THALIDOMIDE

Jerry Adler Senior Editor,Yahoo News•May 16, 2020

Along with everyone else in the world, President Trump wants a coronavirus vaccine now.

Or, if not now, then “prior to the end of the year,” as he said at the White House on Friday, which Moncef Slaoui, the drug company executive the president tapped to head the effort, called a “very credible” timetable. By historical standards, it is an extraordinarily ambitious goal. Some vaccines have taken a decade or longer to develop, test and manufacture. The most optimistic time by which a coronavirus vaccine might be ready, according to Dr. Anthony Fauci, the leading infectious disease specialist on the president’s coronavirus task force, is 12 to 18 months.

Underscoring his sense of urgency, Trump has compared the vaccine effort to the Manhattan Project to develop an atom bomb during World War II, and dubbed it “Operation Warp Speed.”

President Trump speaks in the Rose Garden on Friday. (Stefani Reynolds/CNP/Bloomberg via Getty images)

President Trump speaks in the Rose Garden on Friday. (Stefani Reynolds/CNP/Bloomberg via Getty images)Warp speed is an invented term for travel faster than light, which is possible only in the fictional universe of “Star Trek.” Whether it will work for the creating a vaccine for a lethal disease remains to be seen. But there are a few hundred, possibly thousands, of people now in their 60s who are living reminders of the unintended consequences of putting a drug into people’s bodies without adequate testing.

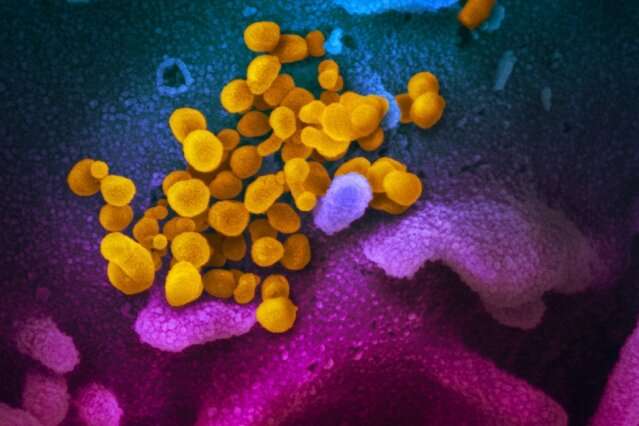

Genetic engineering greatly speeds the process of developing a vaccine. But public health experts are still sorting through how to test it for safety and efficacy. The primary measure of safety, of course, is that a new vaccine doesn’t make people sick, which is easy enough to verify, although it would need to be tried in a large and diverse population to catch possibly rare side effects.

Efficacy is more complicated: Researchers can detect if people inoculated with the vaccine produce antibodies to the coronavirus, but how do they know if they are actually immune from future infection. One way, obviously, is to just watch them and see if they get sick (technically, if they get sick less often, or less severely, than an unvaccinated control group). But that’s a slow process. The other way, which is gaining support among researchers, is a “challenge trial,” in which volunteers receive an inoculation and then are exposed to an infectious dose of the virus — which clearly poses risks of its own. Challenge trials are usually done for diseases that are not as lethal as the coronavirus, or for which other therapies exist.

Quoted in The Hill, Jeffrey Kahn, director of the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics, said he did not see how an institutional review board that oversees research would approve a human challenge trial for the coronavirus.

Children born with malformed limbs getting used to using prostheses, July 1962.(Stan Wayman/The Life Picture Collection via Getty Images)

But Operation Warp Speed is proceeding along numerous tracks simultaneously: the genetic engineering of potential vaccines, testing in animals, trials in humans, and ramping up the production of the syringes, vials and other equipment necessary for mass inoculation. On Friday, Trump said “we’re gearing up” to begin manufacturing vaccines even before one (or more) is approved, so that there will be a stock on hand in advance. “That means they’d better come up with a good vaccine,” he said. “It’s risky, it’s expensive,” but it could cut a year off the time that might otherwise be required to put a vaccine into distribution.

Vaccines, of course, are suspect to a dismayingly large segment of the population, but for other reasons. Many Americans believe that they cause autism in children, an assertion that has been investigated and declared spurious by virtually the entire medical profession. That’s not what this is about.

Trump has boasted frequently about his success in speeding up the approval process for drugs, a move long urged by pharmaceutical companies, which regard it as a costly obstacle to getting their products to market. And in the coronavirus emergency, epidemiologists and bioethics experts generally are going along with steps that could make a vaccine available sooner.

After all, what could go wrong?

The FDA’s website itself holds a possible answer, in the form of a tribute to a now-forgotten hero of bureaucracy, a physician and pharmacologist named Frances Kelsey. In 1960, she joined the FDA, where her job was to review applications for drug approval.

The first application she handled was for a sedative called thalidomide, which was used in the treatment of leprosy and was being marketed to prevent “morning sickness,” the nausea and vomiting that affects some women during pregnancy. The drug company presented data that it said proved its safety. It was already being sold over the counter in other countries.

