Nuclear Tests Marked Life on Earth With a Radioactive Spike

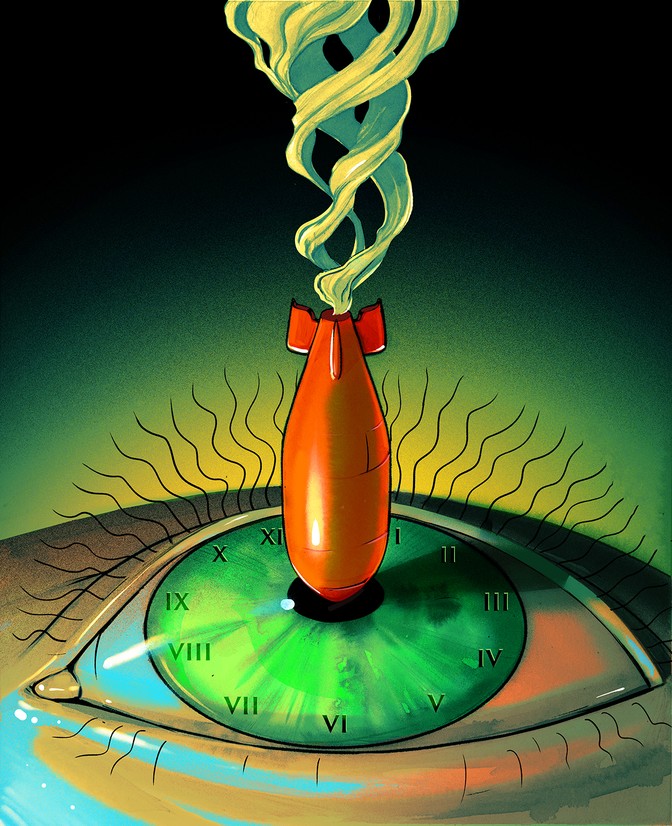

Even as it disappears, the “bomb spike” is revealing the ways humans have reshaped the planet.

Zoe van Djik

Story by Carl Zimmer

MARCH 2, 2020

On the morning of March 1, 1954, a hydrogen bomb went off in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. John Clark was only 20 miles away when he issued the order, huddled with his crew inside a windowless concrete blockhouse on Bikini Atoll. But seconds went by, and all was silent. He wondered if the bomb had failed. Eventually, he radioed a Navy ship monitoring the test explosion.

“It’s a good one,” they told him.

Then the blockhouse began to lurch. At least one crew member got seasick—“landsick” might be the better descriptor. A minute later, when the bomb blast reached them, the walls creaked and water shot out of the bathroom pipes. And then, once more, nothing. Clark waited for another impact—perhaps a tidal wave—but after 15 minutes he decided it was safe for the crew to venture outside.

The mushroom cloud towered into the sky. The explosion, dubbed “Castle Bravo,” was the largest nuclear-weapons test up to that point. It was intended to try out the first hydrogen bomb ready to be dropped from a plane. Many in Washington felt that the future of the free world depended on it, and Clark was the natural pick to oversee such a vital blast. He was the deputy test director for the Atomic Energy Commission, and had already participated in more than 40 test shots. Now he gazed up at the cloud in awe. But then his Geiger counter began to crackle.

“It could mean only one thing,” Clark later wrote. “We were already getting fallout.”

That wasn’t supposed to happen. The Castle Bravo team had been sure that the radiation from the blast would go up to the stratosphere or get carried away by the winds safely out to sea. In fact, the chain reactions unleashed during the explosion produced a blast almost three times as big as predicted—1,000 times bigger than the Hiroshima bomb.

Within seconds, the fireball had lofted 10 million tons of pulverized coral reef, coated in radioactive material. And soon some of that deadly debris began dropping to Earth. If Clark and his crew had lingered outside, they would have died in the fallout.

Clark rushed his team back into the blockhouse, but even within the thick walls, the level of radiation was still climbing. Clark radioed for a rescue but was denied: It would be too dangerous for the helicopter pilots to come to the island. The team hunkered down, wondering if they were being poisoned to death. The generators failed, and the lights winked out.

“We were not a happy bunch,” Clark recalled.

They spent hours in the hot, radioactive darkness until the Navy dispatched helicopters their way. When the crew members heard the blades, they put on bedsheets to protect themselves from fallout. Throwing open the blockhouse door, they ran to nearby jeeps as though they were in a surreal Halloween parade, and drove half a mile to the landing pad. They clambered into the helicopters, and escaped over the sea.

Read: The people who built the atomic bomb

As Clark and his crew found shelter aboard a Navy ship, the debris from Castle Bravo rained down on the Pacific. Some landed on a Japanese fishing boat 70 miles away. The winds then carried it to three neighboring atolls. Children on the island of Rongelap played in the false snow. Five days later, Rongelap was evacuated, but not before its residents had received a near-lethal dose of radiation. Some people suffered burns, and a number of women later gave birth to severely deformed babies. Decades later, studies would indicate that the residents experienced elevated rates of cancer.

Traveling the world to see microbes, plants, and animals in oceans, grasslands, forests, deserts, the icy poles—and wherever else they may be.

