What about Kamala?

The vice president has taken on an expanded role in the last few months. Now Biden needs her more than ever.

by Christian Paz

Christian Paz is a senior politics reporter at Vox, where he covers the Democratic Party. He joined Vox in 2022 after reporting on national and international politics for the Atlantic’s politics, global, and ideas teams, including the role of Latino voters in the 2020 election.

The vice president has taken on an expanded role in the last few months. Now Biden needs her more than ever.

by Christian Paz

Jun 28, 2024,

Vice President Kamala Harris delivers remarks on reproductive rights at Ritchie Coliseum on the campus of the University of Maryland on June 24, 2024 in College Park, Maryland, on the two-year anniversary of the Dobbs decision.

Vice President Kamala Harris delivers remarks on reproductive rights at Ritchie Coliseum on the campus of the University of Maryland on June 24, 2024 in College Park, Maryland, on the two-year anniversary of the Dobbs decision.

Kevin Dietsch/Getty

If President Joe Biden decides to drop out of the presidential race, it appears likely that his replacement at the top of the ticket would be his running mate, Vice President Kamala Harris.

Until this week, that possibility wasn’t really worth pondering too much. But after Biden’s disastrous performance during Thursday night’s debate, Harris becoming the Democratic nominee is suddenly a more serious hypothetical.

Before considering what that would actually look like, it’s helpful to take stock of her vice presidency — and vice presidential candidacy — so far. Despite frequent criticisms and confusion surrounding what exactly her job is, she is now emerging as an indispensable surrogate and defender, and maybe even successor. She hasn’t been a particularly groundbreaking vice president, but she has had moments on the campaign trail, albeit overlooked by the public and the press, when she is able to showcase her value. It’s a preview of how her role could change in the coming months and even years, whether or not Biden steps aside.

Thursday night was one of those times. As shocked and panicked reactions from Democratic operatives and the political press began to pour in post-debate, Harris was dispatched to defend Biden on CNN and MSNBC. She admitted that Biden had a “slow start,” but rounded that answer off by playing up a “strong finish” by the president. She went on offense: attacking Trump for his many lies during the debate and emphasizing Trump’s statements in defense of the January 6 insurrection and refusal to accept the results of the election.

In the process, she surprised a host of pundits who wondered why the White House has “kept her under wraps for three years.”

The answer is complicated.

Harris’s vice presidency has been muted by design

Unlike Biden’s tenure under former President Barack Obama, Harris’s role as vice president has been low-key. For most of her term, she’s been relegated to warm-up speaker and occasional Biden stand-in, delivering remarks at White House events with the president, attending summits and visiting foreign leaders when Biden is needed in DC or on another trip, or, like Thursday night, brought in to do clean-up.

Many of those back-seat responsibilities have been due to the nature of the vice presidency: a constitutional office without any clear authorities beyond being a spare body in the event the president can’t do his job and being an extra vote when the US Senate is evenly tied.

But some of it appears to have been intentional. Vice presidents have exerted influence and power before. Vice President Dick Cheney essentially ran foreign policy for a few years during George W. Bush’s first term. Biden himself was given a large mandate by Obama during the government’s response to the Great Recession, administering hundreds of billions of dollars in federal stimulus spending.

Harris got no such assignments, despite Biden suggesting that he wanted his second-in-command to be a governing “partner” during the 2020 campaign season. Questions about this have dogged Harris. Just nine months into Biden’s term, after waves of negative media coverage, public absence, staff departures, and rhetorical missteps (which have now become a genre of meme), the White House issued a statement assuring the public that the president did rely on Harris.

By that point, the idea that Harris served a superfluous role was already baking into public and media perception. Instead of working on issues like criminal-justice reform and policing — her areas of expertise — she took on voting rights, an issue that was doomed to fail in an evenly divided Senate. Her portfolio was then filled with another cursed assignment: dealing with the root causes of migration from Latin America. Mainstream press coverage of that task, and Republican framing of it online and in right-wing media, made it seem like her job would be dealing with immigration and the southern border, however. That fog made her an easier target for Republicans.

