It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Sunday, May 29, 2022

Analysis by Andreas Kluth | Bloomberg

May 29, 2022

“When a stranger resides with you in your land, do not molest him,” a credible authority tells the Israelites in Leviticus. “You shall treat the stranger who resides with you no differently than the natives born among you; for you too were once strangers in the land of Egypt.”

The tension God was referring to is timeless. We all may one day need to flee from injustice, tyranny, violence, hunger or other calamities. And then we’ll need help. In turn, even if we’re lucky enough (for now) to live in stability, we should offer asylum to those fleeing to us. And yet we often don’t.

For the first time ever, more than 100 million people worldwide have been “forcibly displaced,” in the jargon of the UNHCR, the refugee agency of the United Nations. Millions of Ukrainian women and children have fled from Russia’s war of aggression in just the past three months. Millions more — often less conspicuous in the Western media — have run from violence in places like Ethiopia, Burkina Faso, Myanmar, Afghanistan or the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Both the numbers and the suffering are about to get worse. Also owing to the Russian attack on Ukraine — a “bread basket” that now can’t export its wheat and other staples — a global food crisis is imminent. Most people in Western countries will feel it as a painful rise in prices. But those who are already hungry — in Africa, the Middle East and elsewhere — will face starvation.

Margaritis Schinas, the European Union’s commissioner in charge of migration, told Bloomberg that he’s expecting another refugee crisis. In this one, people will be coming in dinghies across the Mediterranean, rather than on trains through Ukraine and Poland. It’ll be “more messy,” Schinas reckons. As if all those other crises hadn’t been messy enough.

I’ve never been a refugee, but as a journalist, I’ve occasionally witnessed the human toll of migration. I picked grapes in California’s Central Valley with undocumented farm workers from south of the border to hear their stories. They’re the heirs to the “Okies” who once fled America’s Dust Bowl, as described so hauntingly by John Steinbeck in “The Grapes of Wrath.” Except that they’re not only desperate and poor but also alien and unwelcome.

In 2015-16, I covered Europe’s refugee crisis. The migrants at that time were largely Syrians fleeing from their own murderous tyrant. I remember the range of reactions in Europe as they arrived.

At the train station in Munich, many Germans greeted the newcomers with bottled water, teddy bears and hugs. Other Germans were outraged about the chaos and wanted to keep the refugees out. Most were quietly apprehensive. A similar split in attitudes rent all of Europe. Countries such as Hungary turned the refugees back with barbed wire and water cannon.

This spread between hospitality (xenia in ancient Greek), xenophobia (literally, fear of strangers) and all the nuances in between has greeted aliens everywhere and at all times. It’s what God was talking about in Leviticus.

In my experience, the “xenophobes” are sometimes racist or callous but more often just anxious. In Germany in 2015, for example, the backlash against migrants was worst in what used to be the communist East, which has also become the bastion of the populist far right. In a meme I heard often, these Easterners felt that German reunification had turned them into second-class citizens in their own country.

Now they were watching exotic-looking foreigners arriving by the busload and — as they chose to interpret the situation — “skipping the line.” The aliens, in this narrative, were threatening to demote the Eastern Germans to third-class citizenship, and depriving them of nebulous rights — perhaps welfare, attention or compassion — that should belong only to the native-born.

The Scotch-Irish in 19th-century America probably felt the same way when the German immigrants arrived, until the Germans said all this about the Irish, who then repeated it with the Italians, then in succession, the Russians, the Jews, the Chinese… So it goes.

Part of human nature is to distinguish between in-groups and out-groups, and to show the ins more empathy than the outs. Even Benjamin Franklin, ordinarily an open-minded type, looked askance at German and other non-English immigrants, whom he considered “swarthy” and suspect.

That might explain the about-turn in Polish policies and attitudes between the 2015 crisis and this year’s. Back then, the refugees were dark-skinned Muslims, and Warsaw slammed its borders shut. Now they’re fellow Christians and Slavs, and Poland has warmly welcomed more than half of the 6.7 million Ukrainians who’ve fled abroad.

So there we are, forever stretched between dueling human impulses: on one side, openness, compassion and altruism; on the other, suspicion, prejudice and nativism. Some of us emphasize optimistic stories of migrants integrating well into their adopted societies, playing by the rules and just rebuilding their lives. Others dwell on those other tales — of traumatized refugees becoming a burden to their host country or committing crimes.

All these stories exist, and all are equally worth hearing. Then again, the exact same range of biographies exists for the native-born as for migrants. Ultimately, they’re just a reminder that we’re all — aliens and natives alike — human, as Leviticus understood.

The biggest refugee crisis in history is still ahead of us. War, famine and plague will not only stay around, but spread and become worse, because of climate change. What will that do to our societies, and to us as individuals?

All of us, since our common ancestors trudged out of the East African rift valley, descend from migrants. If we go back far enough, we all have refugees among our forebears. And all of us, if we’re not already displaced, can be sure to have descendants who will flee from something. We all were, are or will be natives and aliens somewhere, at some time.

There are no easy answers. Speaking for most Germans in 2015, the country’s president at the time, Joachim Gauck, expressed the dilemma well: “We want to help. We are big-hearted. But our means are finite.” It’ll be important to keep both parts of that sentiment in mind — the magnanimity and the limits. But when in doubt, we should heed Leviticus, and keep our hearts big.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andreas Kluth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European politics. A former editor in chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for the Economist, he is author of “Hannibal and Me.”

Saturday, May 21, 2022

A wealthy American wanted to build an island republic. The king of Tonga had other ideas.

BY RAYMOND CRAIB

SLATE

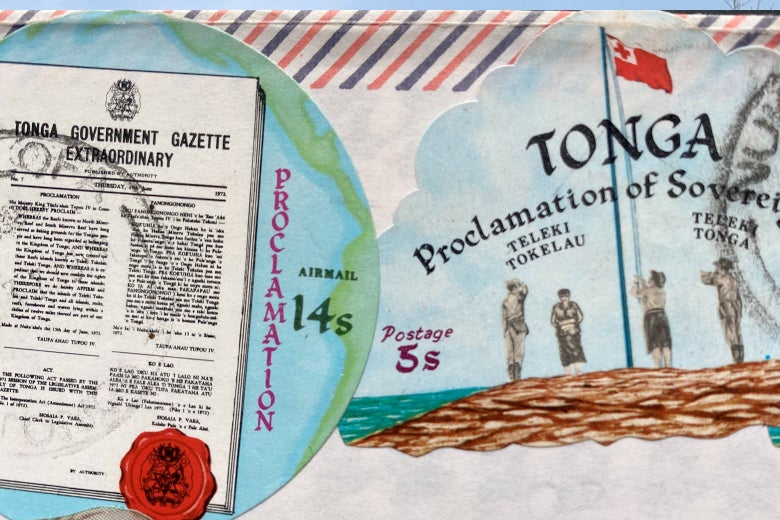

Once upon a time, a wealthy man set out to establish his own country. He found a shallow reef over which the waters of a vast ocean had lapped since time immemorial. He hired a company to dredge the ocean floor and deposit the sand on the reef. An island would be born, upon which the man had a concrete platform built, a flag planted, and the birth of the Republic of Minerva declared. The monarch of a nearby island kingdom was not impressed. He opened the doors of his kingdom’s one jail and assembled a small army of prisoners. The monarch, his convicts, and a four-piece brass band boarded the royal yacht and descended upon the reef, where they promptly removed the flag, destroyed the platform, and deposed, in absentia, the man who would be king. And Minerva returned to the ocean

