Post on: August 2, 2020

Doug Enaa Greene

Harrison Fluss

Marxism is the completion of the Radical Enlightenment project.

Part I | II | III | IV | V | VI

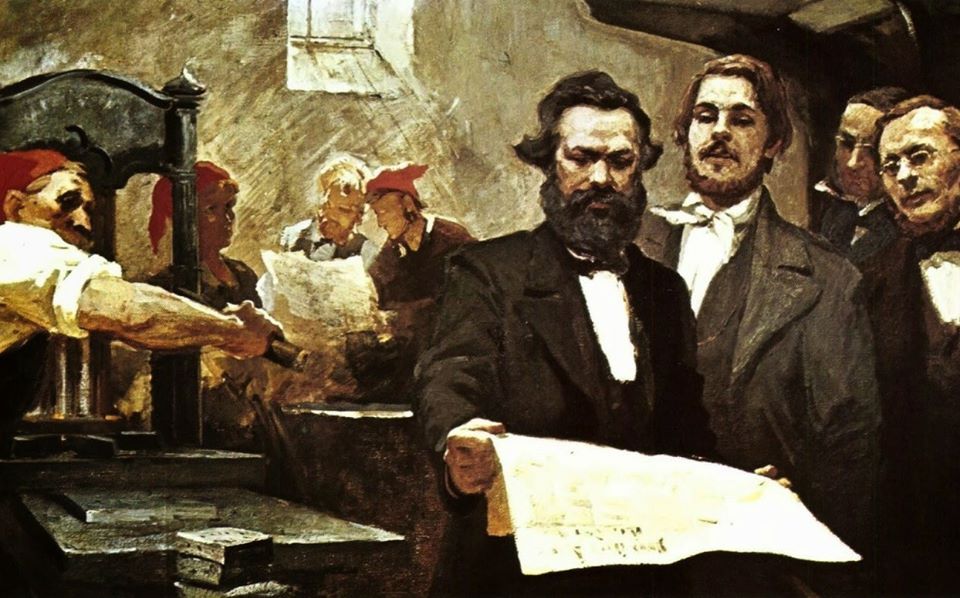

Marx and Engels were the philosophes of a second Enlightenment.

— Louis Menand

Enlightenment and the Young Marx

For Jonathan Israel, Marx’s status as a Radical Enlightenment figure ended prematurely in 1844. According to this interpretation, Marx was a Spinozistic liberal until he discovered the proletariat and converted to communism.1 But this sharp break that Israel assumes in Marx’s thinking did not occur. Israel provides only a cursory treatment of Marx’s writings after 1844 and never shows how Marx broke with the Enlightenment. This stark division between Enlightenment ideas and communism is arguably the worst part of his latest book, The Enlightenment That Failed. Israel implies that if only Marx had not collaborated with the bad Engels, but had stuck with the liberal Young Hegelians, he would have been saved from the economic “determinism” and “authoritarianism” that marred his later political career. Israel’s case for a counter-Enlightenment Marx ignores how earlier “Spinozistic” concerns and themes were integrated into his theory of communist revolution. Neither the “young Marx” nor the “old Marx” renounced humanism, naturalism, and the progressive ideas of Radical Enlightenment.

Israel mentions Marx’s father, Heinrich, in passing, but he neglects an entire backdrop of Marx’s Enlightenment-influenced childhood. This refers to the impact of Baron Ludwig von Westphalen, the privy councillor of Marx’s hometown of Trier and his future father-in-law. It is true that Heinrich Marx was a fan of Voltaire and Rousseau, but he was a fairly moderate liberal; it was in fact Ludwig who introduced the more radical aspects of the French Revolution to Marx, such as the utopian socialism of Henri de Saint-Simon. One other influence Israel ignores is that of Ludwig’s daughter and Marx’s future bride, Jenny von Westphalen. Four years his senior, and sometimes scandalously wearing a French tricolor in her hair, the young Jenny was key to Marx’s political development.2

As Israel notes, in order to practice law, Heinrich was forced to convert from Judaism to Lutheranism. Seven years after the defeat of the Grande Armée, Frederick William III revoked the civil emancipation of Jews that Napoleon had established in Trier. The emancipation of Jewish people was a conquest of the French Revolution, championed by Robespierre and Napoleon alike, and won the admiration of liberal elements in Germany. The revocation of Jewish emancipation affected not only the Marxes but also future associates of Karl such as the Hegelian law professor Eduard Gans and the poet Heinrich Heine. Heinrich Marx, Gans, and Heine were all pressured to civilly renounce Judaism.

After his conversion, Heinrich Marx continued to admire the French Enlightenment, and as a fellow liberal, he befriended Ludwig von Westphalen.3 Together, they were members of the Trier Casino Club, a club of bourgeois professionals with a liberal or left-wing bent. On one particular Bastille Day, the members spontaneously sang “La Marseillaise” in celebration. Little did they know that there was a Prussian spy in their midst, and once word reached the king about this rousing rendition of the subversive anthem, the club was unceremoniously shut down.

