I originally posted here about Lucy Parsons for Black History Month. Here are some updates from the web about Lucy. And as you read about her you realize that she could be celebrated during Womens History Month, Labour History Month, as Mexican American an Indigenous woman, an American proletarian revolutionary.

As I researched this post I came across a number of references to Lucy being a member or supporter of the Communist Party of the USA.

This is a historiographical case of mistaken identity confusing her with her wobbly sister Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, the Rebel Girl, who was national Chairman of the CPUSA.

Lucy was a Revolutionary Socialist and Anarchist till the end of her life.

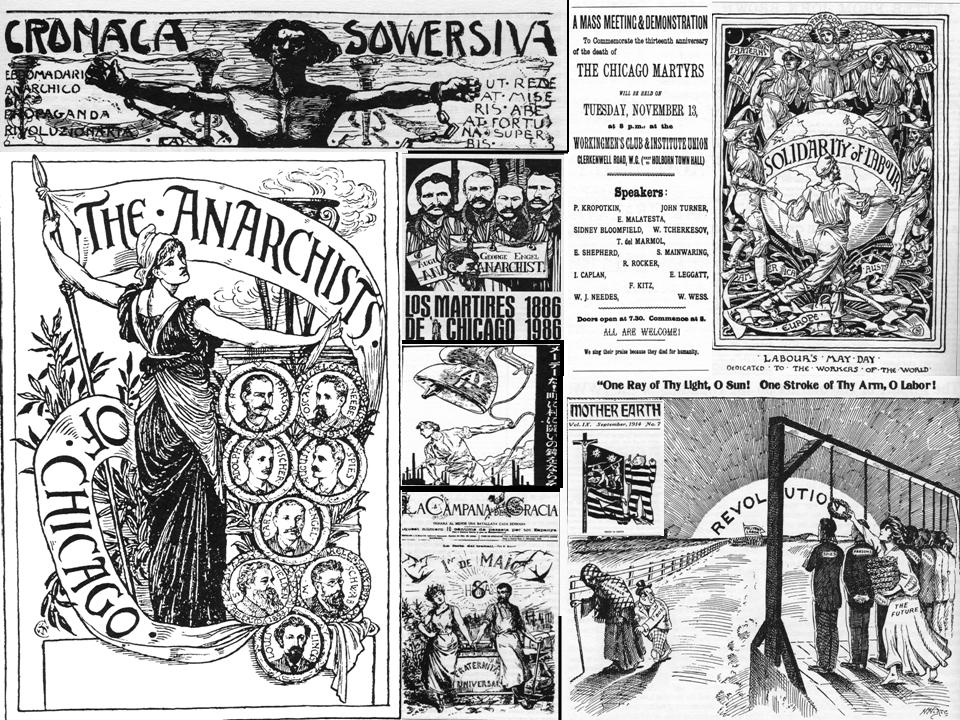

A Fury For Justice: Lucy Parsons And The Revolutionary Anarchist Movement in Chicago

For six and a half decades Lucy Parsons played a pivotal role in some

of the most influential social movements of her time. A fiery speaker,

bold social critic, and tireless organizer, Parsons was a prominent figure

in radical American political movements from the late 1870s until

her death at the age of 89 on March 7th, 1942. Despite playing an

important part in such iconic struggles as the movement for the 8-

hour day, the defense of the Haymarket martyrs, and the founding

of the IWW, Lucy Parsons has been largely ignored by historians of

all stripes. Parsons sole biographer, writing in 1976, explained her

invisibility thusly: “Lucy Parsons was black, a woman, and working

class — three reasons people are often excluded from history.”1

While this helps explain in part Parsons’ absence from mainstream

historiography, it is not entirely satisfying. While other working

class black women found their way into academic writing and political

iconography with the rise of Black Nationalist movements in

the 1960s and 70s and the concurrent proliferation of Black Studies

programs at American universities, Lucy Parsons was mostly left behind.