The story of Michael Oliver, his short-lived 1972 Republic of Minerva, and the response of the king of Tonga is not the stuff of fairy tales. Nor is it an uncommon story, an isolated event ripe for consumption as a chronicle of crazy rich Caucasians. In the U.S. after World War II, with the dramatic geopolitical changes wrought by decolonization and the Cold War, battles were waged over the meaning of ideals such as democracy and freedom, often pitting those who believed individual liberty to be more important than social equality against those who prioritized the latter over the former. In the midst of such struggles, individuals concerned with protecting their wealth, their safety, and their freedom from what they perceived to be an overbearing government and a threatening rabble sought to exit the U.S. and to establish their own independent, sovereign, and private countries on the ocean and in island spaces. It usually did not end well.

Experiments in libertarian exit—abandoning one’s country of residence for a private territory where social relationships are structured largely through contract and exchange—like the one Michael Oliver undertook were not unusual in the America of the 1960s and 1970s. They proved common enough that writers for the Los Angeles–based libertarian Innovator Magazine priced out the costs of various forms of exit, from “clandestine urban” and “underground shelter” to “sea-mobile nomad.” It was only a small step to imagine a commune on the high seas rather than in Northern California, or a private island in the Caribbean rather than a gated community in Orange County. Libertarian-inspired exit projects proliferated to the degree that one might recast the 1960s not as the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, but as the Age of Atlantis, the favored island reference point for libertarians.

The name itself was ubiquitous. The “Republic of New Atlantis” arose, albeit briefly, in 1964 when Ernest Hemingway’s younger brother Leicester parked an 8-by-30-foot bamboo raft, anchored to an old Ford engine block buried in the sand, 8 miles off the coast of Bluefields, Jamaica. He declared the birth of his new republic with a bottle of Seagram’s 7 in hand. Having encouraged birds to defecate on one end of the raft, he ceded that portion of it to the U.S. under the criteria established in the 1856 Guano Islands Act, which allowed citizens to claim possession of unoccupied islands, rocks, or keys that contained guano on behalf of the U.S. The raft’s other half became his own private country, albeit only briefly; a hurricane soon sank the vessel. Pharmaceutical engineer Werner Stiefel, whose family had fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s, founded “Operation Atlantis” in 1968 in a motel next to I-87 in upstate New York. He recruited libertarian “immigrants” to collectively build a vessel that they would sail down the Hudson River to the Caribbean where they would establish a libertarian micronation. Like its namesake, it met a watery fate. Upon launch on the Hudson, the vessel capsized and caught fire. The Atlanteans, undeterred, repaired the ship and sailed it to the Bahamas, where it promptly sank during heavy weather.

A kind of iconoclastic curiosity could underpin some of these schemes, but it was more frequently unease and fear that drove exit projects. Apocalyptic scenarios of demographic, ecological, and monetary collapse proliferated in the 1960s, along with fears of nuclear annihilation. Works such as Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb and Garrett Hardin’s “The Tragedy of the Commons” were only the most prominent of a corpus of works that warned of an approaching disaster due to unchecked population growth and ostensibly unmanaged resources. Harry Harrison’s novel Make Room! Make Room! was reworked into the 1973 film Soylent Green, starring Charlton Heston as New York City detective Robert Thorn who, in the year 2022, discovers that the Soylent Corporation’s protein pills, allegedly created from ocean plankton, are made of human corpses. Ayn Rand and libertarian fellow travelers forecast monetary collapse due to government meddling, and encouraged listeners to instead invest in gold, a libertarian prediction and prescription that is now so often reused as to seem like parody. But just as prominent in the minds of exiters such as Michael Oliver as these apocalyptic concerns was a fear of social unrest and totalitarianism.

Born Moses Olitzky in Kaunas, Lithuania, in 1928, Oliver had survived German massacres of Jews in his hometown, and then the Stutthof and Lager 10 concentration camps. Rescued by U.S. troops in 1945 while on a forced march from Dachau, he spent two years in a displaced persons camp before emigrating to the United States in 1947. His parents and four siblings all had been murdered. Once in the U.S., Olitzky changed his name to Michael Oliver and set roots down in Carson City, Nevada. He owned and operated a land development company as well as the Nevada Coin Exchange, specializing in the sale of gold and silver coins, which he advertised as security investments in the pages of the Wall Street Journal, Barron’s, and Innovator.

Over the course of the 1960s, Oliver became quite wealthy and began to translate that wealth into a hedge against a perceived rise of totalitarianism in the U.S., which he discerned in riots and protests around the country. Although he railed against “social meddlers” who opposed the free enterprise system and criticized how the government robbed society’s producers by creating welfare programs or pursuing inflationary policies and deficit spending, it was the masses and their supposed susceptibility to demagoguery that most concerned him. While he could have identified the populist, often apocalyptic and violent, politics of the right—the John Birchers and the Minutemen, the Ku Klux Klan and the Christian anti-Communist crusaders—as the existential threat, it was populations acting in the name of “liberalism” and “freedom now” whom he accused of employing “Storm Trooper tactics.” His libertarianism dovetailed with the socially conservative property-rights movement that took shape around Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential candidacy, and has grown ever more potent in recent decades.

Oliver ignored calls to stay put and fight for liberty at home. Instead, he sought to escape what he saw as the approaching storm of social unrest and revolution by creating a new country. Its structure he outlined in a self-published 1968 book, A New Constitution for a New Country. Oliver crafted his constitution for an imagined libertarian territory freed from bureaucratic constraints and the regulatory apparatus of the welfare state. The book contained a declaration of purpose, a plan of action, and a constitution with 11 articles. Oliver designed the constitution as an improved version of the United States Constitution—improved in that it would “spell out the details whereby government can, at the same time, properly protect persons from force and fraud and also be prevented from exceeding this only legitimate function.” The argument that the sole function of government is to protect individuals from force and fraud echoed mainstream libertarian thinking of the time, found in the work of novelist Ayn Rand, economists Milton Friedman and Ludwig von Mises, and philosopher Robert Nozick. Although its proponents describe the ideal government as a “nightwatchman” or “ultra-minimalist” state, it would be a mistake to understand this as a call for a smaller state. Its minimalism had little to do with the size of its apparatus or budget, but rather with the limitations placed on the range of its functions: national defense, policing, and a legal infrastructure dedicated to the protection of property rights and enforcement of contract.

Published in February of 1968, Oliver’s book sold out quickly, and a second edition appeared in May of that same year. Admiring readers found the book via word of mouth and advertisements in libertarian magazines and soon convinced others of Oliver’s vision. Among these acolytes were Wichita wheat magnate and World Homes chief executive Willard Garvey, millionaire horologist Seth Atwood, famed banker and fund manager John Templeton, and former placekicker for the undefeated 1954 Ohio State football team (and inventor of the eponymous WEED tennis racquet) Tad Weed. They helped bankroll efforts to put Oliver’s new country idea into action through his Ocean Life Research Foundation.