Read more

The shocking power of Castle Bravo spurred the Soviet Union to build up its own nuclear arsenal, spurring the Americans in turn to push the arms race close to global annihilation. But the news reports of sick Japanese fishermen and Pacific islanders inspired a worldwide outcry against bomb tests. Nine years after Clark gave the go-ahead for Castle Bravo, the United States, Soviet Union, and Great Britain signed a treaty to ban aboveground nuclear-weapons testing. As for Clark, he returned to the United States and lived for another five decades, dying in 2002 at age 98.

Among the isotopes created by a thermonuclear blast is a rare, radioactive version of carbon, called carbon 14. Castle Bravo and the hydrogen-bomb tests that followed it created vast amounts of carbon 14, which have endured ever since. A little of this carbon 14 made its way into Clark’s body, into his blood, his fat, his gut, and his muscles. Clark carried a signature of the nuclear weapons he tested to his grave.

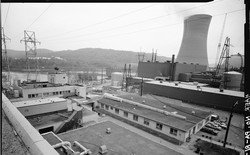

I can state this with confidence, even though I did not carry out an autopsy on Clark. I know this because the carbon 14 produced by hydrogen bombs spread over the entire world. It worked itself into the atmosphere, the oceans, and practically every living thing. As it spread, it exposed secrets. It can reveal when we were born. It tracks hidden changes to our hearts and brains. It lights up the cryptic channels that join the entire biosphere into a single network of chemical flux. This man-made burst of carbon 14 has been such a revelation that scientists refer to it as “the bomb spike.” Only now is the bomb spike close to disappearing, but as it vanishes, scientists have found a new use for it: to track global warming, the next self-inflicted threat to our survival.

Sixty-five years after Castle Bravo, I wanted to see its mark. So I drove to Cape Cod, in Massachusetts. I was 7,300 miles from Bikini Atoll, in a cozy patch of New England forest on a cool late-summer day, but Clark’s blast felt close to me in both space and time.

I made my way to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, where I met Mary Gaylord, a senior research assistant. She led me to the lounge of Maclean Hall. Outside the window, dogwoods bloomed. Next to the Keurig coffee maker was a refrigerator with the sign that read store only food in this refrigerator. We had come to this ordinary spot to take a look at something extraordinary. Next to the refrigerator was a massive section of tree trunk, as wide as a dining-room table, resting on a pallet.

The beech tree from which this slab came from was planted around 1870, by a Boston businessman named Joseph Story Fay near his summer house in Woods Hole. The seedling grew into a towering, beloved fixture in the village. Lovelorn initials scarred its broad base. And then, after nearly 150 years, it started to rot from bark disease and had to come down.

“They had to have a ceremony to say goodbye to it. It was a very sad day,” Gaylord said. “And I saw an opportunity.”

Gaylord is an expert at measuring carbon 14. Before the era of nuclear testing, carbon 14 was generated outside of labs only by cosmic rays falling from space. They crashed into nitrogen atoms, and out of the collision popped a carbon 14 atom. Just one in 1 trillion carbon atoms in the atmosphere was a carbon 14 isotope. Fay’s beech took carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere to build wood, and so it had the same one-in-a-trillion proportion.

When Gaylord got word that the tree was coming down in 2015, she asked for a cross-section of the trunk. Once it arrived at the institute, she and two college students carefully counted its rings. Looking at the tree, I could see a line of pinholes extending from the center to the edge of the trunk. Those were the places where Gaylord and her students used razor blades to carve out bits of wood. In each sample, they measured the level of radiocarbon.

“In the end, we got what I hoped for,” she said. What she’d hoped for was a history of our nuclear era.

RELATED STORIES

The 60-Year Downfall of Nuclear Power in the U.S. Has Left a Huge Mess

America's Nuclear-Waste Plan Is a Giant Mess

What Lies Beneath

For most of the tree’s life, they found, the level had remained steady from one year to the next. But in 1954, John Clark initiated an extraordinary climb. The new supply of radiocarbon atoms in the atmosphere over Bikini Atoll spread around the world. When it reached Woods Hole, Fay’s beech tree absorbed the bomb radiocarbon in its summer leaves and added it to its new ring of wood.

As nuclear testing accelerated, Fay’s beech took on more radiocarbon. A graph pinned to the wall above the beech slab charts the changes. In less than a decade, the level of radiocarbon in the tree’s outermost rings nearly doubled to almost two parts per trillion. But not long after the signing of the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963, that climb stopped. After a peak in 1964, each new ring of wood in Fay’s beech carried a little less radiocarbon. The fall was far slower than the climb. The level of radiocarbon in the last ring the beech grew before getting cut down was only 6 percent above the radiocarbon levels before Castle Bravo. Versions of the same sawtoothlike peak Gaylord drew had already been found in other parts of the world, including the rings of trees in New Zealand and the coral reefs of the Galapagos Islands. In October 2019, Gaylord unveiled an exquisitely clear version of the bomb spike in New England.

When scientists first discovered radiocarbon, in 1940, they did not find it in a tree or any other part of nature. They made it. Regular carbon has six protons and six neutrons. At UC Berkeley, Martin Kamen and Sam Ruben blasted carbon with a beam of neutrons and produced a new form, with eight neutrons instead of six. Unlike regular carbon, these new atoms turned out to be a source of radiation. Every second, a small portion of the carbon 14 atoms decayed into nitrogen, giving off radioactive particles. Kamen and Ruben used that rate of decay to estimate carbon 14’s half-life at 4,000 years. Later research would sharpen that estimate to 5,700 years.