Unfortunately, when she has been included in academic writing

she has usually not been allowed to speak for herself. Most of the

academics that have mentioned Lucy Parsons (generally very briefly)

have recast her as they would have preferred her to be, usually as

either a reflection of their own politics or as an example of the failures

of past movements. The only biography of Parsons, Carolyn

Ashbaugh’s Lucy Parsons: American Revolutionary, combines misrepresentation

with inaccuracy. Ashbaugh nonsensically claims that

Parsons was not an anarchist, a fact beyond the point of argument

for anyone that has read Lucy Parsons’s work, and she groundlessly

claims that Parsons joined the Communist Party towards the end of

her life. Sadly, this has allowed every writer after Ashabugh to make

the same erroneous claim

FOUNDING CONVENTION

Industrial Workers of the World

THIRD DAY

Thursday, June 29, 1905

AFTERNOON SESSION

SPEECH OF LUCY E. PARSONS

DEL. LUCY E. PARSONS: I can assure you that after the intellectual feast that I have enjoyed immensely this afternoon, I feel fortunate to appear before you now in response to your call. I do not wish you to think that I am here to play upon words when I tell you that I stand before you and feel much like a pigmy before intellectual giants, but that is only the fact. I wish to state to you that I have taken the floor because no other woman has responded, and I feel that it would not be out of place for me to say in my poor way a few words about this movement.

We, the women of this country, have no ballot even if we wished to use it, and the only way that we can be represented is to take a man to represent us. You men have made such a mess of it in representing us that we have not much confidence in asking you; and I for one feel very backward in asking the men to represent me. We have no ballot, but we have our labor. I think it is August Bebel, in his “Woman in the Past, Present and Future”—a book that should be read by every woman that works for wages—I think it is Bebel that says that men have been slaves through-out all the ages, but that woman’s condition has been worse, for she has been the slave of a slave. I think there was never a greater truth uttered. We are the slaves of the slaves. We are exploited more ruthlessly than men. Wherever wages are to be reduced the capitalist class use women to reduce them, and if there is anything that you men should do in the future it is to organize the women.

And I tell you that if the women had inaugurated a boycott of the State street stores since the teamsters’ strike they would have surrendered long ago. (Applause). I do not strike before you to brag. I had no man connected with that strike to make it of interest to me to boycott the stores, but I have not bought one penny’s worth there since that strike was inaugurated. I intended to boycott all of them as one individual at least, so it is important to educate the women. Now I wish to show my sisters here that we fasten the chains of slavery upon our sisters, sometimes unwittingly, when we go down to the department store and look around for cheap bargains and go home and exhibit what we have got so cheap. When we come to reflect it simply means the robbery of our sisters, for we know that the things cannot be made for such prices and give the women who made them fair wages.

I wish to say that I have attended many conventions in the twenty-seven years since I came here to Chicago’ a young girl, so full of life and animation and hope. It is to youth that hope comes; it is to age that reflection comes. I have attended conventions from that day to this of one kind and another and taken part in them. I have taken part in some in which our Comrade Debs had a part. I was at the organization that he organized in this city some eight or ten years ago. Now, the point I want to make is that these conventions are full of enthusiasm. And that is right; we should sometimes mix sentiment with soberness; it is a part of life. But, as I know from experience, there are sober moments ahead of us, and when you go out of this hall, when you have laid aside your enthusiasm, then comes solid work. Are you going out with the reflection that you appreciate and grasp the situation that you are to tackle? Are you going out of here with your minds made up that the class in which we call ourselves, revolutionary Socialists so-called—that that class is organized to meet organized capital with the millions at its command? It has many weapons to fight .us. First it has money. Then it has legislative tools. Then it has its judiciary; it has its army and its navy; it has its guns; it has armories; and last, it has the gallows. We call ourselves revolutionists. Do you know what the capitalists mean to do to you revolutionists? I simply throw these hints out that you young people may become reflective and know what you have to face at the first’ and then it will give you strength. I am not here to cause any discouragement, but simply to encourage you to go on in your grand work.

Now, that is the solid foundation that I hope this organization will be built on; that it may be built not like a house upon the sand, that when the waves of adversity come it may go over into the ocean of oblivion; but that it shall be built upon a strong, granite, hard foundation; a foundation made up of the hearts, and aspirations of the men and women of this twentieth century who have set their minds, their bands, their hearts and their heads against the past with all its miserable poverty, with its wage slavery, with its children ground into dividends, with its miners away down under the earth and with never the light of sunshine, and with its women selling the holy name of womanhood for a day’s board. I hope we understand that this organization has set its face against that iniquity, and that it has set its eyes to the rising star of liberty, that means fraternity, solidarity, the universal brotherhood of man. I hope that while politics have been mentioned here I am not one of those who, because a man or woman disagrees with me, cannot act with them—I am glad and proud to say I am too broad-minded to say they are a fakir or fool or a fraud because they disagree with me. My view may be narrow and theirs may be broad; but I do say to those who have intimated politics here as being necessary or a part of this organization, that I do not impute to them dishonesty or impure motives. But as I understand the call for this convention, politics had no place here; it was simply to be an economic organization, and I hope for the good of this organization that when we go away from this hall, and our comrades go some to the west, some to the east, some to the north and some to the south, while some remain in Chicago, and all spread this light over this broad land and carry the message of what this convention has done, that there will be no room for politics at all. There may be room for politics; I have nothing to say about that; but it is a bread and butter question, an economic issue, upon which the fight must be made.

