The agreement, said António Guterres, will "bring relief for developing countries on the edge of bankruptcy" and "help stabilize global food prices which were already at record levels even before the war."

United Nations (Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, Turkish Defense Minister Hulusi Akar, and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan attend a signature ceremony in Istanbul on July 22, 2022. (Photo: Ozan Kose/AFP via Getty Images)

JESSICA CORBETT

United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres on Friday celebrated an agreement by Russia and Ukraine to free up over 20 million tons of grain exports at blockaded Black Sea ports amid soaring food prices and fears of famine.

"Let there be no doubt—this is an agreement for the world."

Since Russia invaded Ukraine in late February, world leaders including Guterres have warned about the impact on the world's food chain. The Black Sea Grain Initiative was signed at a ceremony in Istanbul attended by the U.N. chief, Russian and Ukrainian ministers, and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Guterres thanked Turkey's leader for facilitating the negotiations that produced the agreement, and told the Russian and Ukrainian representatives that "you have overcome obstacles and put aside differences to pave the way for an initiative that will serve the common interests of all."

"Today, there is a beacon on the Black Sea. A beacon of hope, a beacon of possibility, a beacon of relief—in a world that needs it more than ever," he said. "And let there be no doubt—this is an agreement for the world."

"It will bring relief for developing countries on the edge of bankruptcy and the most vulnerable people on the edge of famine," Guterres continued. "And it will help stabilize global food prices which were already at record levels even before the war—a true nightmare for developing countries.

Related Content

Surging Prices Amid Ukraine War Have Pushed 71 Million People Worldwide Into Poverty

"The initiative we just signed opens a path for significant volumes of commercial food exports from three key Ukrainian ports in the Black Sea," he explained. The warring parties also reached an agreement to get Russian food and fertilier to global markets.

The New York Times reported on how the export operation will work:

Ukrainian captains will steer vessels packed with grain out of the ports of Odesa, Yuzhne and Chornomorsk.

Using passages that are not mined, they will pilot the ships to Turkish ports to be unloaded, and the grain will then be shipped to buyers around the world.

The returning vessels will be inspected by a team of Turkish, U.N., Ukrainian and Russian officials to ensure that they are empty, and not carrying weapons to Ukraine, a key Russian demand.

A joint command center with officials from all four parties will be set up immediately in Istanbul to monitor every movement of the flotillas.

The newspaper also noted that "no broad cease-fire has been negotiated, so the ships will be traveling through a war zone," and attacks at the ports or inspection issues could imperil the 120-day deal, which officials hope will be renewed on a rolling basis.

Guterres, in his speech Friday, also acknowledged that in Ukraine, "conflict continues. People are dying every day. Fighting is raging every day."

"The beacon of hope on the Black Sea is shining bright today, thanks to the collective efforts of so many," he added. "In these trying and turbulent times for the region and our globe, let that beacon guide the way towards easing human suffering and securing peace."

Leaders at humanitarian groups cautiously welcomed the agreement.

"The lifting of these blockades will go some way in easing the extreme hunger that over 18 million people in East Africa are facing, with three million already facing catastrophic hunger conditions," said Shashwat Saraf, the International Rescue Committee's East Africa emergency director.

"Let's be clear—this will not end or significantly alter the trajectory of the worsening global food crisis."

"The next and significant step must be fully funding the humanitarian response in the region, to stave off the worst impacts of the drought and prevent a catastrophic, unprecedented famine from fully engulfing the region by the end of the summer," Saraf added.

Tjada D'Oyen McKenna, CEO of Mercy Corps, said that if the deal is respected, it "will help ease grain shortages, but let's be clear—this will not end or significantly alter the trajectory of the worsening global food crisis."

"Unblocking Ukraine's ports will not reverse the damage war has wreaked on crops, agricultural land, and agricultural transit routes in the country; it will not significantly change the price or availability of fuel, fertilizer, and other staple goods that are now beyond the reach of many, particularly in lower-income countries; and it will certainly not help the majority of the 50 million people around the world inching closer to famine stave off starvation," she said.

Highlighting conditions from Afghanistan, Colombia, and Guatemala to Somalia, Syria, and Yemen, McKenna argued that "we must recognize that our global food systems were already failing and record numbers of people were edging toward poverty and hunger due to the economic pummeling of the Covid-19 crisis and the impacts of climate change."

Along with providing emergency assistance, she said, "urgent action must be taken to strengthen agricultural food systems: Scale climate-resilient agricultural production and boost support for local agriculture by providing smallholder farmers the information, financial, and regulatory support they need to help their communities and countries reduce reliance on imports."

Our work is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0). Feel free to republish and share widely.

