The Battle for Income Equality

Questioning the statistics in Thomas Piketty’s best-selling book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, with intent to undermine his thesis, is futile. Even if Piketty’s alert that returns on investment have exceeded the real growth of wages and economic output, which means that the stock of capital is rising faster than overall economic output, is not exactly accurate, criticism has not upset the conclusions ─ severe income inequality and inequitable wealth distribution doom the capitalist system to collapse and a more narrow wealth distribution keeps it going.

Progressive economists connect meager wage growth to limited purchasing power ─ one cause of the 2008 crash ─ and increased concentration of wealth to cautious job growth in the post-crash years. Their conclusions have engineered debates on how to achieve equitable distributions in wages and wealth and raise middle-class wages, and the roles private industry, government, and labor unions play in achieving a more equitable society.

If private industry refuses to meet its obligations to readjust the divide, Thomas Piketty recommends increasing taxes on high earners and large estates and coupling them with a wealth tax. This method for resolving income inequality gives government a major role in correcting the unequal distributions of income and wealth.

In previous decades, unions had a larger membership, greater clout, and more strength to move management to meet wage demands. Government lacks a mechanism to force corporations to transfer productivity gains into wage gains. Only corporations can do the trick. Not likely. Corporations do not realize the social and economic benefits of decreasing income inequality and increasing middle-class purchasing power. Lowering remunerations to those in top pay brackets and increasing them for lower-income workers is more than a moral obligation; it has direct benefits to the economy for everyone. It is a requirement for achieving a stable economy.

Social costs due to less equitable income and wealth distributions

Rationalizing poorly distributed wealth by noting the American poor are wealthier than the middle class in many developed nations is deceiving. Poverty is defined as an absolute number but its effects are relative. The lower wage earners in the United States are unaware of what they earn in relation to foreigners; they are aware of what they do not earn in relation to others living close to them. The wide disparity in wealth creates resentment and tension and leads to psychological and emotional difficulties. Minimizing social problems means combining giving more to the lower classes and taking less by the upper classes.

The social problems and associated costs in developed nations that have wide distributions of income and wealth are well-documented — elevated mental illness, crime, infant mortality, and health problems. One statistical proof is that the United States, classified as the most unequal of the developed nations, except Singapore, had the highest index of social problems. The graph below from 2010-2011 and an earlier article, Health is a Socio-Economic Problem, describe the important relationships.

Every citizen suffers from and pays for the social problems derived from income inequality, an unfair condition in a democratic society. Private industry has an obligation and an opportunity to fix the problem it has caused. If not, Uncle Sam, whom they don’t want on their backs, will reach into their pockets, redistribute the wealth and resolve the situation.

Income inequality produces wealth concentration and political consequences. Wealthy individuals have increased control of the political debate, more influence in selection of candidates, tend to place their interests before national interests, and determine the direction of political campaigns. Skewing the electoral process distorts government and the decisions that guide social and economic legislation. Severe disparities in the concentration of wealth reduce democratic prerogatives, fair elections, and equality before the law.

The Sunlight Foundation, in an article, The Political 1% of the 1% in 2012 by Lee Dustman, June 2013, presents a fact-filled discussion of this topic.

Note: Although statistics are from ten years ago, they are interesting statistics and are relevant today.

More than a quarter of the nearly $6 billion in contributions from identifiable sources in the last campaign cycle came from just 31,385 individuals, a number equal to one ten-thousandth of the U.S. population.

Of the 1% of the 1%’s $1.68 billion in the 2012 cycle, $500.4 million entered the campaign through a super PAC (including almost $100 million from just one couple, Sheldon and Miriam Adelson). Four out of five 1% of the 1% donors were pure partisans, giving all of their money to one party or the other.

These concerns are likely even more acute for the two parties. In 2012, the National Republican Senatorial Committee raised more than half (54.2 percent) of its $105.8 million from the 1% of the 1%, and the National Republican Congressional Committee raised one third (33.0 percent) of its $140.6 million from the 1% of the 1%. Democratic party committees depend less on the 1% of the 1%. The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee raised 12.9 percent of its $128.9 million from these top donors, and the Democratic Congressional Committee raised 20.1 percent of its $143.9 million from 1% of the 1% donors.

To the many billionaires who are tilting election campaigns, add the political contributions by super-sized corporations and industries, and electoral control by the wealthy becomes complete. Campaign contributions from the financial sector, the same financial sector that increased its liabilities from 10 percent of GDP in 1970 to 120 percent of GDP in 2009, and shifted investment from manufacturing to rent-seeking ─ making money the new-fashioned way ─ leads the way.

