Low-cost 3D method rapidly measures disease impacts on Florida’s coral reefs

FAU Harbor Branch technique can be used for widespread coral disease intervention, mitigation and management strategies

Peer-Reviewed PublicationIMAGE: THE ANIMATION DEPICTS AN SFM 3D ROTATING MODEL, WHICH CAN PROVIDE GREATER INSIGHTS INTO THE SPATIOTEMPORAL DYNAMICS AND IMPACTS OF CORAL DISEASES ON INDIVIDUAL COLONIES AND CORAL COMMUNITIES THAN SURVEYS OR VISUAL ESTIMATES OF DISEASE PROGRESSION ALONE. view more

CREDIT: FLORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY, HARBOR BRANCH OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTE

Stony coral tissue loss disease manifests as lesions of necrotic tissue that spread across coral colonies, leaving behind dead coral skeletons. Since 2014, this highly virulent disease has contributed to substantial declines of reef-building coral in Florida, impacting more than 20 coral species. The need for widespread reef monitoring and novel surveys are imperative for disease mitigation strategies. However, the various techniques currently used all require individual evaluation and often rely on visual estimates by divers in the field.

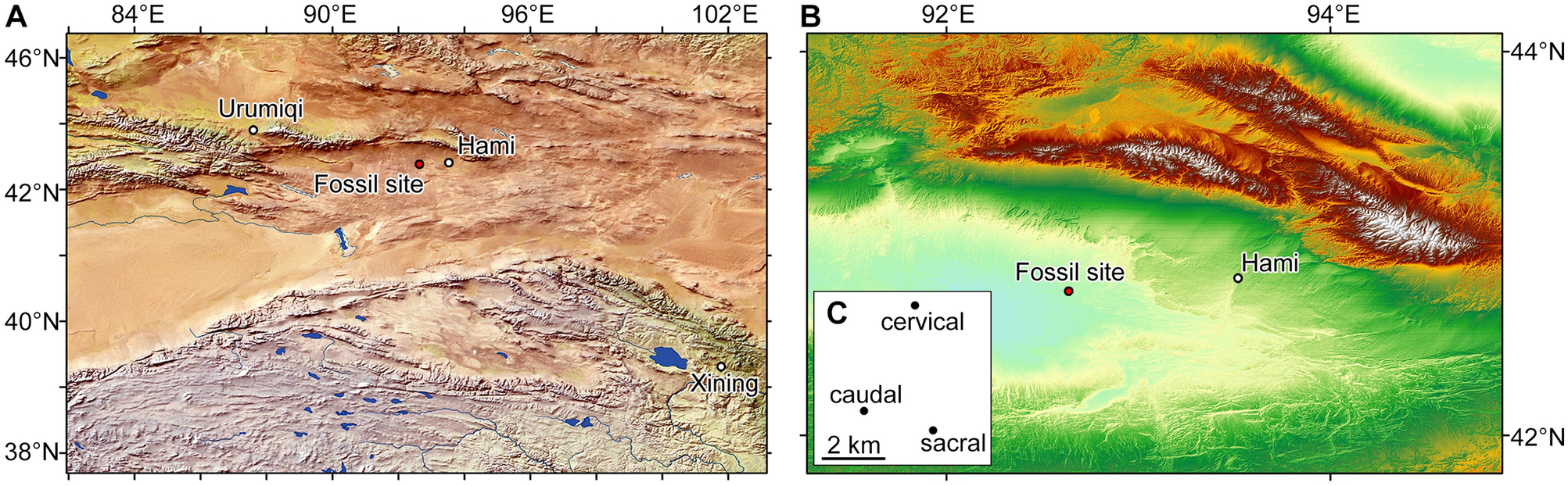

A low-cost and rapid 3D technique is helping scientists to gain insight into the colony- and community-level dynamics of the poorly understood stony coral tissue loss disease. Researchers from Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute adapted Structure-from-Motion (SfM) photogrammetry to generate 3D models for tracking lesion progression and impacts on diseased coral colonies. By combining traditional diver surveys and with 3D colony fate-tracking, the team determined the impacts of disease on coral colonies at study sites throughout Southeast Florida in St. Lucie Reef, Jupiter, Palm Beach and Lauderdale-by-the-Sea.

Results of the study, published in PLOS One, demonstrated that the prevalence of stony coral tissue loss disease varied significantly across location, but not through time. St. Lucie Reef and Lauderdale-by-the-Sea sites were highly impacted by coral disease, while study sites in Jupiter and Palm Beach had lower disease prevalence. The highest disease values observed in this study were between 21 to 43 percent at St. Lucie Reef. However, no site reached the highest reported disease prevalence values of 60 percent observed near Miami in 2014.

