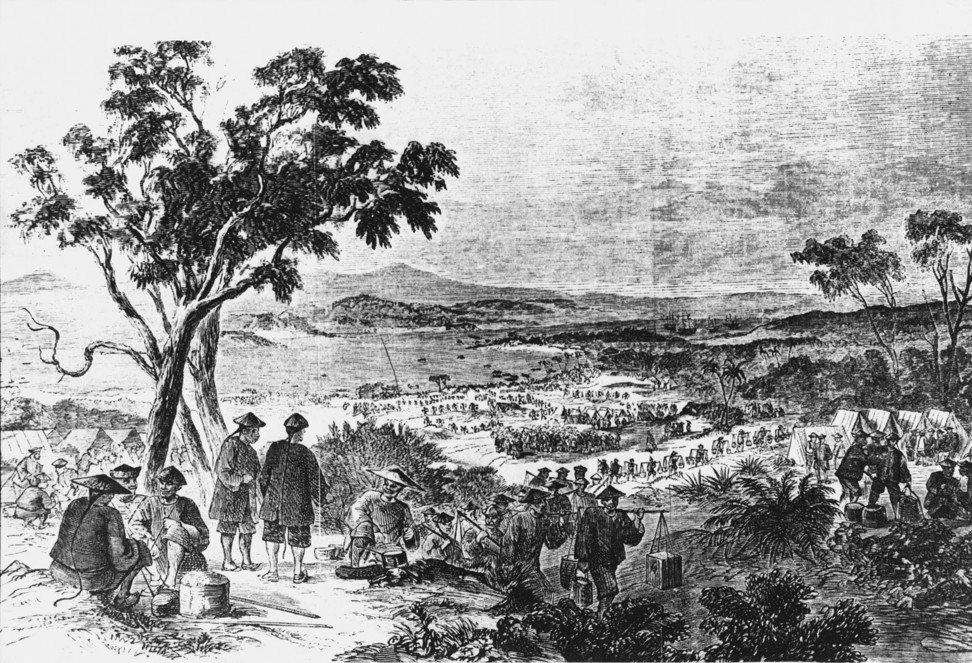

An illustration from 1870 shows Chinese workers on the

Queensland goldfields. Photo: Getty Images

Still the prospectors came in their thousands. Mining camps sprang up at Palmerville and Maytown, and the gateway coastal port of Cooktown was founded 140km to the northeast. The Palmer became Australia’s richest alluvial goldfield: the government warden recorded one prospector finding nuggets weighing 179oz (5kg; worth US$262,000 today) in just three hours, while another team panned 59lbs (26.8kg) of gold in three weeks (US$1.26 million).