Now, what do we mean when we say revolutionary Socialist? We mean that the land shall belong to the landless, the tools to the toiler, and the products to the producers. (Applause.) Now, let us analyze that for just a moment, before you applaud me. First, the land belongs to the landless. Is there a single land owner in this country who owns his land by the constitutional rights given by the constitution of the United States who will allow you to vote it away from him? I am not such a fool as to believe it. We say, “The tools belong to the toiler.” They are owned by the capitalist class. Do you believe they will allow you to go into the halls of the legislature and simply say, “Be it enacted that on and after a certain day the capitalist shall no longer own the tools and the factories and the places of industry, the ships that plow the ocean and our lakes?” Do you believe that they will submit? I do not. We say, “The products belong to the producers.” It belongs to the capitalist class as their legal property. Do you think that they will allow you to vote them away from them by passing a law and saying, “Be it enacted that on and after a certain day Mr. Capitalist shall be dispossessed?” You may, but I do not believe it. Hence, when you roll under your tongue the expression that you are revolutionists, remember what that word means. It means a revolution that shall turn all these things over where they belong to the wealth producers. Now, how shall the wealth producers come into possession of them? I believe that if every man and every woman who works, or who toils in the mines, the mills, the workshops, the fields, the factories and the farms in our broad America should decide in their minds that they shall have that which of right belongs to them, and that no idler shall live upon their toil, and when your new organization, your economic organization, shall declare as man to man and women to woman, as brothers and sisters, that you are determined that you will possess these things, then there is no army that is large enough to overcome you, for you yourselves constitute the army. (Applause). Now, when you have decided that you will take possession of these things, there will not need to be one gun fired or one scaffold erected. You will simply come into your own, by your own independence and your own manhood, and by asserting your own individuality, and not sending any man to any legislature in any State of the American Union to enact a law that you shall have what is your own; yours by nature and by your manhood and by your very presence upon this earth.

Nature has been lavish to her children. She has placed in this earth all the material of wealth that is necessary to make men and women happy. She has given us brains to go into her store house and bring from its recesses all that is necessary. She has given us these two hands and these brains to manufacture them suited to the wants of men and women. Our civilization stands on a parallel with all other civilizations. There is just one thing we lack, and we have only ourselves to blame if we do not become free. We simply lack the intelligence to take possession of that which we have produced. (Applause). And I believe and I hope and I feel that the men and women who constitute a convention like this can come together and organize that intelligence. I must say that I do not know whether I am saying anything that interests you or not, but I feel so delighted that I am talking to your heads and not to your hands and feet this afternoon. I feel that you will at least listen to me, and maybe you will disagree with me, but I care not; I simply want to shed the light as I see it. I wish to say that my conception of the future method of taking possession of this is that of the general strike: that is my conception of it. The trouble with all the strikes in the past has been this: the workingmen like the teamsters in our cities, these hard-working teamsters, strike and go out and starve. Their children starve. Their wives get discouraged. Some feel that they have to go out and beg for relief, and to get a little coal to keep the children warm, or a little bread to keep the wife from starving, or a little something to keep the spark of life in them so that they can remain wage slaves. That is the way with the strikes in the past. My conception of the strike of the future is not to strike and go out and starve, but to strike and remain in and take possession of the necessary property of production. If any one is to starve—I do not say it is necessary—let it be the capitalist class. They have starved us long enough, while they have had wealth and luxury and all that is necessary. You men and women should be imbued with the spirit that is now displayed in far-off Russia and far-off Siberia where we thought the spark of manhood and womanhood had been crushed out of them. Let us take example from them. We see the capitalist class fortifying themselves to-day behind their Citizens’ Associations and Employers’ Associations in order that they may crush the American labor movement. Let us cast our eyes over to far-off Russia and take heart and courage from those who are fighting the battle there, and from the further fact shown in the dispatches that appear this morning in the news that carries the greatest terror to the capitalist class throughout all the world—the emblem that has been the terror of all tyrants through all the ages, and there you will see that the red flag has been raised. (Applause). According to the Tribune, the greatest terror is evinced in Odessa and all through Russia because the red flag has been raised. They know that where the red flag has been raised whoever enroll themselves beneath that flag recognize the universal brotherhood of man; they recognize that the red current that flows through the veins of all humanity is identical, that the ideas of all humanity are identical; that those who raise the red flag, it matters not where, whether on the sunny plains of China, or on the sun-beaten hills of Africa, or on the far-off snow-capped shores of the north, or in Russia or in America—that they all belong to the human family and have an identity of interest. (Applause). That is what they know.

