Field Notes

New Pandemic, Old Story

One of the most remarkable aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic is the way it has made visible and concrete the links between the social, economic, and political systems we have created for ourselves and our health. These links have been manifested both in the effects of the pandemic itself as well as in the ways we have responded (or failed to respond) to it. A second no less remarkable aspect is the sheer magnitude and unprecedented nature of the global response, a response that has perhaps made it possible to experience glimmers of ways in which we could live and be organized differently. Whether the experience will lead to real change, or whether after deaths begin to drop (and the disease settles into endemic transmission among the most vulnerable) we will all return to business as usual remains to be seen.

On a very practical level, one striking aspect of the pandemic response has been how unprepared we appear to have been, despite decades of pandemic preparedness exercises. A striking example has been that a country like the United States, one of the wealthiest countries in the world and the one that spends the largest percentage of GDP on health care, failed miserably to respond to basic needs generated by the growing spread of the virus. Nothing illustrates this more clearly than the lack of access to the tests needed to identify cases and the scarcity of protective equipment needed to protect health care workers from becoming infected themselves. Given the critical importance of case identification and contact tracing as the core public health approach to controlling epidemics in early stages, it is likely that the scarcity of testing was a major determinant of the inability to stop the spread earlier resulting in extensive community transmission and the consequent need for draconian stay-at-home measures. The inability to ensure even the most basic protective gear for health care workers (so-called PPE or personal protective equipment) has placed many at risk. The ongoing saga regarding the availability and distribution of ventilators, which even had US states bidding against each other1 is yet another example. It could be argued that the surge in cases was faster than anticipated, yet even well into the pandemic it has been extremely challenging to provide these basic resources when and where they are needed. Where is “the invisible hand of the market” when we really need it?

Of course, the lack of testing and PPE are manifestations of a much broader problem: the lack of a coordinated and cohesive public health response for the country as a whole. As a result, jurisdictions all over the US have responded as best they can, often piecemeal and with minimum (if any) coordination across adjacent geographic areas. To make things worse, the limited access to testing has meant not only that case identification for purposes of isolation and contact becomes impossible but also that basic statistics regarding the epidemiology of the disease are just not available. We have limited data on the rate at which new cases are occurring or on the proportion of the population that has already been infected. Some suggest that in some settings cases may actually be as much as 10 times higher2 than those reported. Lack of testing may also be skewing key measures like the case fatality rate (the proportion of cases that die) as well as information on the proportion of all infections that are asymptomatic, and on how soon after acquiring the infection people can transmit the disease. Data like these are critical to modelling efforts that attempt to predict the number of cases, the number of hospitalized cases, and the number of deaths that we can expect within specific time periods. Lack of information on these very basic aspects of the epidemiology of the virus are behind the highly variable estimates of the impact of the pandemic generated by various modelling groups. Only recently has the Centers for Disease Control (the premier public health agency of the United States and many would argue across the world) announced the launching of a series of population studies aimed at obtaining vital information needed to guide our response. Although it has consistently issued clear guidance via its website, the agency has been amazingly absent in guiding and coordinating national policy which has been left to politicians with variable scientific input. In this vacuum various individuals, ad-hoc groups of scientists, and think tanks have put forward multiple point plans on how we should respond, often disseminated through journal articles, social media or the press. [(As I write this, several US governors have announced that they plan to form coalitions to do the sensible thing and begin to coordinate responses across states.)]

