Most Americans view mainline religious groups favorably, survey says

By Matt Bernardini

A new report from Pew Research says that most Americans view large religious groups favorably. Photo by Africa Studio/Shutterstock

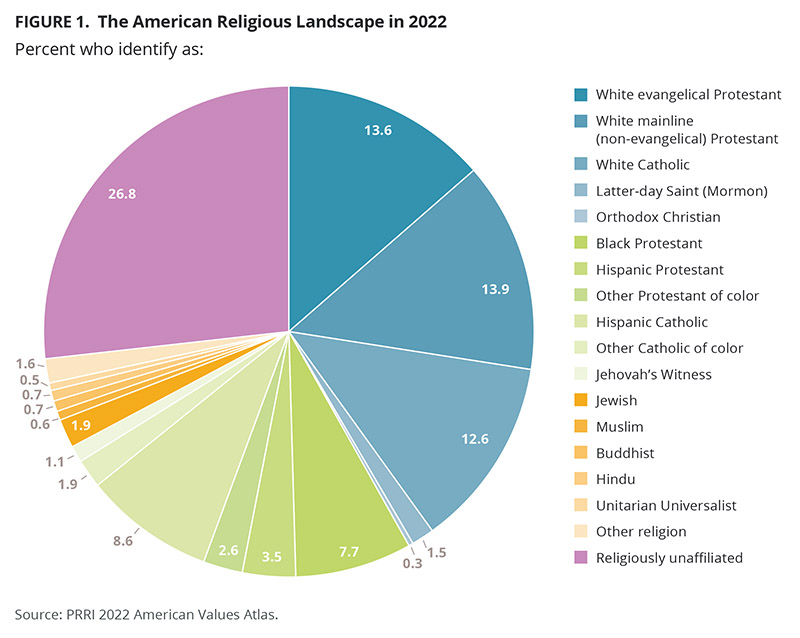

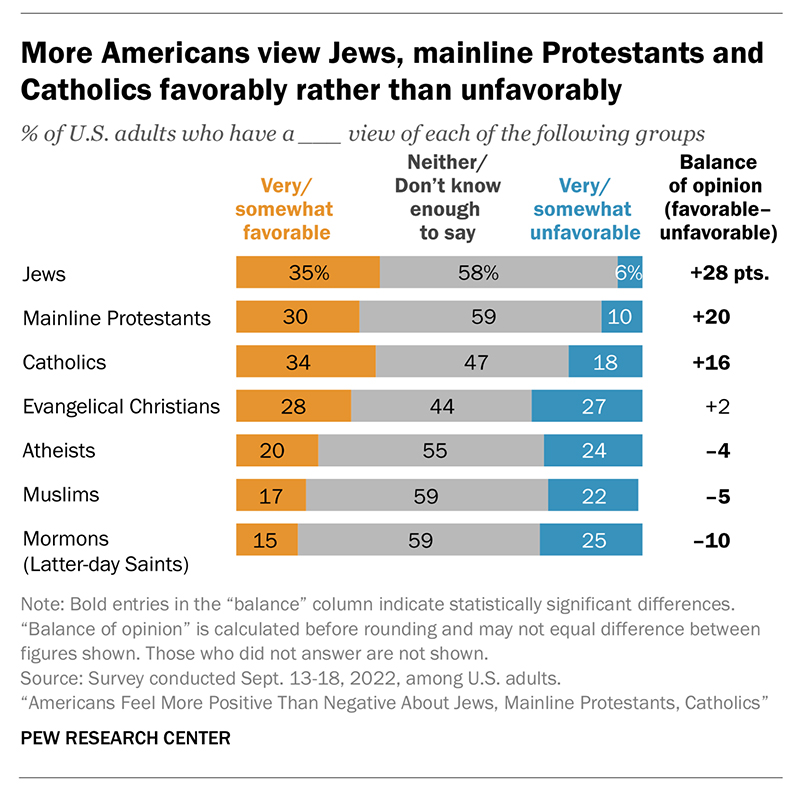

March 15 (UPI) -- Americans hold a favorable view of some of the country's largest religious groups but have a negative view of Muslims, according to a new poll by Pew Research.