So when we come to decide, let us sink such differences as nationality, religion, politics, and set our eyes eternally and forever towards the rising star of the industrial republic of labor; remembering that we have left the old behind and have set our faces toward the future. There is no power on earth that can stop men and women who are determined to be free at all hazards. There is no power on earth so great as the power of intellect. It moves the world and it moves the earth.

Now, in conclusion, I wish to say to you—and you will excuse me because of what I am going to say and only attribute it to my interest in humanity. I wish to say that nineteen years ago on the fourth of May of this year, I was one of those at a meeting at the Haymarket in this city to protest against eleven workingmen being shot to pieces at a factory in the southeastern part of this city because they had dared to strike for the eight-hour movement that was to be inaugurated in America in 1886. The Haymarket meeting was called primarily and entirely to protest against the murder of comrades at the McCormick factory. When that meeting was nearing its close some one threw a bomb. No one knows to this day who threw it except the man who threw it. Possibly he has rendered his account with nature and has passed away. But no human being alive knows who threw it. And yet in the soil of Illinois, the soil that gave a Lincoln to America, the soil in which the great, magnificent Lincoln was buried in the State that was supposed to be the most liberal in the union, five men sleep the last sleep in Waldheim under a monument that, has been raised there because they dared to raise their voices for humanity. I say to any of you who are here and who can do so, it is well worth your time to go out there and draw some inspiration around the graves of the first martyrs who fell in the great industrial struggle for liberty on American soil. (Applause). I say to you that even within the sound of my voice, only two short blocks from where we meet to-day, the scaffold was erected on which those five men paid the penalty for daring to raise their voices against the iniquities of the age in which we live. We arc assembled here for the same purpose. And do any of you older men remember the telegrams that were sent out from Chicago while our comrades were not yet even cut down from the cruel gallows? “Anarchy is dead, and these miscreants have been put out of the way.” Oh, friends, I am sorry that I even had to use that word, “anarchy” just now in your presence, which was not in my mind at the outset. So if any of you wish to go out there and look at this monument that has been raised by those who believed in their comrades’ innocence and sincerity, I will ask you, when you have gone out and looked at the monument, that you will go to the reverse side of the monument and there read on the reverse side the words of a man, himself the purest and the noblest man who ever sat in the gubernatorial chair of the State of Illinois, John P. Altgeld. (Applause). On that monument you will read the clause of his message in which he pardoned the men who were lingering then in Joliet. I have nothing more to say. I ask you to read the words of Altgeld, who was at that time the governor, and had been a lawyer and a judge, and knew whereof he spoke, and then take out your copy books and copy the words of Altgeld when he released those who had not been slaughtered at the capitalists’ behest, and then take them home and change your minds about what those men were put to death for.

Now, I have taken up your time in this because I simply feel that I have a right as a mother and as a wife of one of those sacrificed men to say whatever I can to bring the light to bear upon this conspiracy and to show you the way it was. Now, I thank you for the time that I have taken up of yours. I hope that we will meet again some time, you and I, in some hall where we can meet and organize the wage workers of America, the men and women, so that the children may not go into the factories, nor the women into the factories, unless they go under proper conditions. I hope even now to live to see the day when the first dawn of the new era of labor will have arisen, when capitalism will be a thing of the past, and the new industrial republic, the commonwealth of labor, shall be in operation. I thank you. (Applause.)

The utopian colony of Home was founded in 1896 on Von Geldern Cove, across the Tacoma Narrows on the Key Peninsula. Established by three families who were refugees from another failed utopian community, it became in time a successful anarchist colony whose most famed inhabitant was the sometimes elusive Jay Fox, anarchist and labor radical.

In 1904 Fox worked closely with Lucy Parsons, widow of the Haymarket martyr Albert Parsons, in an attempt to launch an anarchist, English-language newspaper. In the spring of that year Parsons, Fox and others discussed the possibility of starting a paper to replace The Free Society which had folded in the wake of the persecution of radicals following the McKinley assassination. Throughout the summer the group held socials and picnics to raise money for the cause.