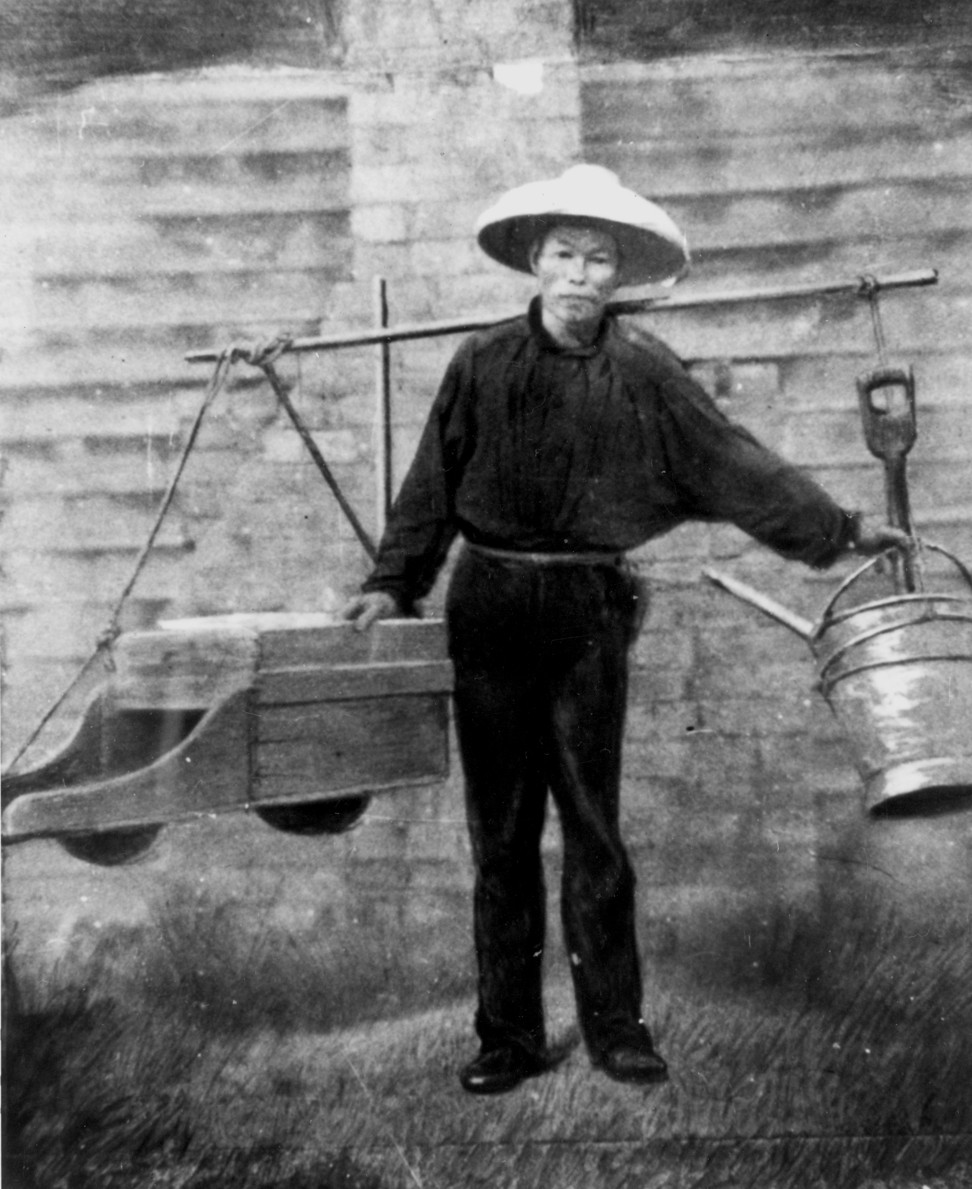

The first Chinese arrived on the Palmer goldfield in 1874 and were soon pouring in from the Pearl River region, on China’s southern coast, with steamships running directly from Hong Kong to Cooktown. The Australasian Sketcher magazine described newly arrived Chinese “thronging the roads to the Palmer diggings, where long strings of them can be seen stretched out in Indian file, each man laden with burdens swinging from the ends of his bamboo pole [...] Their loads consist of the most miscellaneous articles, tinware, chests of tea, bags of flour, tents and equipage, mining tools, clothes and all the other items of necessary equipment for mining life.”

Some died along the road from heatstroke, injury and Aboriginal attack. Controversial police inspector Frederic Urquhart reported that the Aboriginals were cannibals, and that they preferred Chinese to Europeans because they tasted better.

On the fields, the Chinese usually targeted workings abandoned as unprofitable by European miners, patiently extracting every last speck of gold. This ability to make money from “exhausted” claims and their sheer numbers – by 1877 there were 17,000 Chinese prospectors on the Palmer – fired racial friction, with white mobs raiding Chinese camps to cut off their long plaits of hair.

Still the prospectors came in their thousands. Mining camps sprang up at Palmerville and Maytown, and the gateway coastal port of Cooktown was founded 140km to the northeast. The Palmer became Australia’s richest alluvial goldfield: the government warden recorded one prospector finding nuggets weighing 179oz (5kg; worth US$262,000 today) in just three hours, while another team panned 59lbs (26.8kg) of gold in three weeks (US$1.26 million).

The first Chinese arrived on the Palmer goldfield in 1874 and were soon pouring in from the Pearl River region, on China’s southern coast, with steamships running directly from Hong Kong to Cooktown. The Australasian Sketcher magazine described newly arrived Chinese “thronging the roads to the Palmer diggings, where long strings of them can be seen stretched out in Indian file, each man laden with burdens swinging from the ends of his bamboo pole [...] Their loads consist of the most miscellaneous articles, tinware, chests of tea, bags of flour, tents and equipage, mining tools, clothes and all the other items of necessary equipment for mining life.”

Some died along the road from heatstroke, injury and Aboriginal attack. Controversial police inspector Frederic Urquhart reported that the Aboriginals were cannibals, and that they preferred Chinese to Europeans because they tasted better.

