Russia's Shadow Fleet Tactics Exposed

PUBLISHED JUN 23, 2024 9:10 PM BY GIANGIUSEPPE PILI, ALESSIO ARMENZONI AND GARY KESSLER

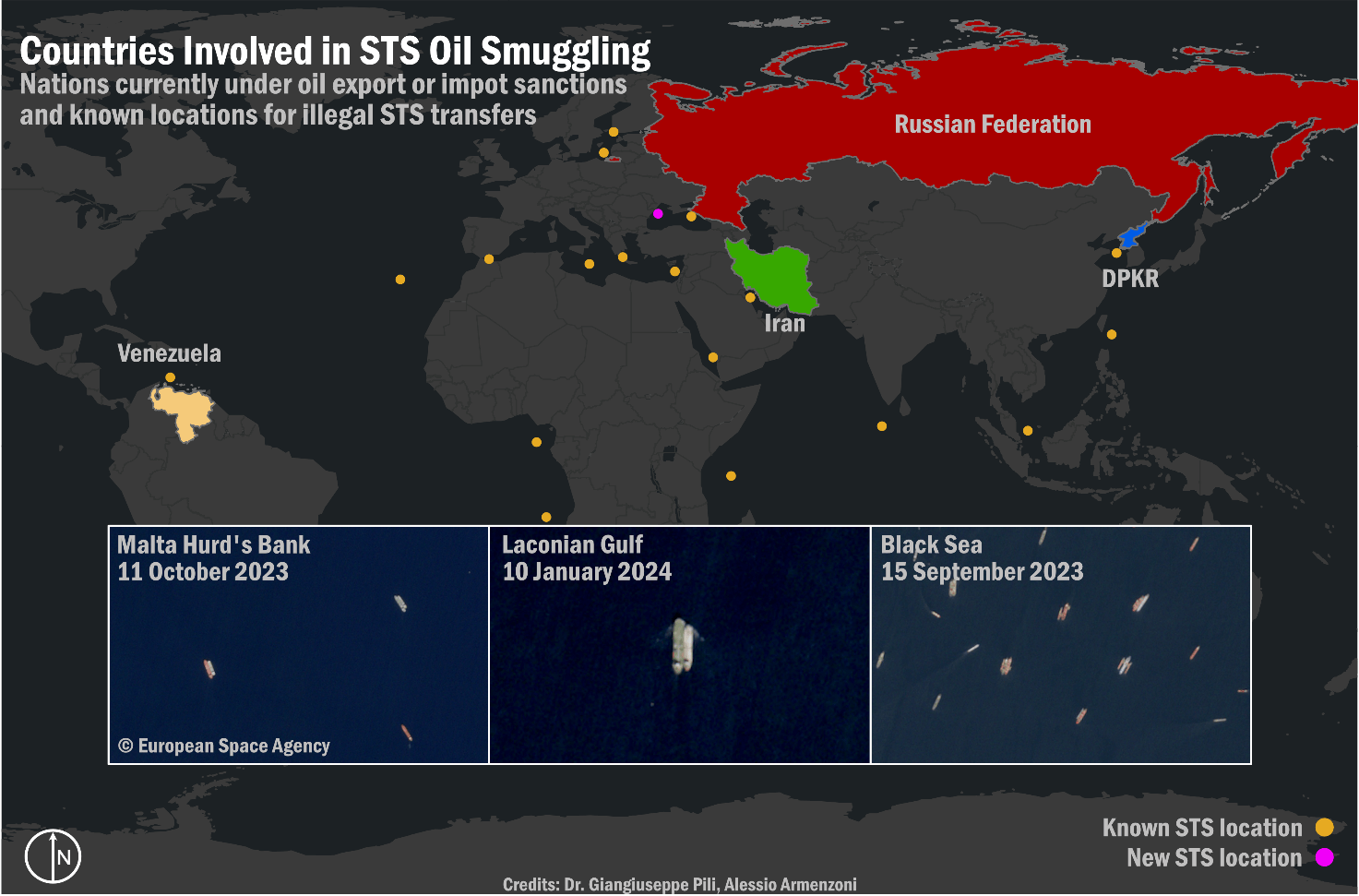

Russia’s shadow fleet is moving oil into four different areas in the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea, according to a recent report in the U.S Naval Institute’s Proceedings. The oil is moved through a complicated net of ship-to-ship (STS) transfers. The so-called shadow fleet is a collection of aging and weathered tankers with unknown or shady insurers, and it is helping Russia evade Western-imposed sanctions on shipping.