The foundation’s name is revealing. In order to build a self-governing, private territory in which the very promises of libertarian theory could be fulfilled, Oliver required a locale not already under the sovereign control of another state, or that a state would be willing to sell for such purposes. In the high era of decolonization—between 1945 and 1960 alone, the number of nation-states represented in the United Nations doubled, and over the course of the 1960s grew further due to decolonization in Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific—Oliver seemed assured that he could find a government with which to negotiate. “A surprising number of nearly uninhabited, yet quite suitable places for establishing a new country still exist,” he informed readers of his Capitalist Country Newsletter in 1968. “Many such places are scarcely developed colonies whose governmental or other activities are of little or no concern at all to their ‘mother’ countries. There will be little problem in purchasing the land, or in having the opportunity to conduct affairs on a free enterprise basis from the very beginning.”

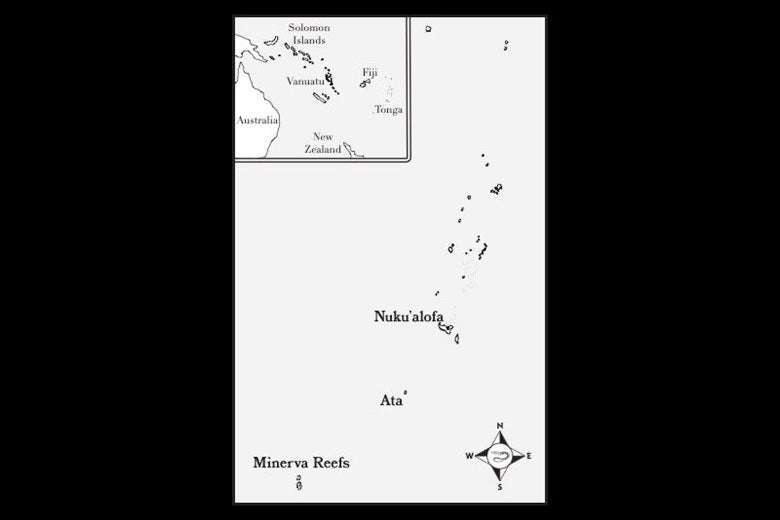

This was an optimistic evaluation, as Oliver would repeatedly learn in the coming decade. Between 1968 and 1971 alone, he or his associates made exploratory visits to the Bahamas, Turks and Caicos, Curaçao, Suriname, New Caledonia, French Guiana, Honduras, and New Hebrides to gather information on climate, taxation, and land quality and to explore the possibilities of building a libertarian country. Such visits revealed the difficulties confronting any would-be world builder looking to land on distant shores. Purchasing land was no problem. But purchasing sovereignty was. And so his first real effort unfolded on a space long seen as open: the ocean.

“There will be little problem in purchasing the land, or in having the opportunity to conduct affairs on a free enterprise basis from the very beginning.”— Michael Oliver, founder of the Republic of Minerva

That oceans and islands have figured prominently in exit efforts should come as no surprise. Both have long constituted spaces upon which to situate arguments and plot fantasies about the market, exchange, politics, and society. It was under the ocean (not upon it) that Captain Nemo, antihero of Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, sought to escape the tyranny of nation-states. On the ocean proved as appealing as under it. In one of his less well-known works, The Self-Propelled Island, Verne described the geography of the island Pacific by using as his primary narrative device a large, artificial floating island inhabited solely by bickering billionaires—a prescient vision of 21st century seasteading. The high seas were and are still frequently invoked, even if mistakenly, as spaces of nonsovereignty and lawlessness, the last great frontier for those seeking freedom from the state, whether it be to profit through illegal fishing and exploitation of labor or to experiment with new forms of political and social life.

Similarly, “remote” and small islands have provided a place for imaginative experiments in political, legal, and social engineering, from Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis and Thomas More’s Utopia to H.G. Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau and William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. As clearly defined, circumscribed territorial entities, small islands can seem like natural laboratories in which political and social experiments can unfold without the noise of contingency, the burden of history, or the taint of politics. Given that one of classical liberalism’s founding myths, Robinson Crusoe, grew out of the fertile soil of a distant archipelago, it is not surprising how much islands figure in libertarian exit fantasies. Alexander Selkirk’s four-and-a-half-year struggle as a castaway isolated on the Juan Fernández Islands off the coast of Chile served as the historical basis for Daniel Defoe’s novel, a story that made remote islands an ideal libertarian political ecology: an overdetermined geographic form upon which the drama of individualism, of man alone, could be staged.

Islands and ocean spaces have been attractive not only because they are conceived of as laboratory spaces but also because they are very often sites that seem ripe for speculation and planning for new countries. In the post–World War II world, many island territories were the last to decolonize. Much of the Pacific remained under colonial control into the 1970s, and a significant portion still exists somewhere between dependence and independence. Such political opacity and geopolitical vulnerability made them attractive locations for those looking to get some territorial purchase on their libertarian dreams.

By 1971, Garvey, Atwood, Oliver, and their associates had set their sights on the Minerva Reefs. They did so after having rejected the option of another southwest Pacific atoll, the Conway Reef, when they learned that an Australian consortium intended to develop it for the construction of a casino. The Minerva Reefs were more attractive. They seemed to sit within neither the territorial waters of Aotearoa New Zealand to the south, nor Fiji or Tonga to the north. In August 1971, the Ocean Life Research Foundation arrived at the Minerva Reefs and began the arduous process of building an island in the southwest Pacific. A dredging vessel piled sand on the reef, while a small crew erected two mounds made from coral wrapped in chicken wire and encased in concrete, upon which they then constructed 26-foot vertical markers topped by a flag representing the Republic of Minerva.

These steps laid the groundwork for the new country, which would operate as an offshore financial center and house 30,000 settlers. Funds for the country came from settlers who would pay a base rate for a 3-acre plot of land, and from investors who, rather than settle in Minerva, would back the project and share in the profits. A corporation and board of directors would steer the process and review every settler application. “Capability of self-support,” Oliver wrote, “or sufficient assets shall be one of the requirements for acceptance.” Other conditions also applied: “collectivists […] criminals, nihilists, or anarchists” would not be welcome, regardless of their purchasing power.

Anarchists and nihilists turned out to be the least of their worries.

Anarchists and nihilists turned out to be the least of their worries.