On a more positive note, it has been striking to observe how the health threat created by the virus motivated a halt to business as usual in ways that no one would have imagined, with the explicit goal of protecting health. As it became apparent that case identification and contact tracing was not going to work to stop transmission, place after place (sometimes whole countries, sometimes cities, sometimes states) adopted “stay at home orders” or even more restrictive curfews. In a matter of weeks schools, universities, and “non-essential” businesses grounded to a halt. Life was completely transformed. Children stayed home, universities shifted to remote teaching, large portions of the workforce were instructed to work from home, all social activities and non-essential travel ceased. All this, as has been repeatedly emphasized in the press, to “flatten the curve” in order to reduce the burden of cases on the health care system and hopefully to reduce the number of deaths. Regardless of whether one believes this was justified or not, at least on the face of it, it was an unprecedented prioritization of health over the economy. Only an infectious disease pandemic, something everyone could relate to because of the fear of “contagion” (and the images of refrigerated trailers holding bodies in New York City), could accomplish this. None of the other silent killers, the 4.2 million deaths3 attributable to air pollution every year, the 1.35 million road traffic fatalities4 worldwide each year, the over 250,000 annual deaths caused by firearms5 (nearly 700 a day), the increasing mortality and morbidity linked to climate change (heat, drought, and floods) have been enough to make us question, let alone interfere with, our economy. For comparison purposes, on the day I am writing this (April 12 2020) the World Health Organization reports a total of 112,652 deaths from COVID-19, although questions remain about the accuracy with which deaths are being attributed or not to the virus.

The fact that this social distancing was implemented so quickly and so pervasively is mind boggling. Surreal images of empty city streets abound. It is hard to deny that social distancing will have an impact on reducing disease transmission although the magnitude of this impact and how it compares to other options (such as intensive case identification and contact tracing coupled with some more limited social distancing measures) is hard to determine. Numerous modelling efforts have reported often widely disparate estimates of cases and deaths expected, and speculation about whether the social distancing measures have or have not worked abounds. We probably will not know for sure for a long time (if at all), when retrospective studies have been performed. But given the threat of large numbers of deaths and an overwhelmed health care system (which was certainly real in some regions like northern Italy and even New York City), there was consensus despite significant uncertainty (and even skepticism among some scientists) that no other option was possible. [(Certainly the need for drastic measures appears to be justified by recent data suggesting that deaths in New York City during the last month were more than twice6 what would have been expected.)]

Aside from its impact on the pandemic itself, the social distancing policies are a grand natural experiment that could affect health in many different ways. One of the obvious consequences is the impact of stay-at-home orders on the slowdown of economic activity with its consequences for unemployment. This was starkly illustrated by the 17 million unemployment claims filed in the US since the start of the pandemics until April 9. Many studies have documented short-term effects of unemployment on the deterioration of physical and mental health with implications not only for those who lose their jobs but for their families.

But the closing down of the economy has had other quite remarkable impacts. Air pollution levels have dropped precipitously. Traffic has been reduced to unprecedented levels. These reductions in themselves could have major health implications given the contributions of air pollution and traffic to deaths worldwide. This is consistent with research showing that despite the adverse effects of unemployment on individuals who become unemployed, economic recessions tend to be associated with improved population health in part likely because of reductions in traffic and air pollution related deaths. We have no data on other potential health impacts of stay-at-home orders and their economic and social effects. For example how have the shut downs affected physical activity and dietary patterns? Have they increased or decreased smoking and alcohol consumption? What have been the impacts on levels of stress and mental health? What about the long -term impact of an increase in gun purchases? Many cities including cities in Latin America have reported dramatic declines in homicide rates but there have also been reports of increases in deaths related to domestic violence. One could envision both positive and negative impacts, and the overall balance of these effects is at this point very hard to predict.

A major recent development (which will be old news and likely long gone from the media’s attention by the time you read this) has been the rediscovery by politicians and the media of something that public health has documented for centuries: the fact that diseases like COVID-19 (and virtually all others, both infectious and not) are strongly socially patterned. The unequal impacts of COVID-19 by social class and race has quickly begun to emerge as the pandemic progresses. Initial comments about “COVID-19 affecting everyone equally” while well-intentioned were, not unsurprisingly, grossly inaccurate. COVID-19 is striking the poor and the working class hardest. Despite limited data, we are beginning to see this pattern emerge in cities across the US. Recent reports have also highlighted higher rates of diseases in Black Americans.7 The poor and disadvantaged will get more disease, will experience more severe disease when they get infected, and those who get infected will likely die more.

