50 years on, the Vietnam moratorium campaigns remind us of a different kind of politics

May 7, 2020

Fifty years ago this month, hundreds of thousands of Australians assembled across the country to call for an end to the Vietnam War. The first of the moratorium campaigns, the demonstrations of May 8 1970 were the zenith of the anti-war movement in Australia that had been five years in the making.

The largest of the May 8 marches took place in Melbourne, confirming its status as the national capital of protest politics. An estimated 100,000 demonstrators clogged the city’s streets.

Despite scaremongering in preceding weeks by conservative politicians and large sections of the media about the threat of violence and mayhem, the event passed peacefully. Relieved and exultant, the movement’s leader, Jim Cairns, told the sea of protesters gathered in Bourke Street:

Nobody thought this could be done … The will of the people is being expressed today as it never has been before.

The moratorium movement was important in a number of ways.

First, and most obviously, it galvanised many ordinary Australians to join the protest actions, making a powerful statement about the collapse of support for the nation’s continued participation in the Vietnam conflict. Though the Liberal-Country Party government led by Prime Minister John Gorton obdurately dismissed the demonstrations and insisted they would have no material influence on its policy-making, it was no coincidence that 1970 marked the beginning of the withdrawal of Australia’s military forces from Vietnam. It was a policy reversal that mimicked the direction of the United States, which had witnessed its own massive anti-war moratorium demonstrations at the end of 1969.

Second, the demonstrations were a potent symbol of the larger culture of dissent that had flowered in the second half of the 1960s. The protests expressed a restless mood for change, and represented a key moment in the puncturing of the oppressive Cold War atmosphere that had dominated Australian public life for some two decades.

One contemporary observer of the moratorium marches captured their confounding spirit of anti-authoritarianism by referencing Bob Dylan:

Because something is happening here, but you don’t know what it is, do you, Mister Jones?

Two years later, much of the yearning for change would be channelled back into institutional politics with the election of the Whitlam Labor government. But in 1970, the streets had become a major outlet for political expression.

Fifty years ago this month, hundreds of thousands of Australians assembled across the country to call for an end to the Vietnam War. The first of the moratorium campaigns, the demonstrations of May 8 1970 were the zenith of the anti-war movement in Australia that had been five years in the making.

The largest of the May 8 marches took place in Melbourne, confirming its status as the national capital of protest politics. An estimated 100,000 demonstrators clogged the city’s streets.

Despite scaremongering in preceding weeks by conservative politicians and large sections of the media about the threat of violence and mayhem, the event passed peacefully. Relieved and exultant, the movement’s leader, Jim Cairns, told the sea of protesters gathered in Bourke Street:

Nobody thought this could be done … The will of the people is being expressed today as it never has been before.

The moratorium movement was important in a number of ways.

First, and most obviously, it galvanised many ordinary Australians to join the protest actions, making a powerful statement about the collapse of support for the nation’s continued participation in the Vietnam conflict. Though the Liberal-Country Party government led by Prime Minister John Gorton obdurately dismissed the demonstrations and insisted they would have no material influence on its policy-making, it was no coincidence that 1970 marked the beginning of the withdrawal of Australia’s military forces from Vietnam. It was a policy reversal that mimicked the direction of the United States, which had witnessed its own massive anti-war moratorium demonstrations at the end of 1969.

Second, the demonstrations were a potent symbol of the larger culture of dissent that had flowered in the second half of the 1960s. The protests expressed a restless mood for change, and represented a key moment in the puncturing of the oppressive Cold War atmosphere that had dominated Australian public life for some two decades.

One contemporary observer of the moratorium marches captured their confounding spirit of anti-authoritarianism by referencing Bob Dylan:

Because something is happening here, but you don’t know what it is, do you, Mister Jones?

Two years later, much of the yearning for change would be channelled back into institutional politics with the election of the Whitlam Labor government. But in 1970, the streets had become a major outlet for political expression.

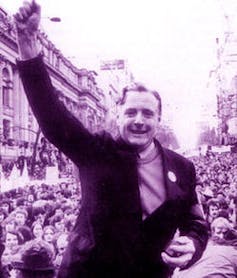

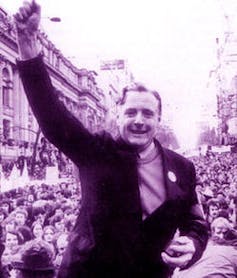

Vietnam moratorium march in Melbourne, May 8 1970. Australian Living Peace Museum

Third, the success of the May 1970 moratorium was a watershed in legitimising protest in this country. As the anti-war movement developed from the mid-1960s, it found its activities circumscribed by provisions of the Commonwealth Crimes Act, state laws and local government regulations that severely constrained the right to demonstrate. Under the terms of a Melbourne City by-law, for example, it was illegal to hand out leaflets in city streets.

