JAMES PETRAS •

MAY 10, 2019

“Venezuela has the largest oil reserves in the world and they own it and we want it”

(Anonymous Trump official)

Introduction

US hostility and efforts to overthrow the Venezuelan government forms parts of a long and inglorious history of US intervention in Latin America going back to the second decade of the 19th century.

In 1823 US President Monroe declared, in his name, the ‘Monroe Doctrine” – the US right to keep Europeans out of the region, but the right of the US to intervene in pursuit of its economic, political and military interests.

We will proceed to outline the historical phases of US political and military intervention on behalf of US corporate and banking interests in the region and the Latin American political and social movements which opposed it.

The first period runs from the late 19th century to the 1930’s, and includes Marine invasions , the installation of US client dictatorships and the resistance of popular revolutions led by several revolutionary leaders in El Salvador, (Farabundo Marti), Nicaragua, (Augusto Sandino), Cuba (Jose Marti) and Mexico [Lazaro Cárdenas].

We will then discuss the Post-WWII US interventions , the overthrow of popular governments and the repression of social movements, including Guatemala (1954), Chile coup (1973), US invasion of the Dominican Republic (1965), Grenada (1982),and Panama (1989).

We will then exam US efforts to overthrow the Venezuela government (1998 to the present).

US Policy to Latin America: Democracy, Dictatorship and Social Movements

US General Smedley Butler summarized his 33 years in the military as a ‘muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers . . . I helped Mexico safe for American oil interest in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for National City Bank, to collect revenue . . . I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street. I helped purify Nicaragua for the . . . House of Brown Brothers in 1902 – 1912. I brought a light to the Dominican Republic for the American sugar interest in 2016. I helped make Honduras right for American fruit companies in 1903 . . . looking back on it, I could have given Al Capone a few hints’!

During the first 40 years of the 20th century the US invaded Cuba, converted it into a quasi-colony and repudiated its hero of independence Jose Marti; it provided advisers and military support to El Salvador’s dictator, assassinated its revolutionary leader Farabundo Marti and murdered 30,000 landless peasants seeking land reform. The US intervened in Nicaragua, fought against its patriotic leader Augusto Sandino and installed a dictatorial dynasty led by the Somoza regime until it was overthrown in 1979. The US intervened in Cuba to install a military dictatorship in 1933 to suppress an uprising of sugar workers .Between 1952 – 1958 Washington armed the Batista dictatorship to destroy the revolutionary July 26 Movement led by Fidel Castro. In the late 1930s the US threatened to invade Mexico when President Lazaro Cardenas nationalized the US oil companies and redistributed land to millions of landless peasants.

With the defeat of fascism (1941-45), there was an upsurge of social democratic governments in Latin America.But the US objected. In 1954 the US overthrew the elected Guatemala president Jacobo Arbenz for expropriating the banana plantations of United Fruit Company. It backed a military coup in Brazil in 1964, the military remained in power for 20 years. In 1963 the US overthrew the Dominican Republic’s democratically elected government of Juan Bosch and invaded in 1965 to prevent a popular uprising . In 1973 the US supported a military coup overthrowing democratic socialist president Salvador Allende and backed the military regime of General Augusto Pinochet for nearly 20 years. Subsequently, the US intervened and occupied Grenada in 1983 and Panama in 1989.

US propped up rightwing regimes throughout the region which backed US banking and corporate oligarchs which exploited resources, workers and peasants.