Soon after Karl began studying at university, he immersed himself in Hegelian philosophy. Heinrich feared the increasing radicalization of his son and believed that Karl’s path into philosophy would do him little good for his professional career. Once Marx told his father that he discovered Hegel in 1837, Heinrich all but despaired for his son’s prospects. Marx, however, ignored his father and delved deeper into the exciting world of Young Hegelianism.4

The two most important professors whom Marx had at the universities of Berlin and Bonn were Eduard Gans and Bruno Bauer. Gans was one of Hegel’s students, but after the July Revolution of 1830, Gans took Hegelianism in a republican and socialistic direction. Bauer was also a disciple of Hegel’s, and originally belonged to the Hegelian right; he favored orthodox Lutheranism and monarchism. But later, he transformed into a radical republican and a staunch critic of the Bible. Arnold Ruge christened Bauer the “Robespierre” of theology.5 From these teachers, Marx absorbed Hegelian philosophy and democratic republicanism.

Enlightenment and the Young Engels

Growing up in different circumstances, the young Friedrich Engels was raised by strict conservative Pietists. The wealthy Engels family was based in Wuppertal, and his father, Friedrich Sr., owned textile factories as part of the firm Ermen & Engels. Young Friedrich gradually shook off the traditional religious beliefs of his parents and converted to atheistic Hegelianism after reading David Strauss’s The Life of Jesus (1835–36). Strauss was one of the first left Hegelians, combining Hegel’s philosophy with Enlightenment rationalism. He argued that the Gospels were not literal histories but mythopoetic illustrations of the human condition. Jesus was not the son of God but a poetic representation of humanity’s own infinite worth.6

After beginning military service in Berlin, Engels joined forces with the Young Hegelians. He frequented the Hippel café, where Bauer and others would drink and converse. Engels liked to draw funny caricatures of their rowdy philosophical debates,7 and he even wrote a bombastic epic poem about Young Hegelianism, entitled “The Insolently Threatened yet Miraculously Rescued Bible.” There, Engels portrays the Young Hegelians as more dangerous than the Jacobin Club and refers to himself by his new Jacobin alias, Oswald:

Right on the very left, that tall and long-legged stepper

Is Oswald [Engels], coat of grey and trousers shade of pepper;

Pepper inside as well, Oswald the Montagnard;

A radical is he, dyed in the wool, and hard.

Day in, day out, he plays upon the guillotine a

Single solitary tune and that’s a cavatina,

The same old devil-song; he bellows the refrain:

Formez vos bataillons! Aux armes, citoyens!

[Form your battalions! To arms, citizens! — from the Marseillaise]8

Marx knew Engels in 1842 but did not think much of him at the time. Two years later, however, when they reencountered each other in Paris, they recognized that they shared the same fundamental worldview and thus began a lifelong friendship and collaboration as communists. Engels was the first to accept communism through the work of Moses Hess. From his experiences with the Parisian working class and after reading Engels’s Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy (1843), Marx embraced communism in turn. In another essay written in the same year, Engels deduces socialism as the logical result of British economics, the French Revolution, and German philosophy:

The English came to the [socialist] conclusion practically, by the rapid increase of misery, demoralisation, and pauperism in their own country: the French politically, by first asking for political liberty and equality; and, finding this insufficient, joining social liberty, and social equality to their political claims: the Germans became Communists philosophically, by reasoning upon first principles. This being the origin of Socialism in the three countries.9

Marx repeats this European trinity of British economics, French politics, and German philosophy in his writings from 1844: “It must be granted that the German proletariat is the theoretician of the European proletariat just as the English proletariat is its economist and the French its politician.”10 With this new communist worldview, Marx and Engels attempted to settle their philosophical debts with the Young Hegelians. In doing so, they took up the philosophy of Ludwig Feuerbach, which combined materialism, empiricism, and humanism.

The Holy Family

Making their Feuerbachian debut together in The Holy Family (1845), Marx and Engels saw Feuerbach’s materialism as repeating the Enlightenment’s battle against metaphysical abstractions. As Hegel put it in The Phenomenology, Enlightenment liberated itself from any metaphysical rationalism, emphasizing what’s finite and concrete over what’s theological and abstract. In The Holy Family, Marx and Engels saw Hegel himself as the German repetition of 17th-century rationalism (e.g., Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Malebranche), while Feuerbach represented the return to the Enlightenment of Holbach, Helvétius, and Bentham. According to Marx and Engels, Feuerbach had finally exorcised the ghost of metaphysics once and for all, and now all philosophy had to go through the “fire bath” of Feuerbach. As Marx put it once earlier, “There is no other road for you to truth and freedom except that leading through the brook of fire (the Feuerbach). Feuerbach is the purgatory of the present times.”11

But even in their criticism of Spinoza as a rationalist metaphysician, Marx and Engels maintained a materialist basis. In The Holy Family, they affirm a materialist monism, that “body, being, substance, are but different terms for the same [material] reality. It is impossible to separate thought from matter that thinks. This matter is the substratum of all changes going on in the world.”12 But, in contrast to Bauer and to Israel, Marx and Engels in The Holy Family trace the impact of John Locke’s empiricism on French materialism. It is true, as Israel has pointed out, that Spinozism was an important philosophical component of the Radical Enlightenment; nevertheless, Lockean epistemology had radical implications for philosophers on the Continent as well.13

