There is A different reason to commemorate Nov 11 for anarchists, it was the day that the Haymarket Anarchists were hung in 1887. And like Sacco and Vanzetti they too were subject to nativist reactionary anti-immigrant hysteria and the anti-worker/anti-socialist fears of the Chicago ruling class.

Today the same hysteria is used to justify the so called War on Terror.

The labour and socialist movements globally usually commemorate their efforts to win the right to the eight hour day and the right to organize unions, on May Day.

The date of their state sanctioned assassination often gets overlooked. And that day was November 11, 1887.

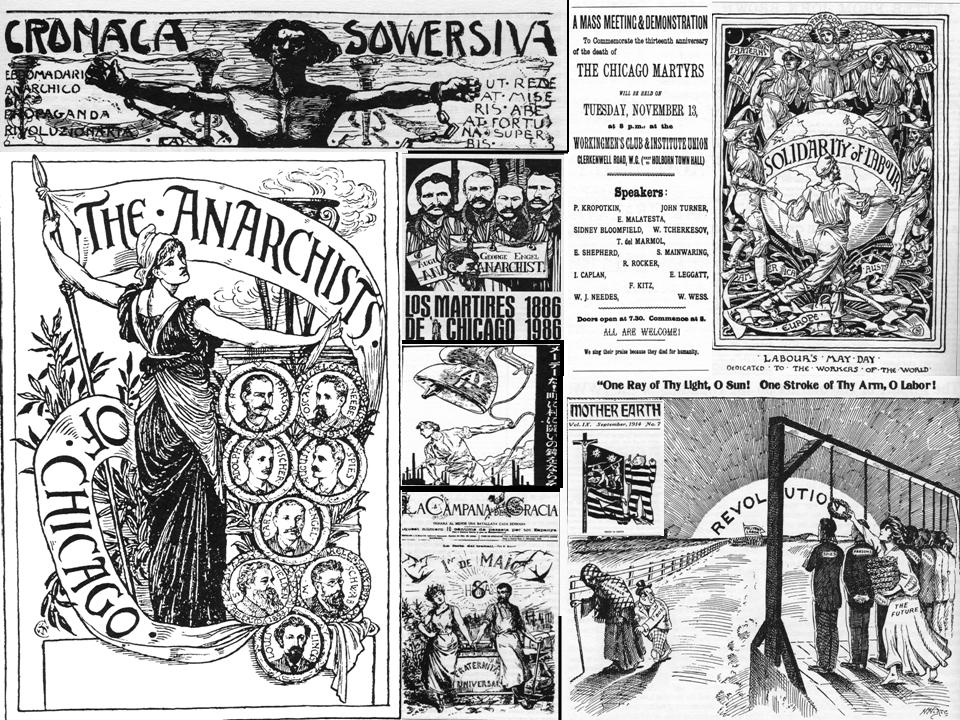

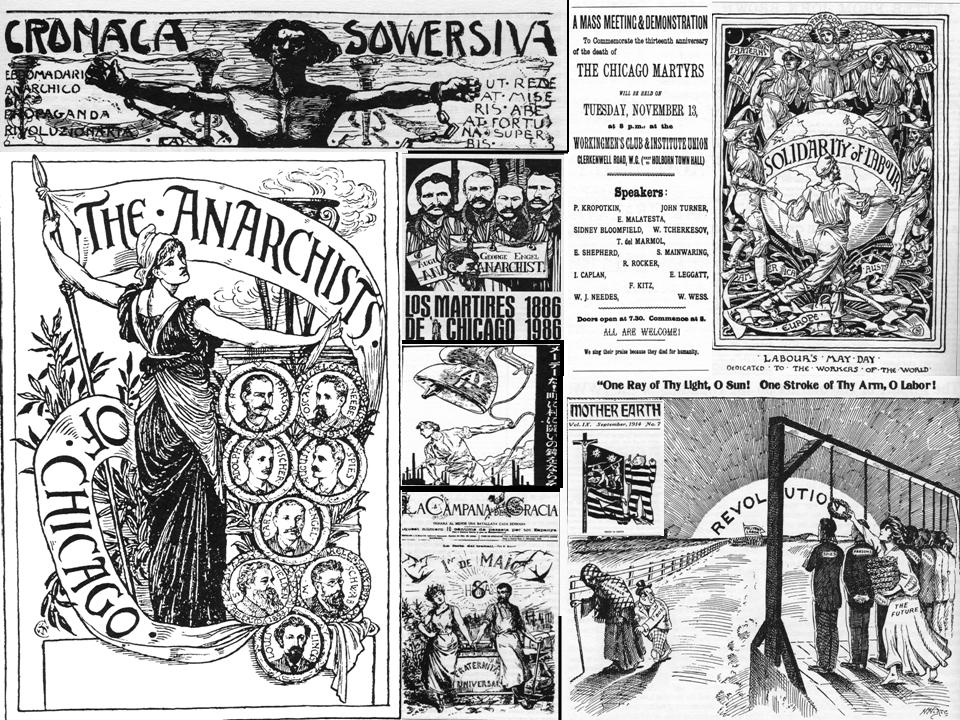

11 November 2007 is the 120th anniversary of the execution of the anarchist Haymarket martyrs: George Engel, Adolf Fischer, Albert Parsons and August Spies. Is it just ancient history to today's anarchists?

In November We Remember: The IWW & the Commemoration of Haymarket

By Franklin Rosemont

The 1886 Chicago Haymarket Bombing and the Rhetoric of Terrorism in AmericaThe Yale Journal of Criticism - Volume 15, Number 2, Fall 2002, pp. 315-344

The Johns Hopkins University Press

Jeffory A. Clymer - The 1886 Chicago Haymarket Bombing and the Rhetoric of Terrorism in America - The Yale Journal of Criticism 15:2 The Yale Journal of Criticism 15.2 (2002) 315-344

The 1886 Chicago Haymarket Bombing and the Rhetoric of Terrorism in America Jeffory A. Clymer [Figures] On 4 May 1886, about two thousand Chicagoans gathered at Haymarket Square to protest against the city's police, who had shot and killed at least two striking workers outside the McCormick reaper factory on the previous afternoon. The demonstration was peaceful, and only a few hundred people remained when, late in the evening, 170 Chicago policemen suddenly arrived and demanded that the protesters disperse. Nonplused by the anticlimactic arrival of the police at the close of a peaceful rally, Samuel Fielden, the evening's last speaker, pointed out the meeting's non-violent nature in response to the peremptory dispersal order. At this point in the exchange, someone tossed a dynamite bomb into the police ranks. The explosion immediately killed Officer Mathias Degan, wounded several others, and prompted a cacophony of gunfire, most of it from police pistols. In the chaos, the police shot several of their own officers as well as many of the fleeing civilians. While the number of dead among the police rose to seven over the next few days, the actual number of casualties among the protesters, like the bomb thrower's identity, was never determined.

READY FOR THE SCAFFOLD.

