The first weekend of November 2023, Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) held its annual convention at a hotel near O’Hare Airport outside of Chicago. It was the forty-eighth convention since the rank-and-file union reform movement’s founding in 1976. The mood was confident and upbeat, with organizers announcing an attendance of five hundred Teamster members from across the country. It was the largest TDU convention since 1997.

The Friday dinner banquet speaker was International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) general president Sean O’Brien, who took stock of what his administration had accomplished since taking office in March 2022. He focused especially on the union’s contract fight at package giant UPS this past summer, which culminated in the best contract ever negotiated at the company. He also spoke of the union’s plans to organize Amazon, an existential threat to the union.

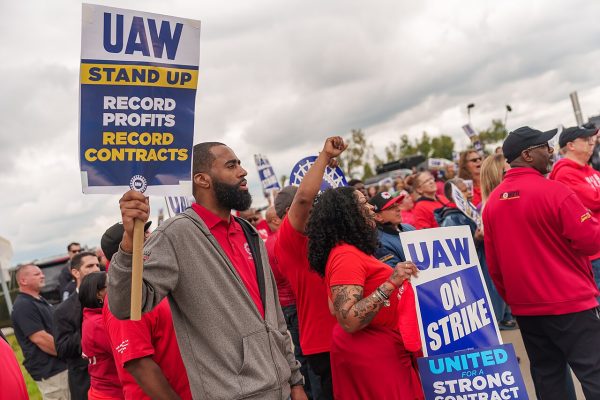

On Saturday evening, the featured speaker and guest of honor at the dinner banquet was United Auto Workers (UAW) president Shawn Fain, who was fresh off of leading an unprecedented strike against all three of the Big Three automakers, dubbed the “Stand-Up Strike.” The six-week strike had resulted in the best auto contracts negotiated in decades, with Fain grabbing national headlines for his militant class-war message, combined with an “aw shucks” demeanor befitting his small-town roots in Kokomo, Indiana.

On stage at the TDU convention, though, Fain was playing the role of fiery working-class tribune far more than that of friendly uncle. He brought the crowd of rank-and-file Teamster activists to its feet with a no-holds-barred speech that denounced the billionaire class and held up the Stand-Up Strike as a fight not just for UAW autoworkers, but the entire working class. Importantly, he connected the new militancy in the UAW directly to the rank-and-file union reform movement that TDU has played a key role in building for the past several decades. As he put it, “there is no Stand-Up Strike without TDU.” As Fain left the stage, the crowd erupted in spontaneous chants of “Eat the Rich,” Fain’s signature slogan, appropriated from a profile of him in the New York Times.

An Improbable Scenario

This entire scenario would have been improbable a year ago, and unthinkable seven years ago. In November 2022, Fain was still a long-shot presidential candidate in the first-ever direct election for top officers in the UAW. He was still a few weeks away from being part of one of the biggest upsets in US labor history, and a few months away from taking office as the first directly elected president of the UAW. In late 2016, O’Brien was still a loyal lieutenant of old-guard Teamster general president James P. Hoffa, who had then been in office for close to two decades. Far from being friendly with TDU, O’Brien had served a two-week suspension from his IBT positions in 2014 for threatening TDU activists who were challenging an ally of his in Rhode Island Local 251 (O’Brien has since apologized and expressed regret for his actions, and the Local 251 Teamsters he once threatened are now some of his staunchest supporters).

For its part, TDU had kept up the fight through the years of the Hoffa administration, but it was hard to point to concrete gains beyond some defensive victories. The 2016 leadership election campaign had been a shot in the arm though, as TDU-aligned candidate Fred Zuckerman, head of Louisville Local 89, had come within a few thousand votes of defeating Hoffa, and TDU-aligned candidates won spots on the IBT General Executive Board for the first time since 1996. Still, times were tough, and TDU organizers would work hard to build TDU conventions that were half the size of this year’s event.