One incident in particular tied Tonga and the reefs together. In 1962, the Tuaikaepau, a 50-foot, 20-ton cutter bound for Aotearoa New Zealand from Tonga, struck the northwestern edge of South Minerva Reef. Capt. Tevita Fifita, the crew, and the passengers—all Tongan and all of whom survived the initial impact and a night struggling with the thunderous high tide—knew they were in serious trouble. Far from shipping lanes and subject to the cold winds that blew north from Antarctica across the Tasman Sea, the Minerva Reefs saw visitors infrequently. For three months the group struggled, holed up in the shell of a rusting Japanese fishing vessel that had foundered on the reefs two years earlier. They survived on fish, crayfish, and the small amounts of water they could either produce with a homemade still or catch from infrequent rains. Most of them suffered from various ailments, and in early October, in the span of only two days, three men died. The men buried the body of the first person to die in the reef. They wrapped his body in layers of canvas to protect it from crabs and fish. They marked the grave with a cross. Soon after, Fifita made the decision to build an outrigger canoe from the remains of available wreckage, and, along with his son and the ship’s carpenter, they paddled to Kadavu, Fiji, where their vessel capsized while attempting to navigate the reefs. Fifita’s son drowned. The remainder of the rescue party succeeded in reaching help.

Tongans mourned the tragedy and celebrated the rescue. Queen Sālote declared a national holiday and wrote a poem in the crew’s honor. The Minerva Reefs became indelibly attached to the memory of Tuaikaepau and the history of its crew and passengers. In 1966, Fifita returned to the reefs and attached a Tongan flag to a buoy there, an act that took on the important appearance of a ceremony of annexation. Then, in 1972, conflict with the Ocean Life Research Foundation erupted. As word of the exiters’ activities spread, King Tupou began investigating. In February 1972, he sent a fact-finding mission to the reefs. The participants established a refuge station on the South Minerva Reef, but the king’s government made no immediate claim of possession or sovereignty. In May, he himself sailed to the reefs with the brass band and freed convicts accompanying him. He ordered the building of a structure on each reef that would remain permanently above the high-water mark. The king then used these built structures as the basis for a claim of possession on June 15, 1972.

The king’s assertion of sovereignty had the potential to stoke conflicts, particularly with neighboring Fiji, but at the intergovernmental 1972 South Pacific Forum meeting, convened for Southwest Pacific trade discussions and cooperation, heads of state from Fiji, Nauru, Western Samoa, and the Cook Islands agreed that Tonga had a long-standing historical association with the reefs, and that any other claim to sovereignty, and in particular “that of the Ocean Life Research Foundation,” was unacceptable. The king could count on regional support from other heads of state because they, too, feared that any successful libertarian colonization would open up dozens of Southwestern Pacific seamounts and atolls to claims of ownership. The question reached well beyond the bounds of one nation. As Oceanian decolonization proceeded, questions of archipelagic territorial rights to the ocean—never adequately addressed in early U.N. conferences on the sea—arose and led to the writing over the course of the 1970s of a series of Archipelagic Provisions that would be adopted at the 1982 Conference on the Law of the Sea. Such provisions accentuated what islanders themselves had long understood: that the ocean was a human space.

Oliver and his backers withdrew. For the founders of the Republic of Minerva, the reefs were a space of legal liminality, one of the few areas where establishing a new country seemed possible. With terra firma firmly divided among nation-states, the oceans seemed to be the only empty spaces left. Yet, as has so often been the case, spaces perceived by distant colonizers as open for the taking are in fact places that sit within the social and cultural horizon of nearby peoples. For Tongans, the reefs were part of a history of navigation and settlement, of rescue and loss, of meaning and mourning, and part of a geography of identity and livelihood where sea and land entwined. Rather than distant atolls, they were places of provision and poetry and history. No doubt one day, maybe a thousand years hence, a natural island will come to be in Minerva, a result of processes of the kind that had built up the reefs themselves. But not until then. The only invisible hand at work among the atolls and seamounts of the Native Pacific will be that of the ocean.

Adventure Capitalism: A History of Libertarian Exit, From the Era of Decolonization to the Digital Age

By Raymond B. Craib. PM Press.

Friday, May 20, 2022

The Canadian Press

CALGARY — The stakes are high as Canadian farmers take to the fields to plant 2022's crop, which some are saying could find a place in the record books as "the most expensive ever."

On her family's farm northeast of Calgary near Acme, Alta., where she farms with her husband Matt, Tara Sawyer already knows she's going to need a better-than-average crop this year just to break even.

All of her input costs have surged since last year due to inflationary pressures, spiking energy costs, and the war in Ukraine. The price of fertilizer is more than double what it was last year, and the diesel used to power her farm equipment also costs nearly twice what it did last year at this time.

But getting that above average crop could be a challenge. Last year, Sawyer's farm was hit hard by the widespread drought that reduced crop yields across Western Canada and there are fears already that this could be another dry year.

"Most farmers, including us, saw a 30 per cent reduction in our yields, so we need to be able to have really good yields come out this year in order to pay for that," she said. "But in our region, we're already horribly dry, so we're concerned."

But it's not all bad news. While the cost of everything from seed to herbicides to tractor tires has increased in 2022, so too have crop prices. Sawyer, for example, grows wheat, barley and canola — all of which are hot commodities right now due to supply pressures created by the Russia-Ukraine war and the aftermath of last year's drought.

“There’s a number of crops that are sitting at all-time highs, or near all-time highs," said Jon Driedger, of Manitoba-based LeftField Commodity Research. "If you go back two years, the price of canola has doubled, almost tripled. Wheat's higher than it's been in 20 years, corn's pushing up against a record high. It's really across the board."

In fact, Driedger said crop prices are high enough that any farmer able to produce a "normal-sized" yield should still be able to earn a sizable profit. But in addition to the dry conditions in Alberta, many farmers in Manitoba and eastern Saskatchewan have the opposite problem and haven't even been able to get onto the land yet due to flooding and excess moisture.

The acres seeded by Canadian farmers this spring will not only be the most expensive in history, but in some ways, the riskiest as well, Driedger said.

“For those farms that are fortunate enough to harvest a normal crop or even better, it could be a great year. But there’ll be a lot of farms for whom that’s looking awfully precarious right now.”

Cornie Thiessen — general manager of ADAMA Canada, a Winnipeg-based company that sells crop protection products like fungicides, herbicides and insecticides — said some of these inputs have become significantly more expensive and harder to find due to supply-side factors like COVID-driven disruptions at manufacturing plants and shipping delays. But he added the war in Ukraine is also increasing demand for these products, as farmers get the message that this year, their work is more vital than ever.

“Very high crop prices change the economics for farmers of how much they invest to protect the crop," Thiessen said. "With really high prices like we're seeing right now, it sends a message to farmers that the world really needs your crop so you need to make it as big as possible. You need to spend more on fertilizer and herbicides to maximize those yields."

Thiessen said 2022 will likely be the most expensive crop ever planted in Canada, and there's a lot riding on it.

"For the individual farmer, certainly there is an opportunity to take advantage of these high prices, but it's a bigger investment than before," he said. "If the weather works against them and they have a poor crop, that's where the downside risk comes in."

"And for the world, to help alleviate concerns about food security, we really do need Canada to produce a great crop this year," Thiessen added. "If Canada's crop isn't as strong as possible this year, it will further exacerbate concerns about food security."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published May 20, 2022.

Amanda Stephenson, The Canadian Press

From rain to snow to nothing at all, Saskatchewan weather is leaving many farmers wondering if they will be able to seed at all this season.