Thirty-five percent of poll respondents said that they had a somewhat or very favorable view of Jews, while just 6% said they had an unfavorable view. Fifty-eight percent of people said they had neither.

Protestants also had a net favorability rating of 20 points, and Catholics had a net favorability rating of 16 points. However, these groups are also largely represented as Pew notes.

"The patterns are affected in part by the size of the groups asked about, since people tend to rate their own religious group positively," the Pew report said. "This means that the largest groups -- such as Catholics and evangelical Christians -- get a lot of favorable ratings just from their own members."

However, just 17 percent of Americans have a favorable view of Muslims, compared with 22 percent of Americans who have an unfavorable view. Only Mormons were rated more unfavorably, with a net unfavorability rating of 10 points.

Americans also have an unfavorable view of atheists, even though more people today say they know atheists.

"In 2019, 65% of Americans reported that they knew an atheist; in the new survey, 71% say the same," Pew said

Overall Pew found that, knowing someone who is from a particular group, leads people to have a more positive view of that group as a whole.

"Across the board, those who know someone from a religious group (but are not members of that group themselves) are more likely than those who do not know someone in the group to offer an opinion of the group -- and usually to express more positive feelings," Pew said.

Americans like Jews, Catholics and mainline Protestants. Evangelicals, not so much.

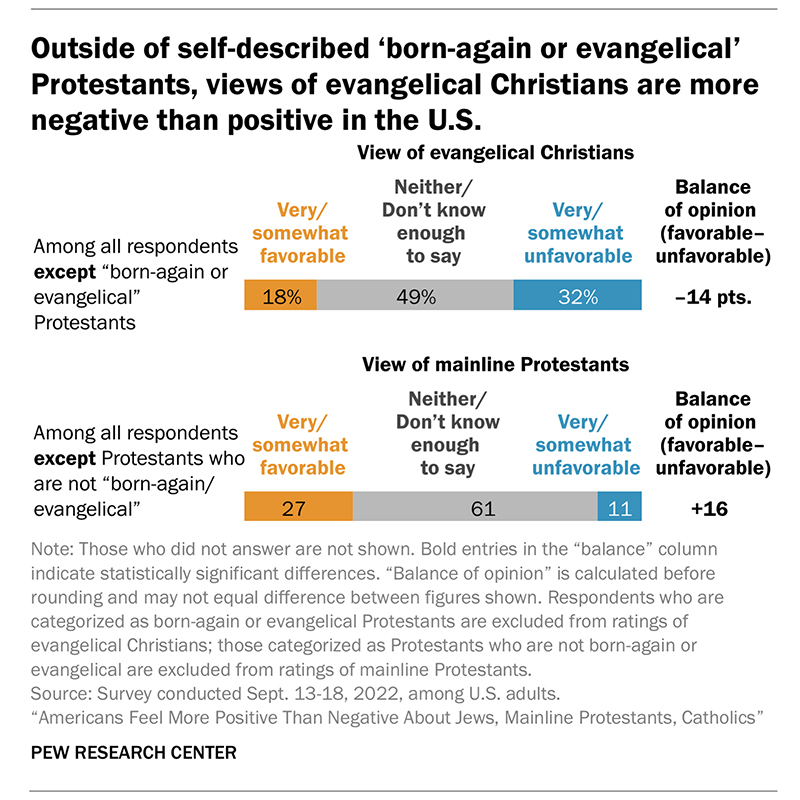

A new Pew Research poll finds that only 18% of nonevangelical Americans had favorable opinions of evangelicals; 32% had somewhat unfavorable views.

Image by David Peterson/Pixabay/Creative Commons

(RNS) — What do most Americans think of faiths not their own?

Not much.

That’s according to a new Pew Research survey that asked 10,588 Americans if they had positive or negative feelings toward other faiths. Between 40% and 60% answered “neither favorable nor unfavorable” or “don’t know enough to say.”

“It may speak to people not liking to rate entire groups of people,” said Patricia Tevington, the lead researcher. ”Maybe there’s some fear of stereotyping.”

