Florida dolphin found with highly pathogenic avian flu: Report

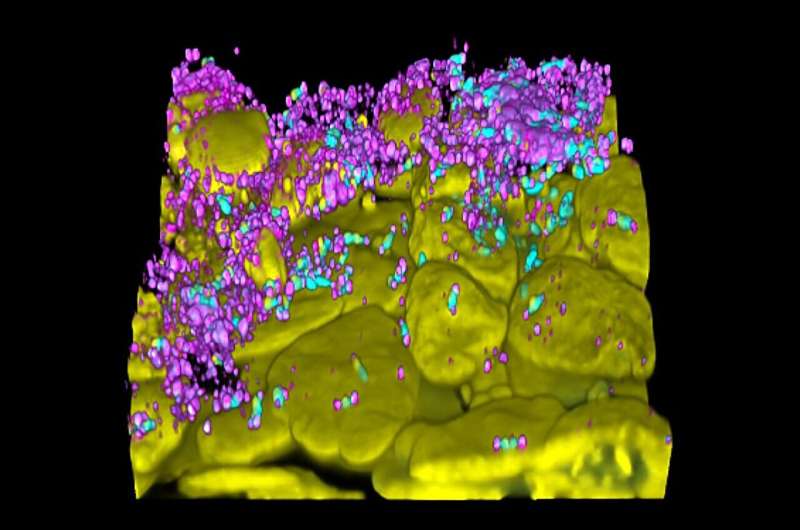

The case of a Florida bottlenose dolphin found with highly pathogenic avian influenza virus, or HPAIV—a discovery made by University of Florida researchers in collaboration with multiple other agencies and one of the first reports of a constantly growing list of mammals affected by this virus—has been published in Communications Biology

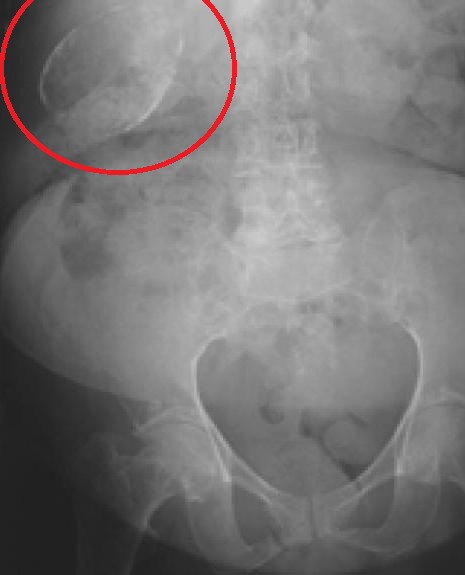

The report documents the discovery, the first finding of HPAIV in a cetacean in North America, from the initial response by UF's Marine Animal Rescue team to a report of a distressed dolphin in Dixie County, Florida, to the subsequent identification of the virus from brain and tissue samples obtained in a postmortem examination.