In that context, the moratorium’s mass occupation tactics struck a mighty blow for the right to public protest and enlarged the space for democratic action. Indeed, it is no exaggeration to say that demonstrators since, regardless of their cause, have been benefactors of the legacy created by the moratorium campaigners of the early 1970s.

Fourth, the leadership exercised by Cairns was remarkable and unique. Because he became a figure of derision over the circumstances that ended his ministerial career in the Whitlam government in 1975, it is easy to overlook what Cairns achieved as the spiritual leader of Australia’s anti-Vietnam War movement. He was that rare thing: a politician who managed to straddle the parliamentary and extra-parliamentary spheres. Perhaps the nearest parallel in more recent times has been the former Greens leader Bob Brown.

Third, the success of the May 1970 moratorium was a watershed in legitimising protest in this country. As the anti-war movement developed from the mid-1960s, it found its activities circumscribed by provisions of the Commonwealth Crimes Act, state laws and local government regulations that severely constrained the right to demonstrate. Under the terms of a Melbourne City by-law, for example, it was illegal to hand out leaflets in city streets.

In that context, the moratorium’s mass occupation tactics struck a mighty blow for the right to public protest and enlarged the space for democratic action. Indeed, it is no exaggeration to say that demonstrators since, regardless of their cause, have been benefactors of the legacy created by the moratorium campaigners of the early 1970s.

Fourth, the leadership exercised by Cairns was remarkable and unique. Because he became a figure of derision over the circumstances that ended his ministerial career in the Whitlam government in 1975, it is easy to overlook what Cairns achieved as the spiritual leader of Australia’s anti-Vietnam War movement. He was that rare thing: a politician who managed to straddle the parliamentary and extra-parliamentary spheres. Perhaps the nearest parallel in more recent times has been the former Greens leader Bob Brown.

Jim Cairns was a strong leader of the anti-Vietnam War movement. Evatt Foundation

Cairns was critical to the success of the May 8 moratorium campaign. He stoically wore the slings of the radical, younger elements of the movement who were prepared to spill blood in the name of peace, while at the same time calmly rebutting the histrionics of his conservative political opponents who equated mass demonstrations with “mob rule”.

In a parliamentary debate on the moratorium in April 1970, Cairns articulated what was described as the movement’s “manifesto of dissent”:

Some … think that democracy is just Parliament alone … But times are changing. A whole generation is not prepared to accept this complacent, conservative theory. Parliament is not democracy. It is one manifestation of democracy … Democracy is government by the people, and government by people demands action by the people … in public places all around the land.

Half a century on, it is striking how quaint these ideas seem. We have mostly retreated to practising politics as a spectator sport. This is despite the evident limits of this passivity.

Consider climate change, for example. More than a decade of relying on our political representatives for progress has yielded little more than conflict, frustration and inertia.

Notably, throughout these years of missed opportunity, none of our political leaders have emerged to emulate the role that Cairns fulfilled in the era of the Vietnam War, namely, sustaining a campaign for action on climate change both in the parliament and out in the community.

But then they were different times and Cairns, notwithstanding his later follies, was a special kind of politician.

Cairns was critical to the success of the May 8 moratorium campaign. He stoically wore the slings of the radical, younger elements of the movement who were prepared to spill blood in the name of peace, while at the same time calmly rebutting the histrionics of his conservative political opponents who equated mass demonstrations with “mob rule”.

In a parliamentary debate on the moratorium in April 1970, Cairns articulated what was described as the movement’s “manifesto of dissent”:

Some … think that democracy is just Parliament alone … But times are changing. A whole generation is not prepared to accept this complacent, conservative theory. Parliament is not democracy. It is one manifestation of democracy … Democracy is government by the people, and government by people demands action by the people … in public places all around the land.

Half a century on, it is striking how quaint these ideas seem. We have mostly retreated to practising politics as a spectator sport. This is despite the evident limits of this passivity.

Consider climate change, for example. More than a decade of relying on our political representatives for progress has yielded little more than conflict, frustration and inertia.

Notably, throughout these years of missed opportunity, none of our political leaders have emerged to emulate the role that Cairns fulfilled in the era of the Vietnam War, namely, sustaining a campaign for action on climate change both in the parliament and out in the community.

But then they were different times and Cairns, notwithstanding his later follies, was a special kind of politician.

Associate Professor of Politics, Monash University

Monash University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

We believe in the free flow of information

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons licence.Republish this article

Monash University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

We believe in the free flow of information

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons licence.Republish this article

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66779050/GettyImages_1212168407.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19948439/GettyImages_1220243530.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19954426/GettyImages_1210776136.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19954416/GettyImages_1217210567.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19954442/GettyImages_1210025771.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19948449/GettyImages_1210072417.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19948456/GettyImages_1222093363.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19948517/GettyImages_1209890190.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19948493/GettyImages_1209563214.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19948476/GettyImages_1221648310.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66708104/GettyImages_1210348504.0.jpg)