As for the UAW, starting in 2017, it was in the thick of a corruption scandal that saw thirteen top union officials, including two former presidents, serve prison time. The federal investigation into the union uncovered cartoonish levels of malfeasance, with top UAW officials literally taking company payoffs in exchange for contract concessions, and using members’ dues money to fund lavish getaways, expensive cigars, vacation homes, and more. Meanwhile, successive generations of UAW leadership had given away the store at the bargaining table, allowing the auto companies to introduce multiple tiers of workers who were paid different rates for doing the same work, and routinely agreeing to concessions in exchange for vague company promises of new investment in plants.

With UAW wages and working conditions eroding, it is unsurprising that they found themselves unable to organize any new auto plants, even as unionized companies used the nonunion competition as a rationale for driving down standards even further. People looking for signs of life in the US labor movement were not looking to the UAW.

Things are different now. Amid a new resurgence of worker organizing and militancy, the Teamsters and the UAW are at the forefront. The UPS contract campaign this summer, followed by the Big Three auto campaign in the fall, mobilized hundreds of thousands of workers around ambitious demands. In both cases, the campaigns resulted in the best contracts in decades.

Of course, it’s important to remember that this is a low bar, as for decades the previous IBT and UAW leaderships had been negotiating concessionary contracts. Given how much ground was left to make up, some workers felt that the contracts left unfinished business and wanted to hold out for more. But this was far more indicative of how the contract fights raised expectations than it was of contract shortcomings. Both contracts represented a decisive shift away from the concessions of the recent past.

How did we get here? And what might this mean for the possibility of a revitalized US labor movement more broadly?

Seizing the Opportunity

While proceeding on parallel tracks and different timelines, the transformations of the IBT and UAW share some strong similarities. Most fundamentally, both involved the combination of top-down government intervention to address massive union leadership corruption, and bottom-up rank-and-file reform movements capable of seizing the opportunity that government intervention created.

Government intervention in the internal affairs of labor unions can be fraught, but in the cases of the IBT and UAW, it was necessary to dislodge deeply entrenched political machines that had stifled member dissent for decades while doling out all kinds of goodies to loyalists, often at the expense of average workers. This had insulated union leadership from criticism and created conditions for the obscene levels of corruption that took hold in both unions.

In the case of the IBT, the corruption took the form of outright Mafia control. The US government’s complaint filed in US v. IBT in 1988 charged that “[The IBT] has been a captive labor organization, which La Cosa Nostra figures have infiltrated, controlled and dominated through fear and intimidation and have exploited through fraud, embezzlement, bribery and extortion.” Several investigations uncovered that top Teamster officials sought Mafia approval for key decisions, and mob bosses would often sign off on who would serve on the IBT’s General Executive Board. Several locals were essentially mob front operations, Teamster pension funds served as mob banks for questionable loans, and members who asked too many questions could risk incurring the wrath of mob enforcers.

As for the UAW, corrupt forces took the form of an outfit known as the Administration Caucus. Formed in the 1940s around future UAW president Walter Reuther, as of the union’s 1947 convention it became the ruling party in the UAW’s one-party state. It was at the 1947 convention that Reuther and his allies won a yearslong battle to eliminate what had been, until then, a vibrant if at times unruly system of competing caucuses within the union. After 1947, it became virtually impossible to advance within the UAW leadership without joining the Administration Caucus — and joining the caucus generally meant a strict, unquestioning conformity with decisions handed down from on high.

Unlike the IBT leadership, Reuther and his UAW were not personally corrupt — the corruption in the UAW wouldn’t come until later. In the postwar decades, the UAW positioned itself as a dynamic force at the forefront of American liberalism. Reuther’s UAW provided financial and logistical support for New Left and civil rights organizations in the 1960s, including the meeting space for Students for a Democratic Society to draft the Port Huron Statement in 1962, and buses and funding for the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Even in the 1980s, years after Reuther’s death, the union took a strong stance against South African apartheid when it was not popular to do so, and one of Nelson Mandela’s stops on his tour of the United States upon being released from prison was to address a massive crowd at Tigers Stadium in Detroit at the UAW’s invitation, where he wore a UAW jacket.