Still, something changed in 2022: When the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade that summer and eliminated the constitutional right to an abortion, Harris suddenly had a clear lane in which to operate, and she has taken it: being the Biden administration’s point person on conservative threats to reproductive rights.

Campaign-trail Harris has shown how much of an asset she could be

Post-Dobbs and since the generally successful midterms that followed later that same year, Harris’s official role has shifted. She’s been on more foreign visits and to gatherings of NATO and allied leaders, headlined a national college tour, and embarked on two other nationwide tours: one this winter dedicated to raising awareness of threats to reproductive freedom (it kicked off on the 51st anniversary of Roe v. Wade) and another this spring focused on “economic opportunity.”

The tours, though events run out of the White House, served a campaign function as well. The stops were concentrated in swing states, and meant to reach a swath of core Democratic constituencies that Harris may be better positioned to speak to like young voters and college students, women, Black and Latino Americans, and working-class communities. Unlike Biden, who has been struggling with voters from all of these backgrounds, Harris is a natural communicator in these settings.

The change in these official duties has also resulted in a shift in her campaign role, especially as the primary season wrapped up this spring and the general election began. She made history, the White House said, when she visited and toured an abortion clinic in Minneapolis in March, and has since delivered campaign speeches in states that have taken measures to restrict abortion access, like Florida and Arizona, both when the state’s top court allowed a century-old abortion ban go into effect and again on the second anniversary of Dobbs.

She’s also been zeroing in on other progressive priorities like gun safety, student loan forgiveness, and the war in Gaza. She’s been engaging media and giving many more interviews than Biden, appearing as a guest on popular podcasts, TV shows like The Drew Barrymore Show and Jimmy Kimmel Live!, and online talk shows to discuss the White House and the Biden campaign’s priorities.

She’s filling the void that Biden has created intentionally (because of his age) or not (because he is also president, governing the country). Thursday night’s interviews, and whatever appearances she will have to make to defend Biden, show us what is likely to come: an expanded role for the veep in this term and a theoretical next.

Biden will need it and Democrats should want it, in the event that Harris has to step up to win the election, govern the nation, or just be a solid backup — precisely as the vice presidency is supposed to work.

If President Joe Biden decides to drop out of the presidential race, it appears likely that his replacement at the top of the ticket would be his running mate, Vice President Kamala Harris.

Until this week, that possibility wasn’t really worth pondering too much. But after Biden’s disastrous performance during Thursday night’s debate, Harris becoming the Democratic nominee is suddenly a more serious hypothetical.

Before considering what that would actually look like, it’s helpful to take stock of her vice presidency — and vice presidential candidacy — so far. Despite frequent criticisms and confusion surrounding what exactly her job is, she is now emerging as an indispensable surrogate and defender, and maybe even successor. She hasn’t been a particularly groundbreaking vice president, but she has had moments on the campaign trail, albeit overlooked by the public and the press, when she is able to showcase her value. It’s a preview of how her role could change in the coming months and even years, whether or not Biden steps aside.

Thursday night was one of those times. As shocked and panicked reactions from Democratic operatives and the political press began to pour in post-debate, Harris was dispatched to defend Biden on CNN and MSNBC. She admitted that Biden had a “slow start,” but rounded that answer off by playing up a “strong finish” by the president. She went on offense: attacking Trump for his many lies during the debate and emphasizing Trump’s statements in defense of the January 6 insurrection and refusal to accept the results of the election.

In the process, she surprised a host of pundits who wondered why the White House has “kept her under wraps for three years.”

The answer is complicated.

Harris’s vice presidency has been muted by design

Unlike Biden’s tenure under former President Barack Obama, Harris’s role as vice president has been low-key. For most of her term, she’s been relegated to warm-up speaker and occasional Biden stand-in, delivering remarks at White House events with the president, attending summits and visiting foreign leaders when Biden is needed in DC or on another trip, or, like Thursday night, brought in to do clean-up.