“We observed an increase in disease prevalence during the spring of 2018, which was honestly unexpected. Prevalence values for other described coral diseases such as white syndrome, white band, black band, and white pox often increase during the summer months as water temperatures increase,” said Joshua D. Voss, Ph.D., senior author, an associate research professor at FAU Harbor Branch and executive director of the NOAA Cooperative Institute for Ocean Exploration, Research, and Technology. “Stony coral tissue loss disease prevalence does not appear to have a strong positive correlation with temperature as has been observed for other coral diseases, but potential environmental cofactors that may drive disease prevalence need to be examined further.”

Findings from the study also indicated that total colony area and healthy tissue area on fate-tracked colonies decreased significantly over time, capturing the amount of coral tissue lost to disease. However, disease lesions themselves did not change in size over time and were not correlated with total colony area. These results suggest that targeting intervention efforts on larger colonies may maximize preservation of coral cover.

“Since stony coral tissue loss disease is a progressive and necrotic infection, the area of tissue loss, or proportion of tissue loss, may represent more impactful metrics for quantifying the severity of infection as opposed to disease lesion area or percent affected tissue,” said Ian Combs, the study’s lead author and recent M.S. graduate from Voss’ lab at FAU Harbor Branch. “Traditional coral surveys combined with 3D photogrammetry can provide greater insights into the spatiotemporal dynamics and impacts of coral diseases on individual colonies and coral communities than surveys or visual estimates of disease progression alone.”

CAPTION

The composite of photographs show stony coral tissue loss disease lesions on a colony of Montastraea cavernosa. (a) a photograph of fate-tracked, stony coral tissue loss disease-infected coral colony, (b) rendered SfM 3D model, (c) characteristic of stony coral tissue loss disease lesion, and, (d) necrotic tissue.

CREDIT

Florida Atlantic University, Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute

Since 2014, Florida’s Coral Reef has experienced an ongoing outbreak of the newly-described coral disease responsible for widespread coral death throughout the Tropical Western Atlantic. The disease first appeared in the summer of 2014 following the dredging of Government Cut in Miami-Dade County. In subsequent years, reports of stony coral tissue loss disease infections have increased and spread from Miami-Dade County along the Florida Reef Tract and into the wider Tropical Western Atlantic. To date, the disease has spread north to the northern terminus of the Florida’s Coral Reef in Martin County and south to the Dry Tortugas in Monroe County, with additional outbreaks observed in at least twelve territories throughout the Tropical Western Atlantic.

The ultimate goal of this work is to increase widespread application of this and similar techniques to improve the design, implementation, and success of coral disease intervention, mitigation, and management strategies.

“Quantitative 3D approaches such as the method we used can improve our understanding of the ecology and impacts of coral diseases on coral reef ecosystems, and may guide colony selection in future disease intervention strategies,” said Voss. “We’ll use this information to optimize our efforts to slow disease outbreaks in Southeast Florida and the Dry Tortugas.”

Combs is now a coral reef ecosystem biologist at Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium. Additional co-authors on the study include Michael Studivan, Ph.D., a graduate of FAU’s integrative biology doctoral program and an assistant scientist at the University of Miami CIMAS/NOAA AOML; and Ryan Eckert, an FAU integrative biology Ph.D. student in the Voss Lab.

This research was supported by awards to Voss from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (B430E1 and B55008), the Environmental Protection Agency (South Florida Geographic Initiative award X7 00D667-17), and the NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program (award NA16NOS4820052). Additional funding was awarded to Combs by the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute Foundation through the Indian River Lagoon Graduate Research Fellowship.

- FAU -

About Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute:

Founded in 1971, Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute at Florida Atlantic University is a research community of marine scientists, engineers, educators and other professionals focused on Ocean Science for a Better World. The institute drives innovation in ocean engineering, at-sea operations, drug discovery and biotechnology from the oceans, coastal ecology and conservation, marine mammal research and conservation, aquaculture, ocean observing systems and marine education. For more information, visit www.fau.edu/hboi.

About Florida Atlantic University:

Florida Atlantic University, established in 1961, officially opened its doors in 1964 as the fifth public university in Florida. Today, the University serves more than 30,000 undergraduate and graduate students across six campuses located along the southeast Florida coast. In recent years, the University has doubled its research expenditures and outpaced its peers in student achievement rates. Through the coexistence of access and excellence, FAU embodies an innovative model where traditional achievement gaps vanish. FAU is designated a Hispanic-serving institution, ranked as a top public university by U.S. News & World Report and a High Research Activity institution by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. For more information, visit www.fau.edu.

JOURNAL

PLoS ONE

DOI

10.1371/journal.pone.0252593

METHOD OF RESEARCH

Observational study

SUBJECT OF RESEARCH

Not applicable

ARTICLE TITLE

Quantifying impacts of stony coral tissue loss disease on corals in Southeast Florida through surveys and 3D photogrammetry

ARTICLE PUBLICATION DATE

25-Jun-2021

COI STATEMENT

None