The Russian Federation’s main source of income comes from fuel and energy exports. Following the invasion of Ukraine and the ban of Russian oil sold above a price cap, the Kremlin had to find a way to keep the oil flowing out. Russian interests created a parallel, sanction-proof fleet able to move millions of barrels per day.

The shadow fleet relies on ship-to-ship (STS) transfers in order to mask the source of Russian oil. The locations identified as STS transshipment areas include the Laconian Gulf, Hurd’s Bank near Malta, an area off Ceuta, and a suspicious spot off the coast of Romania. In these locations, tankers carrying Russian crude and oil products usually meet up and engage in STS transfers. With this sanctions-evasion behavior, Western-insured tankers can carry oil or products priced above the G7 price cap on Russian oil, and therefore earn from the shipments. At the same time, the Russian Federation can keep its exports flowing to pay for their war in Ukraine.

Fig. 1: Countries Involved in STS operations. Sources: Lloyd’s List Intelligence, Windward, European Space Agency, Authors.

Fig. 1: Countries Involved in STS operations. Sources: Lloyd’s List Intelligence, Windward, European Space Agency, Authors.

Technically, moving Russian oil is not entirely illegal. If the oil is purchased below a certain threshold, which is $60 per barriel for crude (and $45 and $100 for discount and premium oil products, respectively), Western-insured tankers can ship this cargo. The measure has been taken in order to prevent global energy prices from skyrocketing, at the same time, to limit the Kremlin’s revenues. However, Urals oil has been trading significantly above the threshold since July 2023, and so has the ESPO blend, which never went under the price cap. With these oil prices, there is a heightened need for sanctions compliance monitoring and due diligence.

There are many cases where Western-insured oil tankers loaded crude or products in Russian ports at times when oil prices were – and are – above the limit, making it difficult to assess if the shipping were legal. Moreover, since transaction prices are available only to brokers and traders, to assess if a delivery is compliant is more difficult than it may appear. However, the fluctuation of oil prices may be helpful to give a general indication.

If this is combined with Identification Deception Tactics, such as spoofing or AIS blackouts, the shady nature of the transshipments appears evident. Indeed, there are many tactics employed by Russian-related tankers, ranging from AIS disappearance to spoofing, but especially the blending of oil in floating oil hubs or storage; shady tankers loitering in known transfer areas; and receiving cargo from different countries. After the blending procedure, the oil is then transferred to other ships that, as a result, don’t have to prove any attestation of compliance – since the oil is no longer labeled as Russian.

In all of this, the often under-maintained tankers are dangerous environmental time bombs ready to explode, as the case of the Pablo or the more recent case of Andromeda Star remind us. New upcoming sanctions of the European Union and the United States are expected to fix some of the loopholes exploited by the so-called Shadow fleet and the STS transfers, but the numbers are so high that constant monitoring is needed.

More detailed insights into the operation of the Russian shadow fleet may be found in the author's recent USNI Proceedings article, available here.

Alessio Armenzoni is a geospatial intelligence analyst working on projects related to maritime security. He studied at the Centre for Higher Defense Studies from the Italian MoD.

Giangiuseppe Pili (Ph. D.) is an Assistant Professor in the Intelligence Analysis Program at James Madison University. He is an Associate Fellow at Open Source Intelligence and Analysis at the Royal United Services Institute.

Gary C. Kessler, Ph.D, CISSP is co-author of "Maritime Cybersecurity," 2/e and a maritime cybersecurity researcher and consultant. He is on the advisory board of Cydome and a principal consultant at Fathom5.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.

No comments:

Post a Comment