55 years ago, a cardinal’s ‘special reverence’ for the Jews redeemed ‘Nostra Aetate’

The proclamation sparked a systematic effort by the Catholic Church to transform its past bitter relationships with Jews and Judaism.

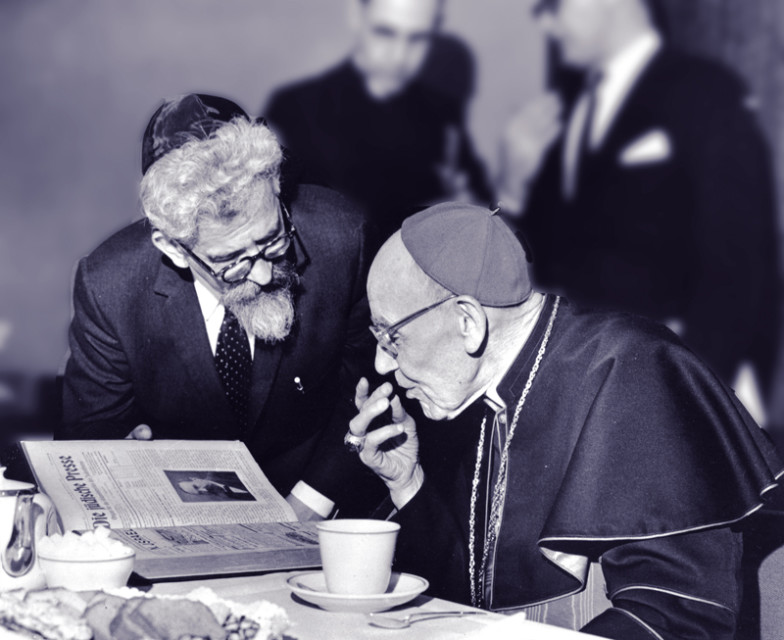

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel meeting in New York with Cardinal Augustin Bea, who shepherded the process of Catholic introspection that led to "Nostra Aetate," on March 31, 1963. Photo courtesy of American Jewish Committee

The proclamation sparked a systematic effort by the Catholic Church to transform its past bitter relationships with Jews and Judaism.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel meeting in New York with Cardinal Augustin Bea, who shepherded the process of Catholic introspection that led to "Nostra Aetate," on March 31, 1963. Photo courtesy of American Jewish Committee

October 28, 2020

By A. James Rudin

(RNS) — Fifty-five years ago, on Oct. 28, 1965, an extraordinary global religious “game changer” took place in Rome.

At the conclusion of the Second Vatican Council, after three years of intense deliberation and debate, the world’s Roman Catholic bishops voted overwhelmingly that day to adopt the historic declaration titled “Nostra Aetate (In Our Time).”

The proclamation, promulgated by Pope Paul VI, set in motion a revolution of the human spirit and sparked a serious and systematic effort by the Catholic Church as well as other Christian bodies around the world to transform their past bitter relationships with Jews and Judaism.

The English translation of the original Latin text, only 624 words in length, rejected the ancient lethal and odious charge that the Jews were “Christ killers.” (It was the Roman occupiers of the land of Judea who executed Jesus.)

The specific term “anti-Semitism” (hatred of Jews and Judaism) appears in “Nostra Aetate”: The church, it reads, “ … decries hatred, persecution, (and) displays of anti-Semitism directed against Jews at any time and by anyone.”

The declaration also specifically called for “mutual understanding and respect” and the establishment of “biblical and theological studies” as well as “fraternal dialogues” between Catholics and Jews.

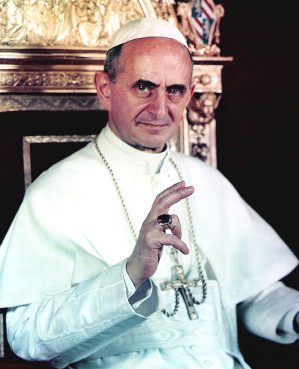

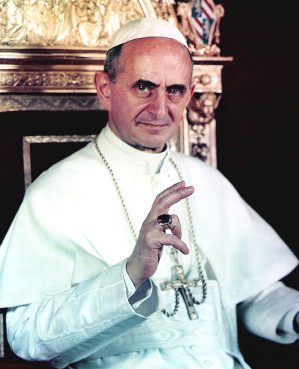

Pope Paul VI in 1963. Vatican City official photo/Creative Commons

In 1965, it was understood that future generations of Catholics and Jews would be required to give life and meaning to the tightly worded declaration, but a solid, hard-won foundation had been laid. In fact, the past 55 years have seen more positive relations between Roman Catholics and Jews than in the first 1,900-plus years of the church’s existence.