Russia and Ukraine have signed a landmark deal with the United Nations and Turkey on resuming grain shipments in an attempt to ease a global food crisis in which millions face hunger.

Russian defence minister Sergei Shoigu and Ukrainian infrastructure minister Oleksandr Kubrakov each signed separate but identical agreements with UN and Turkish officials on reopening blocked Black Sea delivery routes.

Kyiv officials said they did not want to put their name on the same document as the Russians because of the five-month war that has killed thousands and displaced millions of Ukrainians.

Here is what you need to know:

What is the objective of the deal?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24 led to a de-facto blockade of the Black Sea, resulting in Ukraine’s exports dropping to one-sixth of their pre-war level. Both Kyiv and Moscow are among the largest exporters of grain in the world, and the blockade has caused grain prices to rise dramatically.

The deal aims to help avert famine by injecting more wheat, sunflower oil, fertiliser and other products into world markets, including for humanitarian needs. It targets the pre-war level of five million metric tonnes of grain exported each month.

The UN World Food Programme says some 47 million people are now in a stage of “acute hunger” due to fallout from the war and experts have long warned of a looming global food crisis if Ukrainian grain exports remained blocked.

Ukraine also needs to empty its silos ahead of a coming harvest, while more exported fertiliser will avoid lower global yields for coming harvests.

Russia and the UN also signed a memorandum of understanding committing the latter to facilitate unimpeded access to global markets for Russian fertiliser and other products.

© Provided by Al Jazeera

According to Russia’s Shoigu, grain exports could restart in the “next few days”.

“Today we have all the prerequisites and all the solutions for this process to begin in the next few days,” Shoigu said after signing the deal.

Al Jazeera’s Diplomatic Editor James Bays, reporting from the UN headquarters, said it could be a “couple of weeks” before the first shipment of grain leaves Ukraine.

“There will be a test of implementation in the coming weeks,” Bays said, noting the backlog of millions of tonnes of Ukrainian grain in the country. “It is going to take some time to get all of that grain out – experts estimate probably about four months,” he added.

The deal is valid for four months or 120 days and will be automatically renewed unless the war ends.

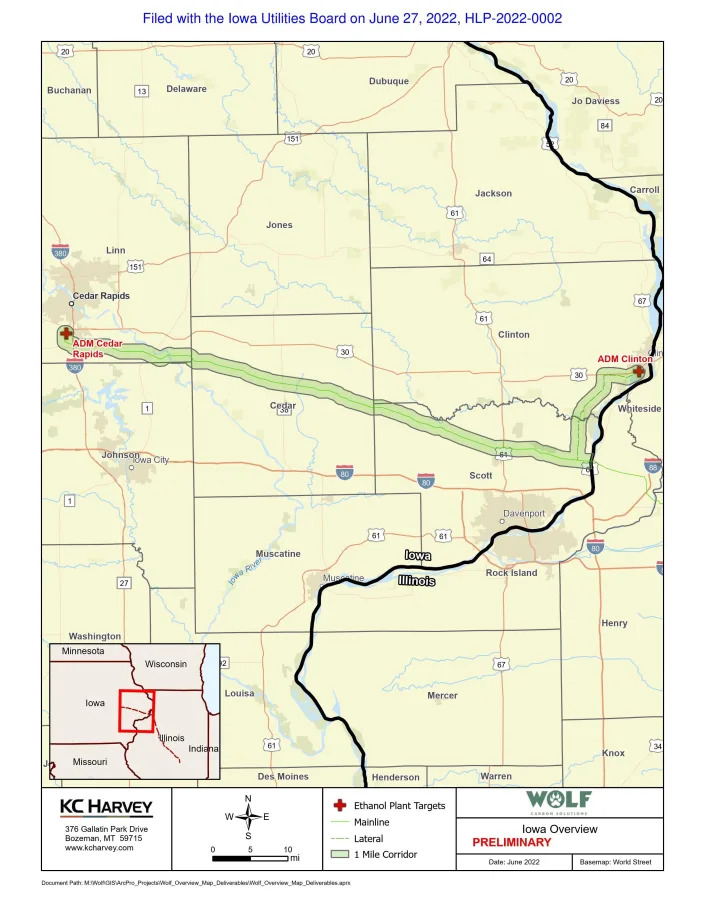

Which ports are included?

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said the accord would open the way to commercial food exports from three key Ukrainian ports – Odesa, Chernomorsk and Yuzhny.

A UN official told Reuters the deal included a “de facto ceasefire” for the ships and facilities covered.

A worker loads a truck with grain at a terminal during barley harvesting in Odesa

Guterres said there will be a Joint Control Center (JCC) in Istanbul, which will schedule and monitor shipments.