Brave While Being Shrouded - Good-by to Fielden and Schwab. The deputies who were with the four during the half-hour before the processions was formed were greatly impressed with their courage and fortitude. About this time Parsons received a telegram from San Francisco, signed "Four Citizens." It ran as follows:

Brave Parsons. Your name will live long after people will ask, "Who was Oglesby?"

Parsons took a pencil from his pocket and indorsed it on the back, "A. R. Parsons, Nov. 11, 1887." and handed it to Bailiff Wilson B. Brainerd, saying: "I will make you a present of this as a relic."

[four signature cards, clockwise]

Anarchy is Libery!

Adolph Fischer,

Cook Co. Jail,

Nov 11th '87.

A. R. Parsons

Liberty or Death

Nov. 11 1887

A Spies

G. Engel

11 November 1887

Execution of the Haymarket Anarchists

Illinois - The shadow of death, Will Chapin artist

1887, November 12 New York : Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper

BG D23/709

On 11 November 1887 the prison in Illinois is preparing for the execution of Parsons, Spies, Fischer, and Engel, the Haymarket anarchists. The Haymarket Affair started in May 1886 when a mass meeting was held in the Chicago Haymarket in the course of a strike for the eight-hour workday. When the police ordered the protest meeting to disperse, a bomb was thrown by an unknown person, killing several officers. Four anarchists were accused. The drawing in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper shows the scaffold, complete with a trap door. The balcony outside the cells was on the same level. At the back was a large box in which the hangman waited to release the rope for the trap door. At the execution Parsons could not be prevented from speaking his last words: "Let the voice of the people be heard!"

Fischer, Adolf (1859-1887)

|

| "This is the happiest moment of my life." |

| Adolf Fischer, a German anarchist, was a principal leader in the Chicago branch of the International Working People's Association, better known as the Black International. After organizing a walkout at the McCormick Harvester Works, gunfire broke out between anarchist supporters and police. Immediately, the Black International distributed a circular urging workers to "arm" themselves, assemble at Haymarket Square, and take "revenge." At the rally, Fischer and seven other anarchist leaders addressed the three thousand workers who showed up. After several hours of rather boring political oratory, the crowd became restless and most began to go home. Shortly thereafter, a police detachment arrived and ordered those who remained to disperse. The anarchist speakers objected, and someone tossed a bomb into the middle of the police ranks, killing one man and injuring about sixty others. The surviving police opened fire as did a number of anarchists and workers; another sixty men were injured or killed. The person who threw the bomb was never captured, but the anarchists who spoke at the rally were arrested and charged as accessories to murder. All were convicted. One was sentenced to fifteen years, the others to death. Fischer was hanged in November 1887. The Haymarket rioters have long-since become martyrs and heroes of international communism and anarchy, and leftist interpretations of the event abound.

|

| A similar scaffold pronouncement was made by George Eugel, another of the Haymarket anarchists, "Hurray for Anarchy! This is the happiest moment of my life." |

The Dramas of Haymarket, an online project produced by the Chicago Historical Society and Northwestern University. The Dramas of Haymarket examines selected materials from the Chicago Historical Society's Haymarket Affair Digital Collection, an electronic archive of CHS's extraordinary Haymarket holdings. The Dramas of Haymarket interprets these materials and places them in historical context, drawing on many other items from the Historical Society's extensive resources.

Eighty-five, bent and nearly blind, as poor as the day she arrived there more than a half-century earlier, Lucy Parsons addressed a rally in Chicago on November 11, 1937. It was the fiftieth anniversary of the day her husband, Albert Parsons, and three other anarchists were hanged by the State of Illinois for allegedly throwing a bomb in Haymarket Square at an open-air rally in May 1886, a rally called to condemn a brutal attack the previous day by police on striking workers at the McCormick Reaper Works. She was there to memorialize the Haymarket anarchists and to cry out against a more recent act of deadly violence, the "Memorial Day Massacre" that spring, when Chicago police shot ten men in the back who had gathered, along with thousands of others, to demand union recognition at Republic Steel, a bitterly antiunion corporation. For Lucy nothing had changed. Such savagery would continue, she told her listeners, until capitalism was overthrown. That was the nub of a conviction that had inspired her, her husband, their comrades and untold numbers of others all across late nineteenth-century America. They were alive in an age that, with the singular exception of the Civil War, was arguably the most protracted period of social violence in the country's history; one might even call it an undeclared second civil war following hard on the heels of the first.

Learning From the Children Of the '80s -- the 1880sAs soon as I began to read about events that happened outside of my lifetime, I learned about an era of essential revolution that put the 1960s to shame.

Excerpted from James Green, "Remembering Haymarket: Chicago's Labor Martyrs and Their Legacy," in Taking History to Heart: The Power of the Past in Building Social Movements (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2000)

Excerpt from the Prologue to Death in the Haymarket by James Green, Pantheon Books, 2006 Copyright James Green

The Globalization of Memory: The Enduring Memory of Chicago’s Haymarket Martyrs around the World by James Green

The Origins of May Day: A Story of Chicago, the First Labor Movement and the Bombing That Divided Gilded Age America

We look at the origins of May Day with James Green, a professor of history and labor studies at the University of Massachusetts and the author of "Death in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, the First Labor Movement and the Bombing That Divided Gilded Age America."

REMEMBERING HAYMARKET: May Day and the fight for eight hoursInterview with James Green, author of Death in the Haymarket Radicals! An Analysis of The New York Times Articles On The Haymarket Affair

NYT Archival facsimiles:

JUDGE GARY TO TRY LUETGERT.; He Presided at the Haymarket Square Anarchists' Trials in Chicago

THE CHICAGO ANARCHISTS.; COOK COUNTY GRAND JURY PURSUING THEIR INVESTIGATION.

William Dean Howells (1837-1920), author, editor, and criticAfter the execution of the Haymarket radicals in 1887, which he risked his reputation to protest, Howells became increasingly concerned with social issues, as seen in stories such as "Editha" (1905) and novels concerned with race (An Imperative Duty, 1892), the problems of labor (Annie Kilburn, 1888), and professions for women (The Coast of Bohemia, 1893).

Widely acknowledged during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as the "Dean of American Letters," Howells was elected the first president of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1908, which instituted its Howells Medal for Fiction in 1915. By the time of his death from pneumonia on 11 May 1920, Howells was still respected for his position in American literature. However, his later novels did not achieve the success of his early realistic work, and later authors such as Sinclair Lewis denounced Howells's fiction and his influence as being too genteel to represent the real America.

Kristin Boudreau, "Elegies for the Haymarket Anarchists," AL77 (June 2005), 319-347.

The execution on 11 November 1887 of four of the eight men convicted for their parts in the Chicago Haymarket bombing the previous year led to a deluge of public responses. Though most of the first ones denounced the eight as "anarchists," in the following months daily newspaper "swelled"with elegiac poems memorizing the men. Howells, no longer a poet but now a prominent novelist, did not contribute directly to this outpouring, but he lent his support for the poems that spoke to the masses on a topic of such important social concern, and he also used the newspaper on the day after the execution when he wrote in a letter to the editor of the New York Tribunethat the multiple execution was an "'atrocious and irreparable wrong'" (342).