On the fields, the Chinese usually targeted workings abandoned as unprofitable by European miners, patiently extracting every last speck of gold. This ability to make money from “exhausted” claims and their sheer numbers – by 1877 there were 17,000 Chinese prospectors on the Palmer – fired racial friction, with white mobs raiding Chinese camps to cut off their long plaits of hair.

Read more

Oldest Chinatown in Australia faces suburban rival

Many Australians, like government warden William Hill, felt the Chinese were robbing the country of its rightful wealth: “Only for the influx of Chinamen the Palmer would have given profitable employment to thousands of Europeans for many years [...] The amount of gold obtained by them was enormous, and thousands of ounces of gold were taken back to China privately, as one of the Boss Chinamen told me.”

In 1877, the Queensland government enacted the Chinese Immigrants Regulation Act, which limited the numbers of Chinese arriving on any one ship, and taxed them £10 per head – equivalent to US$870 today. When that had little effect, the tax was raised to £30, and the Chinese were banned from working on newly discovered goldfields.

A Chinese gold prospector in the 1860s.

Photo: State Library of Queensland

Declining returns combined with hostile conditions and taxation eventually drove the Chinese off the Palmer. Some found jobs as cooks or timber workers, others set up in business at the newly established regional settlements of Cairns, Atherton and Innisfail. At the time, the government was leasing agricultural land to white developers, but in order to purchase the land freehold, “improvements” – clearing and planting – had to be made.

Many Europeans leased acreages at the low rate of £1 per acre a year to Chinese tenant farmers (who, unless naturalised, were not allowed to own land themselves). The soils proved fertile and, as many Chinese had previous farming experience, within a decade the area had become a major exporter of crops, shipping produce as far away as Melbourne.

Far north Queensland’s major city,

Declining returns combined with hostile conditions and taxation eventually drove the Chinese off the Palmer. Some found jobs as cooks or timber workers, others set up in business at the newly established regional settlements of Cairns, Atherton and Innisfail. At the time, the government was leasing agricultural land to white developers, but in order to purchase the land freehold, “improvements” – clearing and planting – had to be made.

Many Europeans leased acreages at the low rate of £1 per acre a year to Chinese tenant farmers (who, unless naturalised, were not allowed to own land themselves). The soils proved fertile and, as many Chinese had previous farming experience, within a decade the area had become a major exporter of crops, shipping produce as far away as Melbourne.

Far north Queensland’s major city,

Cairns, was founded in 1876 as a port for the newly discovered Hodgkinson goldfield, 140km inland. The first two Chinese attempting to land were literally thrown back into the water by European miners, who wanted to keep the Hodgkinson white. But Chinese migrants to Cairns were not there to risk their necks prospecting; instead they established market gardens and general stores to supply the growing township with goods, fresh tropical fruit and vegetables.

One of these early pioneers was Andrew Leon (1841-1920). Already 10 years in Australia and fluent in English, Leon became a major figure in Cairns’ development. “Around 1878 he selected 1,250 acres for the Hap Wah plantation, planting sugar and cotton, and in 1882 the plantation’s Pioneer mill produced the area’s first sugar exports,” says Julia Volkmar, of the Hap Wah and Andrew Leon Historical Project.

Kwong Sue Duk with three of his wives and fourteen of

his children in Cairns, in 1904. Photo: State Library of Queensland

After the sugar industry collapsed, Leon moved into property investment, including several businesses on Sachs Street (now Grafton), between Spence and Shields streets. This Chinatown strip eventually hosted restaurants, stores, hostels, banks, cottage industries, gaming halls, and several Japanese-run brothels. One of the district’s two temples, Lit Sung Goong, played a central role in the Chinese community and survived until 1966.

According to Sandi Robb, of the Cairns and District Chinese Association, by 1900 there were 1,600 Chinese in the Cairns area (compared with 4,000 Europeans), all but 28 of whom were male. Not surprisingly, a number married European women while others found brides in China and brought them out. Kwong Sue Duk – a naturalised Australian who settled in Cairns for a few years and ran a store and Chinese pharmacy – was famed for having four wives and 24 children (he has more than 800 descendants, including Australian celebrity chef Kylie Kwong).