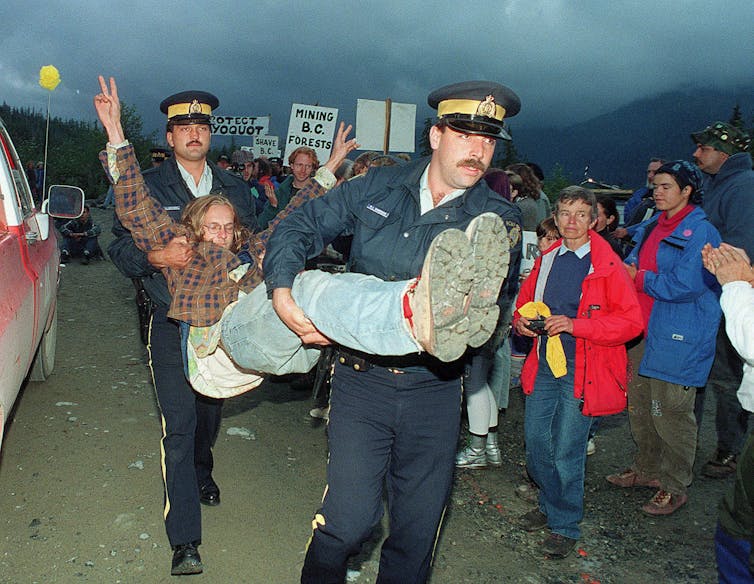

But by the early 1990’s powerful social movements led by workers, peasants, middle class public employees/doctors and teachers challenged the alliance of domestic and US elite rulers. In Brazil the 300,000 strong rural workers movement (MST) succeeded in expropriating large fallow estates; in Bolivia indigenous miners and peasants including coca farmers overthrew the oligarchy. In Argentina general strikes and mass movements of unemployed workers overthrew corrupt rulers allied with City Bank. The success of the popular nationalist and populist movements led to democratic elections won by progressive and leftist Presidents throughout Latin America, especially Venezuela.

Venezuela: Democratic Election, Social Reforms and the Election of President Chavez

In 1989 the US backed President of Venezuela imposed austerity programs that provoked popular demonstrations which led to the government ordering the police and military to repress the demonstrators: several thousand were killed and wounded. Hugo Chavez, a military official, rebelled and supported the populer uprising.He was captured, arrested, later freed and ran for presidential office.. He was elected by a wide margin in 1999 on a program of social reforms, economic nationalism, an end of corruption and political independence.

Washington began a hostile campaign to pressure President Chavez to accept Washington’s (President Bush) global war agenda in Afghanistan and around the world. Chavez refused to submit. He declared, “You don’t fight terror with terror”. By late 2001 the US Ambassador met with the business elite and a sector of the military to oust President elect Chavez via a coup in April 2002. The coup lasted 24 hours ..Over a million people, mostly slum dwellers, marched to the Presidential palace, backed by military loyalists .They defeated the coup and restored President Chavez to power. He proceeded to win a dozen democratic elections and referendums over the following decade. President Chavez succeeded in large part because of his comprehensive program of socio-economic reforms favoring the workers, unemployed and middle class.

Over 2 million houses and apartments were built and distributed free to the popular classes; hundreds of clinics and hospitals provided free health care in the populous neighborhoods; universities, training schools and medical centers for low income students were built with free tuition.

Thousands in neighborhood community centers and ‘local collectives’ discussed and voted on social and political issues – including criticism and recall of local politicians, even elected Chavez’ officials.

Between 1998 and 2012, President Chavez won four straight Presidential elections,several congressional majorities and two national referendums, garnering between 56% and over 60% of the popular vote.After Chavez died President Maduro won elections in 2013 and 2018 but by a narrower margin. Democracy flourished, elections were free and open to all parties.

As a result of the inability of US backed candidates to win elections, Washington resorted to violent street riots,and appealed to the military to revolt and reverse the electoral results. The US applied sanctions beginning with President Obama and deepen with President Trump. The US seized billions of dollars in Venezuelan assets, and oil refineries in the US. The US selected a (non-elected) new President (Guaido) who was directed to subvert the military to revolt and seize power.

They failed: about one hundred soldiers out of 267,000 and a few thousand rightwing supporters heeded the call. The “opposition” revolt was a failure.