There were limits to the UAW’s liberalism, as when Reuther moved to squelch the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s effort to be seated in place of the “official” segregationist delegation at the 1964 Democratic Party convention, or when, in 1973, then UAW vice-president Douglas Fraser led a contingent of one thousand UAW staffers and officials armed with baseball bats and pipes to break up a wildcat strike of predominantly black workers at the Chrysler Mack Avenue Stamping Plant over issues of speedup and plant safety. But certainly, in comparison to the Teamsters, the UAW at least attempted to articulate a broader social vision.

Over time though, the Administration Caucus’s focus on discipline and loyalty above all else did culminate in corruption. What started with the union agreeing to contract concessions in the name of keeping companies “competitive” and saving jobs in the 1980s led to the scandal that blew up in the 2010s and dragged on until 2022. In both the IBT and UAW, many members knew that something was wrong, and tried to take action to change things. TDU led the charge in the Teamsters, exposing corruption, helping workers organize at the local level, and calling for basic democratic reforms in the union. The path was more circuitous in the UAW, with a succession of reform groups trying to take on the Administration Caucus. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM), led by black autoworkers and primarily based in and around Detroit. In the 1970s, the United National Caucus organized around shop-floor issues in the auto plants and fought for democratic reforms. From the 1980s through the 2000s, it was New Directions that sounded the alarm about the UAW’s turn toward concessionary bargaining and labor-management partnership. A small group of reform veterans kept the flame alive through the 2000s and 2010s with Autoworker Caravan, until Unite All Workers for Democracy (UAWD) was founded in 2019.

These reform groups were all scrappy and punched well above their weight. It was notable how their organizing managed to provoke responses from union leadership that were wildly out of proportion to their actual size and influence. But absent the leverage of government intervention, they simply didn’t have the strength to break the corrupt IBT and UAW political machines.

At the same time, government intervention itself would have been insufficient for reforming the unions. It only created the necessary conditions for reform by removing the most corrupt leadership elements, fragmenting the remaining incumbent leadership, and implementing democratic structural reforms. Without the decades of rank-and-file organizing of TDU and UAWD and its predecessor organizations, the transformations on display at this year’s TDU convention would have been unthinkable.

Understanding this interplay between top-down government intervention and bottom-up rank-and-file organizing is essential to make sense of the longer-term prospects for union reform. Because as the Teamsters case shows, the path of reform is rarely a straight line.

The Winding Road to Teamster Reform

The outcome of the 1988 federal court case against the IBT was a 1989 consent decree. While the US attorneys initially proposed a government trusteeship of the union as a remedy, TDU was able to intervene and convince the prosecutors to adopt an alternative for which they had long fought: direct member election of top union officers. Armed with the right to vote and government-supervised elections, Teamster members threw out the corrupt old guard and elected reformer Ron Carey, president of New York Local 804, in a three-way race. Carey was a pariah among IBT officials, but he had the backing of TDU and ran a relentless two-year grassroots campaign that put his slate over the top.

With TDU’s support, Carey cleaned house in the IBT and began setting the union on a different, more militant path. But he was also aided by a government-appointed Independent Review Board (IRB) that removed corrupt local officials and expelled them from the union. The culmination of the TDU-backed Carey coalition’s organizing was the 1997 UPS strike, widely hailed as one of the most significant labor victories of the 1990s. Rallying around the slogan “Part-time America Won’t Work!” the two-week strike shone a light on eroding job quality in the United States, and galvanized the public around the demand for good, full-time jobs. In the end, the Teamsters forced UPS to create ten thousand new full-time jobs by combining twenty thousand part-time jobs.

Carey and TDU were riding high after the UPS strike, but that wouldn’t last. On August 22, 1997, just three days after the UPS strike victory, a federal IBT election overseer overturned the results of the 1996 leadership election. Carey would later be barred from running again and then expelled from the union for life. While Carey was ultimately found personally innocent of any wrongdoing in court, the damage was done, and his expulsion stood. In a 1998 rerun election, the Teamsters old guard returned to power under the leadership of General President James P. Hoffa, son of notorious Teamster leader James R. Hoffa.