Many of those back-seat responsibilities have been due to the nature of the vice presidency: a constitutional office without any clear authorities beyond being a spare body in the event the president can’t do his job and being an extra vote when the US Senate is evenly tied.

But some of it appears to have been intentional. Vice presidents have exerted influence and power before. Vice President Dick Cheney essentially ran foreign policy for a few years during George W. Bush’s first term. Biden himself was given a large mandate by Obama during the government’s response to the Great Recession, administering hundreds of billions of dollars in federal stimulus spending.

Harris got no such assignments, despite Biden suggesting that he wanted his second-in-command to be a governing “partner” during the 2020 campaign season. Questions about this have dogged Harris. Just nine months into Biden’s term, after waves of negative media coverage, public absence, staff departures, and rhetorical missteps (which have now become a genre of meme), the White House issued a statement assuring the public that the president did rely on Harris.

By that point, the idea that Harris served a superfluous role was already baking into public and media perception. Instead of working on issues like criminal-justice reform and policing — her areas of expertise — she took on voting rights, an issue that was doomed to fail in an evenly divided Senate. Her portfolio was then filled with another cursed assignment: dealing with the root causes of migration from Latin America. Mainstream press coverage of that task, and Republican framing of it online and in right-wing media, made it seem like her job would be dealing with immigration and the southern border, however. That fog made her an easier target for Republicans.

Still, something changed in 2022: When the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade that summer and eliminated the constitutional right to an abortion, Harris suddenly had a clear lane in which to operate, and she has taken it: being the Biden administration’s point person on conservative threats to reproductive rights.

Campaign-trail Harris has shown how much of an asset she could be

Post-Dobbs and since the generally successful midterms that followed later that same year, Harris’s official role has shifted. She’s been on more foreign visits and to gatherings of NATO and allied leaders, headlined a national college tour, and embarked on two other nationwide tours: one this winter dedicated to raising awareness of threats to reproductive freedom (it kicked off on the 51st anniversary of Roe v. Wade) and another this spring focused on “economic opportunity.”

The tours, though events run out of the White House, served a campaign function as well. The stops were concentrated in swing states, and meant to reach a swath of core Democratic constituencies that Harris may be better positioned to speak to like young voters and college students, women, Black and Latino Americans, and working-class communities. Unlike Biden, who has been struggling with voters from all of these backgrounds, Harris is a natural communicator in these settings.

The change in these official duties has also resulted in a shift in her campaign role, especially as the primary season wrapped up this spring and the general election began. She made history, the White House said, when she visited and toured an abortion clinic in Minneapolis in March, and has since delivered campaign speeches in states that have taken measures to restrict abortion access, like Florida and Arizona, both when the state’s top court allowed a century-old abortion ban go into effect and again on the second anniversary of Dobbs.

She’s also been zeroing in on other progressive priorities like gun safety, student loan forgiveness, and the war in Gaza. She’s been engaging media and giving many more interviews than Biden, appearing as a guest on popular podcasts, TV shows like The Drew Barrymore Show and Jimmy Kimmel Live!, and online talk shows to discuss the White House and the Biden campaign’s priorities.

She’s filling the void that Biden has created intentionally (because of his age) or not (because he is also president, governing the country). Thursday night’s interviews, and whatever appearances she will have to make to defend Biden, show us what is likely to come: an expanded role for the veep in this term and a theoretical next.

Biden will need it and Democrats should want it, in the event that Harris has to step up to win the election, govern the nation, or just be a solid backup — precisely as the vice presidency is supposed to work.

Christian Paz is a senior politics reporter at Vox, where he covers the Democratic Party. He joined Vox in 2022 after reporting on national and international politics for the Atlantic’s politics, global, and ideas teams, including the role of Latino voters in the 2020 election.