The link between poverty or social class and infectious disease rates is not new,⁸ and is caused in part simply by increased exposure to the virus. Housing conditions that result in overcrowding tend to be more common in poorer neighborhoods resulting in greater disease transmission. Lower income workers are more likely to have jobs that increase their exposure to others who are infected and do not have the luxury of adopting the remote work arrangements that many of us benefit from. Underlying health conditions and psychosocial stress can also affect immune responses,⁹ making the poor more vulnerable to developing disease when exposed to infectious agents. In the case of COVID-19, the poor and working classes will not only get more disease, they will also get sicker when they get it and will likely die more from it. Decades of data demonstrate that chronic diseases like respiratory and heart disease and risk factors like smoking, which make persons more vulnerable to severe and deadly COVID-19 disease, have a clear gradient by social class. In the US access to healthcare and quality of care received also differ by income and race.10 If rationing needs to be implemented, the poor and communities of color who are more likely to have underlying health conditions making their prognosis worse,11 may not fare well.

The poor and working classes will also suffer the greatest consequences of the measures we are taking to stop the pandemic. They are more likely to be laid off or lose income12 because businesses close or because their jobs simply do not allow remote work. They may experience delayed health care for other (and highly prevalent) chronic diseases like hypertension and diabetes because routine visits to health care providers are being cancelled or because the health centers they depend on are cutting back services. 13 Their housing conditions may increase adverse mental health impacts of social distancing. All these things will not only make the pandemic worse (more cases and more severe disease), they may also magnify the burden of other health problems. At the same time the poor may also benefit from some of the hidden benefits, like reductions in air pollution, in traffic and in violence. The bottom line is that the pandemic has made even more visible the fact that health depends to a large extent on factors outside the health care system: income, racism, employment and work conditions among others. These factors, sometimes referred to as “the social determinants of health,”14 are rooted in social and economic structures, and have been fundamental drivers of many epidemics, including AIDS in the 1980s, the opioid epidemic in the 2010s (“deaths of despair”), and will today strongly affect the impact of COVID-19.

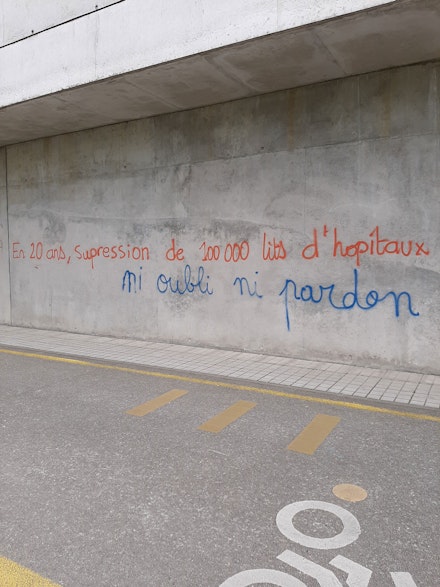

The big question is of course what will come after this. Based on what we know so far, this virus will not go away anytime soon, and a vaccine will not be available for many months, some say years (although remarkable efforts are being made to accelerate the process). Treatments (if they are identified) are not an efficient solution to reducing population transmission. How and when will social distancing be lifted? It appears that the most likely scenario is a combination of selective relaxation of social distancing (based on risk of severe disease) coupled with a much more intense effort at disease surveillance, case identification and contact tracing. But this will require significant investment in public health infrastructure (which has a long history of inadequate financing and repeated cuts, even in a rich country like the United States).15

Of course, globally a major question is what will happen when the pandemic fully reaches lower- and middle-income countries. Many of these countries have also adopted stay at home orders, without necessarily considering their full implications. Large proportions of populations in these countries have limited access to water and live in slums where social distancing is impossible (and where stay at home orders can have dramatic adverse consequences). There have already been reports of mass migrations16 returning to rural area from the cities in India for example. Many of these populations work in the informal economy. Will stay at home orders be used by governments to quell social protests and repress political movements? How will the global economic recession affect these countries? There are already emerging signs that food supply chains could be affected. What about increasing social unrest if stay-at-home orders and curfews are maintained? How will the fragile and very minimal health and public health systems of these countries deal with this? Will all populations have equal access to the vaccine once we have one? How much will it cost and who will pay?