US failures were predictable as the mass of voter defended their socio-economic gains; their control of local power; their dignity and respect. Over 80% of the population including the majority of the opposition – rejected a US invasion.

US sanctions contributed to hyper-inflation and the death of 40,000 Venezuelan citizens due to the scarcity of medical products.

Conclusion

The US and the CIA followed in the footsteps of the past century seeking to overthrow the Venezuelan government and seize control of its oil and mineral resources. As in the past the US sought to impose a submissive dictatorship which would repress the popular movements and subvert the democratic electoral processes. Washington sought to impose a electoral apparatus which would ensure the election of submissive rulers as it did in the past and as it has done in recent times in Paraguay, Brazil and Honduras.

So far Washington has failed, in great part because of the peoples’ defense of their historical gains. Most poor and working people are aware that a US invasion and occupation will lead to mass killing and the destruction of sovereignty and dignity.

The people are aware of US aggression as well as the mistakes of the government.They are demanding corrections and rectifications .The government of President Maduro favors a dialogue with the non-violent opposition; Venezuelans are developing economic ties with Russia, China, Iran, Turkey, Bolivia, Mexico and other independent countries.

Latin America has experienced decades of US exploitation and domination; but it has also created a history of successful popular resistance including revolutions in Mexico, Bolivia and Cuba; successful social movements and voting outcomes in recent years in Brazil, Argentina, Ecuador and Venezuela.

President Trump and his murderous cohort of Pompeo, Bolton and Abrams have declared war against the Venezuelan people but they have thus far been defeated.

The struggle continues.

“Venezuela has the largest oil reserves in the world and they own it and we want it”

(Anonymous Trump official)

Introduction

US hostility and efforts to overthrow the Venezuelan government forms parts of a long and inglorious history of US intervention in Latin America going back to the second decade of the 19th century.

In 1823 US President Monroe declared, in his name, the ‘Monroe Doctrine” – the US right to keep Europeans out of the region, but the right of the US to intervene in pursuit of its economic, political and military interests.

We will proceed to outline the historical phases of US political and military intervention on behalf of US corporate and banking interests in the region and the Latin American political and social movements which opposed it.

The first period runs from the late 19th century to the 1930’s, and includes Marine invasions , the installation of US client dictatorships and the resistance of popular revolutions led by several revolutionary leaders in El Salvador, (Farabundo Marti), Nicaragua, (Augusto Sandino), Cuba (Jose Marti) and Mexico [Lazaro Cárdenas].

We will then discuss the Post-WWII US interventions , the overthrow of popular governments and the repression of social movements, including Guatemala (1954), Chile coup (1973), US invasion of the Dominican Republic (1965), Grenada (1982),and Panama (1989).

We will then exam US efforts to overthrow the Venezuela government (1998 to the present).

US Policy to Latin America: Democracy, Dictatorship and Social Movements

US General Smedley Butler summarized his 33 years in the military as a ‘muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers . . . I helped Mexico safe for American oil interest in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for National City Bank, to collect revenue . . . I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street. I helped purify Nicaragua for the . . . House of Brown Brothers in 1902 – 1912. I brought a light to the Dominican Republic for the American sugar interest in 2016. I helped make Honduras right for American fruit companies in 1903 . . . looking back on it, I could have given Al Capone a few hints’!

During the first 40 years of the 20th century the US invaded Cuba, converted it into a quasi-colony and repudiated its hero of independence Jose Marti; it provided advisers and military support to El Salvador’s dictator, assassinated its revolutionary leader Farabundo Marti and murdered 30,000 landless peasants seeking land reform. The US intervened in Nicaragua, fought against its patriotic leader Augusto Sandino and installed a dictatorial dynasty led by the Somoza regime until it was overthrown in 1979. The US intervened in Cuba to install a military dictatorship in 1933 to suppress an uprising of sugar workers .Between 1952 – 1958 Washington armed the Batista dictatorship to destroy the revolutionary July 26 Movement led by Fidel Castro. In the late 1930s the US threatened to invade Mexico when President Lazaro Cardenas nationalized the US oil companies and redistributed land to millions of landless peasants.