While the vote in 1965 was overwhelming, a year earlier it seemed clear to many observers that any constructive groundbreaking statement on Catholic-Jewish relations was doomed. Various versions of such a document had stalled in the Vatican Council’s drafting committee, despite the strong support of Popes John XXIII and Paul VI for systemic changes within the world’s largest Christian community.

The strategy of bishops who opposed any positive statement about Jews and Judaism was to “table it for further study”: a well-known bureaucratic prescription for a certain death.

Faced with that dire possibility, just 20 years after the murderous Holocaust in the heart of what Pope John Paul II called “Christian Europe,” many American Catholic leaders became alarmed. Cardinal Richard James Cushing, then archbishop of Boston, was fearful no action would be taken on the critical issues of deicide and anti-Semitism. He felt an urgent need to express his concerns in person in Rome.

Cushing led the forces not only of the United States but of all Catholics, recruiting similar positive views from other parts of the globe. He especially wanted to speak personally to his brother bishops assembled in Rome during the Vatican Council.

His focus was on the need for his beloved church to rid itself of anti-Semitism, a terrible prejudice that defamed Jews and debilitated Roman Catholics everywhere. Cushing, who always hated leaving his beloved Boston, nonetheless traveled to Rome and delivered the greatest speech of his life on Sept. 28, 1964.

The cardinal’s remarks, given in St. Peter’s Basilica, were delivered in Latin with Cushing’s raspy, heavy New England accent. It drew wide attention and exhilarated many of his fellow bishops. One observer recalled that the Bostonian’s strong voice overwhelmed the microphones and echoed throughout the basilica.

Cardinal Richard Cushing in the 1960s. Copyright City of Boston

When he finished speaking, his rapt audience applauded Cushing. I strongly believe his powerful heartfelt words saved “Nostra Aetate” from oblivion.

In a time of increased acts of anti-Semitism in the United States, Europe and other parts of the world, Cushing’s words resonate today, more than a half-century later: “ … How many (Jews) have suffered in our own time? How many died because Christians were indifferent or kept silent? If in recent years, not many Christian voices were raised against those injustices, at least let ours now be heard in humility.”

We must, he continued, “foster a special reverence and love for the children of Abraham. … (Jews) are Christ’s blood relatives. … (We cannot) burden … generations of Jews with any burden of guilt for the crucifixion of the Lord Jesus. … In clear and unmistakable language, we must deny that the Jews are guilty of our Savior’s death.”

He concluded, “In this august assembly, in this solemn moment, we must cry out: There is no Christian rationale — neither theological nor historical — for any iniquity, hatred or persecution of our Jewish brothers. … Great is the hope … that this sacred synod will make such a fitting declaration … ”

His speech was widely reported and his portrait appeared on the cover of Time magazine, a recognition at the time of his personal leadership.

Thanks in great part to the efforts of Cushing and other American Catholic leaders, exactly 13 months after Cushing’s speech, the Vatican Council did, in fact, ” … make a fitting declaration” that would not have happened without the Boston cardinal’s leadership.

(Rabbi A. James Rudin is the American Jewish Committee’s senior interreligious adviser and the author of “Cushing, Spellman, O’Connor: The Surprising Story of How Three American Cardinals Transformed Catholic-Jewish Relations.” He can be reached at jamesrudin.com. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

By A. James Rudin

(RNS) — Fifty-five years ago, on Oct. 28, 1965, an extraordinary global religious “game changer” took place in Rome.

At the conclusion of the Second Vatican Council, after three years of intense deliberation and debate, the world’s Roman Catholic bishops voted overwhelmingly that day to adopt the historic declaration titled “Nostra Aetate (In Our Time).”

The proclamation, promulgated by Pope Paul VI, set in motion a revolution of the human spirit and sparked a serious and systematic effort by the Catholic Church as well as other Christian bodies around the world to transform their past bitter relationships with Jews and Judaism.