© Global News

Global News

It truly is a tale of two worlds. East Saskatchewan has too much moisture in its soil while the west is hoping to get even one rainy day. It's a challenge farmer Clinton Monchuk understands firsthand having farmland near the Lanigan area.

"We've probably had a little over three inches of rain since the beginning of May," Monchuk said. "So it is a little bit wetter and we're just having a little bit more of a tough time getting seeding done."

Read more:

It's a reality faced by farmers across the province. On average, more than half of the seeding process is complete by this time. But, this year it's a different story.

Ian Boxall, president of the Agriculture Producers Association of Saskatchewan. has farmland near Tisdale.

"It's raining here today and it snowed this morning," Boxall said. "We're way far behind. Normally we would start seeding on May 1 and now I haven't started and it's the 19th of May so we are behind.

"I am not panicking yet but if it doesn't straighten up soon, I am going to start to panic."

According to Boxall, the seeding deadline is June 20. He says for producers in the west of the province with no moisture to be found on their land, it's a deadline they may not meet.

"Once it warms up we'll have a good crop started and out of the ground," said Boxall. "But those guys in the west, they really need rain to get that germinated and get that crop going over there so my concern is with them."

But seeding is not farmers' only concern. For Monchuk, it's the cost to farm. With inflation continuing to rise it's becoming more and more expensive to get their products out to the public.

Read more:

‘Very stressful’: Cold weather delays crops for many B.C. farmers, but no relief in sight

"We know as we move forward food inflation is going to get higher," said Monchuk. "We are seeing some of those shortages so this is some of the reasons, some of the extra cost that we have now. It does filter down and will result in higher prices of food as we move forward."

Video: Sticker Shock: Navigating the increasing food costs

Jake Edmiston - Yesterday

Financial Post

© Provided by Financial PostAfter a tough year in Canadian agriculture, CN Rail believes farmers will see a better crop this year.

Canada’s largest railroad is bracing for a surge in grain shipments across the country this year — a sign of hope that this year’s harvest will be better than the last one, when extreme drought devastated crops across the Prairies.

“Every kernel that’s harvested this year is going to want to move,” Canadian National Railway Co.’s new CEO Tracy Robinson told the Bank of America’s transportation conference on May 17. “We need to be ready for that.”

After a tough year in Canadian agriculture, CN believes things are starting to look up, judging from soil moisture levels this spring that suggest a more normal grain crop is coming.

“It would be a good thing for the world, wouldn’t it?” Robinson said. “A lot has to happen right from here. But I think we’re starting out in a positive way.”

The shot of optimism comes as the world faces a food crisis driven in large part by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The conflict has destabilized one of the most important regions in the world for grain exports, causing major spikes in commodity prices that have contributed to a troubling burst of inflation. Prices are likely to stay high for months due to global supply issues, the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization warned last week.

© Dave BishopA farmer plants durum wheat in a field on his farm by Barons, Alta.

And no matter how good Canada’s crop turns out to be, it won’t be enough to alleviate those issues on its own. The country’s agricultural output — even with a bumper crop — isn’t large enough to make a major impact on global supply, according to Ted Bilyea, a former executive at Maple Leaf Foods Inc. who is now a distinguished fellow at the Canadian Agri-food Policy Institute.

“I don’t think I see it moving the needle much,” Bilyea said. “We need a good crop just to keep things going where they are. … We’ve got to hope that the rest of the world has a good crop.”

Richard Grey, an agricultural economist at the University of Saskatchewan who helps his son run a family farm in Indian Head, Sask., was checking prices for canola on May 18. He could lock in a contract at about $24 a bushel, to be harvested and delivered to a shipper in November.

“That’s double what it was last year,” Grey said, adding that higher gasoline prices are driving up demand for ethanol and biofuel, which in turn drives up prices for grain and oilseeds, such as canola. “This is all to do with the international situation.”

Statistics Canada reported May 18 that food inflation is accelerating at a pace not seen since 1981. The consumer price index found grocery bills in April shot up 9.7 per cent compared to last year, with bread up 12.2 per cent, cereal up 15 per cent, pasta up 19.6 per cent, and cooking oil up 28.6 per cent.

“High inflation is here to stay in 2022,” Bank of Nova Scotia analyst Patricia Baker wrote in a note to investors. “Supply constraints and geopolitical conflict are expected to impact the energy, agriculture, and commodity markets.”

While Canada’s crop is expected to be better than last year, it’s not guaranteed to be good. In the middle of the spring planting season, farmers in Manitoba and southeastern Saskatchewan are facing fields so wet that they’re struggling to get seed in the ground. In southern Alberta, however, it’s too dry.

“Those that are saying we’re poised to have at least an average crop wouldn’t be out of line,” said Tom Steve, general manager with the Alberta Wheat and Barley Commissions. “To say that it’s going to be what we call a bumper crop, that’s pretty early to be saying that.”

CN’s chief executive agreed. “Now listen, I come from a farm in Saskatchewan,” she told the Bank of America conference. “And my father likes to say to me, `You’d like to get really excited about the grain crop, but so far we’ve never harvested one before we’ve seeded it.'”

Still, CN is preparing for an “inevitable surge” in grain shipments in the latter part of the year, investing in high-capacity hopper cars that can carry 10 per cent more grain, Robinson said. The railway confirmed it has added 3,000 hopper cars since 2019, with another 1,250 expected between 2023 and 2024.

“Getting this running is not just about the railroad getting ready,” Robinson said. “We need our partners, the terminals, and we need our customer facilities to be (ready) … We’re optimistic, for all of our sake, that this happens.”

“Their performance has been absolutely abysmal this past crop year,” said Steve at the Alberta Wheat and Barley Commissions. “It was just horrible. They couldn’t move the crop that we had. So they’re telling their investors and shareholders that they’re going to do better? We’ll believe it when we see it.”

• Email: jedmiston@nationalpost.com | Twitter: jakeedmiston

Growing discontent has led to a united national opposition against President Kais Saied. But could the pursuit of democracy backfire — and see the nation return to an iron fist rule?

While around 2,000 protesters is not yet anywhere near the Arab Spring demonstrations, it's a strong symbol

After 10 months of authoritarian rule by Tunisia's President Kais Saied following a power grab, many in the crisis-ridden country are united in pushing for a return to democracy.

Around 2,000 people of different political affiliations took to the streets on Sunday following a call by the newly-formed alliance National Salvation Front.

While the turnout was not comparable to the massive sit-ins in 2013 when thousands of people called for democratic elections, the meaning is nevertheless significant: A growing number of people, political parties and factions are joining forces to reject the political course on Saied's watch.

Who is the opposition?

One of the key players of this new alliance is the Islamist party Ennahda, one of Saied's fiercest opponents.

"Ennahda has become part of a civil political resistance that will use all civil and peaceful means to overthrow the coup and to push for the national dialogue that the country needs," Imed Khemiri, spokesman of the Ennahda party, told DW.

For him, this means, above all, dialogue between political parties. "The president does not want a dialogue except with himself," he said.

Another major player is a group of civil activists called Citizens Against the Coup.

"Since we began our struggle 10 months ago, we were able to convince many people that what happened was a coup, which symbolizes a great gain for collective awareness," Ezzeddine Hasgui, a political activist and founding member of the movement, told DW.