However, by late summer a rift had developed between Fox and Parsons. A group headed by Fox felt that The Demonstrator of Home Colony should be adopted and backed. The other faction, headed by Parsons, felt strongly that such a paper should emanate from the radical and industrial center of Chicago rather than from the backwater colony of Home. Before the controversy was settled, Fox sent the money to Home. Parsons, undaunted, started a Chicago-based paper, The Liberator. It should be noted that Fox had good reason for his position. He had been invited to assume the editorship of The Demonstrator, planning to move to Home in the fall of 1905. He was delayed that fall and again in the spring.

by Robert Black

Not for its intrinsic interest - no part of this book has much of that - but as a case study in Salerno's shortcomings, let me review in much more detail than it deserves his chapter on "Anarchists at the Founding Convention." Here is his most of his case for significantly raising prevailing estimates of anarchist influence on the IWW. He first cites the expressions of solidarity with the Haymarket anarchists martyred two decades before which issued from the podium; there was even a pilgrimage to their graves. Indeed , one of the opening speakers was Lucy Parsons, widow of executed Haymarket defendant Albert Parsons.(112) Mrs. Parsons, however, was so far from speaking as an anarchist that she actually apologized for using the word "anarchy." As Joseph Conlin described the scene, "while almost all the delegates claimed to be socialists, there was also present a small group of anarchists, the remnants of the Chicago group. Lucy Parsons was honored by a prominent seat and spoke several times. But she functioned primarily as platform decoration and had little influence on the proceedings. Her ignominious role characterized the dilemma of the less eminent anarchists: tolerated in attendance, they went all but unheard. Mrs. Parsons sheepishly apologized for employing the term 'anarchy' in a speech, and the few avowedly anarchist proposals that reached the floor were summarily rejected."(113)

None of this is evidence of anarchist influence at the founding convention. The Haymarket labor martyrs had been anarchists - although even that has been called into question(114) -- but they were commemorated in Chicago, not as anarchists, but as labor martyrs. By then, their anarchism long since interred with them, they were remembered as heroic leaders of the eight-hour movement, a lowest common denominator cause any unionist could rally around at a convention bent on forging unity. (115) That they assembled in Chicago made it only that much more obligatory as a matter of common courtesy to pay homage to the local heroes. The presence of Lucy Parsons on the platform had exactly, and only, the honorific significance of the presence of, say, Coretta King on the platform of a Democratic Party convention. Coretta King has no influence on the Democrats and Lucy Parsons had none on the Wobblies.

Women that Wobbled but Didn’t Fall Down

Lucy Parsons, an adamant socialist and ‘Wobbly’ (a term for IWW members), stands out as a great example of a woman in the IWW. While little is known about her earliest background, we do know that she was born in 1853. Her ethnicity was the convergence of African, Mexican and Native roots, and, because of this, she was keenly aware of injustices in society in respect to those groups to which she belonged (Bird, Georgakas and Schaffer). Furthermore, it is supposed that she was born into slavery, which, again, gives her an interesting perspective in regards to the injustices perpetrated by the rich on the destitute.Lucy Parsons was born in Texas in 1853 (most likely as a slave) to parents of Native, African and Mexican American ancestry. She was an anarchist labor activist and powerful orator who fought against poverty, capitalism, social injustice and racism her whole life.

She married Albert Parsons, a former confederate soldier, in 1871. During that time, the South was instituting repressive Jim Crow laws and Lucy and Albert fled north to Chicago . The Chicago Police Department described her as “more dangerous than a thousand rioters” in the 1920s. Lucy and Albert were highly effective anarchist organizers involved in the labor movement in the late 19 th Century. They also participated in revolutionary activism on behalf of political prisoners, people of color, the homeless and women. Albert was fired from his job at the Times because of his involvement in organizing workers and blacklisted in the Chicago printing trade. Lucy opened a dress shop to support her family and hosted meetings for the International Ladies' Garment Workers Union (ILGWU). She began to write for the radical papers The Socialist and The Alarm , weekly publications of the International Working People's Association (IWPA) which she and Albert were among the founders of in 1883.

By 1886, tension among workers across America was high due to horrid working conditions and the squelching of union activities by authorities. A peaceful strike at McCormick Harvest Works in Chicago became violent when police fired into the crowd of unarmed strikers. Many were wounded and four were killed. Radicals called a meeting in Haymarket Square and once again, this peaceful gathering turned violent when someone threw a bomb that killed a police officer. Although Albert was not present at Haymarket, he was arrested and executed on charges that he had conspired in the Riot.