Soon after Kamen and Ruben’s discovery, a University of Chicago physicist named Willard Libby determined that radiocarbon existed beyond the walls of Berkeley’s labs. Cosmic rays falling from space smashed into nitrogen atoms in the atmosphere every second of every day, transforming those atoms into carbon 14. And because plants and algae drew in carbon dioxide from the air, Libby realized, they should have radiocarbon in their tissue, as should the animals that eat those plants (and the animals that eat those animals, for that matter).

Libby reasoned that as long as an organism is alive and taking in carbon 14, the concentration of the isotope in its tissue should roughly match the concentration in the atmosphere. Once an organism dies, however, its radiocarbon should decay and eventually disappear completely.

To test this idea, Libby set out to measure carbon 14 in living organisms. He had colleagues go to a sewage-treatment plant in Baltimore, where they captured the methane given off by bacteria feeding on the sewage. When the methane samples arrived in Chicago, Libby extracted the carbon and put it in a radioactivity detector.. It crackled as carbon 14 decayed to nitrogen.

Read: Global warming could make carbon dating impossible

To see what happens to carbon 14 in dead tissue, Libby ran another experiment, this one with methane from oil wells. He knew that oil is made up of algae and other organisms that fell to the ocean floor and were buried for millions of years. Just as he had predicted, the methane from ancient oil contained no carbon 14 at all.

Libby then had another insight, one that would win him the Nobel Prize: The decay of carbon 14 in dead tissues acts like an archaeological clock. As the isotope decays inside a piece of wood, a bone, or some other form of organic matter, it can tell scientists how long ago that matter was alive. Radiocarbon dating, which works as far back as about 50,000 years, has revealed to us to when the Neanderthals became extinct, when farmers domesticated wheat, when the Dead Sea Scrolls were written. It has become the calendar of humanity.

Word of Libby’s breakthrough reached a New Zealand physicist named Athol Rafter. He began using radiocarbon dating on the bones of extinct flightless birds and ash from ancient eruptions. To make the clock more precise, Rafter measured the level of radiocarbon in the atmosphere. Every few weeks he climbed a hill outside the city of Wellington and set down a Pyrex tray filled with lye to trap carbon dioxide.

Rafter expected the level of radiocarbon to fluctuate. But he soon discovered that something else was happening: Month after month, the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was getting more radioactive. He dunked barrels into the ocean, and he found that the amount of carbon 14 was rising in seawater as well. He could even measure extra carbon 14 in the young leaves growing on trees in New Zealand.

The Castle Bravo test and the ones that followed had to be the source. They were turning the atmosphere upside down. Instead of cosmic rays falling from space, they were sending neutrons up to the sky, creating a huge new supply of radiocarbon.

In 1957, Rafter published his results in the journal Science. The implications were immediately clear—and astonishing: Man-made carbon 14 was spreading across the planet from test sites in the Pacific and the Arctic. It was even passing from the air into the oceans and trees.

Other scientists began looking, and they saw the same pattern. In Texas, the carbon 14 levels in new tree rings were increasing each year. In Holland, the flesh of snails gained more as well. In New York, scientists examined the lungs of a fresh human cadaver, and found that extra carbon 14 lurked in its cells. A living volunteer donated blood and an exhalation of air. Bomb radiocarbon was in those, too.

Bomb radiocarbon did not pose a significant threat to human health—certainly not compared with other elements released by bombs, such as plutonium and uranium. But its accumulation was deeply unsettling nonetheless. When Linus Pauling accepted the 1962 Nobel Peace Prize for his campaigning against hydrogen bombs, he said that carbon 14 “deserves our special concern” because it “shows the extent to which the earth is being changed by the tests of nuclear weapons.”

Photos: When we tested nuclear bombs

The following year, the signing of the Partial Test Ban Treaty stopped aboveground nuclear explosions, and ended the supply of bomb radiocarbon. All told, those tests produced about 60,000 trillion trillion new atoms of carbon 14. It would take cosmic rays 250 years to make that much. In 1964, Rafter quickly saw the treaty’s effect: His trays of lye had less carbon 14 than they had the year before.

Only a tiny fraction of the carbon 14 was decaying into nitrogen. For the most part, the atmosphere’s radiocarbon levels were dropping because the atoms were rushing out of the air. This exodus of radiocarbon gave scientists an unprecedented chance to observe how nature works.

Today scientists are still learning from these man-made atoms. “I feel a little bit bad about it,” says Kristie Boering, an atmospheric chemist at UC Berkeley who has studied radiocarbon for more than 20 years. “It’s a huge tragedy, the fact that we set off all these bombs to begin with. And then we get all this interesting scientific information from it for all these decades. It’s hard to know exactly how to pitch that when we’re giving talks. You can’t get too excited about the bombs that we set off, right?”

Yet the fact remains that for atmospheric scientists like Boering, bomb radiocarbon has lit up the sky like a tracer dye. When nuclear triggermen such as John Clark set off their bombs, most of the resulting carbon 14 shot up into the stratosphere directly above the impact sites. Each spring, parcels of stratospheric air gently fell down into the troposphere below, carrying with them a fresh load of carbon 14. It took a few months for these parcels to settle on weather stations on the ground. Only by following bomb radiocarbon did scientists discover this perpetual avalanche.