According to one UN official, the JCC will be staffed by officials from the UN and probably military officials from the three countries involved, Reuters reported.

Though Ukraine has mined the waters near the ports as part of its war defences, there is no further need for de-mining. Rather, Ukrainian pilots will guide the ships along safe channels in its territorial waters, with a minesweeper vessel on hand as needed but no military escorts.

Monitored by the JCC, the ships then transit the Black Sea to Turkey’s Bosphorus Strait and off to world markets.

All sides have agreed there will be no attacks on these entities. If a prohibited activity is observed, it will be the task of the JCC to “resolve” it, the official said without elaborating.

In response to Russian concerns about ships delivering weapons to Ukraine, all returning ships will be inspected at a Turkish port by a team with representatives from all parties and overseen by the JCC. The teams will board vessels and assess their cargo before they can return to Ukraine.

‘A beacon of hope’: How the world reacted

Russia

Defence minister Shoigu has said Moscow will not take advantage of the fact that the ports will be demined and opened. “We have made this commitment,” he said.

Ukraine

Foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba said Kyiv trusts the UN, not Russia, to uphold the deal.

“Ukraine doesn’t trust Russia. I don’t think anyone has reasons to trust Russia. We invest our trust in the United Nations as the driving force of this agreement,” Kuleba said at an online press briefing.

United Nations

Guterres said there was now a “beacon on the Black Sea” after the “unprecedented” agreement was finalised.

“A beacon of hope … possibility … and relief in a world that needs it more than ever,” he added.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said the pact will “renew hopes for peace”.

“With the ship traffic that will start in the coming days, we will open a new breathing tube from the Black Sea to many countries of the world,” he added after the deal signing.

EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell says the deal was a “critical step” in helping reduce global food insecurity.

“EU remains committed to help Ukraine bring as much of its grain into global markets as possible,” he wrote on Twitter.

United States

The US called on Russia to allow Ukrainian grain to be exported quickly and voiced hope that the Turkish-brokered deal was well-structured enough to monitor compliance.

“We fully expect the implementation of today’s arrangement to commence swiftly to prevent the world’s most vulnerable from sliding into deeper insecurity and malnutrition,” White House spokesman John Kirby told reporters.

Issued on: 22/07/2022

Text by: FRANCE 24

Ukraine and Russia are set to sign a deal in Istanbul on Friday to reopen Ukraine's Black Sea ports and release Ukrainian grain exports, according to Turkey. Here are some details of the measures likely to be adopted in the agreement.

Following nearly two months of tough negotiations, Ukrainian and Russian officials are expected to sign the Black Sea ports deal at a ceremony in Istanbul’s Dolmabahçe Palace in the presence of UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres.

Some of the measures negotiated by the two sides:

Control centre based in Istanbul

A coordination and monitoring centre will be established in Istanbul, to be staffed by UN, Turkish, Russian and Ukrainian officials, which would run and coordinate the grain exports, officials have said.

Ships would be inspected to ensure that they are carrying grains and fertiliser rather than weapons. It also makes provision for the safe passage of the ships.

The control centre will be responsible for establishing ship rotation schedules in the Black Sea. Around three to four weeks are still needed to finalise details to make it operational, according to the experts involved in the negotiations.

Inspections on departures and arrivals in Turkey

The inspection of ships carrying grain was a Russian condition to ensure vessels would not simultaneously deliver weapons to Ukraine.

These inspections will not take place at sea as was once envisaged due to practical reasons, but will be carried out in Turkey, probably in Istanbul, which has two major commercial ports at the entrance to the Bosphorus (Haydarpasa) and on the Sea of Marmara (Ambarli).

Conducted by representatives of the four parties, the inspections will done upon the departure and arrival of ships.

Securing shipping lanes

Russians and Ukrainians are committed to respecting shipping lanes free of military activity in the Black Sea.

Under the agreement, if demining is required, it will have to be carried out by a "third country". Details of the third party have not yet been specified.

From Ukraine, the ships will be escorted by Ukrainian vessels (probably military) leading the way out of Ukrainian territorial waters.

Four-month duration, automatic renewal

The agreement would be signed for four months and automatically renewed. If 20 to 25 tonnes of grain are currently outstanding in silos in Ukrainian ports, and at a rate of eight tonnes evacuated per month, this four-month period should be enough to clear the stocks.

A condition related to Russian grain and fertilisers

A memorandum of understanding must accompany this agreement, signed by the UN and Russia, guaranteeing that Western sanctions against Moscow will not affect Russian grain and fertilisers, directly or indirectly.

This was a Russian prerequisite for signing the agreement.