The Holy Family criticizes the elitism of the Young Hegelians, where Bauer merely echoes the unhistorical conception of human progress that pits a disembodied reason against the spirit of reaction. For Marx, progress advances from social contradictions, and the masses themselves are the bearers of this progress. The masses are the most important factor in Enlightenment, and this process of Enlightenment is inseparable from class struggle.14 The question of the masses is central to Marx and Engels’ critique of Bauer. Bauer saw philosophical criticism as a task directed against the ignorant masses; for him, the lofty fight for self-consciousness and liberty was antagonistic to the crude material interests of the crowd. As one reviewer of The Holy Family wrote, satirizing Bauer’s own elitism, “To get rid of the French Revolution, communism, and Feuerbach, he [Bruno Bauer] shrieks “masses, masses, masses!,” and again: “masses, masses, masses!”15

For Marx and Engels, the two main sources of French materialism were Lockean epistemology and Cartesian natural science. “The two trends intersect in the course of development,” giving birth to the more refined and sophisticated materialism of Holbach and Helvétius. This materialism, however, contains a dialectic within itself, one that points beyond bourgeois society. From the philosophical claims of materialism, the authors deduce the political conclusion of communism. It is worth quoting The Holy Family at length here, since Israel argues that Marx stopped his association with Radical Enlightenment in 1844. But in 1845, Marx and Engels assert the contrary:

French materialism leads directly to socialism and communism. There is no need for any great penetration to see from the teaching of materialism on the original goodness and equal intellectual endowment of men, the omnipotence of experience, habit and education, and the influence of environment on man, the great significance of industry, the justification of enjoyment, etc., how necessarily materialism is connected with communism and socialism. If man draws all his knowledge, sensation, etc., from the world of the senses and the experience gained in it, then what has to be done is to arrange the empirical world in such a way that man experiences and becomes accustomed to what is truly human in it and that he becomes aware of himself as man. If correctly understood interest is the principle of all morality, man’s private interest must be made to coincide with the interest of humanity.16

Here, Marx and Engels take up key Enlightenment tenets, including the essential goodness of human nature (i.e., the rejection of original sin); the importance of education and environment; the “great significance” of industry; and hedonistic ethics, or what they call “the justification of enjoyment.” These are the principles that any socialism must defend for it to make philosophical sense. Again, Israel’s stark demarcation between Enlightenment and Marx’s communism is belied by such passages.

Without the backbone of these Radical Enlightenment premises, the struggle for social equality would be meaningless. Marx and Engels affirm equality as,

man’s consciousness of himself in the element of practice, i.e., therefore, man’s consciousness of other men as his equals and man’s relation to other men as his equals. Equality is the French expression for the unity of human essence, for man’s consciousness of his species and his attitude toward his species, for the practical identity of man with man, i.e., for the social or human relation of man to man.17

In other words, equality is the social expression of our common human identity. It serves as the basis for criticizing the dehumanizing economic relations that pit human beings against each other.

The German Ideology

In The German Ideology (1845-6), written shortly after The Holy Family, Marx and Engels criticize Feuerbach for being insufficiently materialist, since he, like the French materialists before him, was an idealist when it came to history. In this domain, Feuerbach still privileges ideas over material reality. The German Ideology is where the authors first clearly articulate the materialistic conception of history, which is marked by a series of different modes of production. The products of consciousness such as law, religion, and philosophy are all conditioned by material circumstances. Such a theory of history in particular explains how French materialism is a necessary outgrowth of the bourgeoisie’s struggles against feudalism.18

The German Ideology acknowledges what Hegel had already discovered in The Phenomenology: that the spirit of Enlightenment came about through emerging bourgeois conditions. The truth of Enlightenment was “utility,” and utilitarianism was the philosophy of the radical French bourgeoisie. Before the consolidation of capitalism, philosophers like Holbach and Helvétius did not carefully distinguish human flourishing from economic competition and exploitation. Bourgeois reality was assumed to be the natural order of things. According to Marx, this idealized conception was a necessary and justified illusion, without which there would be no ideological motivation for the bourgeois revolution. But there is a darker side to bourgeois Enlightenment, of what Hegel called “the spiritual animal kingdom.” Beneath the idealistic image of human flourishing lurked the dehumanized relations of commodity exchange.

In The Holy Family, Marx and Engels extracted the communist kernel from the shell of bourgeois Enlightenment, meaning a transition from Helvétius and Holbach to the utopian socialism of Gracchus Babeuf and Charles Fourier. Here, in The German Ideology, the authors focus on the illusion of bourgeois Enlightenment, which could not fulfill the promise of human flourishing. While Helvétius and Holbach represent the bourgeoisie in its heroic and more universal phase, Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill represent the philosophical conscience of a cynical bourgeoisie that has resigned itself to the reality of exploitation. For the latter, human flourishing is fully identified with market relations.