Once carbon 14 fell out of the stratosphere, it kept moving. The troposphere is made up of four great rings of circulating air. Inside each ring, warm air rises and flows through the sky away from the equator. Eventually it cools and sinks back to the ground, flowing toward the equator again before rising once more. At first, bomb radiocarbon remained trapped in the Northern Hemisphere rings, above where the tests had taken place. It took many years to leak through their invisible walls and move toward the tropics. After that, the annual monsoons sweeping through southern Asia pushed bomb radiocarbon over the equator and into the Southern Hemisphere.

The 60-Year Downfall of Nuclear Power in the U.S. Has Left a Huge Mess

America's Nuclear-Waste Plan Is a Giant Mess

What Lies Beneath

For most of the tree’s life, they found, the level had remained steady from one year to the next. But in 1954, John Clark initiated an extraordinary climb. The new supply of radiocarbon atoms in the atmosphere over Bikini Atoll spread around the world. When it reached Woods Hole, Fay’s beech tree absorbed the bomb radiocarbon in its summer leaves and added it to its new ring of wood.

As nuclear testing accelerated, Fay’s beech took on more radiocarbon. A graph pinned to the wall above the beech slab charts the changes. In less than a decade, the level of radiocarbon in the tree’s outermost rings nearly doubled to almost two parts per trillion. But not long after the signing of the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963, that climb stopped. After a peak in 1964, each new ring of wood in Fay’s beech carried a little less radiocarbon. The fall was far slower than the climb. The level of radiocarbon in the last ring the beech grew before getting cut down was only 6 percent above the radiocarbon levels before Castle Bravo. Versions of the same sawtoothlike peak Gaylord drew had already been found in other parts of the world, including the rings of trees in New Zealand and the coral reefs of the Galapagos Islands. In October 2019, Gaylord unveiled an exquisitely clear version of the bomb spike in New England.

When scientists first discovered radiocarbon, in 1940, they did not find it in a tree or any other part of nature. They made it. Regular carbon has six protons and six neutrons. At UC Berkeley, Martin Kamen and Sam Ruben blasted carbon with a beam of neutrons and produced a new form, with eight neutrons instead of six. Unlike regular carbon, these new atoms turned out to be a source of radiation. Every second, a small portion of the carbon 14 atoms decayed into nitrogen, giving off radioactive particles. Kamen and Ruben used that rate of decay to estimate carbon 14’s half-life at 4,000 years. Later research would sharpen that estimate to 5,700 years.

Soon after Kamen and Ruben’s discovery, a University of Chicago physicist named Willard Libby determined that radiocarbon existed beyond the walls of Berkeley’s labs. Cosmic rays falling from space smashed into nitrogen atoms in the atmosphere every second of every day, transforming those atoms into carbon 14. And because plants and algae drew in carbon dioxide from the air, Libby realized, they should have radiocarbon in their tissue, as should the animals that eat those plants (and the animals that eat those animals, for that matter).

Libby reasoned that as long as an organism is alive and taking in carbon 14, the concentration of the isotope in its tissue should roughly match the concentration in the atmosphere. Once an organism dies, however, its radiocarbon should decay and eventually disappear completely.

To test this idea, Libby set out to measure carbon 14 in living organisms. He had colleagues go to a sewage-treatment plant in Baltimore, where they captured the methane given off by bacteria feeding on the sewage. When the methane samples arrived in Chicago, Libby extracted the carbon and put it in a radioactivity detector.. It crackled as carbon 14 decayed to nitrogen.

Read: Global warming could make carbon dating impossible

To see what happens to carbon 14 in dead tissue, Libby ran another experiment, this one with methane from oil wells. He knew that oil is made up of algae and other organisms that fell to the ocean floor and were buried for millions of years. Just as he had predicted, the methane from ancient oil contained no carbon 14 at all.

Libby then had another insight, one that would win him the Nobel Prize: The decay of carbon 14 in dead tissues acts like an archaeological clock. As the isotope decays inside a piece of wood, a bone, or some other form of organic matter, it can tell scientists how long ago that matter was alive. Radiocarbon dating, which works as far back as about 50,000 years, has revealed to us to when the Neanderthals became extinct, when farmers domesticated wheat, when the Dead Sea Scrolls were written. It has become the calendar of humanity.

Word of Libby’s breakthrough reached a New Zealand physicist named Athol Rafter. He began using radiocarbon dating on the bones of extinct flightless birds and ash from ancient eruptions. To make the clock more precise, Rafter measured the level of radiocarbon in the atmosphere. Every few weeks he climbed a hill outside the city of Wellington and set down a Pyrex tray filled with lye to trap carbon dioxide.

Rafter expected the level of radiocarbon to fluctuate. But he soon discovered that something else was happening: Month after month, the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was getting more radioactive. He dunked barrels into the ocean, and he found that the amount of carbon 14 was rising in seawater as well. He could even measure extra carbon 14 in the young leaves growing on trees in New Zealand.

The Castle Bravo test and the ones that followed had to be the source. They were turning the atmosphere upside down. Instead of cosmic rays falling from space, they were sending neutrons up to the sky, creating a huge new supply of radiocarbon.

In 1957, Rafter published his results in the journal Science. The implications were immediately clear—and astonishing: Man-made carbon 14 was spreading across the planet from test sites in the Pacific and the Arctic. It was even passing from the air into the oceans and trees.

Other scientists began looking, and they saw the same pattern. In Texas, the carbon 14 levels in new tree rings were increasing each year. In Holland, the flesh of snails gained more as well. In New York, scientists examined the lungs of a fresh human cadaver, and found that extra carbon 14 lurked in its cells. A living volunteer donated blood and an exhalation of air. Bomb radiocarbon was in those, too.