What prompted the protests?

In July last year, Kais Saied, a former law professor, had suspended the country's parliament, dismissed the prime minister, and issued an emergency decree, by which he has been ruling ever since.

Saied, however, insists that his political moves are democratic and have been necessary to guide the country to a new constitution, through a referendum in July 2022.

Yet, critics doubt the referendum will take place, as preparations are stalling.

The country has been sliding from one crisis into the next. Amid the political crisis, growing domestic debt, as well as rising inflation and increasing unemployment rates, the situation has been exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. The conflict in Eastern Europe saw a shortfall of up to 60% of wheat imports in Tunisia — severely impacting food security in Tunisia.

Moreover, the initial wave of public support Saied rode due to his promises to clamp down on corruption, has been fading.

Until this week, the Tunisians had not united in calling for a return to democracy.

Tunisia, which imports up to 60% of its wheat, will suffer from grain shortages due to the war in Ukraine

More voices speak up

While Sunday's turnout is seen by some as a disappointment, the organizers argue that the opposition is gaining momentum.

They're also gaining influential voices.

"Ahmed Neijb Chebbi, a leftist progressive and long-time opposition figure, has come forward with his Al-Amel Party (Hope) to call for the National Salvation Front," Alyssa Miller, a researcher who is based in Tunis for the German think tank GIGA Hamburg, told DW.

For her, Chebbi is worth watching, as "he could position himself as an important unifying force to broaden the opposition beyond Ennahda and pro-Ennahda forces."

The Ennahda party has been discredited by large portions of the population, as it has been blamed for corruption and political infighting in parliament prior to its dissolution on July 25 last year.

"In order to be successful, the anti-July 25 opposition must appeal to a broader base of political parties and civil society forces," Miller said

Therefore, she considers the latest statements by the country's influential union, the Tunisian General Labor Union (UGTT), as significant.

"In the past, the UGTT has been largely neutral or cautiously supportive of Kais Saied, and it was recently tapped by the president, along with the Tunisian League for Human Rights, to oversee the composition of a constituent assembly and to write a new constitution which would be put to a national referendum on July 25th," Miller said.

However, the two organizations have signaled they would not support Saied's process "unless it were inclusive," she added.

The inclusion of opposition voices, though, has been opposed by Saied.

It's unclear whether oppositional unity will evolve into a widespread movement, but the situation has similarities to the calls for democracy in 2013.

Back then, however, the overall situation was much closer to violent clashes than it is today.

And yet, just like this time, the Tunisian Confederation of Industry, Trade and Handicrafts (UTICA), the Tunisian Human Rights League and the Tunisian Order of Lawyers were asked to be on board of a new constitutional committee — along with the UGTT.

In turn, those four groups became famous as 'The National Dialogue Quartet' . It is widely believed that they averted a civil war, and their efforts were awarded with the Nobel Peace Prize in 2015.

Despite this similarity, the country's security situation was much worse.

"Along with the assassinations of the two popular leftist politicians, Chokri Belaid and Mohammed Brahmi, the country experienced a general rise in violence committed by Islamist insurgent groups in 2013," Miller explains.

Therefore, she doubts that tensions will rise to this extent again. "If we compare the situation with Tunisia today, we can see that the security situation is very, very different," adding that many of the violent insurgent groups that operated in northwestern Tunisia in 2013 have been "slowly brought under control under subsequent governments."

But she does see — yet again — some administrative powers meant to assist in the fight against terrorism are being used to target political opponents.

For Miller, this could indicate a return to an iron fist rule. "I think it is more likely that there is a return of authoritarian control of the type that was practiced and exercised in Tunisia under Ben Ali," she said.

Edited by: Stephanie Burnett

Sunday, May 15, 2022

PRISON NATION USA

Decriminalized Marijuana Reinvents Racism and Poisoning

by Don Fitz and Susan Armstrong / May 14th, 2022

The change in marijuana laws across the US raises issues far beyond, “Hey, dude, we can blow a joint now without getting busted.” The racism that permeated the age of criminalization now lurks throughout the phase of decriminalization. The burgeoning business of growing pot raises the specter of corporate agriculture with its threats to human health and natural ecosystems. Are there ways to enjoy weed while challenging racism and corporate domination over the environment?

An Attack on Black and Brown Cultures

Spanish-speaking people, who have lived in the US since it stole half of Mexico’s land, have a tradition of smoking marijuana. Amid a growing fear of Mexican immigrants in the early twentieth century, hysterical claims about the drug became widespread, such as allegations that it caused a “lust for blood.” The term cannabis was largely replaced by the Anglicized marijuana, perhaps to suggest the foreignness of the drug. Around this time many states began passing laws to ban pot.

In “Why Is Marijuana Illegal in the US?” Amy Tikkanen wrote that in the 1930s, Harry J. Anslinger, head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, turned the battle against marijuana into an all-out war. He could have been motivated less by safety concerns—the vast majority of scientists he surveyed claimed that the drug was not dangerous—and more by a desire to promote his newly created department. Anslinger sought a federal ban on the drug, and initiated a high-profile campaign that relied heavily on racism. Anslinger claimed that the majority of pot smokers were minorities, including African Americans, and that marijuana had a negative effect on these “degenerate races,” such as inducing violence or causing insanity.

Furthermore, he noted, “Reefer makes darkies think they’re as good as white men.” Anslinger oversaw the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937. Although that particular law was declared unconstitutional in 1969, it was augmented by the Controlled Substances Act the following year. That legislation classified marijuana—as well as heroin and LSD, among others—as a Schedule I drug. Racism was also evident in the enforcement of the law. African Americans in the early 21st century were nearly four times more likely than whites to be arrested on marijuana-related charges—despite both groups having similar usage rates.

In her 2016 film, 13th Amendment, producer, Ava Duvernay documented drug laws and policies which increased incarceration rates of Black and brown people over the last six decades.

| Year | US Prison Population |

|---|---|

| 1970 | 300,000 |

| 1980 | 513,900 |

| 1985 | 759,100 |

| 1990 | 1,179,200 |

| 2000 | 2,015,300 |

| 2020 | 2,300,000 |

President Nixon’s “War on Crime” of the 1970s targeted protests by the anti-war movement as well as liberation movements by gays, women, and Blacks. “Crime” became a code word for race. Nixon’s Adviser, John Ehrlichman, admitted that the “War on Drugs” was all about throwing Black people into jail to disrupt those communities. These efforts were to gain southern voters.

In the 1980’s, President Reagan’s “War on Drugs” portrayed drugs as an “inner city problem,” allowed for mandatory sentencing for crack cocaine, and tripled the federal spending on law enforcement. The War on Drugs became a war against Black and Latino communities, with huge chunks of Black and brown men disappearing into prison for a “really long” time. The exploding mass incarceration rates felt genocidal. This was again pandering to racist voters.

