Authoritarian Ireland and the Secular Apocalypse

Book Review of Prophet Song by Paul Lynch

In his book, How The Irish Saved Civilization: The Untold Story of Ireland’s Heroic Role from the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe, Thomas Cahill shows how the Irish monks maintained European culture during the dark ages when Rome was sacked by Visigoths and its empire collapsed. In the subsequent chaos and illiteracy, symbolism took over from analysis. Cahill writes:

The intellectual disciplines of distinction, definition, and dialectic that had once been the glory of men like Augustine were unobtainable by readers of the Dark Ages, whose apprehension of the world was simple and immediate, framed by myth and magic. A man no longer subordinated one thought to another with mathematical precision; instead, he apprehended similarities and balances, types and paradigms, parallels and symbols. It was a world not of thoughts, but images. Even the “Romans” at Whitby presented their point of view in the new way. They did not argue, for genuine intellectual disputation was beyond them. They held up pictures for the mind – one set of bones versus another. (p. 204)

One thousand years later as the symbolism of the Dark ages and medievalism waned, a new movement arose to replace it: Romanticism. In the Romanticist outlook, passion and intuition determined our understanding of the world combined with themes of isolation and loneliness, and a delight in horror and threat. Beauty became about strong emotional responses and not about form. The Romanticists rejected Enlightenment Era artists who, like the Irish monks, were interested in ideas and thoughts, and who used them to depict and critique social relations.

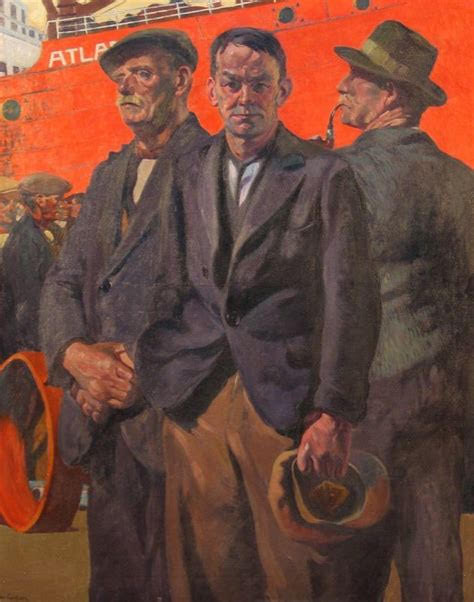

Dockers (1934) by Maurice MacGonigal

Dockers (1934) by Maurice MacGonigal

Unfortunately, Romanticism is a movement that is not only dominant in the production of culture but is also favoured by the institutions of commendation. One such institution is the Booker Prize for literature, and a good example is the 2023 winner, Prophet Song, a dystopian novel by the Irish author Paul Lynch:

The novel depicts the struggles of the Stack family, including Eilish Stack, a mother of four who is trying to save her family as the Republic of Ireland slips into totalitarianism. The narrative is told unconventionally, with no paragraph breaks.

As we always love to reference James Joyce here in Ireland, we could argue that this paragraphless state of Prophet Song is influenced by the Molly Bloom soliloquy at the end of Ulysses, which was radical for its time in having no punctuation. (Indeed, Eilish Stack’s daughter is called Molly).

Furthermore the style of Prophet Song, in general, is similar to Molly Bloom’s stream of consciousness in that we get, merged together, Eilish’s thoughts, worries and utterances.

Throughout the novel we also get, in a staccato rhythm, brief descriptions of the coercive actions of the state as it faces the growing opposition of a resistance movement that strengthens and spreads countrywide.

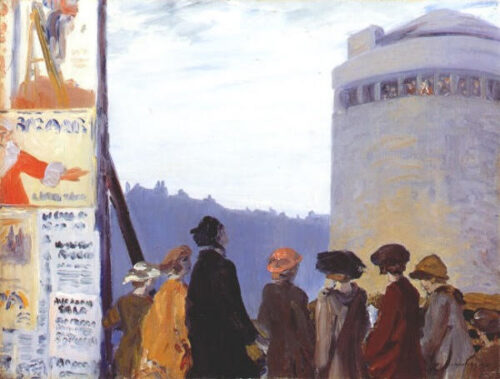

Communicating With Prisoners (1924) by Jack Butler Yeats (1871–1957)

Communicating With Prisoners (1924) by Jack Butler Yeats (1871–1957)

From the off, the dark terror commences with knocking at her door which reveals two men ‘almost faceless in the dark'(p. 1). The increasingly fascisitic Irish state is shown through the imprisonment of her trades’ union husband (p. 29), an Emergency Powers Act (p. 53), government controls on judiciary (p. 58), national service (p. 73), unmarked cars pulling up silently (p. 76), foreign media internet blackout (p. 175), and the government closing the schools (p. 183).

The rebels, on the other hand, are really not that much different. And this is the crux of the issue. There has always been a large gap between the Romantic heroes and working class heroes. In Romanticism the ‘resistance’ or ‘rebels’ are often ‘rejected by society’ with various combinations of introspection, wanderlust, melancholy, misanthropy, alienation, and isolation.

And even though “the worm is turning” (p. 147), and the armed insurrection growing (p. 130) the violence is abstracted into terrorism (p. 160), and Eilish “is overcome by loathing, seeing not men but shadows parading the day born from darkness, seeing how they have made an end of death by meeting it with death” (p. 202). The two opposing forces meld into one in the confusion as Eilish encounters “one checkpoint after another” with “different faces speaking the same commands” (p. 283). Her escape from the mystical terror across the border into the unknown dark countryside to the sea could have come directly from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s (1749–1832) The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774). Goethe wrote: “From the forbidding mountain range across the barren plain untrodden by the foot of man, to the end of the unknown seas, the spirit of the Eternal Creator can be felt rejoicing over every grain of dust”, emphasising the fearful, the mysterious and the unsure.

We live in stark, dark times, surrounded by media that is saturated with the Romanticist gloop of horror, terror, fantasy, science fiction, romantic egoism, etc., that threatens to slow society down and trap us into infinite and endless imagination to the detriment of any progressive forms of social consciousness and societal change.

Yet in the language of the Prophet Song there are many connotations of Ireland’s centuries long struggle against British Imperialism and colonialism: Ireland’s War of Independence, the war against the might of the British Empire in the description of the military men on horses (p.190), state forces moving in on college green (the scene of rebellions going back to the 19th century) (p. 94), cycling before the curfew, crossing the border (p. 112), the harp emblem (p. 123), a stage set up at the old parliament (now the Bank of Ireland HQ) against emergency powers and calling “for all political prisoners to be released” (p. 87). However, Prophet Song is not about a popular rising continuing on from Ireland’s tradition of radical opposition to authoritarian state forces.

The Apocalypse tradition: Karl Bryullov, The Last Day of Pompeii, 1833, The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

The Apocalypse tradition: Karl Bryullov, The Last Day of Pompeii, 1833, The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

It is in the Romanticist tradition of a powerful figure (the Prophet) who cries for the lack of love and compassion in the world and, in the apocalyptic tradition, calls for people to change their ways to avoid the wrath of God and the end of the world. The secular version, the postmodernist ‘End of History’ thesis leaves no hope for those who do not benefit from neoliberalism. The Romanticist escape to Utopia, the remote, the exotic, and the unknown, is in stark contrast with the real lives of past leaders and activists of collectivist and communitarian movements who suffered, struggled, and died for real social change.

No comments:

Post a Comment