The Founder of Cosmic Inflation Theory on Cosmology's Next Big Ideas

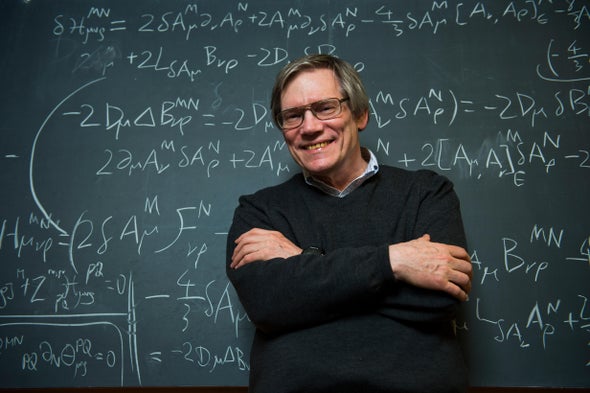

Physicist Alan Guth, the father of cosmic inflation theory, describes emerging ideas about where our universe comes from, what else is out there, and what caused it to exist in the first place.

This article was produced for Kavli Prize by Scientific American Custom Media, a division separate from the magazine's board of editors.

Credit: Deanne Fitzmaurice/National Geographic Image Collection/Alamy

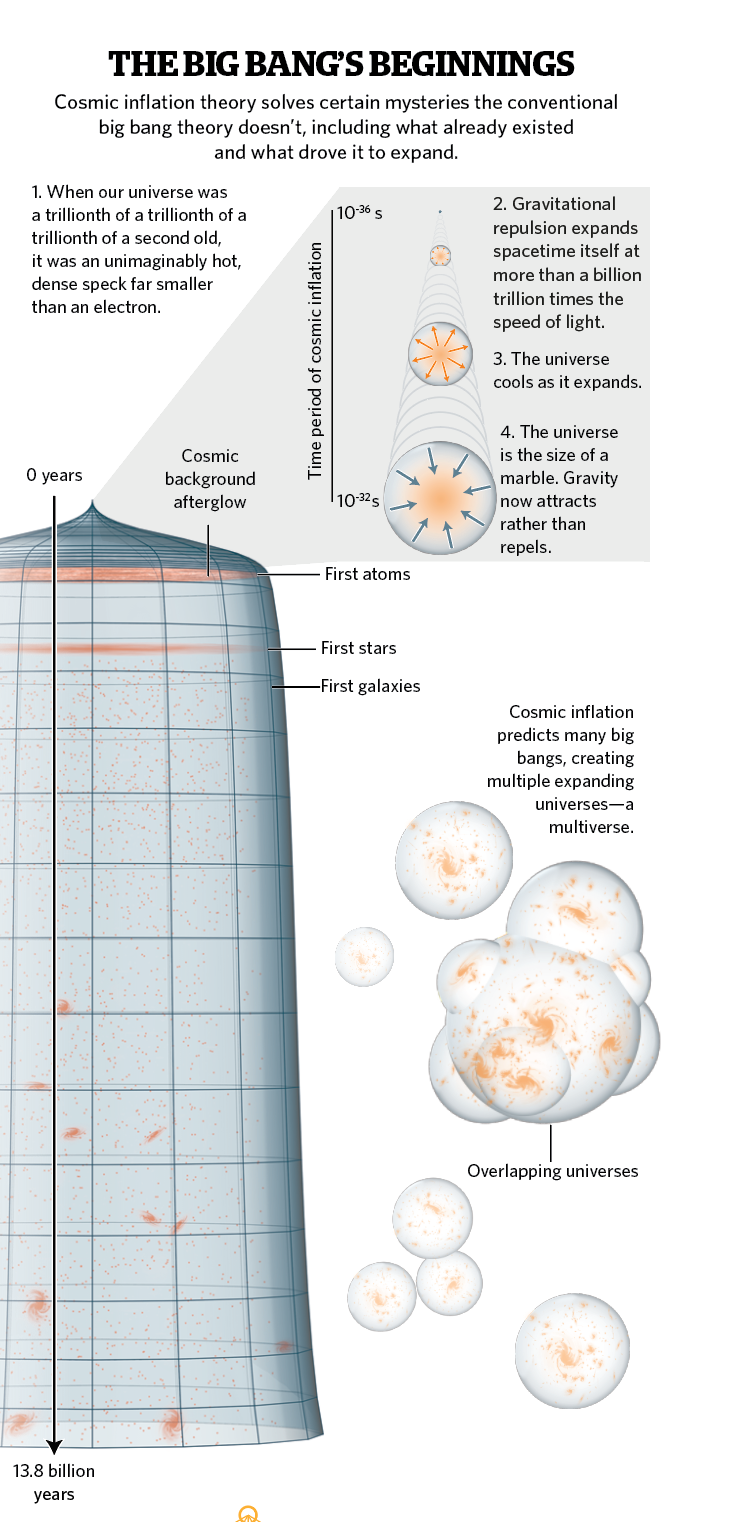

Our universe began with a bang—a big bang. The explosion stretched the very fabric of spacetime, sending superheated matter in all directions. As it expanded, the matter cooled and started to aggregate, forming atoms, then elements, then stars, galaxies and, ultimately, all we know and see today

For physicist and cosmologist Alan Guth, one big question about the big bang remains: “What was it that banged?”

