1 of 20 https://tinyurl.com/ydaj3cmh

TULSA, Okla. (AP) — President Donald Trump’s supporters faced off with protesters shouting “Black Lives Matter” Saturday in Tulsa as the president took the stage for his first campaign rally in months amid public health concerns about the coronavirus and fears that the event could lead to violence in the wake of killings of Black people by police.

Hundreds of demonstrators flooded the city’s downtown streets and blocked traffic at times, but police reported just a handful of arrests. Many of the marchers chanted, and some occasionally got into shouting matches with Trump supporters, who outnumbered them and yelled, “All lives matter.”

Later in the evening, a group of armed men began following the protesters. When the protesters blocked an intersection, a man wearing a Trump shirt got out of a truck and spattered them with pepper spray.

When demonstrators approached a National Guard bus that got separated from its caravan, Tulsa police officers fired pepper balls to push back the crowd, said Tulsa police spokesperson Capt. Richard Meulenberg. Officers soon left the area as it cleared.

The Trump faithful gathered inside the 19,000-seat BOK Center for what was believed to be the largest indoor event in the country since restrictions to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus began in March. Many of the president’s supporters weren’t wearing masks, despite the recommendation of public health officials. Some had been camped near the venue since early in the week.

Turnout at the rally was lower than the campaign predicted, with a large swath of standing room on the stadium floor and empty seats in the balconies. Trump had been scheduled to appear at a rally outside of the stadium within a perimeter of tall metal barriers, but that event was abruptly canceled.

Trump campaign officials said protesters prevented the president’s supporters from entering the stadium. Three Associated Press journalists reporting in Tulsa for several hours leading up to the president’s speaking did not see protesters block entry to the area where the rally was held.

While Trump spoke onstage, protesters carried a papier-mache representation of him with a pig snout. Some in the multiracial group wore Black Lives Matter shirts, others sported rainbow-colored armbands, and many covered their mouths and noses with masks. At one point, several people stopped to dance to gospel singer Kirk Franklin’s song “Revolution.”

The protesters blocked traffic in at least one intersection. Some Black leaders in Tulsa had said they were worried the visit could lead to violence. It came amid protests over racial injustice and policing across the U.S. and in a city that has a long history of racial tension. Officials had said they expected some 100,000 people downtown.

A woman who was arrested on live television was seen sitting cross-legged on the ground in peaceful protest when officers pulled her away by the arms and later put her in handcuffs. She said her name was Sheila Buck and that she was from Tulsa.

Police said in a news release the officers tried for several minutes to talk Buck into leaving and that she was taken into custody for obstruction after the Trump campaign asked police to remove her from the area.

Buck was wearing a T-shirt that said “I Can’t Breathe” — the dying words of George Floyd, whose death has inspired a global push for racial justice. She said she had a ticket to the Trump rally and was told she was being arrested for trespassing. She said she was not part of any organized group.

Several blocks away from the BOK Center was a festival-like atmosphere, with food vendors serving hot dogs and cold drinks and sidewalks lined with people selling various Trump regalia.

There was also an undercurrent of tension near the entrance to the secured area, where Trump supporters and opponents squared off. Several downtown businesses boarded up their windows as well to avoid any potential damage.

Kieran Mullen, 60, a college professor from Norman, Oklahoma, held a sign that read “Black Lives Matter” and “Dump Trump.”

“I just thought it was important for people to see there are Oklahomans that have a different point of view,” Mullen said of his state, which overwhelmingly supported Trump in 2016.

Brian Bernard, 54, a retired information technology worker from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, sported a Trump 2020 hat as he took a break from riding his bicycle around downtown. Next to him was a woman selling Trump T-shirts and hats, flying a “Keep America Great Again” flag. Her shirt said, “Impeach this,” with an image of Trump extending his middle fingers

“Since the media won’t do it, it’s up to us to show our support,” said Bernard, who drove nine hours to Tulsa for his second Trump rally.