The Sunlight Foundation article also states:

In 1990, 1,091 elite donors in the FIRE sector (finance, insurance, and real estate).contributed $15.4 million to campaigns ─ a substantial sum at the time. But that’s nothing compared to what they contributed later. In 2010, 5,510 elite donors from the sector contributed $178.2 million, more than 10 times the amount they contributed in 1990.

The Debt of each sector as a percentage of GDP tells the story of the financial sector.

Note: 2022 GDP = $25.4T

2022 Q4 Debt at the following:

Total = $89.5T, Household = $19.4T, Business = $20.8T, Finance = $19.3T, Government= $26.8

2022 Percent of GDP at the following:

Household = 72.4%, Business = 81.9%, Finance = 76.8%, Government= 105.5%

The graph shows that the FIRE sector increased its wealth by borrowing money, making the economy work for it rather than working for the economy. The credit enabled the financial industry to grow until it led the nation into the 2008 economic disaster.

The Economic Consequences of Wealth Concentration

What has occurred with wealth concentration? A previous decade indicated a deflection of investment from dynamic industrial processes to static rent situations, from industries that employ workers to make goods to industries that employ money to make money. Graphs from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) record the trend.

Note: In 2023, Financial sector employment was 9.2M and manufacturing employment was 12.9M.

The graphs plot employment in the manufacturing and financial sectors, Manufacturing had a slow deterioration during the Reagan presidency, followed by stability during the Clinton administration and a sharp decline during the George Bush era. Some deterioration in manufacturing employment is understandable; administrative jobs (clerical, administration) have been displaced by information technologies and these fields have added jobs; factory floor work of consumer goods has been displaced by machines (robot, numerical control) that have their own factory floors; and labor has been transferred from highly labor-intensive manufacturing to service industries. However, the employment loss is excessive and bewildering when compared to the increase in financial employment. Can a healthy economy result from a steady growth in financial workers and a consistent decrease in industrial workers?

Beginning in the Reagan era, until economic collapse in 2008, employment in the financial sector monotonically increased, except for slight blips during the 1991 recession and a few years of the Clinton administration. From a ratio of 1/3 in 1986, financial sector employment rose to 2/3 that of manufacturing employment by 2014, and increased by more than the changes in their respective additions to the Gross Domestic Product. Since the 2009 mini-depression, employment in the financial industry has remained relatively static. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) shows the value added by each industry.

Manufacturing rose from $1390.1 billion in 1997 to $2079.5 billion in 2013, an increase of 50 percent.

Finance, insurance, real estate, rental, and leasing rose from $1623.1 billion in 1997 to $3293.2 billion in 2013, an increase of 100 percent.

A comparison between salaries of engineers, those who contribute directly to industrial growth, and financiers, those who drive active and passive investments, also reveals the importance given to those who make money from money.

One of the contributors to Capital, Thomas Philipson, in an article Wages and Human Capital in the U.S. Financial Industry: 1909-2006, NBER Working Paper No. 14644, January 2009, shows that wages for the financial sector started a steady growth during the Reagan administration, and eventually exceeded engineering wages, especially for those who had advanced degrees from the elite universities.

As the FIRE industry expands, the purchasing power contracts, one reason being that part of the rent-seeking covets higher returns and gets sidetracked into endless speculation; money rolling over and over and never available to purchase anything but pieces of paper. Millions of arbitrage transactions per second can earn thousands of dollars per second, which adds up to 3.6 million dollars per hour ─ no positive effect on the economy; only paper dollars continually created.

Stagnant labor wages and weak purchasing power force expansion of credit to increase demand, The wealthy respond to credit expansion with accelerated demand for larger houses, larger cars, and more luxury goods, spending that raises asset values and places middle-class earners at a disadvantage. The bottom ninety percent on the income scale desperately pursue debt to give themselves a temporary share of prosperity. Debt must eventually be repaid. Real wealth remains with a privileged few and others remain stagnant.

What is the Result?

Thomas Piketty has reshaped the thinking of the Capitalist system. Economics enables the understanding of how and when to increase demand, enable sufficient purchasing power, and the true meaning of profit. A better understanding of economics may come from less regard for the conventional economics of modern theorists and more regard for the classical economics of the fathers of political economy ─ Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Karl Marx. The latter provided a controversial concept ─ wages provide purchasing power, and beyond what is bought by that purchasing power is surplus, whose value allows profit.