After disastrous debate, Joe Biden can’t beat Donald Trump but there is a woman who can

Columnists

By Susan Dalgety

Published 28th Jun 2024,

By Susan Dalgety

Published 28th Jun 2024,

THE SCOTSMAN

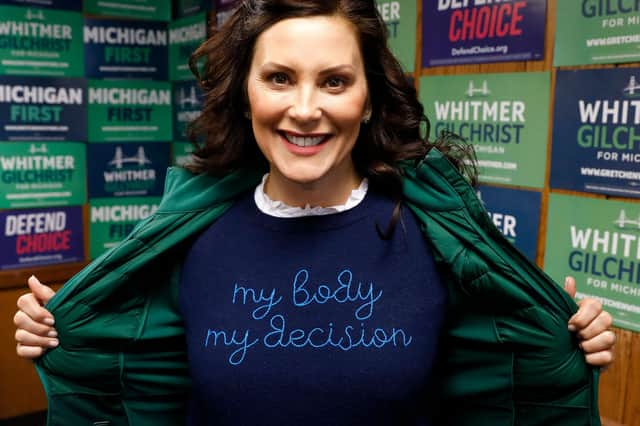

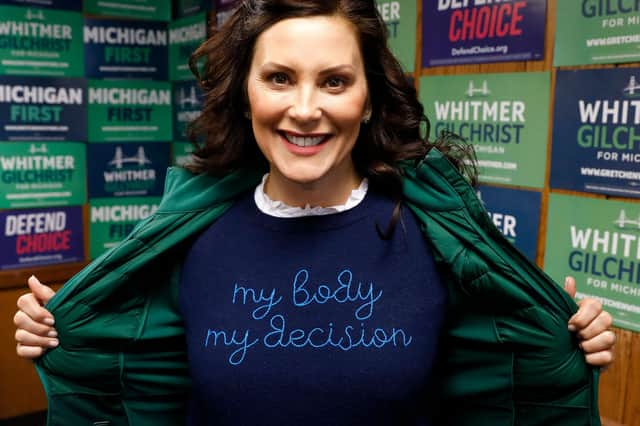

After a stumbling performance by a deathly white Joe Biden reduces Susan Dalgety to tears, she turns to the formidable Michigan governor, Gretchen Whitmer, for hope

In the late autumn of 2008, just days before Barack Obama was elected President of the United States, I spent an early Friday evening as a steward at a Joe Biden gig. The school hall in rural Pennsylvania was filled with excited Obama supporters, clutching Hope and Change placards, and chanting the campaign’s slogan “Fired Up”.

So far, so predictable. I had witnessed Obama-fever every day during the six weeks I had been volunteering in the campaign’s Bethlehem field office, and as election day approached, the excitement was reaching fever pitch, but this was first time I had seen Biden fans up close.

Clustered round the low-rise stage were scores of young, blue-collar men. Mostly white, all union men, and all very excited that they were soon going to be in the presence of Biden. I was surprised at their fervour. The campaign team I worked on was run by young middle-class liberals, many from out of state. To them, Biden was a relic of America’s industrial past – similar to the giant steel plant in south Bethlehem. It once produced the steel that built 20th century America, and was now a casino and arts complex.

After a stumbling performance by a deathly white Joe Biden reduces Susan Dalgety to tears, she turns to the formidable Michigan governor, Gretchen Whitmer, for hope

In the late autumn of 2008, just days before Barack Obama was elected President of the United States, I spent an early Friday evening as a steward at a Joe Biden gig. The school hall in rural Pennsylvania was filled with excited Obama supporters, clutching Hope and Change placards, and chanting the campaign’s slogan “Fired Up”.

So far, so predictable. I had witnessed Obama-fever every day during the six weeks I had been volunteering in the campaign’s Bethlehem field office, and as election day approached, the excitement was reaching fever pitch, but this was first time I had seen Biden fans up close.

Clustered round the low-rise stage were scores of young, blue-collar men. Mostly white, all union men, and all very excited that they were soon going to be in the presence of Biden. I was surprised at their fervour. The campaign team I worked on was run by young middle-class liberals, many from out of state. To them, Biden was a relic of America’s industrial past – similar to the giant steel plant in south Bethlehem. It once produced the steel that built 20th century America, and was now a casino and arts complex.

