Since 1994, more than 200 people have died at the most popular lake in the Southeast.

Marquise Francis

·National Reporter

Fri, September 8, 2023

Lake Lanier in Buford, Ga., Oct. 25, 2007. (Chris Rank/ Bloomberg News)

A 23-year-old man drowned last Saturday after slipping and falling off a dock into Georgia’s Lake Lanier, according to the Georgia Department of Natural Resources (DNR). It’s the fourth death at the lake in as many weeks and the eighth this year alone — a startling number for a popular destination for fun and leisure.

With upwards of 11 million visitors each year, the 59-square-mile body of water with hundreds of miles of shoreline is the most popular lake in the Southeast. It’s also the region’s deadliest.

More than 200 people have died at Lake Lanier between 1994 and 2022, according to USA Today and Georgia DNR, with most of the deaths attributed to drownings.

Read more at Yahoo News: At least 39 drownings reported at Georgia lakes in 2023, including these at Lake Lanier

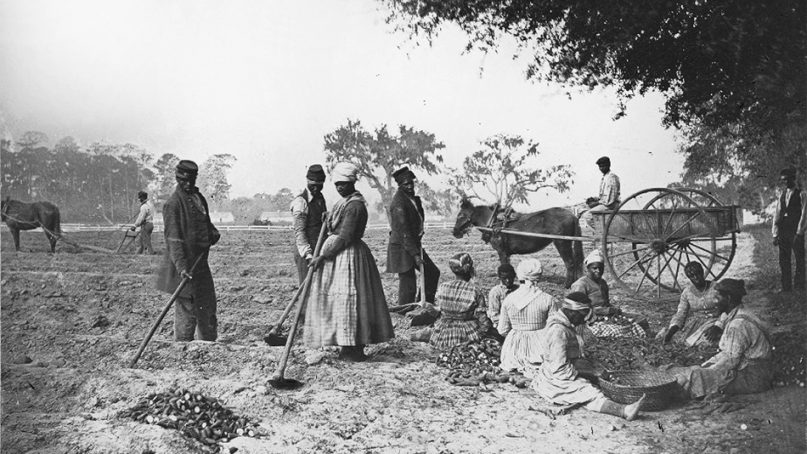

While some experts point to excessive alcohol use and the sheer volume of visitors to make sense of the growing number of deaths, many Georgia residents are quick to claim the lake is haunted due to its complex and eerie racial history. Situated northeast of Atlanta with waters up to 160-feet deep, the lake sits atop an area that was once home to a small, yet thriving, Black community in the early 1900s, until those residents were violently forced to flee.

“I don’t have to believe in ghosts to believe that a place like Lake Lanier could be haunted,” Mark Huddle, a professor at Georgia College & State University who specializes in African American history, told Yahoo News. “The haunting is that this is a place where the dark and bloody struggle for American race relations played out in a terrible way.”

A boat passes along Lake Lanier, April 23, 2013, in Buford, Ga. (David Goldman/AP)

Decades after its racial cleansing, the lush and fertile land where various Black-owned businesses and homes once stood was flooded to form what is now known as Lake Lanier.

“We are the ones who are haunted by what happened and nobody really wants to confront that history,” Huddle said.

History of Lake Lanier

Well before Lake Lanier was formed, the land it was built on was a bustling community called Oscarville, which formed in the late 1800s during the Reconstruction era. The town was majority white but had a small, mighty Black population, which included carpenters, blacksmiths, bricklayers and successful farmers in the region where a vast majority of the state struggled.

But this all changed in 1912 when an 18-year-old white woman named Mae Crow was found beaten, bloodied and unconscious in the woods near Oscarville under mysterious circumstances, the events of which are documented in Patrick Phillips's book, Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America.

Crow later died from her injuries, and three young Black men — the only Black people in that part of the county at the time — were accused of raping and murdering her, with little evidence other than a coerced confession from one of them. Later, the three men were lynched, one publicly, in a nearby town square.

The people in this October 1912 newspaper photo are not identified but are believed to be, front row from left: Trussie (Jane) Daniel, Oscar Daniel, Tony Howell (defendant in another rape case involving a white woman), Ed Collins (witness), Isaiah Pirkle (witness for Howell) and Ernest Knox. (Atlanta Constitution)

Read more at Yahoo News: A lynching scarred this Georgia county. Is it willing to confront its dark past?