Bomb radiocarbon did not pose a significant threat to human health—certainly not compared with other elements released by bombs, such as plutonium and uranium. But its accumulation was deeply unsettling nonetheless. When Linus Pauling accepted the 1962 Nobel Peace Prize for his campaigning against hydrogen bombs, he said that carbon 14 “deserves our special concern” because it “shows the extent to which the earth is being changed by the tests of nuclear weapons.”

Photos: When we tested nuclear bombs

The following year, the signing of the Partial Test Ban Treaty stopped aboveground nuclear explosions, and ended the supply of bomb radiocarbon. All told, those tests produced about 60,000 trillion trillion new atoms of carbon 14. It would take cosmic rays 250 years to make that much. In 1964, Rafter quickly saw the treaty’s effect: His trays of lye had less carbon 14 than they had the year before.

Only a tiny fraction of the carbon 14 was decaying into nitrogen. For the most part, the atmosphere’s radiocarbon levels were dropping because the atoms were rushing out of the air. This exodus of radiocarbon gave scientists an unprecedented chance to observe how nature works.

Today scientists are still learning from these man-made atoms. “I feel a little bit bad about it,” says Kristie Boering, an atmospheric chemist at UC Berkeley who has studied radiocarbon for more than 20 years. “It’s a huge tragedy, the fact that we set off all these bombs to begin with. And then we get all this interesting scientific information from it for all these decades. It’s hard to know exactly how to pitch that when we’re giving talks. You can’t get too excited about the bombs that we set off, right?”

Yet the fact remains that for atmospheric scientists like Boering, bomb radiocarbon has lit up the sky like a tracer dye. When nuclear triggermen such as John Clark set off their bombs, most of the resulting carbon 14 shot up into the stratosphere directly above the impact sites. Each spring, parcels of stratospheric air gently fell down into the troposphere below, carrying with them a fresh load of carbon 14. It took a few months for these parcels to settle on weather stations on the ground. Only by following bomb radiocarbon did scientists discover this perpetual avalanche.

Once carbon 14 fell out of the stratosphere, it kept moving. The troposphere is made up of four great rings of circulating air. Inside each ring, warm air rises and flows through the sky away from the equator. Eventually it cools and sinks back to the ground, flowing toward the equator again before rising once more. At first, bomb radiocarbon remained trapped in the Northern Hemisphere rings, above where the tests had taken place. It took many years to leak through their invisible walls and move toward the tropics. After that, the annual monsoons sweeping through southern Asia pushed bomb radiocarbon over the equator and into the Southern Hemisphere.

Zoe van Djik

Eventually, some of the bomb radiocarbon fell all the way to the surface of the planet. Some of it was absorbed by trees and other plants, which then died and delivered some of that radiocarbon to the soil. Other radiocarbon atoms settled into the ocean, to be carried along by its currents.

Carbon 14 “is inextricably linked to our understanding of how the water moves,” says Steve Beaupre, an oceanographer at Stony Brook University, in New York.

In the 1970s, marine scientists began carrying out the first major chemical surveys of the world’s oceans. They found that bomb radiocarbon had penetrated the top 1,000 meters of the ocean. Deeper than that, it became scarce. This pattern helped oceanographers figure out that the ocean, like the atmosphere above, is made up of layers of water that remain largely separate.

The warm, relatively fresh water on the surface of the ocean glides over the cold, salty depths. These surface currents become saltier as they evaporate, and eventually, at a few crucial spots on the planet, these streams get so dense that they fall to the bottom of the ocean. The bomb radiocarbon from Castle Bravo didn’t start plunging down into the depths of the North Atlantic until the 1980s, when John Clark was two decades into retirement. It’s still down there, where it will be carried along the seafloor by bottom-hugging ocean currents for hundreds of years before it rises to the light of day.

Some of the bomb radiocarbon that falls into the ocean makes its way into ocean life, too. Some corals grow by adding rings of calcium carbonate, and they have recorded their own version of the bomb spike. Their spike lagged well behind the one that Rafter recorded, thanks to the extra time the radiocarbon took to mix into the ocean. Algae and microbes on the surface of the ocean also take up carbon from the air, and they feed a huge food web in turn. The living things in the upper reaches of the ocean release organic carbon that falls gently to the seafloor—a jumble of protoplasmic goo, dolphin droppings, starfish eggs, and all manner of detritus that scientists call marine snow. In recent decades, that marine snow has become more radioactive.

In 2009, a team of Chinese researchers sailed across the Pacific and dropped traps 36,000 feet down to the bottom of the Mariana Trench. When they hauled the traps up, there were minnow-size, shrimplike creatures inside. These were Hirondellea gigas, a deep-sea invertebrate that forages on the seafloor for bits of organic carbon. The animals were flush with bomb radiocarbon—a puzzling discovery, because the organic carbon that sits on the floor of the Mariana Trench is thousands of years old. It was as if they had been dining at the surface of the ocean, not at its greatest depths. In a few of the Hirondellea, the researchers found undigested particles of organic carbon. These meals were also high in carbon 14.

Eventually, some of the bomb radiocarbon fell all the way to the surface of the planet. Some of it was absorbed by trees and other plants, which then died and delivered some of that radiocarbon to the soil. Other radiocarbon atoms settled into the ocean, to be carried along by its currents.