But some religious groups ranked higher in Americans’ estimations. Jews, for example, scored fairly positively: 35% of Americans expressed a very or somewhat favorable attitude toward Jews, with only 6% expressing an unfavorable attitude. Catholics, too, got good marks (34% favorable vs. 18% unfavorable), as did mainline or ecumenical Protestants (30% favorable vs. 10% unfavorable).

“More Americans view Jews, mainline Protestants and Catholics favorably rather than unfavorably” Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center

Atheists and Muslims scored overall negative views. At the bottom of the list? Latter-day Saints, or Mormons. Only 15% of Americans had a favorable opinion of Mormons, while 25% said they had unfavorable views of them.

As for evangelicals, Americans were divided: 28% had favorable opinions of evangelicals while 27% had negative opinions (44% felt they didn’t know enough to say). But as the study points out, there’s a big difference between the way evangelicals are rated by all Americans (including roughly 20% of U.S. adults who describe themselves as evangelicals) and the way they are rated by Americans who are not evangelicals.

That’s because most religious groups rate themselves highly, including 60% of evangelicals who have favorable opinions of themselves. But when evangelicals were excluded from the question, only 18% of Americans had favorable opinions of this group; 32% had somewhat unfavorable views (49% didn’t register an opinion).

By contrast, mainline or ecumenical Protestants are viewed far more positively than negatively (only 11% of nonmainline Protestants viewed this religious group unfavorably).

“Outside of self-described ‘born-again or evangelical’ Protestants, views of evangelical Christians are more negative than positive in the U.S.” Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center

Political partisanship may explain why evangelicals are viewed negatively by non evangelicals. The overwhelming majority of evangelicals identify with the Republican Party and this bloc is usually highly correlated with the so-called religious right.

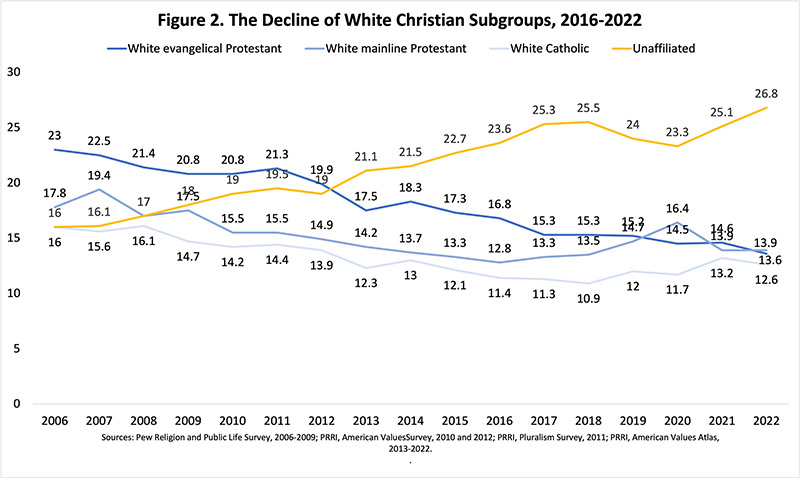

RELATED: Five charts that explain the desperate turn to MAGA among conservative white Christians

Democrats and Democratic leaners, the survey found, view evangelicals much more negatively — nearly half (47%) had an unfavorable view of evangelicals. Only 14% of nonevangelical Republicans had unfavorable views of evangelicals, by comparison.

Evangelicals aside, Americans’ views of other faiths may be influenced by whether they personally know people of other faiths, the study concludes. Some 88% of Americans know someone who is Catholic, for example. But few personally know a Muslim or a Mormon, which may account for why they view these groups negatively. (The balance of nonevangelical opinions toward evangelicals is the exception; it was negative regardless of people’s personal familiarity.)

The survey found that an increasing number of Americans personally know an atheist. In 2019, 65% of Americans reported they knew an atheist. By 2022, it was 71%. That may account for why Americans view atheists has moderated somewhat and why Muslims and Mormons are viewed less favorably.

“There’s a big distinction on whether or not you know someone of that religious group,” Tevington said. “That tends to increase favorability.”

The survey had a margin of error of plus or minus 1.5 percentage points.

RELATED: 3 big numbers that tell the story of secularization in America