Revealed: the US is averaging one chemical accident every two days

Guardian analysis of data in light of Ohio train derailment shows accidental releases are happening consistently

Mike DeWine, the Ohio governor, recently lamented the toll taken on the residents of East Palestine after the toxic train derailment there, saying “no other community should have to go through this”.

But such accidents are happening with striking regularity. A Guardian analysis of data collected by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and by non-profit groups that track chemical accidents in the US shows that accidental releases – be they through train derailments, truck crashes, pipeline ruptures or industrial plant leaks and spills – are happening consistently across the country.

By one estimate these incidents are occurring, on average, every two days.

“These kinds of hidden disasters happen far too frequently,” Mathy Stanislaus, who served as assistant administrator of the EPA’s office of land and emergency management during the Obama administration, told the Guardian. Stanislaus led programs focused on the cleanup of contaminated hazardous waste sites, chemical plant safety, oil spill prevention and emergency response.

In the first seven weeks of 2023 alone, there were more than 30 incidents recorded by the Coalition to Prevent Chemical Disasters, roughly one every day and a half. Last year the coalition recorded 188, up from 177 in 2021. The group has tallied more than 470 incidents since it started counting in April 2020.

The incidents logged by the coalition range widely in severity but each involves the accidental release of chemicals deemed to pose potential threats to human and environmental health.

In September, for instance, nine people were hospitalized and 300 evacuated in California after a spill of caustic materials at a recycling facility. In October, officials ordered residents to shelter in place after an explosion and fire at a petrochemical plant in Louisiana. In November, more than 100 residents of Atchinson, Kansas, were treated for respiratory problems and schools were evacuated after an accident at a beverage manufacturing facility created a chemical cloud over the town.

Among multiple incidents in December, a large pipeline ruptured in rural northern Kansas, smothering the surrounding land and waterways in 588,000 gallons of diluted bitumen crude oil. Hundreds of workers are still trying to clean up the pipeline mess, at a cost pegged at around $488m.

The precise number of hazardous chemical incidents is hard to determine because the US has multiple agencies involved in response, but the EPA told the Guardian that over the past 10 years, the agency has “performed an average of 235 emergency response actions per year, including responses to discharges of hazardous chemicals or oil”. The agency said it employs roughly 250 people devoted to the EPA’s emergency response and removal program.

‘Live in daily fear of an accident’

The coalition has counted 10 rail-related chemical contamination events over the last two and a half years, including the derailment in East Palestine, where dozens of cars on a Norfolk Southern train derailed on 3 February, contaminating the community of 4,700 people with toxic vinyl chloride.

The vast majority of incidents, however, occur at the thousands of facilities around the country where dangerous chemicals are used and stored.

“What happened in East Palestine, this is a regular occurrence for communities living adjacent to chemical plants,” said Stanislaus. “They live in daily fear of an accident.”

In all, roughly 200 million people are at regular risk, with many of them people of color, or otherwise disadvantaged communities, he said.

There are close to 12,000 facilities across the nation that have on site “extremely hazardous chemicals in amounts that could harm people, the environment, or property if accidentally released”, according to a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report issued last year. These facilities include petroleum refineries, chemical manufacturers, cold storage facilities, fertilizer plants and water and wastewater treatment plants, among others.

EPA data shows more than 1,650 accidents at these facilities in a 10-year span between 2004 and 2013, roughly 160 a year. More than 775 were reported from 2014 through 2020. Additionally, after analyzing accidents in a recent five-year period, the EPA said it found accident-response evacuations impacted more than 56,000 people and 47,000 people were ordered to “shelter-in-place.”

Accident rates are particularly high for petroleum and coal manufacturing and chemical manufacturing facilities, according to the EPA. The most accidents logged were in Texas, followed by Louisiana and California.

Though industry representatives say the rate of accidents is trending down, worker and community advocates disagree. They say incomplete data and delays in reporting incidents give a false sense of improvement.