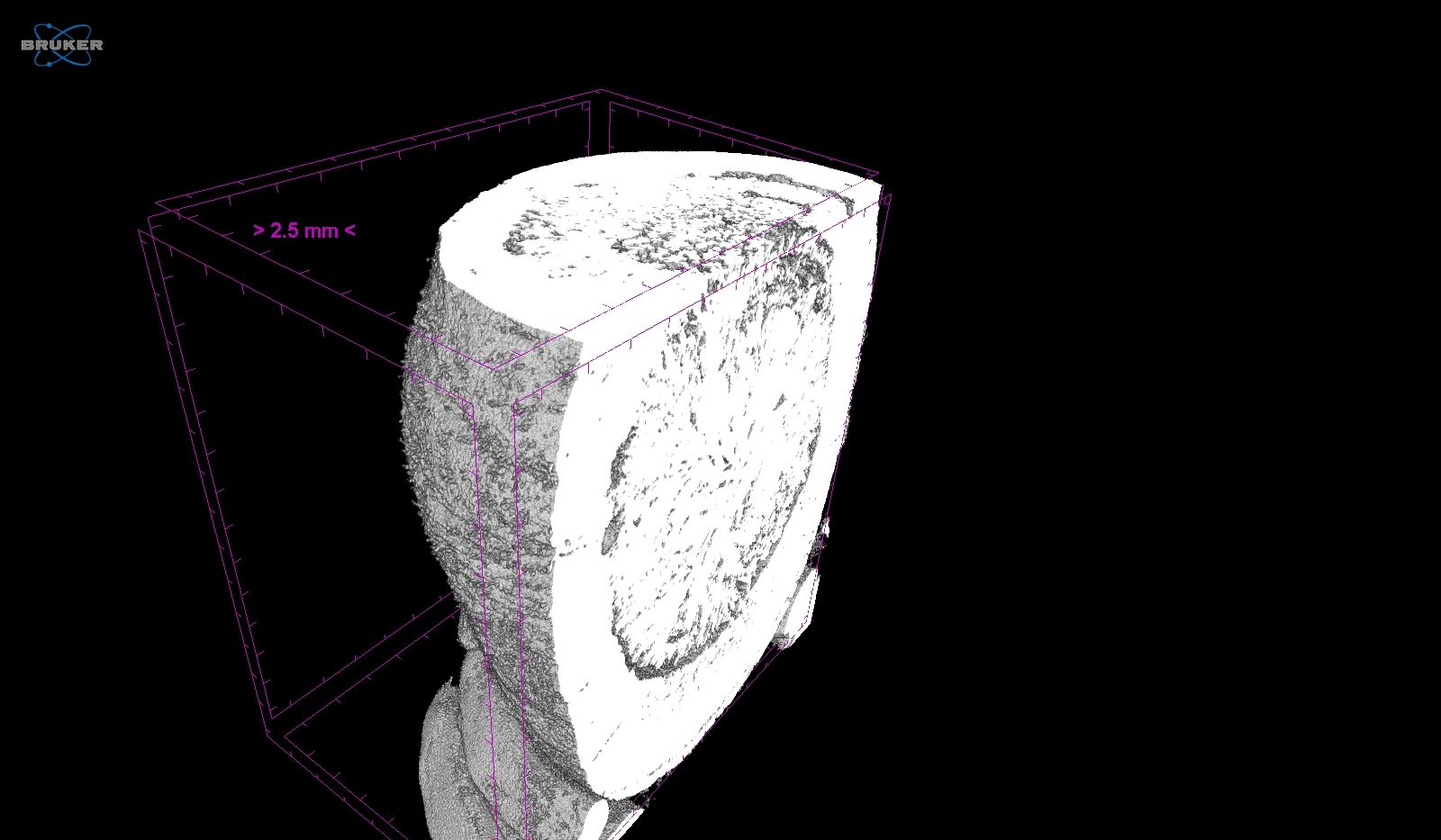

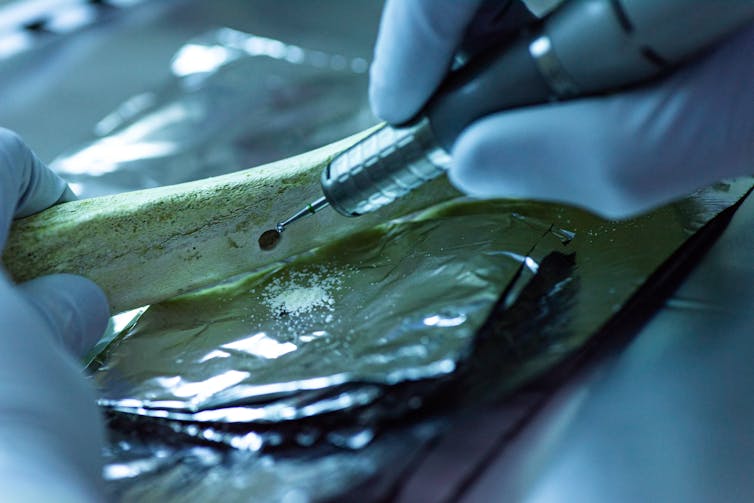

Analyses initially performed at UF's zoological medicine diagnostic laboratory ruled out the presence of other potential agents at play in the dolphin's disease, with the Bronson Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory in Kissimmee, Florida, verifying the presence of HPAI virus in both the lung and brain.

Those results were confirmed by the National Veterinary Services Laboratory in Ames, Iowa, which characterized the virus subtype and pathotype. The virus was confirmed to be HPAI A (H5N1) virus of HA clade 2.3.4.4b. Subsequent tissue analysis was performed at the Biosafety Level 3 enhanced laboratory at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in Memphis.