The truth is that it is impossible to predict at this time what the ultimate health impact of the pandemic will be and how will it compare to other health problems averted or created by our response. There will be much for social scientists and public health researchers to describe, analyze and fully understand. There will be debates (many already occurring) on whether we did or did not act informed by science and whether the response is a success or a radical failure17 of science driven policy and international cooperation (it’s probably a mixture of all of this…). But will we learn anything from this? Will we see that grand scale changes are actually possible? Will we see that the system we live in with its inequities, health threats, and environmental impacts (these things are related, as some have traced the origins of the virus to environmental degradation)18 is nothing “natural” but rather something of our own making? Many of you will say we will not, and you may be right, but indulge me for a minute. Perhaps this crisis will open our eyes and make starkly visible what has been there all along…Chances for significant change are slim, and yes, many structural factors remain untouched, but we have never seen anything like this: a global economy stopped to protect health, an end to frantic global travel, dramatic reductions in air pollution and carbon emissions (“the steepest annual fall in C02 in history”),19 inmates who should never have been incarcerated being released, unprecedented (albeit admittedly very minimal) wealth redistribution via direct payments in times when most of us would have said the likelihood of this happening was zero. Call me a naïve optimist, but despite the hardship and the chaos, some of the things the pandemic has triggered give me a glimmer of hope.

- www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/mar/31/new-york-andrew-cuomo-coronavirus-ventilators

- www.cnbc.com/2020/03/24/italian-coronavirus-cases-seen-10-times-higher-than-official-tally.html

- www.who.int/gho/phe/outdoor_air_pollution/burden_text/en/

- www.cdc.gov/injury/features/global-road-safety/index.html

- www.healthdata.org/infographic/firearm-deaths-around-world-1990%E2%80%932016

- www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/10/upshot/coronavirus-deaths-new-york-city.html

- www.nytimes.com/2020/04/07/us/coronavirus-race.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1446809/

- https://www.apa.org/research/action/immune

- www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20180817.901935/full/"

- www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsb2005114

- www.nytimes.com/2020/03/20/us/coronavirus-poverty-school-lunch.html

- www.nytimes.com/2020/04/04/us/coronavirus-community-clinics-seattle.html

- www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218

- www.nytimes.com/2020/03/14/us/coronavirus-health-departments.html

- https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/27/india/coronavirus-covid-19-india-2703-intl-hnk/index.html

- www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/09/deadly-virus-britain-failed-prepare-mers-sars-ebola-coronavirus?CMP=share_btn_tw

- www.isglobal.org/en/healthisglobal/-/custom-blog-portlet/salud-planetaria-y-covid-19-la-degradacion-ambiental-como-el-origen-de-la-pandemia-actual/6112996/0

- www.greenbiz.com/article/coronavirus-could-trigger-largest-ever-annual-fall-co2-2020

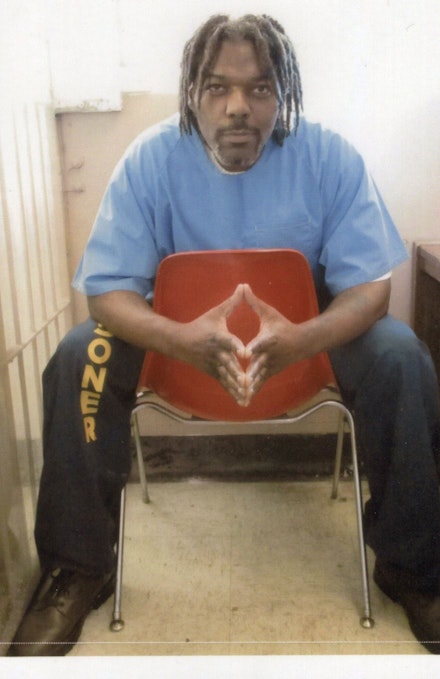

Tim Young. Photo: San Quentin Prison.

Tim Young. Photo: San Quentin Prison.