Haymarket Photos - Rioting #1 -

Rioting #2 -

Counsel for the Defense -

Prosecuting Attorneys -

The Jury -

The Haymarket Anarchists -

Panic after Bomb -

Haymarket Martyrs -

Haymarket 5 Memorial (top) -

Large Haymarket 5 Memorial (top) -

Haymarket 5 Memorial (bottom) -

Large Haymarket 5 Memorial (bottom) -

Haymarket Memorial (top) -

Haymarket Memorial (bottom) -

Haymarket Memorial (b/w) -

Small Martyrs #1 -

Small Martyrs #2 -

Police Monument Distant -

Police Monument Close Up -

Police Monument Side View -

Police Monument Plaque -

Haymarket Square Today -

From the home of the labor movement to...

The Limits of Analogy: José Martí and the Haymarket Martyrs

The Limits of Analogy: José Martí and the Haymarket Martyrs

For Martí, the execution of the Haymarket anarchists marks the site of a national catastrophe that belies the myth of North American democracy. For years, in his critique of immigrants and radical ideologies in the labor movement, Martí had upheld the geopolitical teleology that stated that the U.S. was further along the path of liberty than Europe, which was weighed down by age-old divisions between rich and poor. Now, Martí collapsed the distinction and declared that the U.S. was no different than a monarchy (“Un drama terrible,” 796). In his initial reactions to Haymarket, Martí had celebrated the heroism of the police and demonized the European anarchists in terms similar to those found in the mainstream U.S. press. In “Un drama terrible,” however, he retells the story of what happened on May fourth in a way that was much more sympathetic to workers and anarchists. He indicts the police, the national media and the justice system for their lies and corruption. If before he had referred to the anarchists as beasts, now it was the Republic as a whole that has become savage like a wolf (795). Martí’s newfound solidarity with the working class, and his sympathetic representation of the anarchists he had previously rejected, results in a powerful identification with the working class, where a new community emerges out of the ruins of the Haymarket Affair.In America, the Haymarket incident and the assassination of President McKinley had a similar effect. The Haymarket incident occurred in 1886, in Chicago which was a stronghold of communist anarchism. A group of anarchists, most prominently Albert Parsons, held an open door labor meeting; as it began to break up police converged on the peaceful crowd. A bomb was thrown at the police who opened fire on the crowd. Seven demonstrably innocent men were arrested and tried: one committed suicide, four were hanged, two were subsequently pardoned. I don't have time to go into the Haymarket incident other than to point out three things: first, the men involved in the Haymarket affair were communist anarchists who openly advocated violence, which is not to say they were guilty of any crime or to reduce their status as anarchist martyrs. Second, the Haymarket incident and the public furor that followed it changed the public perception of anarchism by associating it firmly with violence.

Third, individualist anarchists did not enthusiastically support the Haymarket martyrs. For example, although Benjamin Tucker condemned the State and recognized it as the true villain of the event, he criticized the Haymarket Seven for consciously promoting violence and he was reluctant to raise them to the status of anarchist heroes. In the July 31, 1886 issue of Liberty, he wrote: "It is because peaceful agitation and passive resistance are weapons more deadly to tyranny than any others that I uphold them ... brute force strengthens tyranny... War and authority are companions; peace and liberty are companions... The Chicago Communists I look upon as brave and earnest men and women. That does not prevent them from being equally mistaken." This reluctance on the part of individualist anarchists, whose stronghold was Boston, outraged other anarchists who began to refer to anyone who criticized the Haymarket martyrs as 'a Boston anarchist' regardless of where the critic lived. (Tucker's Liberty was published from Boston.)

The assassination of President McKinley in 1901 by a self- professed anarchist who claimed to have been inspired by hearing Emma Goldman speak almost destroyed the anarchist movement. The deportations and hideous laws that followed were the most obvious repercussions. But perhaps as importantly, it absolutely cemented the association between violence and anarchism, all forms of anarchism. The movement declined sharply past the turn of the century. And individualist anarchism virtually died in 1908 when the offices of Tucker's Liberty and bookstore burnt to the ground.

The Psychology of Political Violence

Emma Goldman

That every act of political violence should nowadays be attributed to Anarchists is not at all surprising. Yet it is a fact known to almost everyone familiar with the Anarchist movement that a great number of acts, for which Anarchists had to suffer, either originated with the capitalist press or were instigated, if not directly perpetrated, by the police.

For a number of years acts of violence had been committed in Spain, for which the Anarchists were held responsible, hounded like wild beasts, and thrown into prison. Later it was disclosed that the perpetrators of these acts were not Anarchists, but members of the police department. The scandal became so widespread that the conservative Spanish papers demanded the apprehension and punishment of the gang-leader, Juan Rull, who was subsequently condemned to death and executed. The sensational evidence, brought to light during the trial, forced Police Inspector Momento to exonerate completely the Anarchists from any connection with the acts committed during a long period. This resulted in the dismissal of a number of police officials, among them Inspector Tressols, who, in revenge, disclosed the fact that behind the gang of police bomb throwers were others of far higher position, who provided them with funds and protected them.

This is one of the many striking examples of how Anarchist conspiracies are manufactured.

That the American police can perjure themselves with the same ease, that they are just as merciless, just as brutal and cunning as their European colleagues, has been proven on more than one occasion. We need only recall the tragedy of the eleventh of November, 1887, known as the Haymarket Riot.

No one who is at all familiar with the case can possibly doubt that the Anarchists, judicially murdered in Chicago, died as victims of a lying, blood-thirsty press and of a cruel police conspiracy. Has not Judge Gary himself said: "Not because you have caused the Haymarket bomb, but because you are Anarchists, you are on trial."

The impartial and thorough analysis by Governor Altgeld of that blotch on the American escutcheon verified the brutal frankness of Judge Gary. It was this that induced Altgeld to pardon the three Anarchists, thereby earning the lasting esteem of every liberty-loving man and woman in the world.

When we approach the tragedy of September sixth, 1901, we are confronted by one of the most striking examples of how little social theories are responsible for an act of political violence. "Leon Czolgosz, an Anarchist, incited to commit the act by Emma Goldman." To be sure, has she not incited violence even before her birth, and will she not continue to do so beyond death? Everything is possible with the Anarchists.

Today, even, nine years after the tragedy, after it was proven a hundred times that Emma Goldman had nothing to do with the event, that no evidence whatsoever exists to indicate that Czolgosz ever called himself an Anarchist, we are confronted with the same lie, fabricated by the police and perpetuated by the press. No living soul ever heard Czolgosz make that statement, nor is there a single written word to prove that the boy ever breathed the accusation. Nothing but ignorance and insane hysteria, which have never yet been able to solve the simplest problem of cause and effect.