In the years following the execution, Lucy lived in poverty but remained committed to the cause. In 1892, she began editing Freedom: A Revolutionary Anarchist-Communist Monthly and was frequently arrested for public speaking and distributing anarchist literature. Then, in 1905, she helped found the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and began editing The Liberator , a paper published by the IWW and based in Chicago . Here she was able to voice her opinions on women's issues, supporting a woman's right to divorce, remarry and have access to birth control. She organized the Chicago Hunger Demonstrations in 1915, which pushed the American Federation of Labor, the Socialist Party and Jane Addam's Hull House to participate in a huge demonstration on February 12.

In 1925, she began working with the National Committee of the International Labor Defense, a Communist Party group that aided with the Scottsboro Eight and Angelo Hearndon cases. These were cases where the establishment charged African-American organizers with crimes they did not commit.

With eyesight failing, she spoke at the International Harvester in February, 1941. She fought against oppression until her death in 1942 at the age of 89 when she died in an accidental house fire. Her boyfriend died the next day from injuries he sustained while trying to save her. Adding to this tragedy, the FBI stole her library of 1,500 books and all of her personal papers. The state still viewed Lucy Parsons as a threat, even in her death.

WILLIAMS, Casey. "Whose Lucy Parsons ? The mythologizing and re-appropriation of a radical hero".

Anarcho-Syndicalist Review number 47, Summer, 2007

As a radical anarchist, Lucy Parsons dedicated over sixty years of her life to fighting for America’s working class and poor. [1] and A skillful orator and passionate writer, Parsons played an important role in the history of American radicalism, especially in the labor movement of the 1880s, and remained an active force until her death in 1942. The one question from which she never swayed was "how to lift humanity from poverty and despair ?" [2] With this question propelling her life’s work, Parsons was active in a multitude of radical organizations including the Socialistic Labor Party, the International Working People’s Association, and the Industrial Workers of the World. Coupled with her long involvement in America’s labor movement was Parsons’ unbending anarchist vision of society, a philosophy which underlay her critique of America’s oppressive economic and political institutions.

Peter Linebaugh: Joe Hill and the IWW

Rosemont has a crucial chapter on the indigenous people. Lucy Parsons, "whose high cheek bones of her Indian ancestors" as her biographer says, provided the physiognomy of a countenance of utter inspiration when she spoke at the founding convention of the IWW August Spies lived with the Ojibways; Big Bill Haywood attended pow-wows. Abner Woodruff, a Wob, had a chapter on Indian agriculture in his Evolution of American Agriculture (1915-6). The Wobblies were "the spiritual successors to the Red Indians as number one public enemy and conscience botherers." Frank Little, the most effective Wobbly organizer, was lynched in Butte, Montana, by the same hard rock copper "bosses" which caused Joe Hill to be shot. Little was a Cherokee Indian.The Wheatland Riot, The Bisbee Deportation, IWW Ties with Mexico, Workers of the World

Thus Lucy Parsons, already renowned for her defense of her husband after the Haymarket incident in 1886 and as an African-American revolutionary in Chicago, famously spoke for the most lowly, women driven to prostitution. But she also spoke of workers' capacity, arguing: "My conception of the strike of the future is not to strike and go out and starve, but to strike and remain in and take possession of the necessary property of production." In this way, the extraordinary veteran of nineteenth-century class, race, and gender struggles predicted the sit-down strike of the future, which took place first in factories, then at sit-ins to integrate public facilities, and still later in college classrooms and presidents' offices to protest the brutal war on Vietnam.Class Struggles and Geography:

Revisiting the 1886 Haymarket Square Police Riot

Regardless of how one interprets Haymarket, their memory would have

vanished altogether by the next generation without recent efforts and those of Lucy

Parsons, along with other anarchists and labour activists, to recount and publish

Haymarket accounts. In this manner, Haymarket became an integral part of labour

movements’ lore, especially in Latin America and southern and eastern Europe.

Between 1887 and today, with uneven speed and through differing circumstances

and motivations, Haymarket was turned into the basis of a holiday with the

establishment of the first of May as labour-day in most of the world. Even if that

history was appropriated by state socialist dictatorships for their own

propagandistic and geopolitical ends during the middle and late twentieth centuries,

it remained a symbol of workers’ struggle for rights and dignity in the workplace, if

not a struggle for socialism. In the US, however, the holiday, along with its radical

referent, was banned by 1955. The observance was not revived until the 1970s with

the endeavours of veteran union activists and the renewed spread and

popularisation of anarchist perspectives (Avrich, 1984, 428-436; Green, 2006, 301-

320; Zinn, 1995, 267).