Carbon 14 “is inextricably linked to our understanding of how the water moves,” says Steve Beaupre, an oceanographer at Stony Brook University, in New York.

In the 1970s, marine scientists began carrying out the first major chemical surveys of the world’s oceans. They found that bomb radiocarbon had penetrated the top 1,000 meters of the ocean. Deeper than that, it became scarce. This pattern helped oceanographers figure out that the ocean, like the atmosphere above, is made up of layers of water that remain largely separate.

The warm, relatively fresh water on the surface of the ocean glides over the cold, salty depths. These surface currents become saltier as they evaporate, and eventually, at a few crucial spots on the planet, these streams get so dense that they fall to the bottom of the ocean. The bomb radiocarbon from Castle Bravo didn’t start plunging down into the depths of the North Atlantic until the 1980s, when John Clark was two decades into retirement. It’s still down there, where it will be carried along the seafloor by bottom-hugging ocean currents for hundreds of years before it rises to the light of day.

Some of the bomb radiocarbon that falls into the ocean makes its way into ocean life, too. Some corals grow by adding rings of calcium carbonate, and they have recorded their own version of the bomb spike. Their spike lagged well behind the one that Rafter recorded, thanks to the extra time the radiocarbon took to mix into the ocean. Algae and microbes on the surface of the ocean also take up carbon from the air, and they feed a huge food web in turn. The living things in the upper reaches of the ocean release organic carbon that falls gently to the seafloor—a jumble of protoplasmic goo, dolphin droppings, starfish eggs, and all manner of detritus that scientists call marine snow. In recent decades, that marine snow has become more radioactive.

In 2009, a team of Chinese researchers sailed across the Pacific and dropped traps 36,000 feet down to the bottom of the Mariana Trench. When they hauled the traps up, there were minnow-size, shrimplike creatures inside. These were Hirondellea gigas, a deep-sea invertebrate that forages on the seafloor for bits of organic carbon. The animals were flush with bomb radiocarbon—a puzzling discovery, because the organic carbon that sits on the floor of the Mariana Trench is thousands of years old. It was as if they had been dining at the surface of the ocean, not at its greatest depths. In a few of the Hirondellea, the researchers found undigested particles of organic carbon. These meals were also high in carbon 14.

Read: A troubling discovery in the deepest ocean trenches

The bomb radiocarbon could not have gotten there by riding the ocean’s conveyor belt, says Ellen Druffel, a scientist at UC Irvine who collaborated with the Chinese team. “The only way you can get bomb carbon by circulation down to the deep Pacific would take 500 years,” she says. Instead, Hirondellea must be dining on freshly fallen marine snow.

“I must admit, when I saw the data it was really amazing,” Dreffel says. “These organisms were sifting out the very youngest material from the surface ocean. They were just leaving behind everything else that came down.”

More than 60 years have passed since the peak of the bomb spike, and yet bomb radiocarbon is telling us new stories about the world. That’s because experts like Mary Gaylord are getting better at gathering these rare atoms. At Woods Hole, Gaylord works at the National Ocean Sciences Accelerator Mass Spectrometry facility (NOSAMS for short). She prepares samples for analysis in a thicket of pipes, wires, glass tubes, and jars of frothing liquid nitrogen. “Our whole life is vacuum lines and vacuum pumps,” she told me.

At NOSAMS, Gaylord and her colleagues measure radiocarbon in all manner of things: sea spray, bat guano, typhoon-tossed trees. The day I visited, Gaylord was busy with fish eyes. Black-capped vials sat on a lab bench, each containing a bit of lens from a red snapper.

The wispy, pale tissue had come to NOSAMS from Florida. A biologist named Beverly Barnett had gotten hold of eyes from red snapper caught in the Gulf of Mexico and sliced out their lenses. Barnett then peeled away the layers of the lenses one at a time. When she describes this work, she makes it sound like woodworking or needlepoint—a hobby anyone would enjoy. “It’s like peeling off the layers of an onion,” she told me. “It’s really nifty to see.”

Eventually, Barnett made her way down to the tiny nub at the center of each lens. These bits of tissue developed when the red snapper were still in their eggs. And Barnett wanted to know exactly how much bomb radiocarbon is in these precious fragments. In a couple of days, Gaylord and her colleagues would be able to tell her.

Gaylord started by putting the lens pieces into an oven that slowly burned them away. The vapors and smoke flowed into a pipe, chased by helium and nitrogen. Gaylord separated the carbon dioxide from the other compounds, and then shunted it into chilled glass tubes. There it formed a frozen fog on the inside walls.

Later, the team at NOSAMS would transform the frozen carbon dioxide into chips of graphite, which they would then load into what looks like an enormous, crooked laser cannon. At one end of the cannon, graphite gets vaporized, and the liberated carbon atoms fly down the barrel. By controlling the magnetic field and other conditions inside the cannon, the researchers cause the carbon 14 atoms to veer away from the carbon 12 atoms and other elements. The carbon 14 atoms fly onward on their own until they strike a sensor.

Ultimately, all of this effort will end up in a number: the number of carbon 14 atoms in the red-snapper lens. For Barnett, every one of those atoms counts. They can tell her the exact age of the red snapper when the fish were caught.

That’s because lenses are peculiar organs. Most of our cells keep making new proteins and destroying old ones. Cells in the lens, however, fill up with light-bending proteins and then die, their proteins locked in place for the rest of our life. The layers of cells at the core of the red-snapper lenses have the same carbon 14 levels that they did when the fish were in their eggs.