The Dawn-Light of Anarchy

by Voltairine de Cleyre

The events of May 4, 1886 were a major influence on the oratory of Voltairine de Cleyre. Following the execution of the Haymarket Martyrs on November 11, 1887, she gave an annual address to commemorate the date of their sacrifice. The following memorial speech was first delivered in Chicago on November 11, 1901. It was subsequently published in Free Society, a Chicago periodical, November 24, 1901. It is reprinted, along with her other Haymarket Memorial speeches, in The First Mayday: The Haymarket Speeches 1895-1910 (Cienfuegos Press, Over-the-water, Sanday, Orkney, KWI7 2BL, UK), 1980.

Let me begin my address with a confession. I make it sorrowfully and with self-disgust; but in the presence of great sacrifice we learn humility, and if my comrades could give their lives for their belief, why, let me give my pride. Yet I would not give it, for personal utterance is of trifling importance, were it not that I think at this particular season it will encourage those of our sympathizers whom the recent outburst of savagery may have disheartened, and perhaps lead some who are standing where I once stood to do as I did later.

This is my confession: Fifteen years ago last May when the echoes of the Haymarket bomb rolled through the little Michigan village where I then lived, I, like the rest of the credulous and brutal, read one lying newspaper headline, “Anarchists throw a bomb in a crowd in the Haymarket in Chicago”, and immediately cried out, “They ought to be hanged!” This, though I had never believed in capital punishment for ordinary criminals. For that ignorant, outrageous, blood-thirsty sentence I shall never forgive myself, though I know the dead men would have forgiven me, though I know those who loved them forgive me. But my own voice, as it sounded that night, will sound so in my ears till I die — a bitter reproach and shame. What had I done? Credited the first wild rumor of an event of which I knew nothing, and, in my mind, sent men to the gallows without asking one word of defense! In one wild, unbalanced moment threw away the sympathies of a lifetime, and became an executioner at heart. And what I did that night millions did, and what I said millions said. I have only one word of extenuation for myself and all those people — ignorance. I did not know what Anarchism was. I had never seen the word used save in histories, and there it was always synonymous with social confusion and murder. I believed the newspapers. I thought those men had thrown that bomb, unprovoked, into a mass of men and women, from a wicked delight in killing. And so thought all those millions of others. But out of those millions there were some few thousand — I am glad I was one of them — who did not let the matter rest there.

I know not what resurrection of human decency first stirred within me after that — whether it was an intellectual suspicion that maybe I did not know all the truth of the case and could not believe the newspapers, or whether it was the old strong undercurrent of sympathy which often prompts the heart to go out to the accused, without a reason; but this I do know, that though I was no Anarchist at the time of the execution, it was long and long before that, that I came to the conclusion that the accusation was false, the trial a farce, that there was no warrant either in justice or in law for their conviction; and that the hanging, if hanging there should be, would be the act of a society composed of people who had said what I said on the first night, and who had kept their eyes and ears fast shut ever since, determined to see nothing and to know nothing but rage and vengeance. Till the very end I hoped that mercy might intervene, though justice did not; and from the hour I knew neither would nor ever could again, I distrusted law and lawyers, judges and governors alike. And my whole being cried out to know what it was these men had stood for, and why they were hanged, seeing it was not proven they knew anything about the throwing of the bomb.

Little by little, here and there, I came to know that what they had stood for was a very high and noble ideal of human life, and what they were hanged for was preaching it to the common people — the common people who were as ready to hang them, in their ignorance, as the court and the prosecutor were in their malice! Little by little I came to know that these were men who had a clearer vision of human right than most of their fellows; and who, being moved by deep social sympathies, wished to share their vision with their fellows, and so proclaimed it in the market-place. Little by little I realized that the misery, the pathetic submission, the awful degradation of the workers, which from the time I was old enough to begin to think had borne heavily on my heart (as they must bear upon all who have hearts to feel at all), had smitten theirs more deeply still — so deeply that they knew no rest save in seeking a way out — and that was more than I had ever had the sense to conceive. For me there had never been a hope there should be no more rich and poor; but a vague idea that there might not be so rich and so poor, if the workingmen by combining could exact a little better wages, and make their hours a little shorter. It was the message of these men (and their death swept that message far out into ears that would never have heard their living voices) that all such little dreams are folly. That not in demanding little, not in striking for an hour less, not in mountain labor to bring forth mice, can any lasting alleviation come; but in demanding much — all — in a bold self-assertion of the worker to toil any hours he finds sufficient, not that another finds for him — here is where the way out lies. That message, and the message of others, whose works, associated with theirs, their death drew to my notice, took me up, as it were, upon a mighty hill, wherefrom I saw the roofs of the workshops of the little world. I saw the machines, the things that men had made to ease their burden, the wonderful things, the iron genii; I saw them set their iron teeth in the living flesh of the men who made them; I saw the maimed and crippled stumps of men go limping away into the night that engulfs the poor, perhaps to be thrown up in the flotsam and jetsam of beggary for a time, perhaps to suicide in some dim corner where the black surge throws its slime.

I saw the rose fire of the furnace shining on the blanched face of the man who tended it, and knew surely as I knew anything in life, that never would a free man feed his blood to the fire like that.

I saw swarthy bodies, all mangled and crushed, borne from the mouths of the mines to be stowed away in a grave hardly less narrow and dark than that in which the living form had crouched ten, twelve, fourteen hours a day; and I knew that in order that I might be warm — I, and you, and those others who never do any dirty work — those men had slaved away in those black graves, and been crushed to death at last.

I saw beside city streets great heaps of horrible colored earth, and down at the bottom of the trench from which it was thrown, so far down that nothing else was visible, bright gleaming eyes, like a wild animal’s hunted into its hole. And I knew that free men never chose to labor there, with pick and shovel in that foul, sewage-soaked earth, in that narrow trench, in that deadly sewer gas ten, eight, even six hours a day. Only slaves would do it. I saw deep down in the hull of the ocean liner the men who shoveled the coal burned and seared like paper before the grate; and I knew that “the record” of the beautiful monster, and the pleasure of the ladies who laughed on the deck, were paid for with these withered bodies and souls.

I saw the scavenger carts go up and down, drawn by sad brutes, driven by sadder ones; for never a man, a man in full possession of his selfhood, would freely choose to spend all his days in the nauseating stench that forces him to swill alcohol to neutralize it.

And I saw in the lead works how men were poisoned; and in the sugar refineries how they went insane; and in the factories how they lost their decency; and in the stores how they learned to lie; and I knew it was slavery made them do all this. I knew the Anarchists were right — the whole thing must be changed, the whole thing was wrong — the whole system of production and distribution, the whole ideal of life.

And I questioned the government then; they had taught me to question it. What have you done — you the keepers of the Declaration and the Constitution — what have you done about all this? What have you done to preserve the conditions of freedom to the people?