The Communist Manifesto

Nonetheless, as jaded as bourgeois Enlightenment can be, there is something refreshing about its rejection of feudalism. Repeating what Hegel argued in The Phenomenology, Marx and Engels see bourgeois reality as achieving a relative kind of Enlightenment. As Marx and Engels put it famously in The Communist Manifesto (1848): “All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.”19 The enlightened bourgeoisie “has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation.”20 This description of feudal culture’s demise was strongly foreshadowed in the pages of Hegel’s Phenomenology and its discussion of Rameau’s Nephew.21

In the Manifesto, Marx and Engels not only praise the bourgeoisie for uniting the world economy; they also acknowledge the democratic “representative state” as its most important political achievement. Not just the (partial) liberation of the productive forces, but liberal ideas like freedom of conscience, equality before the law, and freedom of the press are legitimate gains for humanity. Political equality, however, is insufficient without economic equality. The bourgeoisie achieved Enlightenment only halfway since it clings to a superstitious belief in private property. Thus the bourgeoisie cannot complete its own Enlightenment, since a truly human and secular society is incompatible with class relations.22

In the third chapter of the Manifesto, Marx and Engels attack what they call feudal socialism and “true socialism.” Both of these false socialisms are reactionary, insofar as they advocate romantic solutions to capitalism. The feudal socialist wants workers to return to an imagined organic aristocratic society, in which they will resubmit to their noble betters. On the other hand, the “true socialist” wants to push aside class struggle in favor of a classless humanitarianism. Such ethical idealism denounces bourgeois society in toto as sinful and irredeemable. While the “true socialists” think they are moving past bourgeois society, they inadvertently adopt the romantic critique of capitalism. For Marx and Engels, one cannot achieve socialism without presupposing the accomplishments of bourgeois society and bourgeois enlightenment.

True socialism “forgot, in the nick of time, that the French [socialist] criticism, whose silly echo it was, presupposed the existence of modern bourgeois society, with its corresponding economic conditions of existence, and the political constitution adapted thereto, the very things those attainment was the object of the pending struggle in Germany.”23 In their absolute rejection of everything progressive in bourgeois society, including constitutional law, true socialism gives aid to reaction. Presupposing the advancement of science and industry, socialism not only liberates the productive forces; it also consummates the struggle for democracy. Socialism does not simply cast off the forms of democracy and republicanism, but makes democracy real for the working class.

The Dead Dogs

As Marx matured in his economic thinking, he returned to Hegelian dialectics as the basis for his critique of capitalism. In a letter to Ludwig Kugelmann, he accuses Feuerbach, along with the rest of the German intelligentsia, of treating Hegel like a “dead dog.”24 According to Marx, one must extract the rational side of Hegel’s dialectics and discard its irrational idealism. It is no coincidence that when Marx defends Hegel in his afterword to the first volume of Capital (1867), he compares Hegel’s fate with that of Spinoza’s. If the German Enlightenment stunted itself in treating Spinoza as a “dead dog,” then the same goes for Eugen Dühring and others when they treat Hegel as a mere mystic.25

Marx’s approach to Spinoza and Hegel is itself dialectical. As he puts it in a letter to Ferdinand Lassalle, “Even in the case of philosophers who give systematic form to their work, Spinoza for instance, the true inner structure of the system is quite unlike the form in which it was consciously presented by him.”26

Spinoza is not absent in Marx’s Grundrisse (1859) and Capital. Marx wrote his critique as a “natural history,” wherein he laid bare the economic law of motion for the capitalist system. This presupposes a Spinozistic outlook of paying attention to rational causes over mere appearances: “Vulgar economy which, indeed, ‘has really learnt nothing,’ here as everywhere sticks to appearances in opposition to the law which regulates and explains them. In opposition to Spinoza, [political economy] believes that ‘ignorance is a sufficient reason.’” 27 Not only does Marx assume Spinoza’s materialism of causation; like Hegel, he also accepts Spinoza’s insight that all determination is negation; that it is not enough to negate something, but to overcome that negation in turn. Negation is determined not just by particular things, but by an overall process, or what Marx refers to as “the negation of the negation.” For Marx, Spinoza provides the philosophical basis for this dialectical logic: “This identity of production and consumption amounts to Spinoza’s thesis: determinatio est negatio.”28 Needless to say, this reemergence of Spinozism as integral to Marx’s critique refutes Israel’s argument that the later Marx abandoned Spinozism.

Marx and Engels’ Second Enlightenment

In the Grundrisse, Marx takes issue with bourgeois socialists, who merely affirm the ideals of the French Revolution, while ignoring the realities of capitalism. In pursuing liberty, equality, and fraternity one-sidedly, these socialists ironically reinforce unfreedom, inequality, and atomization. This is because they do not understand the reality of competition and exchange, and fall prey to its logic. This is certainly the case for Marx when he discusses the petty bourgeois socialism of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and his followers.29 As Marx puts it in Capital, “There alone rule [in bourgeois society] Freedom, Equality, Property and Bentham,” where the name of Bentham signifies the crass logic of exploitation.30