The Chinese contribution to Cairns’ economy was apparent and, unlike on the goldfields, they were generally treated with respect. In 1888, the Anti-Chinese League was refused permission to hold a rally there, while a visiting cleric enthused about Chinese farmers supporting the Cairns region: “I don’t know how the people would get on without them.” The Chinese community raised money for local causes, and its Lunar New Year festivities, with fireworks, parades and lion dances, were the talk of the town. Complaints against Chinese tended to revolve around opium, prostitution and gambling, and their frequent use of the courts to try to ruin business rivals.

Up on the tablelands behind Cairns, the township of Atherton coalesced during the 1880s around a timber workers’ camp. There were already about 100 Chinese living there, many of them former gold miners, who now turned their hands to farming and successfully introduced maize. This put them in competition with Atherton’s European settlers, who wanted to use the same land to graze dairy cattle. The Chinese further ruffled feathers by storing surplus grain in good years and then selling it at high prices in times of shortage.

A statue of a Chinese gold prospector outside the Atherton

After the sugar industry collapsed, Leon moved into property investment, including several businesses on Sachs Street (now Grafton), between Spence and Shields streets. This Chinatown strip eventually hosted restaurants, stores, hostels, banks, cottage industries, gaming halls, and several Japanese-run brothels. One of the district’s two temples, Lit Sung Goong, played a central role in the Chinese community and survived until 1966.

According to Sandi Robb, of the Cairns and District Chinese Association, by 1900 there were 1,600 Chinese in the Cairns area (compared with 4,000 Europeans), all but 28 of whom were male. Not surprisingly, a number married European women while others found brides in China and brought them out. Kwong Sue Duk – a naturalised Australian who settled in Cairns for a few years and ran a store and Chinese pharmacy – was famed for having four wives and 24 children (he has more than 800 descendants, including Australian celebrity chef Kylie Kwong).

The Chinese contribution to Cairns’ economy was apparent and, unlike on the goldfields, they were generally treated with respect. In 1888, the Anti-Chinese League was refused permission to hold a rally there, while a visiting cleric enthused about Chinese farmers supporting the Cairns region: “I don’t know how the people would get on without them.” The Chinese community raised money for local causes, and its Lunar New Year festivities, with fireworks, parades and lion dances, were the talk of the town. Complaints against Chinese tended to revolve around opium, prostitution and gambling, and their frequent use of the courts to try to ruin business rivals.

Up on the tablelands behind Cairns, the township of Atherton coalesced during the 1880s around a timber workers’ camp. There were already about 100 Chinese living there, many of them former gold miners, who now turned their hands to farming and successfully introduced maize. This put them in competition with Atherton’s European settlers, who wanted to use the same land to graze dairy cattle. The Chinese further ruffled feathers by storing surplus grain in good years and then selling it at high prices in times of shortage.

A statue of a Chinese gold prospector outside the Atherton

Chinatown Hou Wang temple, in Queensland. Photo: David Leffman

Atherton’s Chinatown eventually became home to more than 1,000 people, its broad main street comprising 20 or so buildings – there were restaurants, stores, gaming halls, market gardens and the timber Hou Wang temple. This was a fairly modest three-room affair, decked in corrugated iron and dedicated to Yang Liangjie, bodyguard to the last emperor of the Song dynasty (960-1279); fittings included a bronze bell cast specially in China, and four auspicious paintings under the eaves. Atherton’s markets were brisk enough to draw business away from Cairns. The North Coast Advertiser reported, “The produce trade in Atherton is all in the hands of the Chinamen. They also have the best kept horses there, and are great horse dealers.”

Atherton’s Chinatown eventually became home to more than 1,000 people, its broad main street comprising 20 or so buildings – there were restaurants, stores, gaming halls, market gardens and the timber Hou Wang temple. This was a fairly modest three-room affair, decked in corrugated iron and dedicated to Yang Liangjie, bodyguard to the last emperor of the Song dynasty (960-1279); fittings included a bronze bell cast specially in China, and four auspicious paintings under the eaves. Atherton’s markets were brisk enough to draw business away from Cairns. The North Coast Advertiser reported, “The produce trade in Atherton is all in the hands of the Chinamen. They also have the best kept horses there, and are great horse dealers.”

Not that everything went their way. When prayers to Yang Liangjie failed to end a drought in the 1890s, irate farmers dragged his image out of the temple and kicked it into the river. (Three days later, Atherton was hit by a cyclone.) Another incident saw international affairs played out locally. After the abdication of China’s last emperor, in 1912, pro-imperial and pro-republic factions from across north Queensland descended on Atherton; the imperials – mostly wealthy merchants, gambling-den owners and shopkeepers – had kept their traditional plaited queues while the Republican labourers and farm workers had cut their hair short in support of the new regime. The two sides hurled “stones, bottles and other handy missiles” at each other, resulting in a dozen injuries and four arrests.