LUCY PARSONS

Lucy also wrote about the press, and how even in her own time, newspapers suppressed and manipulated information with their disinformation and misinformation in reporting incidents which occurred. Lucy wrote essays, “The Importance of a Press” and “Challenging the Lying Monopolistic Press” that alerted people that the fourth estate could be just as destructive to citizen’s interests as much as any robber baron, or government institution.

Her writings on sex and patriarchy, as well as her thoughts on race and racism, require closer reading, and certainly deserve greater attention.

In February, 1941, in one of her last major appearances, Lucy spoke at the International Harvestor, where she continued to inspire crowds. On March 7, 1942 at the age of 90, Lucy died from a fire that engulfed her home.

Her lover George Markstall died the next day from wounds he received while trying to save her. To add to this tragedy, when Lucy Parsons died, the police seized and destroyed her letters, writings and library. She almost disappeared from history, but, many of her writings did survive.

Lucy’s library of 1,500 books on sex, socialism and anarchy were mysteriously stolen, along with all of her personal papers. Neither the FBI nor the Chicago police told Irving Abrams, who had come to rescue the library, that the FBI had already confiscated all of her books. The struggle for fundamental freedom of speech, in which Lucy had engaged throughout her life, continued through her death as authorities still tried to silence this radical woman by robbing her of the work of her lifetime.

She is buried near her husband, near the Haymarket Monument.

Lucy Parsons and the call for class war -notmytribe.com

Lucy lived well up into this century,well into this century, died in 1940.

One time, she was speaking at a big May Day rally

back in the Haymarket in the middle 1930s, she was incredibly old.

She was led carefully up to the rostrum, a multitude of people there.

She had her hair tied back in a tight white bun, her face

a mass of deeply incised lines, deep-set beady black eyes.

She was the image of everybody’s great-grandmother.

She hunched over that podium, hawk-like,

and fixed that multitude with those beady black eyes,

and said: “What I want

is for every greasy grimy tramp

to arm himself with a knife or a gun

and stationing himself at the doorways of the rich

shoot or stab them as they come out.”

Looking for Lucy (in all the wrong places)

Considering Lucy Parsons’s life as a muckraker, incendiary wordsmith, and all-around thorn in the side of the established order, the Chicago Park District should have expected the flurry of controversy it got when it decided to name a park for her. Like most controversies, this one has made some fairly preposterous bedfellows. The two groups most vociferously opposed to naming a city park after Parsons have been the Fraternal Order of Police, and local anarchists who insist that any government-sanctioned recognition dishonors Parsons’s anarchist legacy.In tracking this little gush of new blood from an old wound, I’ve gained an even deeper understanding of just how tortured Chicago’s relationship with its radical history is. Lucy Parsons — the anarchist formerly known to the American labor movement as one of its founding mothers, and to the Chicago Police Department as “more dangerous than a thousand rioters” — is barely known to most Chicagoans today, including the city officials who supported the park-naming. In what is surely one of the greatest ironies in the history of Chicago’s civic life, the cops were the only ones who went on record openly acknowledging Parsons’s anarchism, while her supporters both in and out of local government labored to recast her merely as a champion of rights for women and minorities (which she was, but only by extension of her lifelong fight for workers’ revolution).

Lucy Parsons :: Revolutionary Feminist

Class, Race and Gender

Parsons’ commitments towards freedom of the young Black Communist Angelo Herndon in Georgia, Tom Mooney in California, and for the Scottsoboro Nine in Alabama were unflinching. Parsons recognized the class system in America as the prime factor in perpetuating racism. She was the foremost American feminist to declare that race, gender and sexuality are not oppressed identities by themselves. It is the economic class that determines the level of oppression people of minorities have to confront. Notwithstanding her social location of being a black and a woman, Parsons declared that a black person in America is exploited not because she/he is black. “It is because he is poor. It is because he is dependent. Because he is poorer as a class than his white wage-slave brother of the North.”

Lucy Parsons was a relentless defender of working class rights. To contain her popularity, the media portrayed her more as the wife of Albert Parsons – a Haymarket martyr, who was murdered by the state of Illinois, while demanding for eight-hour working day on November 11, 1887. While identifying her with Albert’s causes, history textbooks – both liberal and conservative – seldom mention Parsons as the radical torchbearer of American communist movement.

Parsons was among the first women to join the founding convention of IWW. She thundered: “We, the women of this country, have no ballot even if we wished to use it. But we have our labor. Wherever wages are to be reduced, the capitalist class uses women to reduce them.”

In The Agitator, dated November 1, 1912 she referred to Haymarket martyrs thus: “Our comrades were not murdered by the state because they had any connection with the bombthrowing, but because they were active in organizing the wage-slaves. The capitalist class didn’t want to find the bombthrower; this class foolishly believed that by putting to death the active spirits of the labor movement of the time, it could frighten the working class back to slavery.”