The younger Hoffa would hold office for the next twenty-three years, but the structural reforms that TDU won meant that he was unable to turn back the clock to the pre–consent decree era. Hoffa and his associates had to remain accountable to Teamster members in a way that their predecessors did not. Pockets of corruption remained, but the Hoffa administration was characterized much more by garden-variety, employer-friendly “business unionism” than the rampant mob domination of the past.

Because TDU maintained independence from Carey even as it supported him, it was able to survive. Throughout the Hoffa administration, TDU continued to organize members at the local level to enforce their contracts and hold local union officials accountable. They continued to back candidates to challenge the Hoffa administration at the level of the International, ensuring that Hoffa never ran uncontested. They also continued to defend the integrity of the independent election oversight process, which Hoffa repeatedly tried to dismantle. But TDU by itself was not powerful enough to challenge Hoffa’s grip on power.

However, as Hoffa’s tenure in office dragged on, his leadership coalition started to fray. More and more local leaders were getting fed up with concessionary contracts and lack of support from International leadership. In 2013, eighteen regional supplements to the national UPS contract were rejected, some multiple times. It took the IBT leadership close to a year to get all the supplements ratified. In this context, some prominent Teamster officials were now willing to break with Hoffa and challenge his leadership. In 2016, head of the important Louisville Local 89 and former Hoffa loyalist Fred Zuckerman came within a percentage point of unseating Hoffa, after switching sides and running with TDU’s support.

The final nail in the Hoffa administration’s coffin was the 2018 UPS contract.

The 2018 proposed contract was riddled with concessions, most notably the introduction of lower-tier “Article 22.4” drivers, who would do the same work as regular package car drivers but make less and have worse contract protections. In response, TDU spearheaded a Vote No movement that caught fire throughout the union. They found a willing ally in Sean O’Brien, another former Hoffa loyalist who helped build the campaign. This time, the Vote No forces succeeded in rejecting the entire contract. However, IBT leadership imposed the contract anyway, invoking an arcane provision of the union’s constitution and enraging members in the process.

When O’Brien announced his run for the IBT presidency, with Zuckerman as his running mate for general secretary-treasurer, TDU faced the question of how to relate to the challengers’ candidacy. O’Brien’s past relations with TDU had been frosty, making some within the Teamster reform movement reluctant to back him. However, previous elections had shown that TDU on its own did not have the breadth and depth of support necessary to unseat the Teamster old guard, even in its weakened state. Running a separate campaign would only have split the anti-Hoffa vote, increasing the likelihood that the old guard would remain in charge. Abstaining from making an endorsement would have sidelined TDU at a critical moment, likely condemning it to irrelevance. O’Brien may not have been TDU’s first choice, but the 2018 UPS contract had shown that the two could work together, and in the fall of 2019, TDU officially voted to endorse the O’Brien-Zuckerman slate.

Seeing the writing on the wall, Hoffa announced that he would not seek another term in February 2020. O’Brien and Zuckerman ended up running against pro-Hoffa officials Steve Vairma and Ron Herrera, whose lackluster campaign showed the degree to which the Hoffa political machine was exhausted. They went on to lose the 2021 election to the O’Brien–Zuckerman slate by a two-to-one margin.

This left TDU once again as a junior partner in a reform-oriented leadership coalition, as it was in the Carey administration. It has used that position to organize Teamsters on a previously impossible scale, most notably around the 2023 UPS contract campaign, where TDU played a critical role in developing strategy and running ground operations. Working together, the coalition was able to win the best UPS contract ever negotiated. Postcontract, TDU has pivoted to UPS contract enforcement along with continuing its work of helping Teamster members reform their union at the local level. As under Carey, it has worked closely with the administration while maintaining its independence.