Using lenses to estimate the ages of animals is still a new undertaking. But it’s already delivered some surprises. In 2016, for example, a team of Danish researchers studied the lenses from Greenland sharks ranging in size from two and a half to 16 feet long. The lenses of the sharks up to seven feet long had high levels of radiocarbon in them. That meant the sharks had hatched no earlier than the 1960s. The bigger sharks all had much lower levels of radiocarbon in their lenses—meaning that they had been born before Castle Bravo. By extrapolating out from these results, the researchers estimated that Greenland sharks have a staggeringly long life span, reaching up to 390 years or perhaps even more.

Barnett has been developing an even more precise clock for her red snapper, taking advantage of the fact that the level of bomb radiocarbon peaked in the Gulf of Mexico in the 1970s and has been falling ever since. By measuring the level of bomb radiocarbon in the center of the snapper lenses, she can determine the year when the fish hatched.

Knowing the age of fish with this kind of precision is powerful. Fishery managers can track the ages of the fish that are caught each year, information that they can then use to make sure their stocks don’t collapse. Barnett wants to study fish in the Gulf of Mexico to see how they were affected by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill of 2010. Their eyes can tell her how old they were when they were hit by that disaster.

When it comes to carbon, we are no different than red snapper or Greenland sharks. We use the carbon in the food we eat to build our body, and the level of bomb radiocarbon inside of us reflects our age. People born in the early 1960s have more radiocarbon in their lenses than people born before that time. People born in the years since then have progressively less.

For forensic scientists who need to determine the age of skeletal remains, lenses aren’t much help. But teeth are. As children develop teeth, they incorporate carbon into the enamel. If people’s teeth have a very low level of radiocarbon, it means that they were born well before Castle Bravo. People born in the early 1960s have high levels of radiocarbon in their molars, which develop early, and lower levels in their wisdom teeth, which grow years later. By matching each tooth in a jaw to the bomb curve, forensic scientists can estimate the age of a skeleton to within one or two years.

Even after childhood, bomb radiocarbon chronicles the history of our body. When we build new cells, we make DNA strands out of the carbon in our food. Scientists have used bomb radiocarbon in people’s DNA to determine the age of their cells. In our brains, most of the cells form around the time we’re born. But many cells in our hearts and other organs are much younger.

We also build other molecules throughout our lives, including fat. In a September 2019 study, Kirsty Spalding of the Karolinska Institute, near Stockholm, used bomb radiocarbon to study why people put on weight. Researchers had long known that our level of fat is the result of how much new fat we add to our body relative to how much we burn. But they didn’t have direct evidence for exactly how that balance influences our weight over the course of our life.

Spalding and her colleagues found 54 people from whom doctors had taken fat biopsies and asked if they could follow up. The fat samples spanned up to 16 years. By measuring the age of the fat in each sample, the researchers could estimate the rate at which each person added and removed fat over their lives.

The reason we put on weight as we get older, the researchers concluded, is that we get worse at removing fat from our bodies. “Before, you could intuitively believe that the rate at which we burn fat decreases as we age,” Spalding says, “but we showed it for the first time scientifically.”

Unexpectedly, though, Spalding discovered that the people who lost weight and kept it off successfully were the ones who burned their fat slowly. “I was quite surprised by that data,” Spalding said. “It adds new and interesting biology to understanding how to help people maintain weight loss.”

Children who are just now going through teething pains will have only a little more bomb radiocarbon in their enamel than children born before Castle Bravo did. Over the past six decades, the land and ocean have removed much of what nuclear bombs put into the air. Heather Graven, a climate scientist at Imperial College London, is studying this decline. It helps her predict the future of the planet.

Graven and her colleagues build models of the world to study the climate. As we emit fossil fuels, the extra carbon dioxide traps heat. How much heat we’re facing in centuries to come depends in part on how much carbon dioxide the oceans and land can remove. Graven can use the rise and fall of bomb radiocarbon as a benchmark to test her models.

In a recent study, she and her colleagues unleashed a virtual burst of nuclear-weapons tests. Then they tracked the fate of her simulated bomb radiocarbon to the present day. Much to Graven’s relief, the radiocarbon in the atmosphere quickly rose and then gradually fell. The bomb spike in her virtual world looks much like the one recorded in Joseph Fay’s beech tree.

Graven can keep running her simulation beyond what Fay’s beech and other records tell us about the past. According to her model, the level of radiocarbon in the atmosphere should drop in 2020 to the level before Castle Bravo.

“It’s right around now that we’re crossing over,” Graven told me.

Graven will have to wait for scientists to analyze global measurements of radiocarbon in the air to see whether she’s right. That’s important to find out, because Graven’s model suggests that the bomb spike is falling faster than the oceans and land alone can account for. When the ocean and land draw down bomb radiocarbon, they also release some of it back into the air. That two-way movement of bomb radiocarbon ought to cause its concentration in the atmosphere to level off a little above the pre–Castle Bravo mark. Instead, Graven’s model suggests, it continues to fall. She suspects that the missing factor is us.

We mine coal, drill for oil and gas, and then burn all that fossil fuel to power our cars, cool our houses, power our factories. In 1954, the year that John Clark set off Castle Bravo, humans emitted 6 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the air. In 2018, humans emitted about 37 billion tons. As Willard Libby first discovered, this fossil fuel has no radiocarbon left. By burning it, we are lowering the level of radiocarbon in the atmosphere, like a bartender watering down the top-shelf liquor.