Lied, deceived, fooled, tricked, bought and sold and got gain! You have sold away the land, that you had no right to sell. You have murdered the aboriginal people, that you might seize the land in the name of the white race, and then steal it away from them again, to be again sold by a second and a third robber. And that buying and selling of the land has driven the people off the healthy earth and away from the clean air into these rot-heaps of humanity called cities, where every filthy thing is done, and filthy labor breeds filthy bodies and filthy souls. Our boys are decayed with vice before they come to manhood; our girls — ah, well might john Harvey write:

Another begetteth a daughter white and gold,

She looks into the meadow land water, and the world

Knows her no more; they have sought her field and fold

But the City, the City hath bought her,

It hath sold

Her piecemeal, to students, rats, and reek of the graveyard mold.

You have done this thing, gentlemen who engineer the government; and not only have you caused this ruin to come upon others; you yourself are rotten with debauchery. You exist for the purpose of granting privileges to whoever can pay most for you, and so limiting the freedom of men to employ themselves that they must sell themselves into this frightful slavery or become tramps, beggars, thieves, prostitutes, and murderers. And when you have done all this, what then do you do to them, these creatures of your own making? You, who have set them the example in every villainy? Do you then relent, and remembering the words of the great religious teacher to whom most of you offer lip service on the officially religious day, do you go to these poor, broken, wretched creatures and love them? Love them and help them, to teach them to be better? No: you build prisons high and strong, and there you beat, and starve, and hang, finding by the working of your system human beings so unutterably degraded that they are willing to kill whomsoever they are told to kill at so much monthly salary.

This is what the government is, has always been, the creator and defender of privilege; the organization of oppression and revenge. To hope that it can ever become anything else is the vainest of delusions. They tell you that Anarchy, the dream of social order without government, is a wild fancy. The wildest dream that ever entered the heart of man is the dream that mankind can ever help itself through an appeal to law, or to come to any order that will not result in slavery wherein there is any excuse for government.

It was for telling the people this that these five men were killed. For telling the people that the only way to get out of their misery was first to learn what their rights upon this earth were — freedom to use the land and all within it and all the tools of production — and then to stand together and take them, themselves, and not to appeal to the jugglers of the law. Abolish the law — that is abolish privilege — and crime will abolish itself.

They will tell you that these men were hanged for advocating force. What! These creatures who drill men in the science of killing, who put guns and clubs in hands they train to shoot and strike, who hail with delight the latest inventions in explosives, who exult in the machine that can kill the most with the least expenditure of energy, who declare a war of extermination upon people who do not want their civilization, who ravish, and burn, and garrote, and guillotine, and hang, and electrocute — they have the impertinence to talk about the unrighteousness of force! True, these men did advocate the right to resist invasion by force. You will find scarcely one in a thousand who does not believe in that right. The one will be either a real Christian or a non-resistant Anarchist. It will not be a believer in the State. Nor, no; it was not for advocating forcible resistance on principle, but for advocating forcible resistance to their tyrannies, and for advocating a society which would forever make an end of riches and poverty, of governors and governed.

The spirit of revenge, which is always stupid, accomplished its brutal act. Had it lifted its eyes from its work, it might have seen in the background of the scaffold that bleak November morning the dawn-light of Anarchy whiten across the world.

So it came first — a gleam of hope to the proletaire, a summons to rise and shake off his material bondage. But steadily, steadily, the light has grown, as year by year the scientist, the literary genius, the artist, and the moral teacher, have brought to it the tribute of their best work, their unpaid work, the work they did for love. Today it means not only material emancipation, too; it comes as the summing up of all those lines of thought and action which for three hundred years have been making towards freedom; it means fullness of being, the free life.

And I saw it boldly, notwithstanding the recent outburst of condemnation, notwithstanding the cry of lynch, burn, shoot, imprison, deport, and the Scarlet Letter A to be branded low down upon the forehead, and the latest excuse for that fond esthetic decoration “the button”, that for two thousand years no idea has so stirred the world as this — none which had such living power to break down the barriers of race and degree, to attract prince and proletaire, poet and mechanic, Quaker and Revolutionist. No other ideal but the free life is strong enough to touch the man whose infinite pity and understanding goes alike to the hypocrite priest and the victim of Siberian whips; the loving rebel who stepped from his title and his wealth to labor with all the laboring earth; the sweet strong singer who sang No master, high or low; the lover who does not measure his love nor reckon on return; the self-centered one who “will not rule, but also will not ruled be”; the philosopher who chanted the Over-man; the devoted woman of the people; aye, and these too — these rebellious flashes from the vast cloud-hung ominous obscurity of the anonymous, these souls whom governmental and capitalistic brutality has whipped and goaded and stung to blind rage and bitterness, these mad young lions of revolt, these Winkelrieds who offer their hearts to the spears.

“A great poet and one of the finest types of Anarchist that ever lived.”

- Emma Goldman

David Edelstadt was born on 9 May 1866 at Kaluga in Russia. He was deeply affected by the life of his father,enrolled by force in the Tsar’s army for 25 years. This type of practice carried out by the Russian army was often used against Jews. Whilst Russian was his mother tongue, Yiddish was his language of communication and propaganda. He used it from his emigration to the United States in 1882.

He participated in the first Jewish anarchist group in New York, The Pioneers of Liberty ( Pionire der Frayhayt). The framing of the Chicago Haymarket Anarchists had led to its formation. The first dozen workers who set up the group were joined by Edelstadt and other gifted writers and speakers – Saul Yanovsky, Roman Lewis, Hillel

Solotaroff, Moshe Katz, JA Maryson.

All in their 20s, this group “displayed, apart from unusual literary and oratorical skills, a vigour and dynamic energy that made a powerful impression on the immigrants of the Lower East Side, the predominantly Jewish quarter of New York in which the Pioneers of Liberty were located” (Paul Avrich).

Edelstadt and the others held meetings, sponsored rallies and raised funds to help the Haymarket Chicago anarchists being framed for murder. They organised a ball on the Lower East Side which raised $100 (quite a large sum then), which was sent to the families of the defendants. They began to spread anarchist propaganda among the Jewish immigrants, who were arriving in the States in increasing numbers. They set up a club on brought out literature in Yiddish, including a pamphlet on the Haymarket case.

"Hurrah for anarchy!" - Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Scientific Basis

Albert R. Parsons

"Hurrah for anarchy!" These were the last words of two of the five anarchists hung by the state in 1887. They were murdered by the state because of their revolutionary politics, union organising and their role at the head of the strike movement for the eight hour day which started on May 1st, 1886. The nominal reason for their trial and murder was the bomb explosion which killed one of the policemen sent to break up an anarchist meeting on May 4th. The meeting was protesting the killing of a picket the day before by the police.

The real reason for their deaths was their anarchism and role in the eight-hour day strikes which were rocking America. "Anarchism is on trail," proclaimed the state and a packed jury and biased judge ensured their conviction. Four anarchists were hung on November 11th, 1887 and another cheated the hangman by committing suicide. Three others has their sentences commuted to life imprisonment. Six years later, the new Governor of Illinois pardoned the Martyrs because of their obvious innocence, saying "the trail was not fair." By then, the May 1st had been adopted as international workers' day to commemorate the "Martyrdom of the Chicago Eight". May Day had been born.