Seemingly strange bedfellows, both Israel and the structuralist Marxist Louis Althusser claim that the later Marx abandoned his original humanism. But the evidence in the mature economic manuscripts is clear. Marx reaffirms that socialism will be a realm of freedom based on an advanced material economic base. The realm of necessity will not be abolished but workers will “rationally” regulate “their interchange with Nature, bringing it under their common control, instead of being ruled by it as by the blind forces of Nature.”31 The realm of freedom will “blossom forth only with this realm of necessity as its basis. The shortening of the working-day is its basic prerequisite.”32 In socialism, humanity will live “under conditions most favourable to, and worthy of, their human nature.”33

The interrelation between humanity and nature, a Spinozistic point, is an echo of what Marx and Engels previously wrote decades before in The Holy Family: “If man is shaped by his surroundings, his surroundings must be made human. If man is social by nature, he will develop his true nature only in society, and the power of his nature must be measured not by the power of separate individuals but by the power of society. This and similar propositions are to be found almost literally even in the oldest French materialists.”34 These passages from The Holy Family and Capital show continuity in Marx’s Enlightenment humanism.

In his separate works, Engels celebrates the thinkers of the Enlightenment. Diderot and Rousseau are credited for inventing modern dialectics in their respective criticisms of bourgeois society and property relations. But the entirety of the French Enlightenment comes in for special praise in his Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy (1886): “The French materialists no less than the deists Voltaire and Rousseau held this conviction [of historical progress] to an almost fanatical degree, and often enough made the greatest personal sacrifices for it. If ever anybody dedicated his whole life to the ‘enthusiasm for truth and justice’ — using this phrase in the good sense — it was Diderot, for instance.”35

In Anti-Dühring (1877), Engels calls Spinoza “a dialectician,” and in Dialectics of Nature (1883), he affirms Spinoza’s idea of a self-caused substance as expressing the activity of matter in motion, that is, as anticipating dialectical materialism. 36 In an anecdote, Plekhanov recounts how Engels told him that “old Spinoza” was “absolutely right” to see mind and matter as two sides of one nature. In contrast to Israel, Plekhanov unequivocally states, “I am fully convinced that Marx and Engels, after the materialist turn in their development, never abandoned the standpoint of Spinoza.”37

According to Engels, it was the radical bourgeoisie that originally developed the modern idea of equality. This idea was “first formulated by Rousseau, in trenchant terms but still on behalf of all humanity.”38 The emerging proletariat, however, went deeper than the bourgeoisie in adopting equality under its revolutionary banner, and as “was the case with all demands of the bourgeoisie, so here too the proletariat cast a fateful shadow beside it and drew its own conclusions (Babeuf). This connection between bourgeois equality and the proletariat’s drawing of conclusions should be developed in greater detail.”39 Hence, we see that proletarian morality for Engels is not the total negation of bourgeois Enlightenment morality, but its dialectical negation. Political equality is insufficient and needs social equality to be made substantive and permanent.

The Critique of the Gotha Program

This leads us to Marx’s conception of equality in The Critique of the Gotha Program (1875). Under the banner of social equality, the proletariat establishes its rule. But, according to Marx, during the first phase of communism (i.e., socialism), the right to equality still presupposes inequality. How is this possible? In this initial stage, the productive forces still need to be reorganized and further developed. Socialism frees society from the domination of what Marx called “the law of value” (i.e., commodity relations), but it cannot totally do away with principles of exchange. For the sake of developing the productive forces, the first phase of communism is governed by the principle from each according to their ability, to each according to their deed. This means that “as far as the distribution of [the means of consumption] among the individual producers is concerned, the same principle prevails as in the exchange of commodity equivalents: a given amount of labor in one form is exchanged for an equal amount of labor in another form…The right of the producers is proportional to the labor they supply; the equality consists in the fact that measurement is made with an equal standard, labor.”40

Under this first phase of communism, it does not recognize class differences, but it does recognize differences when it comes to what workers can contribute. Some workers, either physically or mentally, will contribute more than others, and they may need more compensation than others because of their particular circumstances. Perhaps they have to take care of more dependents, or they have a greater skill set. Regardless, Marx is clear that a kind of exchange still exists under socialism.

Only in the upper stage of socialism, namely communism proper, does exchange value completely wither away in favor of use value. Hegel had already seen the contradictory nature of value in his analysis of the bourgeois Enlightenment. The truth of bourgeois Enlightenment for Hegel was utility, a contradictory phenomenon that expressed both the promise of human flourishing and the reality of exploitation. Utility was bound up with the commodity form, in which use-value is dominated by market exchange. But for Marx, only full communism can liberate use value from exchange value, thus resolving the main contradiction of bourgeois Enlightenment. Thus, communism is not the abstract negation, but the completion of the Enlightenment project. This completion is summed up in the slogan: “From each according to their ability, to each according to their needs!”41

Under communism, equality is understood as a law of proportion — that all human beings have a right to equal development and satisfaction of their different needs. Helen Macfarlane, the Chartist radical and first translator of The Communist Manifesto into English, put it as follows: “The Rights of one human being are precisely the same as the Rights of another human being, in virtue of their common nature.”42 Without this common human nature, Marx’s slogan for the realization of human wants is unintelligible and unachievable. This slogan is at one with Macfarlane’s translation of the Manifesto’s statement that the “old Bourgeois Society, with its classes, and class antagonisms, will be replaced by an association, wherein the free development of EACH is the free development of ALL.”43

Whether it is Spinozism, French materialism, or the ideas of the French Revolution — particularly the idea of equality — Marx and Engels were no strangers to Radical Enlightenment. On the contrary, they were its most advanced representatives. We have demonstrated that Radical Enlightenment was not just a passing phase of Marx’s youth but the consistent philosophical thread throughout his thinking.