Biden was an avuncular figure, a Washington insider, but he was already yesterday’s man. Obama was the future. But not to the young men waiting for Uncle Joe. Biden was their hero. A man of the people. And he did not let them down. He gave a tub-thumping, old-fashioned stump speech, evoking a mythical United States of America where working class men and women were the bedrock of the world’s greatest economy. And would be again, under an Obama-Biden administration. The crowd loved it. I loved it. We were fired up, ready to go.

A much more dangerous world

In the early hours of this morning, I watched with tears in my eyes as a confused old man stumbled his way through the most important public appearance of his life. Perhaps the most important public appearance of all our lives, because if Donald Trump, a self-confessed fan of Vladimir Putin, wins the presidential election on November 5, the world will immediately become a much more dangerous place.

The spectacle of a deathly white Biden, his voice so hoarse as to be almost inaudible at times, stumbling to craft a coherent sentence will remain with me forever. It was like spending an hour or so with a much-loved grandparent, someone who was once the vital heart of the family, but now sits dazed and confused in the corner of every family gathering while life goes on around about them. Trump may be only three years younger than his rival, but at 78, he is a young-old man. Biden is just too old.

Will he stand down in time to allow the Democrats to choose another presidential candidate? He should. Even if he was to win in November – and the polls suggest he will struggle to beat Trump – he is clearly not fit to be President for another four years. He will be 82 only two weeks after the election. His body, if not his mind, is clearly worn out. He is simply not fit to be leader of the free world. But who is?

Harris would struggle

Kamala Harris, his vice president, is the obvious choice, and if she won she would be America’s first female President, but she has failed to shine as Joe’s number two. A staunch advocate for a woman’s right to choose, she has led the campaign against the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v Wade, which, according to most commentators, is the issue that has galvanised more voters, particularly women, in states run by Republicans.

Speaking in Wisconsin at the start of a national tour to mark the 51st anniversary of Roe v Wade, she stood next to a banner that screamed “TRUST WOMEN”. “These extremists want to roll back the clock to a time before women were treated as full citizens,” she said. But the polls consistently show that America, even Democrat America, does not trust this particular woman.

There is another female politician, however, who is arguably a more suitable heir to Biden, and given enough time could be a formidable challenger to Trump.

During a six-month road trip across America in 2018, when I ended up back in Bethlehem for a third election campaign – this time the mid-terms during Trump’s first administration – we drove the length of Michigan. The state is the ancestral home of America’s car industry. It also had the worst roads of any of the 35 states we spent time in.

Fix the country, save the world

One woman had had enough. Democrat Gretchen Whitmer stood for state governor on the slogan of “fix the damn roads” and stormed to victory. She was comfortably re-elected in 2022, and at 52, with six years’ experience of running a big, post-industrial state, she is surely a major contender for the top job. And Trump fears her so much that he can barely bring himself to use her name, referring to her as “that woman from Michigan”.

In a recent New York Times interview, Whitmer, who is co-chair of Biden’s re-election campaign, argued that the 2028 presidential election will be when the keys to the White House are passed to the next generation. She said: “…I’m hopeful that in 2028, we see Gen Xers running for the White House and that someone from my generation is ready to take the mantle.”

After Thursday night’s heart-breaking performance by Biden, the Democrats, America, indeed the world, must be hoping that someone from Whitmer’s generation is ready to take the mantle now, because in four years’ time. it might well be too late. Surely it is time for Gretchen Whitmer to “fix the damn country”, and save the world.

A much more dangerous world

In the early hours of this morning, I watched with tears in my eyes as a confused old man stumbled his way through the most important public appearance of his life. Perhaps the most important public appearance of all our lives, because if Donald Trump, a self-confessed fan of Vladimir Putin, wins the presidential election on November 5, the world will immediately become a much more dangerous place.

The spectacle of a deathly white Biden, his voice so hoarse as to be almost inaudible at times, stumbling to craft a coherent sentence will remain with me forever. It was like spending an hour or so with a much-loved grandparent, someone who was once the vital heart of the family, but now sits dazed and confused in the corner of every family gathering while life goes on around about them. Trump may be only three years younger than his rival, but at 78, he is a young-old man. Biden is just too old.

