It’s no coincidence that three Rust Belt states with large populations of Catholics helped put the Democrats back in the White House in January of 2021.

Courtesy of Ryan Burge

November 6, 2020

By Ryan Burge

Produced in collaboration with the Association of Religion Data Archives.

(RNS) — It has been three presidential election cycles since a Catholic candidate stood for the office, and while some things have changed — not least the pope — the importance of northeast Catholic voters is as important as ever.

According to VoteCast, the Associated Press’ analysis of the vote, Joe Biden earned a 50-50 split among Catholics in 2020. That’s a stark difference from the significant margin that President Trump enjoyed in his 2016 victory over Democrat Hillary Clinton, when he garnered nearly 60% of the Catholic vote.

What made the difference this time around?

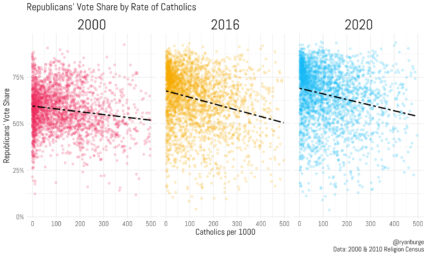

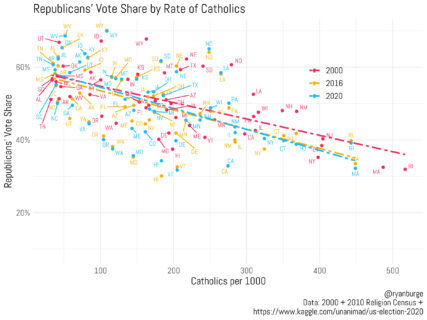

To answer that question, I turned to the Religion Census data from the Association of Religion Data Archives to examine how the share of Catholics in U.S. counties related to their vote for the Republican candidate in the elections of 2000, 2016, and 2020.

Courtesy of Ryan Burge

It turns out that while Trump stays on par (or better) with the Catholic vote nationwide, the GOP’s share of the Catholic vote has been slowly dropping wherever Catholics are more thickly clustered. Trump’s 8 percentage point drop from 2016 with these voters — especially in the swing states of Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania — is a continuation of a longstanding trend.

On the first scatterplot chart, the dashed line shows that in counties with very low shares of Catholics, Trump’s 65% share of Catholic voters in 2016 outpaced George W. Bush’s haul in 2000 of just under 60%. In highly Catholic counties, however, Trump did only slightly better, with about 55% of the vote compared to Bush, who was closer to 52%.

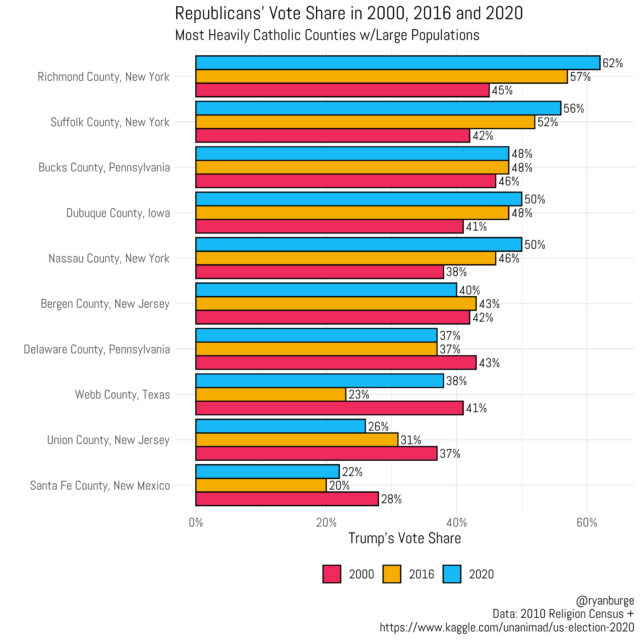

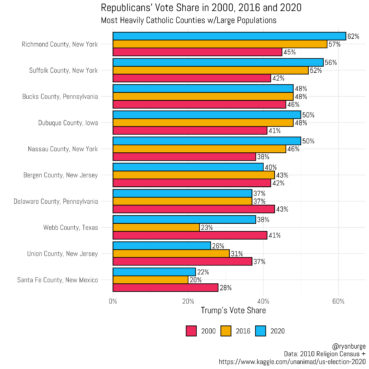

When I took a closer look, examining only larger Catholic-rich counties (where at least 50,000 votes were cast in 2020), there was no discernible pattern. At the county level, too many other factors can affect the direction of the vote, particularly, it seems, what kind of Catholics are dominant.

For instance, on Staten Island, New York, (Richmond County) and the East End of Long Island (Suffolk), whose Catholics tend to be well-settled descendants of 19th-century European immigrants, Trump did much better this year than George W. Bush did two decades ago.

However, in Union County in northern New Jersey, which has a large population of more recent Hispanic immigrants, Trump only earned 26% of the vote, down 11 percentage points from Bush’s total in 2000. The same pattern is true in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where Trump did 6 points worse than Bush did.

Courtesy of Ryan Burge

At the state level, however, the story came back into focus.

In each of the three elections under study, the Republican earned between 55% and 58% of the Catholic vote. However, as the share of Catholics in the state increases, Trump actually loses votes more sharply than Bush did. In the 2000 election, for every 10% increase in the percentage of Catholics in a state, Bush lost 4.9% more of the vote. For President Trump in 2020 that decline was a bit steeper at 5.8%. That rate is a bit worse than his performance in 2016 when it was a 5.3% decline.

The Republicans’ ability to draw these Catholics in densely Catholic states, in other words, is declining, but the decline has accelerated under Trump: While the GOP’s declining share among clustered Catholics fell 1% from 2000 to 2016, it dropped another 0.50% in just four years.

To put all of this in perspective, if Pennsylvania had the lighter Catholic concentration of a place like Iowa, the president would be enjoying a 55% vote margin, all else being equal, in the Keystone State and may well have kept the White House.

Courtesy of Ryan Burge

Obviously, the electorate of a state hinges on much more than religious concerns, but it’s no coincidence that three Rust Belt states with large populations of Catholics helped put the Democrats back in the White House in January of 2021.

(Ryan Burge is an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University and a pastor in the American Baptist Church. He can be reached on Twitter at @ryanburge. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

Ahead of the Trend is a collaborative effort between Religion News Service and the Association of Religion Data Archives made possible through the support of the John Templeton Foundation. See other Ahead of the Trend articles here.