About 90km south of Cairns, near the mouth of the twisting Johnstone River, Innisfail (then called Geraldton) sprang up in the late 1870s as a supply town for local sugar cane plantations. One of its earliest Chinese residents was Tom See Poy (Taam Sze Pui; 1856-1926), whose autobiography sketches how he came to settle here. After the family farm in China was destroyed by flooding, he heard “a rumour that gold had been discovered [on the Palmer], the source of which was inexhaustible and free to all”, and caught a steamer from Hong Kong to Cooktown.

“He spent five years on the goldfields, barely covering expenses and suffering illness, injury and Aboriginal attack,” says his descendant, Bill Sue Yek. “Leaving to work on a sugar plantation at Innisfail, in 1882, he used his savings to found what became See Poy & Sons department store. With suppliers all over Australia, See Poy’s could sell you anything from an umbrella to a car.” The business survived until 1981.

The interior of Atherton’s Hou Wang temple. Photo: David Leffman

Innisfail is also known for its bananas, which grow prolifically in the region’s rich soils. According to local businessman and former mayor Herb Layt, Chinese firms such as Hop Kee and Man Cheong Long once dominated the banana trade, digging long canals between the fields and river so crops could be easily shipped out. A substantial Chinatown spread west from Innisfail’s riverfront, featuring the usual run of retail businesses, services and nightclubs, and even a furniture factory.

A visiting journalist described how the Chinese were everywhere. “He is the cook, the merchant, and the gardener, and indeed, it is the export of bananas by the Chinese that has kept Geraldton going during seasons when sugar cultivation has not been as promising as usual. Sugar is largely grown by the Chinamen at Geraldton, too.” As at Cairns, the community put on lively parades for Lunar New Year, and even for a visit by the Queensland premier in 1903.

By 1900 then, the Chinese were firmly established in far north Queensland, and their communities were thriving. So why did they decline?

In short, says Bill Sue Yek at Innisfail, it was due to a mixture of discriminatory legislation and changing times. North Queensland was losing its rough, pioneering edge and the towns had begun to attract white working-class settlers, who competed with the Chinese as labourers. Fears of unemployment led to Australia’s 1901 Immigration Restriction Act, the infamous “White Australia policy”, which greatly restricted non-British immigration.

Chinese workers transport bananas along a waterway,

in Innisfail. Photo: State Library of Queensland

At the same time, disease, poor transport infrastructure and overseas competition were undermining the banana industry. As profits fell, the Chinese were hit further by the Leases to Aliens Act and Banana Industry Preservation Act, again designed to exclude non-Europeans. In 1913, restrictions were also placed on the employment of Chinese in sugar production; and from 1917, to reward servicemen returning from the first world war, the Australian government handed out land packages as “soldier settlements”, including acreages leased by Chinese at Atherton.

Deprived of their livelihoods, the Chinese began leaving the far north. Some of the older generation retired back to China, but many Australian-born Chinese dispersed to wherever there was work, leaving the Chinatowns to fade away. Over the following decades local agriculture passed into the hands of a new wave of migrants fleeing poverty in their home countries, the Italians and Maltese, who were themselves superseded in the 1990s by Hmong refugees from Thailand and Laos.

Today, signs of Chinese presence are comparatively thin on the ground. Cairns’ once-thriving Chinatown is commemorated by a bus-shelter-style memorial on Grafton Street, and a plaque to Hap Wah inside Stocklands shopping centre, on the site of its former plantation. An active community of descendants of early Chinese families remains, however, along with an annual Lunar New Year street festival, and a planned cultural centre that will showcase a significant collection of artefacts from Lit Sung Goong temple.

Atherton’s Chinatown was abandoned by 1950 and the buildings scavenged, although the Hou Wang Temple remained more or less functional until 1975. The site was bought by the Fong On family and donated to the National Trust, which has restored the temple and set up a museum.