Will he stand down in time to allow the Democrats to choose another presidential candidate? He should. Even if he was to win in November – and the polls suggest he will struggle to beat Trump – he is clearly not fit to be President for another four years. He will be 82 only two weeks after the election. His body, if not his mind, is clearly worn out. He is simply not fit to be leader of the free world. But who is?

Harris would struggle

Kamala Harris, his vice president, is the obvious choice, and if she won she would be America’s first female President, but she has failed to shine as Joe’s number two. A staunch advocate for a woman’s right to choose, she has led the campaign against the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v Wade, which, according to most commentators, is the issue that has galvanised more voters, particularly women, in states run by Republicans.

Speaking in Wisconsin at the start of a national tour to mark the 51st anniversary of Roe v Wade, she stood next to a banner that screamed “TRUST WOMEN”. “These extremists want to roll back the clock to a time before women were treated as full citizens,” she said. But the polls consistently show that America, even Democrat America, does not trust this particular woman.

There is another female politician, however, who is arguably a more suitable heir to Biden, and given enough time could be a formidable challenger to Trump.

During a six-month road trip across America in 2018, when I ended up back in Bethlehem for a third election campaign – this time the mid-terms during Trump’s first administration – we drove the length of Michigan. The state is the ancestral home of America’s car industry. It also had the worst roads of any of the 35 states we spent time in.

Fix the country, save the world

One woman had had enough. Democrat Gretchen Whitmer stood for state governor on the slogan of “fix the damn roads” and stormed to victory. She was comfortably re-elected in 2022, and at 52, with six years’ experience of running a big, post-industrial state, she is surely a major contender for the top job. And Trump fears her so much that he can barely bring himself to use her name, referring to her as “that woman from Michigan”.

In a recent New York Times interview, Whitmer, who is co-chair of Biden’s re-election campaign, argued that the 2028 presidential election will be when the keys to the White House are passed to the next generation. She said: “…I’m hopeful that in 2028, we see Gen Xers running for the White House and that someone from my generation is ready to take the mantle.”

After Thursday night’s heart-breaking performance by Biden, the Democrats, America, indeed the world, must be hoping that someone from Whitmer’s generation is ready to take the mantle now, because in four years’ time. it might well be too late. Surely it is time for Gretchen Whitmer to “fix the damn country”, and save the world.

“It’s important to manage one’s ride into the sunset,” Radosław Sikorski said.

Joe Biden’s debate performance in the early hours of Friday was at times unintelligible. | Andrew Harnik/Getty Images

JUNE 28, 2024

BY SEB STARCEVIC

Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski took what appeared to be a shot at U.S. President Joe Biden by drawing a parallel between his widely panned debate performance against Donald Trump and the decline of the Roman empire.

Sikorski posted Friday morning on X: “It’s important to manage one’s ride into the sunset,” just hours after Biden’s stumbling debate display led to growing calls for him to pull out of the race for a second White House term.

Sikorski drew a cryptic parallel with Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, calling him “a great emperor” who “screwed up his succession” by passing the mantle to his son, Commodus, whose “disastrous rule started Rome’s decline.”

The popular idea that Marcus Aurelius’ reign marked the end of the glory days of Rome goes back to the ancient historian Cassius Dio, who said the end of his rule marked the transition “from a kingdom of gold to one of iron and rust.”

Biden’s debate performance in the early hours of Friday was at times unintelligible with a raspy voice, wandering eyes, pallid complexion and a halting delivery, sparking horror among Democratic operatives and the European media.

For Sikorski, the latest comments aren’t the first time he has courted controversy on social media.

He tweeted a photo in September 2022 of the damaged Nord Stream pipeline and captioned it “Thank You, USA,” seemingly accusing the U.S. of being involved in the sabotage of the Russia-to-Europe pipeline and earning a rebuke from his own party. He later deleted that tweet.

Sikorski’s enigmatic Marcus Aurelius tweet is still up — for now.

No comments:

Post a Comment