Allison Murawski, D.V.M., a former intern with UF's aquatic animal medicine program, was first author on the study and developed a case report on the dolphin as part of her research project. She traveled to Memphis and worked closely with Richard Webby, Ph.D., who directs the World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals and Birds at St. Jude's and served as corresponding author on the paper

Webby's laboratory investigates avian influenza cases in many species and was key in determining where the virus may have originated, what unique RNA characteristics or mutations were present that could suggest its ability to infect other mammals, and how the virus could be tracked from this source.

The researchers sequenced the genomes from local birds and looked at viruses isolated from Northeast seal populations.

"We still don't know where the dolphin got the virus and more research needs to be done," Webby said.

"This investigation was an important step in understanding this virus and is a great example where happenstance joins with curiosity, having to answer the 'why' and then seeing how the multiple groups and expertise took this to a fantastic representation of collaborative excellence," said Mike Walsh, D.V.M., an associate professor of aquatic animal health, who served as Murawski's faculty mentor.

More information: Allison Murawski et al, Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus in a common bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) in Florida, Communications Biology (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s42003-024-06173-x

Journal information: Communications Biology

Provided by University of Florida Experts warn bird flu virus changing rapidly in largest ever outbreak

Florida dolphin found with highly pathogenic avian flu: Report

UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA

The case of a Florida bottlenose dolphin found with highly pathogenic avian influenza virus, or HPAIV — a discovery made by University of Florida researchers in collaboration with multiple other agencies and one of the first reports of a constantly growing list of mammals affected by this virus — has been published in Communications Biology.

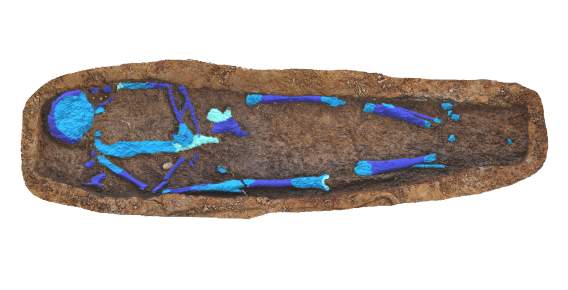

The report documents the discovery, the first finding of HPAIV in a cetacean in North America, from the initial response by UF’s Marine Animal Rescue team to a report of a distressed dolphin in Dixie County, Florida, to the subsequent identification of the virus from brain and tissue samples obtained in a postmortem examination.

Analyses initially performed at UF’s zoological medicine diagnostic laboratory ruled out the presence of other potential agents at play in the dolphin’s disease, with the Bronson Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory in Kissimmee, Florida, verifying the presence of HPAI virus in both the lung and brain.

Those results were confirmed by the National Veterinary Services Laboratory in Ames, Iowa, which characterized the virus subtype and pathotype. The virus was confirmed to be HPAI A (H5N1) virus of HA clade 2.3.4.4b. Subsequent tissue analysis was performed at the Biosafety Level 3 enhanced laboratory at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis.

Allison Murawski, D.V.M., a former intern with UF’s aquatic animal medicine program, was first author on the study and developed a case report on the dolphin as part of her research project. She traveled to Memphis and worked closely with Richard Webby, Ph.D., who directs the World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals and Birds at St. Jude’s and served as corresponding author on the paper

Webby’s laboratory investigates avian influenza cases in many species and was key in determining where the virus may have originated, what unique RNA characteristics or mutations were present that could suggest its ability to infect other mammals, and how the virus could be tracked from this source.

The researchers sequenced the genomes from local birds and looked at viruses isolated from Northeast seal populations.

“We still don’t know where the dolphin got the virus and more research needs to be done,” Webby said.

“This investigation was an important step in understanding this virus and is a great example where happenstance joins with curiosity, having to answer the ‘why’ and then seeing how the multiple groups and expertise took this to a fantastic representation of collaborative excellence,” said Mike Walsh, D.V.M., an associate professor of aquatic animal health, who served as Murawski’s faculty mentor.

JOURNAL

Communications Biology

METHOD OF RESEARCH

Case study

SUBJECT OF RESEARCH

Animals

ARTICLE TITLE

Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus in a common bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) in Florida

ARTICLE PUBLICATION DATE

18-Apr-2024