If we keep burning fossil fuels at our accelerating rate, the planet will veer into climate chaos. And once more, radiocarbon will serve as a witness to our self-destructive actions. Unless we swiftly stop burning fossil fuels, we will push carbon 14 down far below the level it was at before the nuclear bombs began exploding.

To Graven, the coming radiocarbon crash is just as significant as the bomb spike has been. “We're transitioning from a bomb signal to a fossil-fuel-dilution signal,” she said.

The author Jonathan Weiner once observed that we should think of burning fossil fuels as a disturbance on par with nuclear-weapon detonations. “It is a slow-motion explosion manufactured by every last man, woman and child on the planet,” he wrote. If we threw up our billions of tons of carbon into the air all at once, it would dwarf Castle Bravo. “A pillar of fire would seem to extend higher into the sky and farther into the future than the eye can see,” Weiner wrote.

Bomb radiocarbon showed us how nuclear weapons threatened the entire world. Today, everyone on Earth still carries that mark. Now our pulse of carbon 14 is turning into an inverted bomb spike, a new signal of the next great threat to human survival.

Spalding and her colleagues found 54 people from whom doctors had taken fat biopsies and asked if they could follow up. The fat samples spanned up to 16 years. By measuring the age of the fat in each sample, the researchers could estimate the rate at which each person added and removed fat over their lives.

The reason we put on weight as we get older, the researchers concluded, is that we get worse at removing fat from our bodies. “Before, you could intuitively believe that the rate at which we burn fat decreases as we age,” Spalding says, “but we showed it for the first time scientifically.”

Unexpectedly, though, Spalding discovered that the people who lost weight and kept it off successfully were the ones who burned their fat slowly. “I was quite surprised by that data,” Spalding said. “It adds new and interesting biology to understanding how to help people maintain weight loss.”

Children who are just now going through teething pains will have only a little more bomb radiocarbon in their enamel than children born before Castle Bravo did. Over the past six decades, the land and ocean have removed much of what nuclear bombs put into the air. Heather Graven, a climate scientist at Imperial College London, is studying this decline. It helps her predict the future of the planet.

Graven and her colleagues build models of the world to study the climate. As we emit fossil fuels, the extra carbon dioxide traps heat. How much heat we’re facing in centuries to come depends in part on how much carbon dioxide the oceans and land can remove. Graven can use the rise and fall of bomb radiocarbon as a benchmark to test her models.

In a recent study, she and her colleagues unleashed a virtual burst of nuclear-weapons tests. Then they tracked the fate of her simulated bomb radiocarbon to the present day. Much to Graven’s relief, the radiocarbon in the atmosphere quickly rose and then gradually fell. The bomb spike in her virtual world looks much like the one recorded in Joseph Fay’s beech tree.

Graven can keep running her simulation beyond what Fay’s beech and other records tell us about the past. According to her model, the level of radiocarbon in the atmosphere should drop in 2020 to the level before Castle Bravo.

“It’s right around now that we’re crossing over,” Graven told me.

Graven will have to wait for scientists to analyze global measurements of radiocarbon in the air to see whether she’s right. That’s important to find out, because Graven’s model suggests that the bomb spike is falling faster than the oceans and land alone can account for. When the ocean and land draw down bomb radiocarbon, they also release some of it back into the air. That two-way movement of bomb radiocarbon ought to cause its concentration in the atmosphere to level off a little above the pre–Castle Bravo mark. Instead, Graven’s model suggests, it continues to fall. She suspects that the missing factor is us.

We mine coal, drill for oil and gas, and then burn all that fossil fuel to power our cars, cool our houses, power our factories. In 1954, the year that John Clark set off Castle Bravo, humans emitted 6 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the air. In 2018, humans emitted about 37 billion tons. As Willard Libby first discovered, this fossil fuel has no radiocarbon left. By burning it, we are lowering the level of radiocarbon in the atmosphere, like a bartender watering down the top-shelf liquor.

If we keep burning fossil fuels at our accelerating rate, the planet will veer into climate chaos. And once more, radiocarbon will serve as a witness to our self-destructive actions. Unless we swiftly stop burning fossil fuels, we will push carbon 14 down far below the level it was at before the nuclear bombs began exploding.

To Graven, the coming radiocarbon crash is just as significant as the bomb spike has been. “We're transitioning from a bomb signal to a fossil-fuel-dilution signal,” she said.

The author Jonathan Weiner once observed that we should think of burning fossil fuels as a disturbance on par with nuclear-weapon detonations. “It is a slow-motion explosion manufactured by every last man, woman and child on the planet,” he wrote. If we threw up our billions of tons of carbon into the air all at once, it would dwarf Castle Bravo. “A pillar of fire would seem to extend higher into the sky and farther into the future than the eye can see,” Weiner wrote.

Bomb radiocarbon showed us how nuclear weapons threatened the entire world. Today, everyone on Earth still carries that mark. Now our pulse of carbon 14 is turning into an inverted bomb spike, a new signal of the next great threat to human survival.

CARL ZIMMER is a columnist at The New York Times. His latest book is She Has Her Mother’s Laugh: The Powers, Perversions, and Potential of Heredity.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8557761/Palantiri.jpg) '

'