Piketty shows that profits are being sidetracked into passive investments that produce only more capital and not useful goods, into the accumulation of excessive personal wealth, and into financial speculation that features the constant churning of paper money, which removes dollars from the market and creates difficulties for manufacturing to grow. Accumulation of excessive wealth generates social problems, diminishes the quality of life, and burdens the middle class when taxes are used to seek relief.

Capturing the political system by those most responsible for the problems ─ the privileged wealthy who manipulate a portion of the electoral process for their advantage ─ hinders routes to ameliorating the deterrents to a fair and successful economy. Due to their financial and political clout, the wealthy have their voices more easily heard in Congress and before federal agencies.

Karl Marx claimed that Capitalism contains the seeds of its destruction. Those who foster severe income inequality and inequitable wealth distribution apparently want to prove his statement is correct.

Dan Lieberman publishes commentaries on foreign policy, economics, and politics at substack.com. He is author of the non-fiction books A Third Party Can Succeed in America, Not until They Were Gone, Think Tanks of DC, The Artistry of a Dog, and a novel: The Victory (under a pen name, David L. McWellan). Read other articles by Dan.

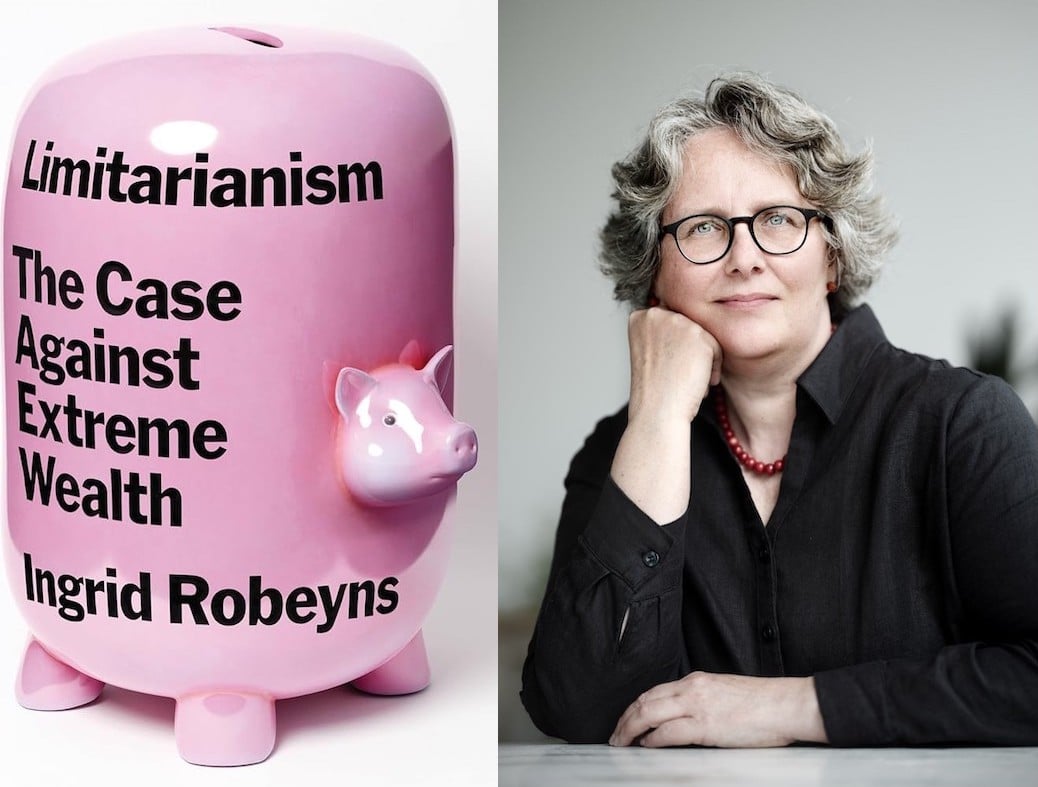

Imagine a world where Taylor Swift made just $1 million a year and saw most of her wealth taxed away to the benefit of people like the Swifties who splurge on tickets to see her perform. Would we have a more just society?

Imagine a world where Taylor Swift made just $1 million a year and saw most of her wealth taxed away to the benefit of people like the Swifties who splurge on tickets to see her perform. Would we have a more just society?