Part V of this series on the Enlightenment will appear next Sunday.

Notes

1. ↑ “Marx’s early thought, shaped by Bauer and Feuerbach, was in a sense a variant of Spinozist materialism, naturalism, anti-providentialism, and anti-Scriptualism which, before long, became dramatically infused with zeal for democratic transformation.” Jonathan I. Israel, Enlightenment that Failed, 905.

This ignores Bauer’s explicit anti-Spinozism, which favored self-consciousness over substance, as well as Feuerbach’s empiricist critique of Spinoza as a metaphysician. Marx himself in his dissertation repeats Bauer-like criticisms of Spinoza, while in later works, such as The Holy Family, he repeats Feuerbach’s critique. Israel does not deign to comment on Marx’s criticisms of Spinoza in this early period.

2. ↑ Harrison Fluss and Sam Miller, “Subversive Beginnings,” Jacobin, June 19, 2016; Harrison Fluss and Sam Miller, “The Life of Jenny Marx,” Jacobin, February 14, 2016.

3. ↑ For more on Heinrich Marx’s opinions on the French Revolution and Napoleon, see Michael Heinrich, Karl Marx and the Birth of Modern Society: The Life of Marx and the Development of His Work, vol. 1: 1818–1841 (New York: Monthly Review, 2019), 81–82.

4. ↑ The young Marx was into dueling, drinking, and, now, Hegel. In Berlin, a group of Young Hegelians met at Hippel’s café, calling themselves the Berlin Frei. There they drank and vigorously argued, celebrating not just free thought but free spirits. When the future anarchist Mikhail Bakunin visited Berlin in its Young Hegelian heyday, he liked to play a philosophical drinking game:

In Russia, the young Bakunin became a member of a literary group so intoxicated with Hegelian idealism that even their love affairs were permeated by it, and who, volatilizing in the Russian way the portentous abstractions of the German, used to toast the Hegelian categories, proceeding through the metaphysical progression from Pure Existence to the divine Idea.

Edmund Wilson, To the Finland Station: A Study in the Writing and Acting of History (New York: New York Review of Books, 2003), 262.

5. ↑ David Leopold, The Young Karl Marx: German Philosophy, Modern Politics, and Human Flourishing (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 103.

6. ↑ Marilyn Chapin Massey, Christ Unmasked: The Meaning of the Life of Jesus in German Politics (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983); and Friedrich Engels, Letters of the Young Engels (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1976).

7. ↑ For Engels’s drawings, see “Die Freien by Friedrich Engels,” Wikipedia Commons.

8. ↑ “The Insolently Threatened Yet Miraculously Rescued Bible,” in MECW, vol. 2, 335.

9. ↑ “Progress of Social Reform on the Continent,” in MECW, vo. 3, 392–93.

Later in the same article, the young Engels inferred that the premises of German philosophy lead to the conclusion of communism:

Our party has to prove that either all the philosophical efforts of the German nation, from Kant to Hegel, have been useless — worse than useless; or, that they must end in Communism; that the Germans must either reject their great philosophers, whose names they hold up as the glory of their nation, or that they must adopt Communism. (Ibid., 406.)

Lenin also popularized Marxism as a synthesis of British economics, French politics, and German philosophy:

The Marxist doctrine is omnipotent because it is true. It is comprehensive and harmonious, and provides men with an integral world outlook irreconcilable with any form of superstition, reaction, or defence of bourgeois oppression. It is the legitimate successor to the best that man produced in the nineteenth century, as represented by German philosophy, English political economy and French socialism. (“The Three Sources and Three Component Parts of Marxism,” 1913, in Lenin Collected Works [henceforth LCW], vol. 19 [Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1974], 23–24.)

Before Marx and Engels, Hess was the first to conceive of this progressive trinity of England, France, and Germany in his European Triarchy (1841), wherein he claimed that Spinoza represents “the ideal foundation of modern times.” Four years before he wrote this work, Hess had announced in The Holy History of Mankind (1837) that humanity had entered into the Age of Spinoza.

10. ↑ “Critical Notes on the Article: ‘The King of Prussia and Social Reform. By a Prussian,’” in MECW, vol. 3, 202.

11. ↑ Karl Marx, “Luther as the Arbiter between Strauss and Feuerbach,” in Writings of the Young Marx on Philosophy and Society, ed. L. D. Easton and K. H. Guddat (New York: Doubleday, 1967), 95.

12. ↑ The Holy Family, in MECW, vol. 4, 129.