She had no illusions about capitalistic world order. Parsons called for armed overthrow of the American ruling class. She refused to buy into an argument that the origin of racist violence was in racism. Instead, Parsons viewed racism as a necessary byproduct of capitalism. In 1886, she called for armed resistance to the working class: “You are not absolutely defenseless. For the torch of the incendiary, which has been known with impunity, cannot be wrested from you!”

For Parsons, her personal losses meant nothing; her oppression as a woman meant less. She was dedicated to usher in changes for the entire humanity – changes that would alter the world order in favor of the working poor class.

Even as a founding member of IWW, she was not willing to let the world’s largest labor union function in a romanticized manner. She radicalized the IWW by demanding that women, Mexican migrant workers and even the unemployed become full and equal members.

With her clarity of vision, lifelong devotion towards communist causes, her strict adherence to radical demands for a societal replacement of class structure, Lucy Parsons remains the most shining example of an American woman who turned her disadvantaged social locations of race and gender, to one of formidable strength – raising herself to bring about emancipated working class consciousness.

Baron, Fanya nee Anisimovna aka Fanny Baron 188?-1921 | libcom.org

Idealistic young anarchist who suffered the brutality of both the US cops and the Russian Cheka.

Born in Russia, Fanya Anisimovna moved to the United States where she established a relationship with Aron Baron (aka Kantarovitch), who worked as a baker. She was active in the anarchist movement in Chicago, and with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). She was involved in the hunger demonstrations of 1915 there, alongside Lucy Parsons and Aron. On January 17th 1915 she led the Russian Revolutionary Chorus at a meeting addressed by Lucy Parsons and others at Hull House, established by Jane Addams to help the poor. On the demonstration outside the police viciously attacked. Plain clothes detectives used brass knuckles on the crowd, while uniformed cops struck out with billy clubs. Fanya was knocked unconscious by one of the club wielding cops. She and five other Russian women and fifteen men were arrested. Jane Addams arranged bail for Fanya, Lucy and others who were pictured in the Chicago press.FREEDOM, EQUALITY & SOLIDARITY

Writings & Speeches 1878-1937

Edited & Introduced by Gale Ahrens

With an Afterword by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

"The most prominent black woman radical of the late nineteenth century, Lucy Parsons [was also] one of the brightest lights in the history of revolutionary socialism."-Robin D. G. Kelley, in Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination.

"Lucy Parsons's writings are among the best and strongest in the history of U.S. anarchism. Although written long ago, these texts tackle the major problems of our time. Her long and often traumatic experience of the capitalist injustice system-from KKK terror in her youth, through Haymarket and the judicial murder of her husband, to the U.S. government's war on the Wobblies -made her not "just another victim" but an extraordinarily articulate witness to, and vehement crusader against, all injustice. That kind of direct experience gave her a credibility and an actuality that those who lack such experience just don't have. Lucy Parsons's life and writings reflect her true-to-the-bone heroism. Her language sparkles with the love of freedom and the passion of revolt."

- Gale Ahrens, Introduction

"More dangerous than 1000 rioters!" That's what the Chicago police called Lucy Parsons- America's most defiant and persistent anarchist agitator, whose cross-country speaking tours inspired hundreds of thousands of working people. Her friends and admirers included William Morris, Peter Kropot-kin, "Big Bill" Haywood, Ben Reitman, Sam Dolgoff-and the groups in which she was active were just as varied: the Knights of Labor, IWW, Dil Pickle Club, International Labor Defense, & others. Here for the first time is a hefty selection of her powerful writings & speeches-on anarchism, women, race matters, class war, the IWW, and the U.S. injustice system.

"Lucy Parsons's personae and historical role provide material for the makings of a truly exemplary figure ... Think of it: a lifelong anarchist, labor organizer, writer, editor, publisher, and dynamic speaker, a woman of color of mixed black, Mexican, and Native American heritage, founder of the 1880s Chicago Working Woman's Union that organized garment workers, called for equal pay for equal work, and even invited housewives to join with the demand of wages for housework; and later (1905) co-founder the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), which made the organizing of women and people of color a priority. . .For a better understanding of the concept of direct action and its implications, no other historical figure can match the lessons provided by Lucy Parsons."- Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz, Afterword

Hobohemia: Emma Goldman, Lucy Parsons, Ben Reitman & Other ...

www.alibris.com/booksearch?qwork=10370395&matches... - Cached