In his effort to appear “tough on crime” during the 1990’s, President Bill Clinton pushed the $30 billion Federal Crime Bill which expanded prison sentences, incentivized law enforcement to do things we now consider abusive, and militarized local police forces. Increased incarceration rates due to the Clinton administration included introduction of the terms “super predators,” Mandatory Minimum Sentences, “Truth in Sentencing” (which eliminated parole), and “three strikes and you’re out” laws whereby those convicted of three felonies were mandated to prison for life. Such a criminal justice system needs constant feeding of young men and women of color.

Racism during Marijuana Criminalization

Poverty plays a central role in mass incarceration – people put in prison and jail are disproportionately poor. The criminal justice system punishes poverty, beginning with the high price of money bail. The median felony bail bond amount ($10,000) is the equivalent of eight months’ income for the typical defendant. Those with low incomes are more likely to face the harms of pretrial detention. Poverty is not only a predictor of incarceration – it is also frequently the outcome, as a criminal record and time spent in prison destroys wealth, creates debt, and decimates job opportunities.

It’s no surprise that people of color — who face much greater rates of poverty — are dramatically overrepresented in the nation’s prisons and jails. These racial disparities are particularly stark for Black Americans, who make up 38% of the incarcerated population despite representing only 12% of US residents.

Police, prosecutors, and judges continue to punish people harshly for nothing more than drug possession. Drug offenses still account for the incarceration of almost 400,000 people, and drug convictions remain a defining feature of the federal prison system. Police still make over one million drug possession arrests each year, many of which lead to prison sentences. Drug arrests continue to give residents of over-policed communities criminal records, hurting their employment prospects and increasing the likelihood of longer sentences for any future offenses. The enormous churn in and out of correctional facilities is 600,000 persons per year. There are another 822,000 people on parole and a staggering 2.9 million people on probation – 79 million people have a criminal record; and 113 million adults have immediate family members who have been to prison.

One in five incarcerated people is locked up for a drug offense. Four out of five people in prison or jail are locked up for something other than a drug offense — either a more serious offense or a less serious one. The terms “violent” and “nonviolent” crime are so widely misused that they are generally unhelpful in a policy context. People typically use “violent” and “nonviolent” as substitutes for serious versus nonserious

Decriminalization Reinvents Marijuana Racism

The decriminalization which is sweeping across the US carries with it the obvious facts that (a) pot is not and never has been a dangerous drug, and (b) criminalizing drugs has never brought anything positive. This suggests that those who have been victimized were done so wrongfully and therefore should be compensated for the wrongs done to them. However, victims have been predominantly people of color and American racism reappears during the decriminalization phase in the form of trivializing harms done and offering restitution that barely scratch the surface of what is needed.

Prior to addressing the shortcomings for wrongful damages for marijuana laws, the US should publicly apologize for the wrongheaded and thoroughly racist “War on Drugs” and pledge to compensate those who have suffered from it in ways that are comparable to cannabis-related issues below.

Victims should be compensated for time spent in jail. Prisoners might receive compensation for labor performed in prison; but it can be as low as $0.86 to $3.45 per day for most common prison jobs. At least five states pay nothing at all. Private companies using prison labor are not the source of most prison jobs. Only about 5,000 people in prison — fewer than 1% — are employed by private companies through the federal PIECP (Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program), which requires them to pay at least minimum wage before deductions. (A larger portion work for state-owned “correctional industries,” which pay much less. But this still only represents about 6% of people incarcerated in state prisons.)

There cannot be a serious discussion of compensating victims if many continue to rot in jail. They must be release immediately, regardless of what state they are in. Many of those released have not had records of their arrests, convictions and sentencing cleared (“expunged”). According to Equity and Transformation Chicago, there is a 5-8 year wait for expunging records. Records must be expunged as rapidly as would be done if it really affected people’s lives (because it does).

A core component of repairing harm done to those imprisoned would be prioritizing them (according to amount of jail time served) to receive licenses for growing, processing, transporting and dispensing marijuana. Various states have taken baby steps in the right direction. For example, Chicago’s Olive Harvey College is offering training in cannabis studies to those with past marijuana arrests. Participants receive “free tuition, a $1,000 monthly stipend, academic support and help with child care, transportation and case management.” As of March, 2022 there were 47 studying for jobs as growers, lab directors and lab or quality control technicians.

Another effort pointing forward is New York’s program to grant licenses for marijuana storefronts for individual or family members who have been imprisoned for a marijuana-related offense. An executive for the program expects 100-200 licenses to go to such victims.

Let’s put these model programs in perspective. Nice as they are, 47 students receiving study grants in Chicago and 100-200 retail licenses in New York do not even make a dent in the over 867,000 who have been arrested.

While current programs are infinitesimally small, barriers to legal victims are enormous. Missouri grants licenses only to those “having legal marijuana experience” (such as handling legal medical cannabis) to apply for licensing for growing, dispensing, and processing. Illinois denies licenses and loans to felons, even though 1 in 3 Chicago adults have a criminal record. Illinois also prevents those with cannabis-related convictions from entering the cannabis industry by its high application fees.

Financial barriers for marijuana victims to receive licenses seem insurmountable. People and communities negatively impacted by the War on Drugs have high incarceration rates and lowaverage salaries due to limited job opportunities by ex-felons. Therefore, they lack the financial resources for high non-refundable application fees ($10,000 to $50,000) awarded in lotteries to match the state-designated number of growers, dispensaries, processors, and transporters. In Illinois, access to credit and small business loans are difficultfor persons with criminal records to obtain. Each dispensing organization applicant must have at least $400,000 in liquid assets. That is why people of color cannot participate as owners of legalized marijuana businesses in Illinois.

Industrial Agriculture Poisons Marijuana Cultivation.

Unfortunately, even if all these barriers were to be overcome, there would be serious health issues throughout the marijuana industry, whether legal or illegal. If people of color receive priority in all phases of the industry, then a new form of environmental racism will emerge. People in that industry will become part of the environmental destruction to their communities while they experience damage to their own health from pesticide poisoning.

An excellent review of concerns with cultivation of cannabis by a team working with Zhonghua Zheng finds it heavily associated with environmental and health concerns whether it is grown outdoors or indoors. Needing considerable water, cannabis requires twice as much water as wheat, soybeans and maize. Diverting water to irrigate cannabis crops often results in dewatered streams affecting other vegetation. Water quality is also worsened (especially by illegal growers) by use of herbicides, insecticides, rodenticides, fungucides and nematodes.

Human health problems which can be linked to chronic pesticide exposure include memory and respiratory issues as well as birth defects. Other health effects are weakened muscle functioning, cancer and liver damage. The organization Beyond Pesticides documents serious threats due to two factors: (a) “Pesticide residues in cannabis that has been dried and is inhaled have a direct pathway into the bloodstream;” and, (2) up to “69.5% of pesticide residues can remain in smoked marijuana.”

Perhaps the most overlooked source of pesticide poisoning is due to the synthetic piperonyl butoxide (PBO), which is a synergist, used to boost the effectiveness of active ingredients in pesticides. PBO can itself damage health due to neurotoxicity, cancer and liver problems.

Fertilizers and pesticides make their way into surface water, groundwater and soil, where they threaten the food supply. The high demand for weed affects watersheds, having damaging effects at least for endangered salmonid fish species and amphibians including the southern torrent salamander and coastal tailed frog.