The relationship between Feuerbach and Spinoza is unfortunately outside the scope of this series. The scholar Marx W. Wartofsky, however, explains that Feuerbach saw himself as a legatee of Spinoza’s pantheism and materialism: “Thus, Feuerbach contrasts pantheism, as the theoretical negation of theology, with empiricism, as the practical negation of theology. But he says pantheism — that is, Spinoza’s pantheism, which accords matter divine status, albeit abstractly and metaphysically — as the legitimation and sanction of the “materialistic tendency of modern times.’” Feuerbach (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977), 370.

13. ↑ Joseph de Maistre, in his St. Petersburg Dialogues, engages in a long rant against Lockeanism. In the sixth dialogue, by denying the doctrine of innate ideas, Locke is called an enemy of Christian authority, and Maistre despairs that so many French philosophers fell under Locke’s spell. They neglected their own “Christian Plato” (Malebranche) in favor of English empiricism. Joseph de Maistre, St Petersburg Dialogues: Or Conversations on the Temporal Government of Providence (London: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993), 187, 188.

14. ↑ According to Lukács, during the Restoration period, defenders of human progress redefined Enlightenment as inextricably bound up with mass struggle:

According to the new interpretation the reasonableness of human progress develops ever increasingly out of the inner conflict of social forces in history itself; according to this interpretation history itself is the bearer and realizer of human progress. The most important thing here is the increasing historical awareness of the decisive role played in human progress by the struggle of classes in history. The new spirit of historical writing, which is most clearly visible in the important French historians of the Restoration period, concentrates precisely on this question: on showing historically how modem bourgeois society arose out of the class struggles between nobility and bourgeoisie, out of class struggles which raged throughout the entire ‘idyllic Middle Ages’ and whose last decisive stage was the great French Revolution. These ideas produce the first attempt at a rational periodization of history, an attempt to comprehend the historical nature and origins of the present rationally and scientifically.

(Georg Lukács, The Historical Novel (London: Merlin Press, 1989), 27–28.)

15. ↑ Massimiliano Tomba, Marx’s Temporalities (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 22.

16. ↑ The Holy Family, in MECW, vol. 4, 130.

17. ↑ Ibid., 39.

18. ↑ The German Ideology is frequently described as a work that treats philosophy as a mere epiphenomenon of material class relations, or as simply bourgeois mysticism. But in their polemic against Max Stirner, Marx and Engels defend certain philosophers for their progressive contributions to humanity. This includes praise for the Stoic tradition and for Epicurus as a radical Enlightener: “Epicurus…was the true radical Enlightener of antiquity; he openly attacked the ancient religion, and it was from him, too, that the atheism of the Romans, insofar as it existed, was derived. For this reason, too, Lucretius praised Epicurus as the hero who was the first to overthrow the gods and trample religion underfoot.” The German Ideology, in MECW, vol. 5, 141–42. As we can see, Israel even ignores Marx’s own use of the phrase radical Enlightenment.

19. ↑ Manifesto of the Communist Party, in MECW, vol. 6, 487.

20. ↑ Ibid.

21. ↑ For Hegel’s discussion of Diderot, see Hegel, Enlightenment, and Revolution.

22. ↑ In On the Jewish Question (1843), Marx pointed out that abstract rights to property and religion presupposed an unequal and alienated society. Any society in which private property and religion predominate, such as in the United States, is not a truly humanized one, but still alienated. While political emancipation is certainly an achievement, it is not enough if it stays at the political level and ignores the so-called private realm of civil society. Thus, the problem is not that American society is secular, but since it rests on an alienated bourgeois reality, it is not secular enough. See “On the Jewish Question,” in MECW, vol. 3, 146–47.

23. ↑ Manifesto, 512.

Around the time of the Manifesto, Marx also wrote,

The workers know that the abolition of bourgeois property relations is not brought about by preserving those of feudalism. They know that the revolutionary movement of the bourgeoisie against the feudal estates and the absolute monarchy can only accelerate their own revolutionary movement. They know that their own struggle against the bourgeoisie can only dawn with the day when the bourgeoisie is victorious. Despite all this they do not share Herr Heinzen’s bourgeois illusions. They can and must accept the bourgeois revolution as a precondition for the workers’ revolution. However, they cannot for a moment regard it as their ultimate goal.

(“Moralising Criticism and Critical Morality,” in MECW, vol. 6, 332–33.)

We will address how Marx changes his position on the proletariat’s relationship to bourgeois revolutions in part six of this series. Suffice it to say, following the failure of the bourgeoisie to lead revolutions on the Continent in 1848, Marx argues that the proletariat cannot simply wait for the bourgeoisie to fulfill its original democratic tasks. By the 1840s, the heroic phase of bourgeois revolutions was over, and the proletariat must now play the leading revolutionary role; it must fight not only for the older tasks of democracy, but for socialism. Hence, after the failed struggles of 1848, Marx disavows a stagist conception of revolution, committing himself to a politics of permanent revolution. On the history and politics of permanent revolution, see Neil Davidson’s How Revolutionary Were the Bourgeois Revolutions?

It is interesting to note that Davidson himself uses the phrase “radicalized Enlightenment” to describe Marx and Engels’s socialist transformation of the bourgeois Enlightenment in the Manifesto: “From these doubts [about bourgeois society] came the radicalized Enlightenment at the heart of Marxism.” Neil Davidson, How Revolutionary Were the Bourgeois Revolutions? (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012), 655.