The UAW Parallel

Recent events in the UAW are much more analogous to the situation in the Teamsters in the late 1980s and early 1990s. As with the IBT in 1989, UAW officials entered into a consent decree with federal prosecutors on January 29, 2021, to settle their corruption case. Whereas the IBT consent decree ordered direct election of top officers, the UAW consent decree ordered a member referendum to decide whether to adopt a system of direct election of top officers. It fell to UAWD, founded less than two years prior, to mount a campaign to win “one member, one vote” (1M1V). On December 2, 2021, when the votes were tallied, members had voted for 1M1V by a two-to-one margin.

With the right to vote secured, the next challenge was to find candidates to challenge the incumbent leadership. Decades of Administration Caucus control of the union leadership apparatus meant that there were very few officials willing to stick their necks out. Fain, like Carey in the IBT before him, was a maverick who was ostracized within the UAW leadership for his anticoncessions stance. That drew him toward UAWD, and meant that he was willing to put his staff job as an International representative on the line to challenge incumbent president Ray Curry. Curry had inherited the job from the retiring Rory Gamble, who in turn had been appointed after two former UAW presidents had been sent to prison as part of the corruption scandal.

Along with Fain, UAWD was able to assemble a partial slate of seven candidates (out of thirteen International Executive Board positions) to run on the Members United slate. Some were local UAW leaders, others were rank-and-file UAW members. Unlike TDU, UAWD did not have decades of prior organizing experience. But it was able to draw on the expertise of veterans of past UAW reform movements like New Directions, not to mention TDU leaders themselves. And whereas TDU had two years to campaign between the announcement of the leadership election and the actual vote, UAWD had less than a year.

Given the short timeline and UAWD’s lack of reach and resources, few expected Members United to win. The main goal was to establish the precedent of having contested leadership elections and holding union officials accountable. So it was a surprise to everyone when Fain and the entire slate prevailed.

Taking office just one day before the start of the UAW’s 2023 Bargaining Convention, which would set priorities for that year’s Big Three auto negotiations, Fain and Members United had to move quickly to set the union on a new path as they prepared for what would be a decisive test of their leadership. Taking several pages from the TDU playbook, they launched the first-ever contract campaign at the Big Three, mobilizing members behind an ambitious set of demands that sought to claw back decades of concessions and put the union back on offense. The result was the tactically innovative and shockingly successful Stand-Up Strike.

None of what Fain’s administration has accomplished in its few short months in office would have been possible without the organizing that UAWD did first to win the right to vote, then to get the Members United slate elected. But it’s equally important to understand that those wins would not have been possible without the opening created by the Administration Caucus corruption scandal and resulting government intervention. As with the Teamsters before them, the breakdown of the incumbent leadership and external intervention by the government created the conditions for union reform, but there also had to be an organized group of union members ready to seize the opportunity and actually reform the union.

What Lies Ahead

With the Big Three contracts now behind them, the new UAW leadership faces the deeper challenge of changing the culture of patronage and loyalty-first politics that gripped the union. So far, the approach has been to look outward, building off the momentum of the Stand-Up Strike with a bold plan to organize all thirteen nonunion US-based automakers. This responds to the core existential threat facing the union, as union density in the auto industry has plummeted from 60 percent to 16 percent in the past four decades, even as auto employment has remained stable. But it also creates a project that can unite the union, galvanizing support among constituencies that might not have supported Fain and Members United. For the Teamsters, the next step after settling their major contract at UPS is tackling their own existential threat: Amazon. The strategy there is less public than the UAW’s approach, quietly building organizing committees in key warehouses, while also pursuing a more public campaign to get Amazon drivers properly classified as Amazon employees, not independent contractors. Perhaps even more than the UPS contract, this will be the defining test of O’Brien’s leadership.

The challenges that both the UAW and IBT now face are daunting. But they have been daunting for a long time. The difference is that there are now viable paths to taking those challenges head-on. While the media headlines may focus on Fain and O’Brien’s new militant leadership, that leadership would not be possible without decades of patient rank-and-file organizing to set the stage. Whether they succeed in putting their unions on a more permanent path toward revitalization is still uncertain, but if they do, it could finally mark a turning point for the broader labor movement after decades of decline.