On the frosty morning of Dec. 9, 1921, in Dayton, Ohio, researchers at a General Motors lab poured a new fuel blend into one of their test engines. Immediately, the engine began running more quietly and putting out more power.

The new fuel was tetraethyl lead. With vast profits in sight – and very few public health regulations at the time – General Motors Co. rushed gasoline diluted with tetraethyl lead to market despite the known health risks of lead. They named it “Ethyl” gas.

It has been 100 years since that pivotal day in the development of leaded gasoline. As a historian of media and the environment, I see this anniversary as a time to reflect on the role of public health advocates and environmental journalists in preventing profit-driven tragedy.

Scientists working for General Motors discovered that tetraethyl lead could greatly improve the efficiency and longevity of engines in the 1920s. Courtesy of General Motors Institute.

Lead and death

By the early 1920s, the hazards of lead were well known – even Charles Dickens and Benjamin Franklin had written about the dangers of lead poisoning.

When GM began selling leaded gasoline, public health experts questioned its decision. One called lead a serious menace to public health, and another called concentrated tetraethyl lead a “malicious and creeping” poison.

General Motors and Standard Oil waved the warnings aside until disaster struck in October 1924. Two dozen workers at a refinery in Bayway, New Jersey, came down with severe lead poisoning from a poorly designed GM process. At first they became disoriented, then burst into insane fury and collapsed into hysterical laughter. Many had to be wrestled into straitjackets. Six died, and the rest were hospitalized. Around the same time, 11 more workers died and several dozen more were disabled at similar GM and DuPont plants across the U.S.

The news media began to criticize Standard Oil and raise concerns over Ethyl gas with articles and cartoons. New York Evening Journal via The Library of Congress.

Fighting the media

The auto and gas industries’ attitude toward the media was hostile from the beginning. At Standard Oil’s first press conference about the 1924 Ethyl disaster, a spokesman claimed he had no idea what had happened while advising the media that “Nothing ought to be said about this matter in the public interest.”

More facts emerged in the months after the event, and by the spring of 1925, in-depth newspaper coverage started to appear, framing the issue as public health versus industrial progress. A New York World article asked Yale University gas warfare expert Yandell Henderson and GM’s tetraethyl lead researcher Thomas Midgley whether leaded gasoline would poison people. Midgley joked about public health concerns and falsely insisted that leaded gasoline was the only way to raise fuel power. To demonstrate the negative impacts of leaded fuel, Henderson estimated that 30 tons of lead would fall in a dusty rain on New York’s Fifth Avenue every year.

Industry officials were outraged over the coverage. A GM public relations history from 1948 called the New York World’s coverage “a campaign of publicity against the public sale of gasoline containing the company’s antiknock compound.” GM also claimed that the media labeled leaded gas “loony gas” when, in fact, it was the workers themselves who named it as such.

Leaded gas was marketed as Ethyl, a joint brand of Standard Oil and General Motors. John Margolies/Library of Congress.

Attempts at regulation

In May 1925, the U.S. Public Health Service asked GM, Standard Oil and public health scientists to attend an open hearing on leaded gasoline in Washington. The issue, according to GM and Standard, involved refinery safety, not public health. Frank Howard of Standard Oil argued that tetraethyl lead was diluted at over 1,000 to 1 in gasoline and therefore posed no risk to the average person.

Public health scientists challenged the need for leaded gasoline. Alice Hamilton, a physician at Harvard, said, “There are thousands of things better than lead to put in gasoline.” And she was right. There were plenty of well-known alternatives at the time, and some were even patented by GM. But no one in the press knew how to find that information, and the Public Health Service, under pressure from the auto and oil industries, canceled a second day of public hearings that would have discussed safer gasoline additives like ethanol, iron carbonyl and catalytic reforming.

By 1926, the Public Health Service announced that they had “no good reason” to prohibit leaded gasoline, even though internal memos complained that their research was “half baked.”

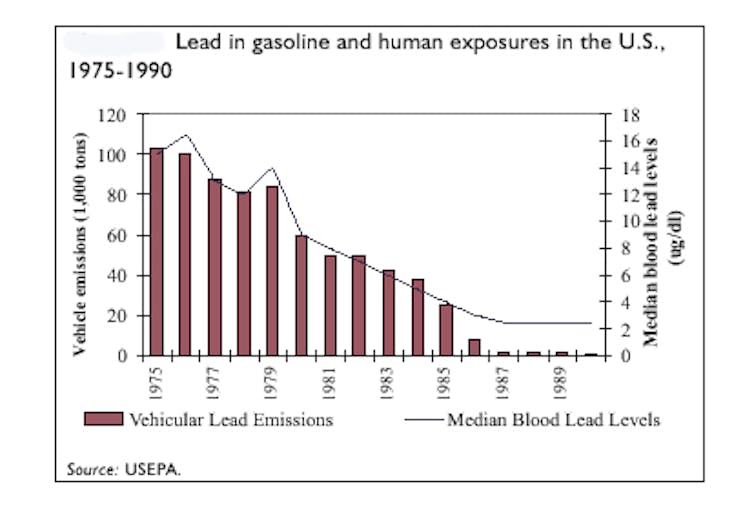

As leaded gasoline fell out of use, lead levels in people’s blood fell as well. U.S. EPA.

The rise and fall of leaded gasoline

Leaded gasoline went on to dominate fuel markets worldwide. Researchers have estimated that decades of burning leaded gasoline caused millions of premature deaths, enormous declines in IQ levels and many other associated social problems.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the public health case against leaded gasoline reemerged. A California Institute of Technology geochemist, Clair Cameron Patterson, was finding it difficult to measure lead isotopes in his laboratory because lead from gasoline was everywhere and his samples were constantly being contaminated. Patterson created the first “clean room” to carry on his isotope work, but he also published a 1965 paper, “Contaminated and Natural Lead Environments of Man,” and said that “the average resident of the U.S. is being subjected to severe chronic lead insult.”

In parallel, by the 1970s, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency decided that leaded gasoline had to be phased out eventually because it clogged catalytic converters on cars and led to more air pollution. Leaded gasoline manufacturers objected, but the objections were overruled by an appeals court.

The public health concerns continued to build in the 1970s and 1980s when University of Pittsburgh pediatrician Herbert Needleman ran studies linking high levels of lead in children with low IQ and other developmental problems. Both Patterson and Needleman faced strong partisan attacks from the lead industry, which claimed that their research was fraudulent.

Both were eventually vindicated when, in 1996, the U.S. officially banned the sale of leaded gasoline for public health reasons. Europe was next in the 2000s, followed by developing nations after that. In August 2021, the last country in the world to sell leaded gas, Algeria, banned it.

A century of leaded gasoline has taken millions of lives and to this day leaves the soil in many cities from New Orleans to London toxic.

The leaded gasoline story provides a practical example of how industry’s profit-driven decisions – when unsuccessfully challenged and regulated – can cause serious and long-term harm. It takes individual public health leaders and strong media coverage of health and environmental issues to counter these risks.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.