Outdoor cannabis farms disturb fine-sediment adjacent to streams, thereby threatening other rare and endangered species. Its cultivation can contribute to deforestation and forest fragmentation. Fertilizers used for cannabis hurt air quality due to the release of nitrogen. Excess nitrogen increases soil acidification and well as water eutrophication.

Growing cannabis indoors raises its own issues, most notably health risks from exposure to mold and pesticides. Mold in damp indoor environments is associated with wheeze, cough, respiratory infections, and asthma symptoms in sensitized persons.

Perhaps the most surprising problems with indoor cultivation of cannabis is its effects on climate change via electricity. This is due to its annual $6 billion energy costs in the US, making it responsible for at least 1% of total electricity. Inevitably, decriminalization will lead to increased use of energy.

The major sources of energy usage are lighting and microclimate control. High-intensity lighting alone accounts for 86% of electricity use for indoor cannabis. Dehumidification systems are used to create air exchanges, temperature, ventilation and humidity control 24 hours per day. Due to the complexity of indoor requirements, growing one kilogram of processed marijuana can result in 4600 kilograms of CO2 emissions!

Environmental and health problems with growing marijuana will intensify greatly if decriminalization allows control by corporate agriculture. The so-called “Green Revolution” emphasizes use of enormous monocultures which maximize ecological destruction from extreme use of irrigation and fertilizers.

As of early 2022, at least 36 US states have adopted some form of decrimalization of marijuana, adding to the explosion of businesses in every phase of its production. In 2018, Bloomberg reported “Corona beer brewer Constellation Brands Inc. announced it will spend $3.8 billion to increase its stake in Canopy Growth Corp., the Canadian marijuana producer with a value that exceeds C$13 billion ($10 billion).”

Coca-Cola has been eyeing the market for drinks containing CBD which eases pain without getting the user high. Pepsi may have jumped the gun on Coke. A New Jersey hemp and marijuana producer, Hillview, has an agreement with Pepsi-Cola Bottling Co. of New York to makes CBD-infused seltzers which would sell for $40 per eight-pack. The deal aims to cover Long Island, Westchester and all five New York boroughs.

With industrial giants like Coke and Pepsi jumping into the cannabis market, it is a sure bet that they will not be buying marijuana from thousands of mom-and-pop growers. Look for big soft drink to seek contracts with big ag.

The commercial growth of crops based on monoculture (a single or very few crops grown) becomes a breeding ground for pests, creating an artificial need for control via chemical poisons. A fundamental principle of organic agriculture is that growing 10, 15 more more plant species together reduces any need for chemicals. In the corporate ag model, if the single species grown is invaded by pests, then the entire crop can be lost. In the organic model the farmer anticipates that 1, 2 or 3 may be hurt by pests, but the majority will survive.

According to farmer Patrick Bennett, “for a fraction of the cost of a single bottle of synthetic liquid fertilizer, you can get the same, if not better yield, flavor, and cannabinoid content in your crop at home by simply using organic farming practices.” Marijuana has been grown for centuries (or millennia) without pesticides. Current organic growers have found five plant-based insecticides that protect their crops well:

- Neem oil is “extracted from the seeds and fruit of the tropical neem tree, [and] controls many insects, including mites, and prevents fungal infections, like powdery mildew.”

- Azadirachtin controls “control over many insects, including mites, aphids, and thrips” but does not provide fungal protection.

- Pyrethrums kills insects that attack cannabis plants, including thrips. Pyrethrins, however, the synthetic version of pyrethrums, should not be used due to their environmental persistence.

- Bacillus Thurengensis (BT) is very effective in controlling larval insects and fungus gnats.

- Beneficial Nematodes are microscopic organisms occurring naturally in soil, keeping it healthy while controlling soil-born pests such as fungus gnats.

Techniques such as these have proven effective. Mike Benziger told interviewer Nate Seltenrich that he grows fruits, vegetables and medicinal herbs along with cannabis. He includes multiple plants that attract insects like ladybugs and lacewings that gobble up harmful mites and aphids. Organic growers often rely on mulching and crop rotation. Such methods are especially critical for protecting workers growing the plants, neighboring wildlife, farm owners, distributors and, of course, marijuana users.

As of 2015, Maine was prohibiting use of any pesticides. Yet, its is important to remember that legislation can be weakened or repealed by subsequent laws, making it critical to have enduring guidelines. Such guidelines should include practices like those in Washington DC and Maine which require producers to demonstrate knowledge of organic growing methods.

Moving Forward

Since federal law classifies marijuana as a narcotic there are no federal guidelines for growing it. This makes it tempting to demand that it be declassified and brought under the auspices of bodies like the Environmental Protection Agency. This is a worthwhile goal, but the problem is that federal and state bodies are controlled by corporate powers seeking the weakest standards possible. Goals such as the following should be stated to counter racism and have genuine environmental protection with real (not fake) organic standards:

1. Restitution must begin with an apology which acknowledges that criminalization of marijuana included an attack on those cultures using it; was a part of a greater attack which used drugs as one of many weapons to destroy communities; and caused suffering for an enormous number of individuals.

2. All communities affected by criminalization of marijuana and the larger attack upon them should decide what financial and cultural restitution they should receive.

3. Individuals harmed by marijuana criminalization should receive financial compensation for any arrest, trial, incarceration and post-incarceration damages. Funds for growing, preparing and dispensing legalized marijuana should be made in direct proportion to the harm that individuals have suffered – those who have been harmed the most should receive the greatest compensation. In particular, the greater the harm an individual has suffered, the higher priority that individual should have for receiving a license related to dispensing marijuana.

4. Organic growing must be a core component of protecting the health of marijuana workers, producers and users. All who grow marijuana must receive free education on how to do so without the use of chemical poisons (“pesticides”). This must include how to intersperse marijuana with other crops so that pests are not as threatening as they are with monocultures. All who grow, process and disperse marijuana must obtain certification that their product is free of chemical contaminants. There should be no limitations on the number of marijuana plants an individual may grow, as long as those plants are grown with genuine organic principles.

Prior to decriminalization, health and environmental damages of growing and using marijuana were more or less similar for all ethnic and cultural groups. But that will not continue to be the case if restitution for damages from criminalization are put into place. If those hurt most by harassment and incarceration for marijuana receive priority for licenses to produce and distribute cannabis, they will receive the most pesticide poisoning if organic methods are not required. The only way to avoid continued harm to those previously victimized is to employ organic cultivation.

Abolition of exploitation of all agricultural workers requires similar restrictions on chemical use when growing all herbs, fruits and vegetables. Organic growing of cannabis should become a model for transferring production via corporate megafarms using mono cropping, chemicals, and exploited labor to organic methods based on small farms, chemical-free growing for local communities and good treatment for workers encouraged to form strong unions for collective self-protection.

[The Green Party of St. Louis adopted a marijuana perspective that synthesizes anti-racism with organic growing principles. You can read it at: marijuana-platform.]Facebook

This article was posted on Saturday, May 14th, 2022 at 9:32am and is filed under Crime, Drug Wars, Marijuana, Racism.