Bernard said he wasn’t concerned about catching the coronavirus at the event and doesn’t believe it’s “anything worse than the flu.”

Across the street, armed, uniformed highway patrol troopers milled about a staging area in a bank parking lot with dozens of uniformed National Guard troops.

Tulsa has seen cases of COVID-19 spike in the past week, and the local health department director asked that the rally be postponed. But Republican Gov. Kevin Stitt said it would be safe. The Oklahoma Supreme Court on Friday denied a request that everyone attending the indoor rally wear a mask, and few in the crowd outside Saturday were wearing them.

The Trump campaign said six staff members helping prepare for the event tested positive for COVID-19. They were following “quarantine procedures” and wouldn’t attend the rally, said Tim Murtaugh, the campaign’s communications director.

Inside the barriers, the campaign was handing out masks and said hand sanitizer also would be distributed and that participants would undergo a temperature check. But there was no requirement that participants use the masks.

Teams of people wearing goggles, masks, gloves and blue gowns were checking the temperatures of those entering the rally area. Those who entered the secured area were given disposable masks, which most people wore as they went through the temperature check. Some took them off after the check.

The rally originally was planned for Friday, but was moved after complaints that it coincided with Juneteenth, which marks the end of slavery in the U.S., and in a city that was the site of a 1921 race-related massacre, when a white mob attacked Black people, leaving as many as 300 people dead.

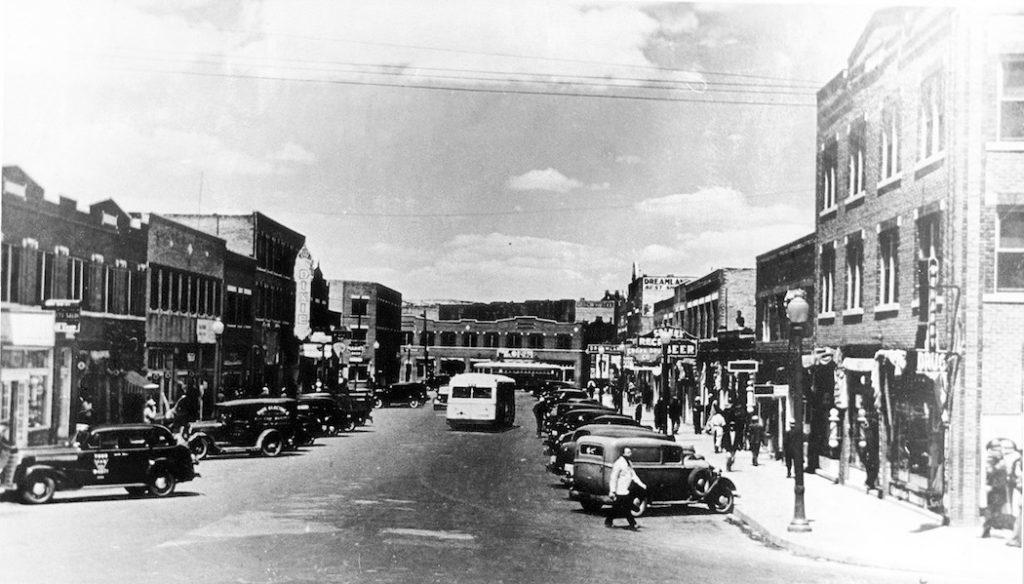

Stitt joined Vice President Mike Pence for a meeting Saturday with Black leaders from Tulsa’s Greenwood District, the area once known as “Black Wall Street” where the 1921 attack occurred. Stitt initially invited Trump to tour the area, but said, “We talked to the African American community and they said it would not be a good idea, so we asked the president not to do that.”

Associated Press reporters Ellen Knickmeyer in Tulsa, Ken Miller in Oklahoma City, Sara Burnett in Chicago, Adam Kealoha Causey in Dallas and Grant Schulte in Omaha, Nebraska, contributed to this report.