Kelsey was unconvinced and asked for more data. The company sent in more studies, but she was adamant. Among other red flags, the manufacturer hadn’t proven that thalidomide was safe when taken by pregnant women. This was, of course, a period in American history when government regulations were more commonly referred to as “life-saving” than “job-killing,” and the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations appear not to have interjected themselves into the debate.

But Operation Warp Speed is proceeding along numerous tracks simultaneously: the genetic engineering of potential vaccines, testing in animals, trials in humans, and ramping up the production of the syringes, vials and other equipment necessary for mass inoculation. On Friday, Trump said “we’re gearing up” to begin manufacturing vaccines even before one (or more) is approved, so that there will be a stock on hand in advance. “That means they’d better come up with a good vaccine,” he said. “It’s risky, it’s expensive,” but it could cut a year off the time that might otherwise be required to put a vaccine into distribution.

Vaccines, of course, are suspect to a dismayingly large segment of the population, but for other reasons. Many Americans believe that they cause autism in children, an assertion that has been investigated and declared spurious by virtually the entire medical profession. That’s not what this is about.

Trump has boasted frequently about his success in speeding up the approval process for drugs, a move long urged by pharmaceutical companies, which regard it as a costly obstacle to getting their products to market. And in the coronavirus emergency, epidemiologists and bioethics experts generally are going along with steps that could make a vaccine available sooner.

After all, what could go wrong?

The FDA’s website itself holds a possible answer, in the form of a tribute to a now-forgotten hero of bureaucracy, a physician and pharmacologist named Frances Kelsey. In 1960, she joined the FDA, where her job was to review applications for drug approval.

The first application she handled was for a sedative called thalidomide, which was used in the treatment of leprosy and was being marketed to prevent “morning sickness,” the nausea and vomiting that affects some women during pregnancy. The drug company presented data that it said proved its safety. It was already being sold over the counter in other countries.

Kelsey was unconvinced and asked for more data. The company sent in more studies, but she was adamant. Among other red flags, the manufacturer hadn’t proven that thalidomide was safe when taken by pregnant women. This was, of course, a period in American history when government regulations were more commonly referred to as “life-saving” than “job-killing,” and the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations appear not to have interjected themselves into the debate.

President John F. Kennedy stands with Dr. Frances Kelsey, the medical officer who prevented the sale of the birth defect-causing drug thalidomide in the United States. (Bettmann Archive via Getty images)

A year later, with FDA approval still pending, reports began to circulate of a peculiar, and devastating, syndrome of birth defects among the children of mothers who had taken thalidomide early in their pregnancies. The children, some of whom were miscarried or stillborn, had damage to various organs and, famously, malformed, missing or greatly shortened limbs, in the most severe cases with hands and feet that grew directly out of their torso. Some 10,000 babies were born that way in Germany, Britain and other countries. There were a few dozen cases in the United States, believed to have resulted from a loosely supervised trial, but nothing like the thousands that might otherwise have resulted.

Kelsey later was honored by President John F. Kennedy with the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service. Thalidomide was eventually approved, under restrictions, for use in treating some cancers. The episode led to the Kefauver Harris Amendment to the Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act, which was adopted in 1962 and greatly tightened regulation of the pharmaceutical industry.

Of course, while COVID-19 is a lethal and highly contagious disease, morning sickness, though unpleasant and sometimes debilitating, is not fatal and goes away by itself. So the standards for approving a vaccine or treatment for the coronavirus should be set with that in mind.

Still, it would be nice if Kelsey, who died in 2015, at age 101, was around to take a look at the paperwork. One can hope her successors will do as good a job.

A year later, with FDA approval still pending, reports began to circulate of a peculiar, and devastating, syndrome of birth defects among the children of mothers who had taken thalidomide early in their pregnancies. The children, some of whom were miscarried or stillborn, had damage to various organs and, famously, malformed, missing or greatly shortened limbs, in the most severe cases with hands and feet that grew directly out of their torso. Some 10,000 babies were born that way in Germany, Britain and other countries. There were a few dozen cases in the United States, believed to have resulted from a loosely supervised trial, but nothing like the thousands that might otherwise have resulted.

Kelsey later was honored by President John F. Kennedy with the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service. Thalidomide was eventually approved, under restrictions, for use in treating some cancers. The episode led to the Kefauver Harris Amendment to the Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act, which was adopted in 1962 and greatly tightened regulation of the pharmaceutical industry.

Of course, while COVID-19 is a lethal and highly contagious disease, morning sickness, though unpleasant and sometimes debilitating, is not fatal and goes away by itself. So the standards for approving a vaccine or treatment for the coronavirus should be set with that in mind.

Still, it would be nice if Kelsey, who died in 2015, at age 101, was around to take a look at the paperwork. One can hope her successors will do as good a job.

PS CANADA IGNORED HER ADVICE AND DID NOT FOLLOW THE AMERICANS RESULTING IN MANY MORE THALIDOMIDE BABIES IN CANADA THAN IN THE USA

PER POP SIZE