The English translation of the original Latin text, only 624 words in length, rejected the ancient lethal and odious charge that the Jews were “Christ killers.” (It was the Roman occupiers of the land of Judea who executed Jesus.)

The specific term “anti-Semitism” (hatred of Jews and Judaism) appears in “Nostra Aetate”: The church, it reads, “ … decries hatred, persecution, (and) displays of anti-Semitism directed against Jews at any time and by anyone.”

The declaration also specifically called for “mutual understanding and respect” and the establishment of “biblical and theological studies” as well as “fraternal dialogues” between Catholics and Jews.

Pope Paul VI in 1963. Vatican City official photo/Creative Commons

In 1965, it was understood that future generations of Catholics and Jews would be required to give life and meaning to the tightly worded declaration, but a solid, hard-won foundation had been laid. In fact, the past 55 years have seen more positive relations between Roman Catholics and Jews than in the first 1,900-plus years of the church’s existence.

While the vote in 1965 was overwhelming, a year earlier it seemed clear to many observers that any constructive groundbreaking statement on Catholic-Jewish relations was doomed. Various versions of such a document had stalled in the Vatican Council’s drafting committee, despite the strong support of Popes John XXIII and Paul VI for systemic changes within the world’s largest Christian community.

The strategy of bishops who opposed any positive statement about Jews and Judaism was to “table it for further study”: a well-known bureaucratic prescription for a certain death.

Faced with that dire possibility, just 20 years after the murderous Holocaust in the heart of what Pope John Paul II called “Christian Europe,” many American Catholic leaders became alarmed. Cardinal Richard James Cushing, then archbishop of Boston, was fearful no action would be taken on the critical issues of deicide and anti-Semitism. He felt an urgent need to express his concerns in person in Rome.

Cushing led the forces not only of the United States but of all Catholics, recruiting similar positive views from other parts of the globe. He especially wanted to speak personally to his brother bishops assembled in Rome during the Vatican Council.

His focus was on the need for his beloved church to rid itself of anti-Semitism, a terrible prejudice that defamed Jews and debilitated Roman Catholics everywhere. Cushing, who always hated leaving his beloved Boston, nonetheless traveled to Rome and delivered the greatest speech of his life on Sept. 28, 1964.

The cardinal’s remarks, given in St. Peter’s Basilica, were delivered in Latin with Cushing’s raspy, heavy New England accent. It drew wide attention and exhilarated many of his fellow bishops. One observer recalled that the Bostonian’s strong voice overwhelmed the microphones and echoed throughout the basilica.

Cardinal Richard Cushing in the 1960s. Copyright City of Boston

When he finished speaking, his rapt audience applauded Cushing. I strongly believe his powerful heartfelt words saved “Nostra Aetate” from oblivion.

In a time of increased acts of anti-Semitism in the United States, Europe and other parts of the world, Cushing’s words resonate today, more than a half-century later: “ … How many (Jews) have suffered in our own time? How many died because Christians were indifferent or kept silent? If in recent years, not many Christian voices were raised against those injustices, at least let ours now be heard in humility.”

We must, he continued, “foster a special reverence and love for the children of Abraham. … (Jews) are Christ’s blood relatives. … (We cannot) burden … generations of Jews with any burden of guilt for the crucifixion of the Lord Jesus. … In clear and unmistakable language, we must deny that the Jews are guilty of our Savior’s death.”

He concluded, “In this august assembly, in this solemn moment, we must cry out: There is no Christian rationale — neither theological nor historical — for any iniquity, hatred or persecution of our Jewish brothers. … Great is the hope … that this sacred synod will make such a fitting declaration … ”

His speech was widely reported and his portrait appeared on the cover of Time magazine, a recognition at the time of his personal leadership.

Thanks in great part to the efforts of Cushing and other American Catholic leaders, exactly 13 months after Cushing’s speech, the Vatican Council did, in fact, ” … make a fitting declaration” that would not have happened without the Boston cardinal’s leadership.

(Rabbi A. James Rudin is the American Jewish Committee’s senior interreligious adviser and the author of “Cushing, Spellman, O’Connor: The Surprising Story of How Three American Cardinals Transformed Catholic-Jewish Relations.” He can be reached at jamesrudin.com. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)