While the Haymarket events radicalised a whole generation of people to become anarchists, including Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, very little is known about the politics of the Chicago Anarchists. This is, in part, deliberate. How many times have Marxists talked about May Day and failed to mention the anarchism of the "labour leaders" involved? Or that the anarchists were union activists? In anarchist circles, there is little material written by the Martyrs available. Luckily, this has changed with the republication of Albert Parsons' book "Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Scientific Basis."

Albert Parsons was the only native born American among the Martyrs. A former Confederate soldier, he became a socialist after the civil war. Soon seeing the pointlessness of the ballot box, he, like the rest of the Martyrs, turned to anarchism. Its direct action and union organising proving to be far more effective in the class war than the socialist strategy. He complied this book while in prison waiting for execution in order to explain the ideas of anarchism. And it succeeds.

Thus we find Albert Parsons arguing that "anarchy is the social administration of all affairs by the people themselves; that is to say, self-government, individual liberty . . . the people . . . participate equally in governing themselves . . . the people voluntarily associate or freely withdraw from association; instead of being bossed or driven as now . . . The workshops will drop into the hands of the workers, the mines will fall to the mines, and the land and all other things will be controlled by those who posses and use them." For "wealth is power . . . The chattel slave of the past -- the wage slave of today; what is the difference? The master selected under chattel slavery his own slaves. Under the wage slavery system the wage slave selects his master" and he refused "equally to be a slave or the owner of slaves."

Modern anti-capitalists have raised the slogan "the world is not for sale" and would, undoubtedly, agree with Parsons when he argued that the "existing economic system has placed on the markets for sale man's natural rights . . . A freeman is not for sale or for hire" While nowadays wage labour is commonplace, in 1880s America it was different. The first few generations of workers had just become wage slaves and hated it. Parsons spoke for them (and us!): "the wage system of labour is a despotism. It is coercive and arbitrary. It compels the wage worker, under a penalty of hunger, misery and distress . . . to obey the dictation of the employer. The individuality of the wage-worker . . . is destroyed by the wage-system. . . . Political liberty is possessed by those only who also possess economic liberty. The wage-system is the economic servitude of the workers."

Yet the Martyrs were not just critics. They constantly stressed the positive and constructive aspects of their ideas. Michael Schwab, for example, argued that "Socialism . . .means that land and machinery shall be held in common by the people . . . Four hours' work would suffice to produce all that . . . is necessary for a comfortable living. Time would be left to cultivate the mind, and to further science and act . . . Some say it is un-American! Well, then, is it American to let people starve and die in ignorance? Is exploitation and robbery of the poor, American?" No, this was not meant to be a trick question!

The Martyrs had, originally, been Marxists and this can be seen from some of the terminology used by the eight. Parsons quotes extensively from Marx's "Wage Labour and Capitol" as well as the "Communist Manifesto" when he discusses the development of capitalism in the United States and Europe. However, while they agreed with Marx's economic analysis of the system they rejected his ideas on how to get there. "Anarchism and socialism," wrote George Engell, "differ only in their tactics . . . Believe no more in the ballot, and use all other means at your command." Instead of elections they followed Bakunin and saw the labour movement as both the means of achieving anarchy and the framework of the free society. As Lucy Parsons (the wife of Albert) put it "we hold that the granges, trade-unions, Knights of Labour assemblies, etc., are the embryonic groups of the ideal anarchistic society . . . We ask for the decentralisation of power." For the Martyrs, working class people had to liberate themselves by their own efforts and using their own organisations. This is just as true today and is their most important legacy.

They equally rejected the false notion of a "workers' state." "Anarchists," wrote Adolph Fischer, "hold that it is the natural right of every member of the human family to control themselves. If a centralised power -- government -- is ruling the mass of people . . . it is enslaving them." However, "every anarchist is a socialist but every socialist is not necessarily an anarchist . . . the communistic anarchists demand the abolition of political authority, the state . . . we advocate the communistic or co-operative methods of production." In the words of August Spies: "You may pronounce the sentence upon me, honourable judge, but let the world know that in A.D. 1886, in the State of Illinois, eight men were sentenced to death because they believed in a better future; because they had not lost their faith in the ultimate victory of liberty and justice!"

The passion for justice and freedom which inspired the Martyrs comes through. They are utterly unapologetic for their activism and anarchism: "I say to you: 'I despise you. I despise your order; your laws, your force-propped authority.' HANG ME FOR IT!" (Louis Lingg). Equally, they did not try and hide their revolutionary ideas. They knew they faced class justice and knew that "only by force of arms can the wage slaves make their way out of capitalistic bondage" (Adolph Fischer). Yet the injustice meted out to the Chicago Eight failed to crush the labour or anarchist movements for obvious reasons. They were born from resisting capitalism and would remain as long as it does. As August Spies put it:

"But, if you think that by hanging us, you can stamp out the labour movement -- the movement from which the downtrodden millions, the millions who toil and live in want and misery -- the wage slaves -- expect salvation -- if that is your opinion, then hang us! Here you tread upon a spark, but there, and there; and behind you, and in front of you, and everywhere, flames will blaze up. It is a subterranean fire. You cannot put it out."

Unfortunately, the new edition lacks a modern introduction which could have summarised the events and their aftermath for a reader who is unaware of them. However, for someone who knows the general history of the Haymarket events and wants to read what the Martyrs thought and did then this book is essential reading. Moreover, it includes essays by Elisee Reclus, Dyer D Lum and C.L. James (anarchists whose works are extremely rare to find these days) as well as the original two articles by Kropotkin which became the pamphlet "Anarchist Communism: Its basis and principles."

As such, it is a well rounded account of the ideas of the Chicago anarchists, why they became anarchists and their role in the events that created May Day. While undoubtedly dated, the book is essential reading for those interested in the ideas and history of anarchism. The Martyrs accounts of their lives and activism show why people have died fighting for a better future, for anarchy, far better than any pseudo-neutral history. As Michael Schwab wrote: "Anarchy is a dream, but only in the present. It will be realised." This book should inspire others to fight to realise that dream.

"Hurrah for anarchy!" - Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Scientific Basis Albert R. Parsons University Press of the Pacific Honolulu, Hawaii ISBN: 1-4102-0496-5

The Accused, the accusers: the famous speeches of the eight Chicago anarchists in court when asked if they had anything to say why sentence should not be passed upon them. On October 7th, 8th and 9th, 1886, Chicago, Illinois

Contains addresses by August Spies, Michel Schwab, Oscar Neebe, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg, George Engel, Samuel Fielden, and Albert R. Parsons

Last Words to His Wife

The Chicago radicals convicted of the infamous May 4, 1886 Haymarket Square bombing in which one policeman was killed remained openly defiant to the end. In his final letter to his wife, written August 20, 1886 from the Cook County “Bastille” (jail), convicted Haymarket bombing participant Albert R. Parsons, an Alabama-born printer, admitted that the verdict would cheer “the hearts of tyrants,” but still optimistically predicted that “our doom to death is the handwriting on the wall, foretelling the downfall of hate, malice, hypocrisy, judicial murder, oppression, and the domination of man over his fellow-man.”

