by University of Exeter

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

A new study on work-life balance has found that the COVID-19 crisis is a crucial factor—but not the only one—behind low levels of wellbeing among employees working from home.

A research team including Professor Ilke Inceoglu, professor of organisational behaviour and HR management at the University of Exeter Business School, analysed data from 835 university employees, who completed a baseline questionnaire on wellbeing and took a weekly survey.

The preliminary results, which are being prepared for peer review, found that around 38% of home-workers felt anxious most or all of the time while death levels went up during the early stages of the first COVID-19 lockdown, with 8% saying they felt depressed.

The handling of the pandemic by government and employers was found to make those working from home more anxious and less enthusiastic about their jobs, and job insecurity, as a result of the economic impact of lockdown, also had a negative impact on wellbeing.

But the loneliness of working in a home environment and increased demands to juggle work and domestic responsibilities also caused a decline in employee wellbeing, the study found.

Nearly one in five (17%) remote workers reported feeling lonely, while around a quarter (25.9%) said that the competing demands of work and domestic duties (including childcare) had taken their toll.

Other aspects of remote working that contributed to a lower standard of wellbeing included increased job insecurity, the unpredictability of future workloads, new ways of working and a lack of support from employers.

The research team claims that these factors not only impact on wellbeing but also hamper employees' ability to make decisions and concentrate—15% said they found it hard to make many decisions on their own and 21% could not decide how to go about doing their work.

Professor Inceoglu said: "Our research is important in that it adds to the story of COVID but it also enables us to assess the role of location and whether the COVID-19 pandemic factors over and above conventional job design factors, which is indeed not the case."

Professor Stephen Wood, from the University of Leicester Business School and Principle Investigator of the study, added: "The pandemic has contributed to short term fluctuations in the wellbeing of employees working at home, but the factors that affect all jobs, the extent of job discretion, potential loneliness of working alone, and job insecurity remain important and is likely to remain so after the pandemic."

The results of the study were presented at an ESRC Festival of Social Science webinar on Friday 13 November.

Explore further The future of work is flexible, says new study

Provided by University of Exeter

A new study on work-life balance has found that the COVID-19 crisis is a crucial factor—but not the only one—behind low levels of wellbeing among employees working from home.

A research team including Professor Ilke Inceoglu, professor of organisational behaviour and HR management at the University of Exeter Business School, analysed data from 835 university employees, who completed a baseline questionnaire on wellbeing and took a weekly survey.

The preliminary results, which are being prepared for peer review, found that around 38% of home-workers felt anxious most or all of the time while death levels went up during the early stages of the first COVID-19 lockdown, with 8% saying they felt depressed.

The handling of the pandemic by government and employers was found to make those working from home more anxious and less enthusiastic about their jobs, and job insecurity, as a result of the economic impact of lockdown, also had a negative impact on wellbeing.

But the loneliness of working in a home environment and increased demands to juggle work and domestic responsibilities also caused a decline in employee wellbeing, the study found.

Nearly one in five (17%) remote workers reported feeling lonely, while around a quarter (25.9%) said that the competing demands of work and domestic duties (including childcare) had taken their toll.

Other aspects of remote working that contributed to a lower standard of wellbeing included increased job insecurity, the unpredictability of future workloads, new ways of working and a lack of support from employers.

The research team claims that these factors not only impact on wellbeing but also hamper employees' ability to make decisions and concentrate—15% said they found it hard to make many decisions on their own and 21% could not decide how to go about doing their work.

Professor Inceoglu said: "Our research is important in that it adds to the story of COVID but it also enables us to assess the role of location and whether the COVID-19 pandemic factors over and above conventional job design factors, which is indeed not the case."

Professor Stephen Wood, from the University of Leicester Business School and Principle Investigator of the study, added: "The pandemic has contributed to short term fluctuations in the wellbeing of employees working at home, but the factors that affect all jobs, the extent of job discretion, potential loneliness of working alone, and job insecurity remain important and is likely to remain so after the pandemic."

The results of the study were presented at an ESRC Festival of Social Science webinar on Friday 13 November.

Explore further The future of work is flexible, says new study

Provided by University of Exeter

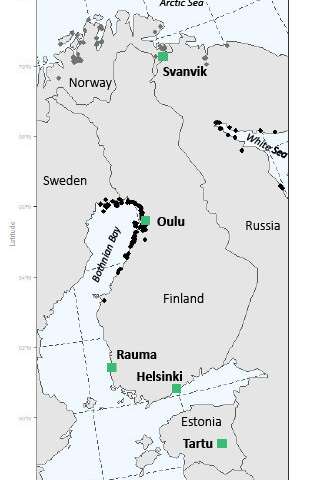

Five botanical gardens in which Siberian primroses from Norway and Finland were planted. Credit: University of Helsinki

Five botanical gardens in which Siberian primroses from Norway and Finland were planted. Credit: University of Helsinki

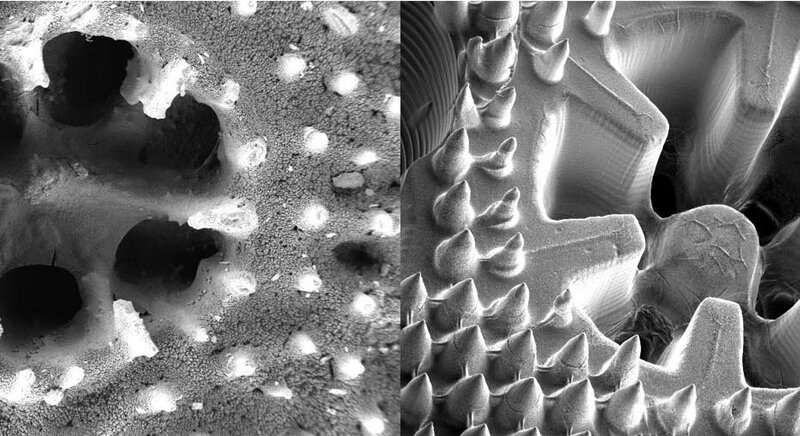

The structure of coral polyps provide an ideal habitat for colonies of Symbiodinium sp. algae to grow. Credit: Dr Wangpraseurt

The structure of coral polyps provide an ideal habitat for colonies of Symbiodinium sp. algae to grow. Credit: Dr Wangpraseurt