24. ↑ “Marx to Kugelmann. 27 June 1870,” in MECW, vol. 43, 528.

25. ↑ In the afterword to the second German edition of Capital, Marx said,

The mystifying side of Hegelian dialectic I criticised nearly thirty years ago, at a time when it was still the fashion. But just as I was working at the first volume of “Das Kapital,” it was the good pleasure of the peevish, arrogant, mediocre ‘Epigonoi who now talk large in cultured Germany, to treat Hegel in same way as the brave Moses Mendelssohn in Lessing’s time treated Spinoza, i.e., as a “dead dog.” I therefore openly avowed myself the pupil of that mighty thinker, and even here and there, in the chapter on the theory of value, coquetted with the modes of expression peculiar to him. The mystification which dialectic suffers in Hegel’s hands, by no means prevents him from being the first to present its general form of working in a comprehensive and conscious manner. With him it is standing on its head. It must be turned right side up again, if you would discover the rational kernel within the mystical shell.

(Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 1, in MECW, vol. 35, 19.)

26. ↑ “Marx to Lassalle. 31 May 1858,” in MECW, vol. 40, 316.

27. ↑ Capital, vol. 1, in MECW, vol. 35, 311.

28. ↑ Karl Marx, Grundrisse, trans. Martin Nicolaus (New York: Vintage Books, 1973), 90.

29. ↑ Ibid., 248.

30. ↑ Capital, vol. 1, in MECW, vol. 35, 186. In a footnote to Capital, Marx contrasts Bentham — that “genius of bourgeois stupidity” — unfavorably with the more sophisticated French materialists. Marx does not dismiss the category of utility but argues that one cannot derive an adequate conception of human nature from utility alone: “The principle of utility was no discovery of Bentham. He simply reproduced in his dull way what Helvétius and other Frenchmen had said with esprit in the 18th century. To know what is useful for a dog, one must study dog-nature. This nature itself is not to be deduced from the principle of utility. Applying this to man, he that would criticise all human acts, movements, relations, etc., by the principle of utility, must first deal with human nature in general, and then with human nature as modified in each historical epoch.” Ibid., 605.

31. ↑ Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 3, in MECW, vol. 37, 807.

32. ↑ Ibid.

33. ↑ Ibid.

34. ↑ The Holy Family, in MECW, vol. 4, “131.

35. ↑ Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy, in MECW, vol. 26, 373.

36. ↑ “Reciprocal action is the first thing that we encounter when we consider matter in motion as a whole from the standpoint of modern natural science. We see a series of forms of motion, mechanical motion, heat, light, electricity, magnetism, chemical compound and decomposition, transitions of states of aggregation, organic life, all of which, if at present we still make an exception of organic life, pass into one another, mutually determine one another, are in one place cause and in another effect, the sum-total of the motion in all its changing forms remaining the same (Spinoza: substance is causa sui strikingly expresses the reciprocal action).” The Dialectics of Nature. Fragments and Notes, in MECW, vol. 25, 511.

37. ↑ Georgi Plekhanov, “Bernstein and Materialism,” Marxists Internet Archive.

38. ↑ “Preparatory Writings for Anti-Dühring,” in MECW, vol. 25, 603.

39. ↑ Ibid.

40. ↑ Critique of the Gotha Programme, in MECW, vol. 24, 86.

41. ↑ Ibid., 87. According to Eric Hobsbawm, the phrase “From each according to their ability, to each according to their needs!” was originally a Saint-Simonian one. Eric Hobsbawm, How to Change the World: Reflections on Marx and Marxism, 29–30.

While Saint-Simon himself eschewed the Jacobin Terror, he defended the achievements of the French Revolution, and his conception of history and utopian socialism built on Enlightenment ideas. According to the Marxist historian Samuel Bernstein, “Saint-Simon set himself the objective of founding the science of man. He desired to follow in the tradition of Newton, and he conceived of science as organized and directed toward the improvement of mankind. Equally with other great Utopians, he looked to those in power for the fulfillment of his dream.” Samuel Bernstein, “Saint-Simon’s Philosophy of History,” Science & Society 12, no. 1 (Winter 1948): 85.

In Louis Blanc’s speech of 1848 (“A Community of Labor”), we find an early popularization of the slogan that Marx would adopt. The French reformist said, “The ideal toward which humanity must proceed is the following: to produce according to its powers, to consume according to its needs” [authors’ translation]. The original French reads, “L’idéal vers lequel la société doit se mettre en marche est donc celui-ci: produire selon ses forces, consommer selon ses besoins.” Louis Blanc, Pages d’histoire de la Révolution de Février, 1848 (Paris: Imprimerie et Librairie de V Wouters, 1850), 217.

42. ↑ Helen Macfarlane, Red Republican (London: Unkant Press, 2014), 66–67.

43. ↑ Ibid., 139.

This is a Guest Post. Guest Posts do not necessarily reflect the views of the Left Voice editorial board. If you would like to submit a contribution, please contact us.

Tags: History