Cook County Bastille, Cell No. 29,

Chicago, August 20, 1886.

My Darling Wife:

Our verdict this morning cheers the hearts of tyrants throughout the world, and the result will be celebrated by King Capital in its drunken feast of flowing wine from Chicago to St. Petersburg. Nevertheless, our doom to death is the handwriting on the wall, foretelling the downfall of hate, malice, hypocrisy, judicial murder, oppression, and the domination of man over his fellowman. The oppressed of earth are writhing in their legal chains. The giant Labor is awakening. The masses, aroused from their stupor, will snap their petty chains like reeds in the whirlwind.

We are all creatures of circumstance; we are what we have been made to be. This truth is becoming clearer day by day.

There was no evidence that any one of the eight doomed men knew of, or advised, or abetted the Haymarket tragedy. But what does that matter? The privileged class demands a victim, and we are offered a sacrifice to appease the hungry yells of an infuriated mob of millionaires who will be contented with nothing less than our lives. Monopoly triumphs! Labor in chains ascends the scaffold for having dared to cry out for liberty and right!

Well, my poor, dear wife, I, personally, feel sorry for you and the helpless little babes of our loins.

You I bequeath to the people, a woman of the people. I have one request to make of you: Commit no rash act to yourself when I am gone, but take up the great cause of Socialism where I am compelled to lay it down.

My children—well, their father had better die in the endeavor to secure their liberty and happiness than live contented in a society which condemns nine-tenths of its children to a life of wage-slavery and poverty. Bless them; I love them unspeakably, my poor helpless little ones.

Ah, wife, living or dead, we are as one. For you my affection is everlasting. For the people, humanity. I cry out again and again in the doomed victim’s cell: Liberty! Justice! Equality!

Albert R. Parsons.

Source: Lucy Parsons, Life of Albert R. Parsons (Chicago: 1889), 211–212.

See Also:

Haymarket Martyr Louis Lingg Says Good-bye"I Am Sorry Not to Be Hung": Oscar Neebe and the Haymarket Affair"We ask it; we demand it, and we intend to have it": Printer Albert R. Parsons Testifies before Congress about the Eight Hour Day“A Healthy Public Opinion”: Terence V. Powderly Distances the Knights of Labor from the Haymarket Martyrs

by Terence Powderly

The Haymarket Affair, as it is known today, began on May 1, 1886 when a labor protester threw a bomb at police, killing one officer, and ended with the arrest of eight anarchist leaders, three of whom were executed and none of whom was ever linked to the bombing. Some labor organizations saw the executed men as martyrs and tried to rally support but in the end, the hanging of the Haymarket anarchists not only emboldened capitalists, it undercut labor unity. Knights of Labor leader Terence V. Powderly was desperate to distance his organization from the accused anarchists and maintain the order’s respectability. In this excerpt from his 1890 autobiography Powderly explained his decision three years earlier to keep mainstream labor out of the furor that surrounded the Haymarket Affair.

I know that it may seem to be an arbitrary act on my part to rule a motion out of order, and did I not have excellent reasons for doing so I never would have availed myself of the privilege conferred upon me by virtue of the office I hold. To properly explain my reasons it will be necessary for me to take you back to the 1st of May, 1886, when the trade unions of the United States were in a struggle for the establishment of the eight-hour system. On that day was stricken to the dust every hope that existed for the success of the strike then in progress, and those who inflicted the blow claim to be representatives of labor. I deny their claim to that position, even though they may be workingmen. They represented no legitimate labor society, and obeyed the counsels of the worst foe this Order has upon the face of the earth to-day.

We claim to be striving for the elevation of the human race through peaceful methods, and yet are asked to sue for mercy for men who scorn us and our methods—men who were not on the street at the Chicago Haymarket in obedience to any law, rule, resolution or command of any part of this Order; men who did not in any way represent the sentiment of this Order in placing themselves in the attitude of opposing the officers of the law, and who sneer at our every effort to accomplish results. Had these men been there on that day in obedience to the laws of this society, and had they been involved in a difficulty through their obedience to our laws, I would feel it to be my duty to defend them to the best of my ability under the law of the land, but in this case they were there to counsel methods that we do not approve of; and no matter though they have lost no opportunity to identify this Order with anarchy, it stands as a truth that there does not exist the slightest resemblance between the two.

I warned those who proposed to introduce that resolution that I would rule it out of order, and that it would do harm to the condemned men to have it go out that this body had refused to pass such a resolution. I stated to them that I knew the sentiment of the men who came here, the sentiment of the order that sent them, and, knowing what that sentiment was, a resolution that in any way would identify this Order with anarchy could not properly represent that sentiment. You are not here in your individual capacity to act as individuals, and you cannot take upon yourselves to express your own opinion and then ask the Order at large to indorse it, for you are stepping aside from the path that your constituents instructed you to walk in.

This organization, among other things, is endeavoring to create a healthy public opinion on the subject of labor. Each member is pledged to do that very thing. How can you go back to your homes and say that you have elevated the Order in the eyes of the public by catering to an element that defies public opinion and attempts to dragoon us into doing the same thing? The eyes of the world are turned toward this convention. For evil or good will the vote you are to cast on this question affect the entire Order, and extreme caution must characterize your action. The Richmond session passed a vote in favor of clemency, but in such a way that the Order could not be identified with the society to which these men belong, and yet thousands have gone from the Order because of it. I tell you the day has come for us to stamp anarchy out of the Order, root and branch. It has no abiding place among us, and we may as well face the issue here and now as later on and at another place. Every device known to the devil and his imps has been resorted to to throttle this Order in the hope that on its ruins would rise the strength of anarchy.

During the year that has passed I have learned what it means to occupy a position which is in opposition to anarchy. Slander, vilification, calumny and malice of the vilest kind have been the weapons of the anarchists of America because I would not admit that Albert R. Parsons was a true and loyal member of the Knights of Labor. That he was a member is true, but we have had many members who were not in sympathy with the aims and objects of the order, and who would subordinate the Order to the rule of some other society. We have members, too, who could leave the Order for the Order’s good at any moment. Albert R. Parsons never yet counseled violence in obedience to the laws of Knighthood. I am told that it is my duty to defend the reputation of Mr. Parsons because he is a member of the Order. Why was not the obligation as binding on him? I have never lisped a word to his detriment either in public or private before. This is the first time that I have spoken about him in connection with the Haymarket riot, and yet the adherents of that damnable doctrine were not content to have it so; they accused me of attacking him, that I might, in denying it, say something in his favor. Why did Powderly not defend Parsons through the press since he is a Knight, and an innocent one? is asked. It is not my business to defend every member who does not know enough to take care of himself, and if Parsons is such a man he deserves no defense at my hands; but Parsons is not an ignorant man, and knows what he is doing. When men violate the laws and precepts of Knighthood, then no member is required to defend them. When Knights of Labor break the laws of the land in which they live, they must stand before the law the same as other men stand and be tried for their offenses, and not for being Knights.