The answer lies in his theory of cosmic inflation. “It sets up the conditions for the big bang—like a prequel,” says Guth, a professor of physics at MIT. For developing that theory, Guth and two of his colleagues, Andrei Linde at Stanford University and Alexei Starobinsky at the Landau Institute for Theoretical Physics of the Russian Academy of Sciences near Moscow, were awarded the 2014 Kavli Prize in astrophysics.

According to the theory, for less than a millionth of a trillionth of a trillionth of a second after the universe's birth, an exotic form of matter exerted a counterintuitive force: gravitational repulsion. Although we normally think of gravity as being attractive (picture Isaac Newton and the falling apple), Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity allows for such a force.

Under the conditions present in the early universe, when temperatures were extraordinarily high, Guth says the existence of this material was reasonably likely. “It only has to be a speck,” he says. “But when that speck starts to inflate, the expansion is exponential.”

Contemplating those fateful events—and what happened next—Guth says, raises some of the most fascinating questions in science: How did our universe begin, where is it going, and what caused it to exist in the first place

“We don’t necessarily expect to answer those questions next year,” he adds. But “anything that makes small steps towards understanding the answers is thrilling.”

Here, Guth addresses some of those mysteries, including where our universe comes from, what else is out there, and how inflation may have spawned primordial black holes, a hypothetical entity that could represent the universe’s long sought-after dark matter.

What was there before inflation started?

That is something I have been thinking about in the context of a paper that I’m writing with Sean Carroll [at Caltech]. The idea is that the universe is actually eternal. It existed at all times, so there is no beginning to explain. The laws of physics themselves don’t seem to make any significant distinction between the future and the past. As the universe evolves, its entropy, or disorder, will grow. What we call the future is simply the direction of higher entropy; a state of lower entropy is what we call the past. But a curious thing happens if you take this initial low entropy state and follow it backwards in time, towards what we previously called the past: the entropy will also start to grow in that direction. I think that the people living [along that arrow of time] would not feel anything different from what we feel. Everybody will think that they’re living from the past towards the future, except what they call the future will be what we call the past.

Our universe began with a bang—a big bang. The explosion stretched the very fabric of spacetime, sending superheated matter in all directions. As it expanded, the matter cooled and started to aggregate, forming atoms, then elements, then stars, galaxies and, ultimately, all we know and see today

For physicist and cosmologist Alan Guth, one big question about the big bang remains: “What was it that banged?”

The answer lies in his theory of cosmic inflation. “It sets up the conditions for the big bang—like a prequel,” says Guth, a professor of physics at MIT. For developing that theory, Guth and two of his colleagues, Andrei Linde at Stanford University and Alexei Starobinsky at the Landau Institute for Theoretical Physics of the Russian Academy of Sciences near Moscow, were awarded the 2014 Kavli Prize in astrophysics.

According to the theory, for less than a millionth of a trillionth of a trillionth of a second after the universe's birth, an exotic form of matter exerted a counterintuitive force: gravitational repulsion. Although we normally think of gravity as being attractive (picture Isaac Newton and the falling apple), Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity allows for such a force.

Under the conditions present in the early universe, when temperatures were extraordinarily high, Guth says the existence of this material was reasonably likely. “It only has to be a speck,” he says. “But when that speck starts to inflate, the expansion is exponential.”

Contemplating those fateful events—and what happened next—Guth says, raises some of the most fascinating questions in science: How did our universe begin, where is it going, and what caused it to exist in the first place

“We don’t necessarily expect to answer those questions next year,” he adds. But “anything that makes small steps towards understanding the answers is thrilling.”

Here, Guth addresses some of those mysteries, including where our universe comes from, what else is out there, and how inflation may have spawned primordial black holes, a hypothetical entity that could represent the universe’s long sought-after dark matter.

What was there before inflation started?

That is something I have been thinking about in the context of a paper that I’m writing with Sean Carroll [at Caltech]. The idea is that the universe is actually eternal. It existed at all times, so there is no beginning to explain. The laws of physics themselves don’t seem to make any significant distinction between the future and the past. As the universe evolves, its entropy, or disorder, will grow. What we call the future is simply the direction of higher entropy; a state of lower entropy is what we call the past. But a curious thing happens if you take this initial low entropy state and follow it backwards in time, towards what we previously called the past: the entropy will also start to grow in that direction. I think that the people living [along that arrow of time] would not feel anything different from what we feel. Everybody will think that they’re living from the past towards the future, except what they call the future will be what we call the past.

No comments:

Post a Comment