A Chinatown memorial in Cairns. Photo: David Leffman

Down at Innisfail, a memorial plaque inside Coles supermarket marks the now-demolished See Poy & Sons store and, on Owen Street, another Lit Sing Gung temple is a focus for the dwindling Chinese community. Painted vivid yellow and red, an angular concrete 1940s building replaced the original 19th century construction, destroyed by a cyclone. Lit Sing Gung once provided charitable accommodation for the poor and elderly, especially the first generation of Chinese settlers who decided not to return to China. Inside are reminders of busier times: gilded deity sculptures and altars, another bell, and a dedication board dated 1897 proclaiming, “A Heroic Breeze Bringing Righteousness”.

Temple committee treasurer Neville Lee, who traces his family back through the Australian goldfields to a 13th century Chinese magistrate, is vague about what happened to Innisfail’s community, describing its current numbers as “very few”.

Now retired, Layt has long promoted the development of Innisfail’s former Chinatown as a historic precinct. Yet the regional Cassowary Coast council’s 53-page “Innisfail Masterplan”, drawn up in 2018, does not mention the Chinese or Lit Sing Gung. This might be about to change. The council has plans to discuss the wider promotion of Chinese heritage with other regional tourism bodies, and hopes to work with the temple committee to develop a themed “Chinatown” district.

“We recognise that the Lit Sing Gung temple plays an important role in the fabric of the town,” says councillor Byron Jones. “The masterplan specifically focuses on public space improvements designed to bring more tourists through the centre of town and down to the riverbank, hopefully increasing patronage and awareness of the temple.”

At the same time, disease, poor transport infrastructure and overseas competition were undermining the banana industry. As profits fell, the Chinese were hit further by the Leases to Aliens Act and Banana Industry Preservation Act, again designed to exclude non-Europeans. In 1913, restrictions were also placed on the employment of Chinese in sugar production; and from 1917, to reward servicemen returning from the first world war, the Australian government handed out land packages as “soldier settlements”, including acreages leased by Chinese at Atherton.

Deprived of their livelihoods, the Chinese began leaving the far north. Some of the older generation retired back to China, but many Australian-born Chinese dispersed to wherever there was work, leaving the Chinatowns to fade away. Over the following decades local agriculture passed into the hands of a new wave of migrants fleeing poverty in their home countries, the Italians and Maltese, who were themselves superseded in the 1990s by Hmong refugees from Thailand and Laos.

Today, signs of Chinese presence are comparatively thin on the ground. Cairns’ once-thriving Chinatown is commemorated by a bus-shelter-style memorial on Grafton Street, and a plaque to Hap Wah inside Stocklands shopping centre, on the site of its former plantation. An active community of descendants of early Chinese families remains, however, along with an annual Lunar New Year street festival, and a planned cultural centre that will showcase a significant collection of artefacts from Lit Sung Goong temple.

Atherton’s Chinatown was abandoned by 1950 and the buildings scavenged, although the Hou Wang Temple remained more or less functional until 1975. The site was bought by the Fong On family and donated to the National Trust, which has restored the temple and set up a museum.

A Chinatown memorial in Cairns. Photo: David Leffman

Down at Innisfail, a memorial plaque inside Coles supermarket marks the now-demolished See Poy & Sons store and, on Owen Street, another Lit Sing Gung temple is a focus for the dwindling Chinese community. Painted vivid yellow and red, an angular concrete 1940s building replaced the original 19th century construction, destroyed by a cyclone. Lit Sing Gung once provided charitable accommodation for the poor and elderly, especially the first generation of Chinese settlers who decided not to return to China. Inside are reminders of busier times: gilded deity sculptures and altars, another bell, and a dedication board dated 1897 proclaiming, “A Heroic Breeze Bringing Righteousness”.

Temple committee treasurer Neville Lee, who traces his family back through the Australian goldfields to a 13th century Chinese magistrate, is vague about what happened to Innisfail’s community, describing its current numbers as “very few”.

Now retired, Layt has long promoted the development of Innisfail’s former Chinatown as a historic precinct. Yet the regional Cassowary Coast council’s 53-page “Innisfail Masterplan”, drawn up in 2018, does not mention the Chinese or Lit Sing Gung. This might be about to change. The council has plans to discuss the wider promotion of Chinese heritage with other regional tourism bodies, and hopes to work with the temple committee to develop a themed “Chinatown” district.

“We recognise that the Lit Sing Gung temple plays an important role in the fabric of the town,” says councillor Byron Jones. “The masterplan specifically focuses on public space improvements designed to bring more tourists through the centre of town and down to the riverbank, hopefully increasing patronage and awareness of the temple.”

---30---

No comments:

Post a Comment