By the year’s end, all of Oscarville’s Black residents, as well as the greater Forsyth County’s 1,098 Black inhabitants — or 10% of the county’s population — were violently forced out, and their history was largely driven out with them.

“The case of Oscarville is complicated,” Dee Gillespie, a history professor at the University of North Georgia, told Yahoo News. “This particular Black community was not lost because of the lake. Instead, Black communities at Oscarville and throughout Forsyth County were lost much earlier because of mob violence.”

In 1956, what was left of Oscarville was submerged when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dammed the Chattahoochee River to create a lake for flood control and power generation for Atlanta and the surrounding counties, according to the Gwinnett County website. It was not initially intended for recreation.

The lake was named after Sidney Lanier, an 18th-century Georgia poet who wrote “Song of the Chattahoochee.” It cost about $45 million to complete, which included buying land and relocating families, businesses and cemeteries.

Buford Dam on Lake Lanier, May 10, 2013. (John Bazemore/AP)

But several structures remained, including unmarked graves, parts of an auto-racing track and concrete foundations of buildings. In recent decades when the water levels drop during a drought, tire parts and other relics have been exposed, which many believe contribute to the drownings. Though engineers say they removed anything they deemed as dangerous during their initial demolition, experts say forest areas with trees that are 60-feet tall and other objects like barbed-wire fences and old chicken coops that may have loosened over time can serve as debris for people to become entrapped in — but they’re hesitant to pinpoint one cause.

“Sadly, there are multiple factors that can cause a drowning in Lake Lanier,” Kimberlie Ledsinger, a spokesperson for the Hall County Fire Rescue, which recovered the body from the lake last week, told Yahoo News.

The volume of visitors alone is also not an adequate explanation for the deaths, as Lake Allatoona, located about 40 miles west of Lanier, has a similar number of visitors each year but one-third of the deaths, according to the Oxford American.

“There is also no way of truly knowing from our point of view as first responders what causes them,” Ledsinger said.

Read more at Yahoo News: ‘The issues at the lake need to be addressed’: Another man dies after swimming in ‘cursed’ Lake Lanier

Closed boat ramps at Lake Lanier's East Bank Park, Oct., 25, 2007.

In July, Tamika Foster, a fashion designer and the ex-wife of R&B singer Usher, started an online petition to "drain, clean and restore" Lake Lanier. Foster’s 11-year-old son was killed at the lake in the summer of 2012 after a boater struck him while he was floating in an inner tube.

“Lake Lanier has a dark and sordid past, marked by multiple tragic incidents that have resulted in the loss of innocent lives,” read the petition, which has been signed by more than 8,200 people.

Oscarville and Lake Lanier legacy

Much like the Greenwood community of Tulsa, Okla., who in the early 20th century had created Black Wall Street, which evolved into a thriving metropolis for Black Americans until white supremacist violence demolished it seemingly overnight, Oscarville, in its physical form, is a distant memory.

“The real haunting in this story is how history has made it impossible to ignore what was done to the land in North Georgia,” author and historian Lisa Russell, told CNN. “Once a land of wild rivers, North Georgia is now broken with dams and human-made bodies of water that changed the ecosystem. Once a land that [belonged] to indigenous people, it is now buried under the water, making recovering of lost culture impossible.”

Ku Klux Klan supporters in small town of Cumming, Ga., north of Atlanta, along a route of a civil rights march in 1987. Forsyth County had very few minorities living there at the time, and outspoken white supremacist sympathizers wanted to keep it that way. A series of civil rights demonstrations that year helped pave the way for more minorities to relocate into the county.

In Lake Lanier, the same playground for some thrill seekers is a painful reminder of the past for others. Even the murky waters that often form at the lake due to runoff from homes and farms and sewage discharge symbolize something more than its distinction as the state’s most polluted lake, which, at its worst, often emits an odd color and odor from the water caused by algae blooms.

It’s a story many believe epitomizes the lack of progress of the greater county as a whole.

“Until [local leaders] confront that history, there’s never going to be true diversity in Forsyth County,” Huddle said. “And it isn’t really about the physical population either. It’s about coming to grips with something that was really ugly.”