This resolution does not come over the seal of either Local or District Assembly. It does not bear the seal of approval of any recognized body of the Order, and represents merely the sentiment of a member of this body, and should not be adopted in such a way as to give it the appearance of having the approval of those who are not here to defend themselves and the Order against that hell-infected association that stands as a foe of the most malignant stamp to the honest laborer of this land. I hate the name of anarchy. Through its encroachments it has tarnished the name of socialism and caused men to believe that socialism and anarchy are one. They are striving to do the same by the Knights of Labor. This they did intentionally and with malice aforethought in pushing their infernal propaganda to the front.

Pretending to be advanced thinkers, they drive men from the labor movement by their wild and foolish mouthings whenever they congregate, and they usually congregate where beer flows freely. They shout for the blood of the aristocracy, but will turn from blood to beer in a twinkling. I have no use for any of the brood, but am satisfied to leave them alone if they will attend to their own business and let this Order alone. They have aimed to capture this Order, and I can submit the proofs [here the documents were presented and read]. I have here also the expose of the various groups of anarchists of this country, and from them will read something of the aims of these mighty men of progress who would bring the greatest good to the greatest number by exterminating two-thirds of humanity to begin with. Possibly that is their method of conferring good.

No act of the anarchists ever laid a stone upon a stone in the building of this Order. Their every effort was against it, and those who have stood in the front, and have taken the sneers, insults and ridicule of press, pulpit and orator in defense of our principles, always have had the opposition of these devils to contend with also. I cannot talk coolly when I contemplate the damage they have done us, and then reflect that we are asked to identify ourselves with them even in this slight degree. Had the anarchists their way this body would not be in existence to-day to ask assistance from. How do you know that the condemned men want your sympathy? Have they asked you to go on your knees in supplication in seeking executive clemency for them? I think not, and, if they are made of the stuff that I think they are, they will fling back in your teeth the resolution you would pass. I give the men who are in the prison cell at Chicago credit for being sincere in believing that they did right. They feel that they have struggled for a principle, and feeling that way they should be, and no doubt are, willing to die for that principle.

Why, if I had done as they did, and stood in their place, I would die before I would sue for mercy. I would never cringe before a governor, or any other man, in a whine for clemency. I would take the consequences, let them be what they would. We may sympathize with them as much as we please, but our sympathies are due first to the Order that sent us here, and it were better that seven times seven men hang than to hang the millstone of odium around the standard of this Order in affiliating in any way with this element of destruction. If these men hang you may charge it to the actions of their friends [who have] strengthen[ed] the strands of the rope by their insane mouthings...

Be consistent and disband as soon as you pass this resolution, for you will have no further use of any kind for another General Assembly. You have imposed upon your General Master Workman the task of defending the Order from the attacks of its enemies, and he feels that he is entitled to at least a small share of the credit for giving the Order its present standing. He has to the best of his ability defended the Order, but its friends will place in the hands of its enemies the strongest weapon that was ever raised against it if they pass this resolution. Of what avail for me to go before the public and assert that we are a law-abiding set of men and women? What will it avail for me to strive to make public opinion for the Order when, with one short resolution, you sweep away every vestige of the good that has been done, for, mark it, the press stands ready to denounce us far and wide the moment we do this thing?

This resolution is artfully worded. Its sinister motive is to place us in the attitude of supporters of anarchy rather than sympathizers with men in distress, and it should be defeated by a tremendous majority. It is asserted that this does not amount to anything, and that it is not the intention to identify the Order at large with these men. No more barefaced lie was ever told. That resolution would never be offered if we did not represent so large a constituency, and if it passes twenty-four hours won’t roll over your heads until you see anarchists all over the land shouting that if these men are hanged the Knights of Labor will take revenge at the polls and elsewhere. In passing that resolution you place the collar of anarchy around your necks, and no future act of ours can take It off. If you sympathize with these unfortunate men, why do you lack the manhood to sign a petition for the commutation of their sentence, as individuals, and stand upon your own manhood, instead of sneaking behind the reputation and character of this great Order, which owes everything it has gained to having nothing to do with the anarchists? Pass this vote if you will, but I swear that I will not be bound by any resolution that is contrary to the best interests of the Order. You cannot pass a resolution to muzzle me, and I will not remain silent after the adjournment of this convention if it becomes necessary to defend the Order from unjust assaults as a result of the action taken.

As an Order we are striving for the establishment of justice for industry. We are attempting to remove unjust laws from the statutes, and are doing what we can to better the condition of humanity. At every step we have to fight the opposition of capital, which of itself is sufficient to tax our energies to the utmost; but at every step we are handicapped by the unwarrantable and impertinent interference of these blatant, shallow-pated men, who affect to believe that they know all that is worth knowing about the conditions of labor, and who arrogate to themselves the right to speak for labor at all times and under all circumstances. That they are mouth-pieces is true, but they only speak for themselves, and do that in such a way as to alarm the community and arouse it to such a pitch of excitement that it insists upon the passage of restrictive legislation, which, unfortunately, does not reach the men whose rash language calls for its passage. Its effects are visited upon innocent ones who had no hand, act or part in formenting the discord which preceded the passage of the unjust laws.

Our greatest trouble has always been caused by extremists who, without shadow of authority, attempted to voice the sentiments of this Order; and from this day forward I am determined that no sniveling anarchist will speak for me, and if he attempts it under shadow of this organization, then he or I must leave the Order, for I will not attempt to guide the affairs of a society that is so lacking in manhood as to allow the very worst element of the community to make use of the prestige it has gained to promote the vilest of schemes against society. I have never known a day when these creatures were not ready to stab us to the heart when our faces were turned toward the enemy of labor.

It is high time for us to assert our manhood before these men throttle it, For Parsons and the other condemned men let there be mercy. I have no grudge against them. In fact, I would never trouble my head about them were it not for the welfare of this Order. Let us as individuals express our sorrow for their unhappy plight, if we will; but as an Order we have no right to do so. It is not the individuals who are in prison at Chicago that I speak against. It is the hellish doctrine which found vent on the streets of Chicago, and which, unfortunately for themselves, they have been identified with. No, I do not hate these men, I pity them; but for anarchy I have nothing but hatred, and if I could I would forever wipe from the face of the earth the last vestige of its doubledamned presence, and in doing so would feel that the best act of my life, in the interest of labor, had been performed.

Source: Terence V. Powderly, Thirty Years of Labor, 1859–1889 (Philadelphia: T.V. Powderly, 1890).

See Also:

"His Act is Doublely Despicable": Albert Parsons Responds to His Condemnation by Terence V. PowderlyFind blog posts, photos, events and more off-site about: