Ahead of French elections, vitriol and innuendo from National Rally candidates amplify doubts about how much the party of Marine Le Pen has truly evolved.

By Anthony Faiola and Annabelle Timsit

June 28, 2024

PARIS — French nationalist Marine Le Pen has executed one of the most extraordinary political rebrandings in the Western world. She has transformed the fringe neofascist party founded by her father into a mainstream political force with a shot at winning a majority and naming the next prime minister.

But as she and her deputy, Jordan Bardella, stand on the brink of what could be their greatest electoral triumph, innuendo, conspiracies and vitriol from National Rally candidates and supporters are amplifying doubts about how much a movement originally rooted in antisemitism and racism has truly evolved.

One candidate competing in the first round of the legislative assembly elections on Sunday suggested that a rival party was financed by Jews. Another claimed that some civilizations remain “below bestiality in the chain of evolution.” Yet another blamed a bedbug infestation in France on “the massive arrival from all the countries of Africa.” One more regularly pays tribute to the man who led the Nazi collaborators in World War II-era Vichy France.

France is rushing into a snap election with the far right ahead in the polls, followed by a left-wing bloc that some French Jews say harbors antisemites. (Video: Reuters)

French newspaper Libération has been compiling an “endless list” of National Rally candidates who have made or relayed “reprehensible remarks” online. Investigative outlet Mediapart counted 45 problematic profiles identified so far. Under the glare of media scrutiny, some candidates have deleted social media posts. Others appear content to let the record stand

Party leaders did not respond to requests for comment. In only a couple cases has the party taken disciplinary steps.

That may be because, like Italy’s Giorgia Meloni, Le Pen’s ability to expand her party’s reach requires a delicate balancing act. While they portray themselves as reformers and reject descriptions of their parties as extreme, they can cater to their hard-line base by giving space and oxygen to the unrepentant extremists in their ranks.

“If you take a look at who votes for them, I wouldn’t say all of them are racist or homophobic, but many of those who are vote for the National Rally,” said Vincent Martigny, a political scientist at the University of Nice.

The limits of Le Pen’s de-demonization project

Le Pen, 55, is widely credited with “de-demonizing” the movement launched in 1972 by her father, Jean Marie Le Pen, a serial polemicist who called the Nazi gas chambers a “detail” of history, suggested that somebody with AIDS should be treated “like a leper” and warned of a Muslim takeover of France.

Marine Le Pen purged Vichy remnants and Nazi apologists from the party, including booting out her father in 2015. She changed the name from National Front to National Rally in 2018 and set out to convince voters that it was a respectable party, ready to govern.

She has positioned herself as a defender of Israel, especially since the Oct. 7 Hamas attacks — while accusing the left of using the Israel-Gaza war as an opportunity to stigmatize Jews. She has stopped talking about leaving the European Union, muffled her admiration for Russian President Vladimir Putin and dropped a pledge to repeal same-sex marriage.

All the while, she has cultivated her protégé, Bardella, as the new youthful and broadly appealing face of the party.

But shifts in tone and optics have been more dramatic than any shifts in ideology.

MORE ON THE FRENCH ELECTIONS

Next

In France’s rebranded far right, flashes of antisemitism and racism persist

The French far right is leading in election polls. Here’s what to know.

French protesters decry far-right shift as snap election looms

Macron defends decision to call elections, slams possible alliance on the r...

Battered by far right, France’s Macron bets big on risky snap election

European Parliament tilts right; Macron calls snap elections in France

“They have new suits, very nice ties, but it’s still the same ideas in a more proper, more acceptable manner,” Martigny said.

Still at the core of the party’s platform is the notion of “national priority” — that “foreigners should have fewer rights than citizens even when they have equal qualifications,” said Jean-Yves Camus, director of the Observatory of Political Radicalism at the Jean Jaurès Institute. In practice, that means French nationals could have preferential access to public housing and other benefits.

National Rally has sought to woo voters by pledging to reduce fuel taxes and energy bills and protect French farmers. But its populist promises are targeted toward French citizens — in some cases even excluding dual nationals and “French people of foreign origin.”

The party continues to frame immigration as a security threat. Its leaders talk of “drastically reducing legal and illegal immigration and expelling foreign delinquents” as part of an effort to “put France in order.”

“Contrary to the caricature that is given of us, we have no problem with the fact that there may be foreigners in France, the only thing is that we demand that they behave correctly,” Le Pen said to French reporters during a recent campaign stop.

Anti-globalism, too, remains central to the National Rally program. Party leaders have backed off a pledge to pull France out of NATO’s strategic command, but called for limiting the kinds of weapons France sends to Ukraine. Conspiracy theories about Ukraine are regularly shared by National Rally candidates.

The party has benefited from a general shift to the right in Europe, especially on immigration. Positions that were once extreme are now in line with the thinking of a substantial portion of the electorate.

At the same time, in many parts of Europe, taboos have been falling away. Austria’s resurgent Freedom Party flirted with the center before once again committing itself to overt dog whistles and political references that hark back to the 1930s. Its chairman, Herbert Kickl, has repeatedly campaigned as the nation’s future “Volkskanzler,” or people’s chancellor — a former title of Adolf Hitler’s considered a loaded word in German.

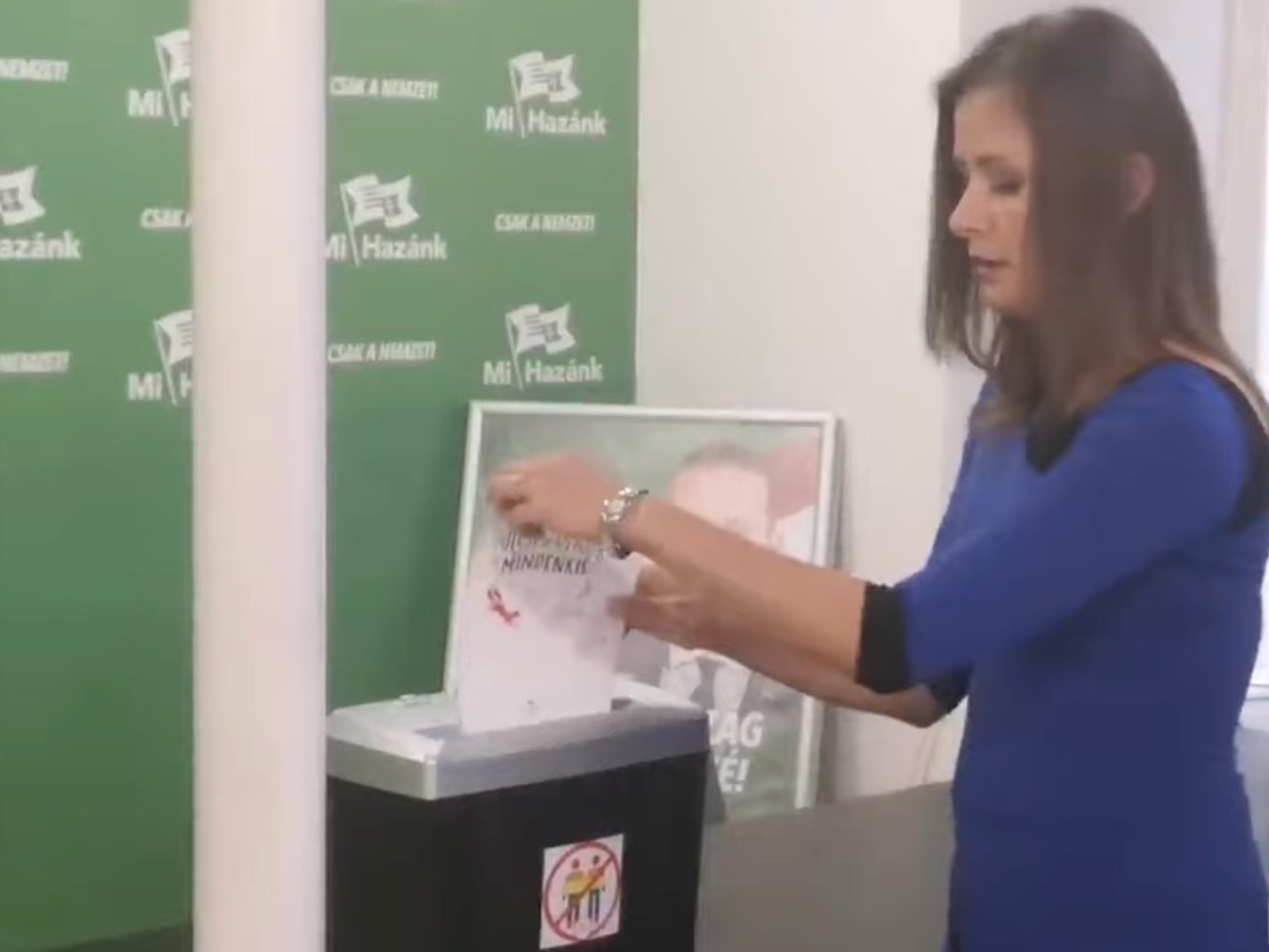

Few people fear a return of warmongering dictators in the heart of Europe. But there is concern about the spread of illiberal states like Viktor Orban’s Hungary, where the rule of law, political opposition, freedom of expression and foreign nonprofits have come under fire, while ties with Russia and China have been cultivated.

“I don’t trust [National Rally] to be democratic in the traditional, classic sense of the term,” said Dominique Moïsi, a noted French political scientist.

The unrepentant voices in the movement

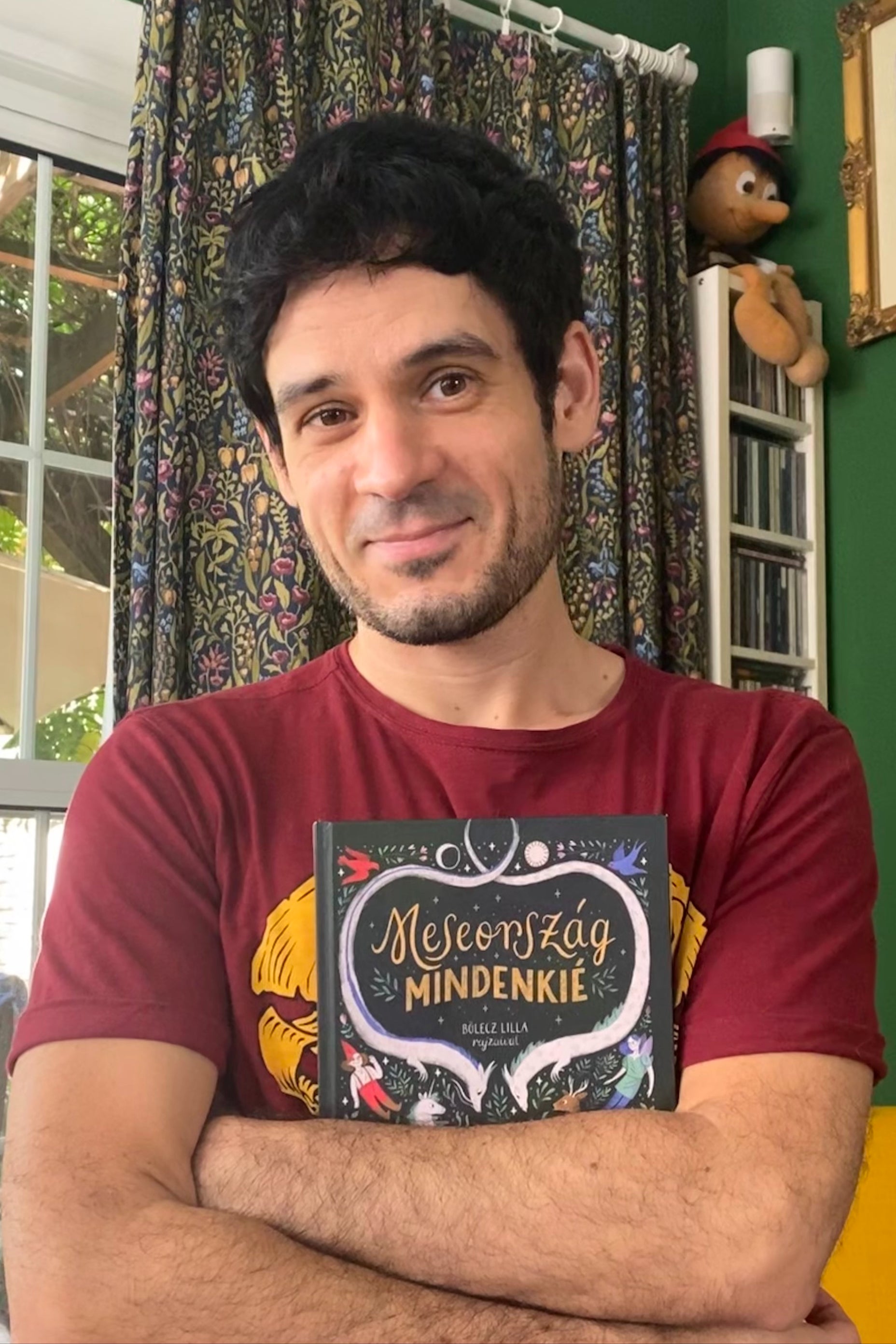

Glimmers of racism and antisemitism from National Rally candidates and supporters can bolster the impression that the movement has changed less than its leaders say.

There are more extreme voices in France than Le Pen’s. Yet, like Trumpism, LePénisme remains a safe harbor for anti-vaccine advocates, climate-change skeptics and Putin admirers. And as seen through social media posts and telling asides — as well as through homophobic attacks and racist tirades allegedly committed by Le Pen supporters — National Rally still provides a welcome home for vitriolic thought.

Marie-Christine Sorin, a National Rally candidate in southwestern France, posted on X in January that “not all civilizations are equal” and that some “have remained below bestiality in the chain of evolution.” She deleted the post after French newspaper Libération inquired about it, but defended the sentiment in a radio interview, saying she had been critiquing the treatment of women in Iran.

Sophie Dumont, a National Rally candidate in northeastern France, was spotlighted by Libération for a post implying that Jewish financing was behind Reconquest, a rival far-right party led by Eric Zemmour, who is Jewish. Zemmour’s adviser had said that the ritual slaughter of animals to make kosher and halal meat should not be banned in France. “The small gesture that betrays the origin of the funds that fuel Reconquest,” Dumont wrote in a now deleted comment.

Agnès Pageard, a National Rally candidate in Paris, has advocated for abolishing a law that makes it illegal to question the Holocaust and another that bans “incitement to hatred” against religious or racial groups. She responded to a social media post that alleged “collusion” among prominent Jewish people in France by recommending “reread Coston and Ratier” — two authors known for their antisemitic conspiracy theories.

Asked about seemingly antisemitic comments from candidates running in this election, National Rally frontman Bardella told French media that the process of selecting candidates for the surprise elections had necessarily been rushed, with “dozens, even hundreds of investitures … made in a few hours.” Never mind that some of the same candidates had run under the National Rally banner in past elections, too.

The notion that historically extreme parties have expelled their radical elements has helped their leaders gain global acceptance. Meloni’s Brothers of Italy party boasts a tricolor flame in its logo evoking a now-defunct movement made up of the political remnants of Benito Mussolini’s fascists. But Meloni has fiercely rejected the fascist label. At this month’s Group of Seven summit in southern Italy, where she was warmly greeted by world leaders including President Biden, she bristled at suggestions that her government and party were anything other than traditional conservatives.

While that summit was ongoing, Italy was rocked by the emergence of secret footage taken by a journalist who had infiltrated a Rome branch of the youth wing of Meloni’s party. “We’re Mussolini’s legionaries, and we’re not scared of death,” the group was filmed chanting. The footage contained other fascist songs and slogans, with members at one point shown giving the Roman salute while yelling “Sieg Heil!”

In a response to lawmakers, Meloni’s minister for parliamentary relations, Luca Ciriani, did not deny the acts occurred, nor did he condemn them. Rather, he described the footage as “decontextualized” images of “minors” that had been unfairly published without prior consent. It wasn’t until further revelations this week that senior party officials condemned the acts and called for swift punishment. Several involved youth league members also resigned.

After weeks of silence and mounting pressure, Meloni finally responded to the controversy late Thursday, calling racism and antisemitism “incompatible” with her party, while also criticizing the journalists involved in the secret report.

“We’re talking about an ongoing and deliberate apology of fascism,” said Matteo Orfini, an outraged lawmaker from the opposition Democratic Party.

In France, a different video sparked a scandal last week. A public broadcaster documented insults hurled at a Black woman, Divine Kinkela, by National Rally supporter neighbors in a town south of Paris. In released footage, one of the neighbors is heard saying that Kinkela should go to the “doghouse” and that they had left public housing “because of people like you.”

When asked about the report by news outlet La Voix du Nord, Le Pen said the neighbor’s invective was not racist.

Kate Brady in Berlin and Stefano Pitrelli in Rome contributed to this report.

By Anthony FaiolaAnthony Faiola is Rome Bureau Chief for The Washington Post. Since joining the paper in 1994, he has served as bureau chief in Miami, Berlin, London, Tokyo, Buenos Aires and New York and additionally worked as roving correspondent at large. Twitter

By Annabelle TimsitAnnabelle Timsit is a breaking news reporter for The Washington Post's London hub, covering news as it unfolds in the United States and around the world during the early morning hours in Washington. Twitter