The EPA itself says that by several measurements, accidents at facilities are becoming worse: evacuations, sheltering and the average annual rate of people seeking medical treatment stemming from chemical accidents are on the rise. Total annual costs are approximately $477m, including costs related to injuries and deaths.

“Accidental releases remain a significant concern,” the EPA said.

In August, the EPA proposed several changes to the Risk Management Program (RMP) regulations that apply to plants dealing with hazardous chemicals. The rule changes reflect the recognition by EPA that many chemical facilities are located in areas that are vulnerable to the impacts of the climate crisis, including power outages, flooding, hurricanes and other weather events.

The proposed changes include enhanced emergency preparedness, increased public access to information about hazardous chemicals risks communities face and new accident prevention requirements.

The US Chamber of Commerce has pushed back on stronger regulations, arguing that most facilities operate safely, accidents are declining and that the facilities impacted by any rule changes are supplying “essential products and services that help drive our economy and provide jobs in our communities”. Other opponents to strengthening safety rules include the American Chemistry Council, American Forest & Paper Association, American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers and the American Petroleum Institute.

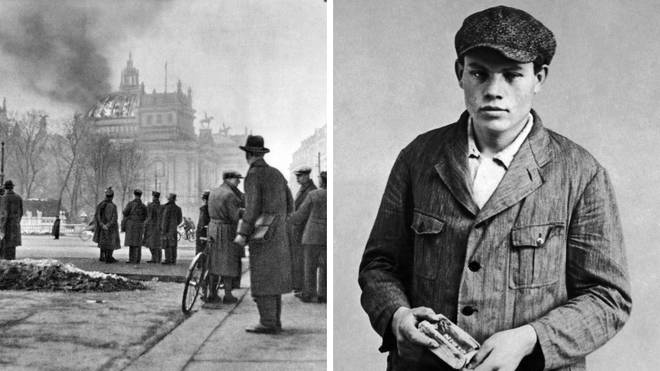

View of the site of the derailment of a train carrying hazardous waste in East Palestine, Ohio. Photograph: Alan Freed/Reuters

The changes are “unnecessary” and will not improve safety, according to the American Chemistry Council.

Many worker and community advocates, such as the International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace & Agricultural Implement Workers of America, (UAW), which represents roughly a million laborers, say the proposed rule changes don’t go far enough..

And Senator Cory Booker and US Representative Nanette Barragan – along with 47 other members of Congress - also have called on the EPA to strengthen regulations to protect communities from hazardous chemical accidents.

“The East Palestine train derailment is an environmental disaster that requires full accountability and urgency from the federal government. We need that same urgency to focus on the prevention of these chemical disasters from occurring in the first place,” Barragan said in a statement issued to the Guardian.

‘We’re going to be ready’

For Eboni Cochran, a mother and volunteer community activist, the East Palestine disaster has hardly added to her faith in the federal government. Cochran lives with her husband and 16-year-old son roughly 400 miles south of the derailment, near a Louisville, Kentucky, industrial zone along the Ohio River that locals call “Rubbertown.” The area is home to a cluster of chemical manufacturing facilities, and curious odors and concerns about toxic exposures permeate the neighborhoods near the plants.

Cochran and her family keep what she calls “get-out-of-dodge” backpacks at the ready in case of a chemical accident. They stock the packs with two changes of clothes, protective eyewear, first aid kits and other items they think they may need if forced to flee their home.

The organization she works with, Rubbertown Emergency Action (React), wants to see continuous air monitoring near the plants, regular evacuation drills and other measures to better prepare people in the event of an accidental chemical release. But it’s been difficult to get the voices of locals heard, she says.

“Decision-makers are not bringing impacted communities to the table,” she said.

In the meantime React is trying to empower locals to be prepared to protect themselves if the worst happens. Providing emergency evacuation backpacks to people near plants is one small step.

“Even in small doses certain toxic chemicals can be dangerous. They can lead to long term chronic illness, they can lead to acute illness,” Cochran said. “If there is a big explosion, we’re going to be ready.”

This story is co-published with the New Lede, a journalism project of the Environmental Working Group.