With the defeat of fascism (1941-45), there was an upsurge of social democratic governments in Latin America.But the US objected. In 1954 the US overthrew the elected Guatemala president Jacobo Arbenz for expropriating the banana plantations of United Fruit Company. It backed a military coup in Brazil in 1964, the military remained in power for 20 years. In 1963 the US overthrew the Dominican Republic’s democratically elected government of Juan Bosch and invaded in 1965 to prevent a popular uprising . In 1973 the US supported a military coup overthrowing democratic socialist president Salvador Allende and backed the military regime of General Augusto Pinochet for nearly 20 years. Subsequently, the US intervened and occupied Grenada in 1983 and Panama in 1989.

US propped up rightwing regimes throughout the region which backed US banking and corporate oligarchs which exploited resources, workers and peasants.

But by the early 1990’s powerful social movements led by workers, peasants, middle class public employees/doctors and teachers challenged the alliance of domestic and US elite rulers. In Brazil the 300,000 strong rural workers movement (MST) succeeded in expropriating large fallow estates; in Bolivia indigenous miners and peasants including coca farmers overthrew the oligarchy. In Argentina general strikes and mass movements of unemployed workers overthrew corrupt rulers allied with City Bank. The success of the popular nationalist and populist movements led to democratic elections won by progressive and leftist Presidents throughout Latin America, especially Venezuela.

Venezuela: Democratic Election, Social Reforms and the Election of President Chavez

In 1989 the US backed President of Venezuela imposed austerity programs that provoked popular demonstrations which led to the government ordering the police and military to repress the demonstrators: several thousand were killed and wounded. Hugo Chavez, a military official, rebelled and supported the populer uprising.He was captured, arrested, later freed and ran for presidential office.. He was elected by a wide margin in 1999 on a program of social reforms, economic nationalism, an end of corruption and political independence.

Washington began a hostile campaign to pressure President Chavez to accept Washington’s (President Bush) global war agenda in Afghanistan and around the world. Chavez refused to submit. He declared, “You don’t fight terror with terror”. By late 2001 the US Ambassador met with the business elite and a sector of the military to oust President elect Chavez via a coup in April 2002. The coup lasted 24 hours ..Over a million people, mostly slum dwellers, marched to the Presidential palace, backed by military loyalists .They defeated the coup and restored President Chavez to power. He proceeded to win a dozen democratic elections and referendums over the following decade. President Chavez succeeded in large part because of his comprehensive program of socio-economic reforms favoring the workers, unemployed and middle class.

Over 2 million houses and apartments were built and distributed free to the popular classes; hundreds of clinics and hospitals provided free health care in the populous neighborhoods; universities, training schools and medical centers for low income students were built with free tuition.

Thousands in neighborhood community centers and ‘local collectives’ discussed and voted on social and political issues – including criticism and recall of local politicians, even elected Chavez’ officials.

Between 1998 and 2012, President Chavez won four straight Presidential elections,several congressional majorities and two national referendums, garnering between 56% and over 60% of the popular vote.After Chavez died President Maduro won elections in 2013 and 2018 but by a narrower margin. Democracy flourished, elections were free and open to all parties.

As a result of the inability of US backed candidates to win elections, Washington resorted to violent street riots,and appealed to the military to revolt and reverse the electoral results. The US applied sanctions beginning with President Obama and deepen with President Trump. The US seized billions of dollars in Venezuelan assets, and oil refineries in the US. The US selected a (non-elected) new President (Guaido) who was directed to subvert the military to revolt and seize power.

They failed: about one hundred soldiers out of 267,000 and a few thousand rightwing supporters heeded the call. The “opposition” revolt was a failure.

US failures were predictable as the mass of voter defended their socio-economic gains; their control of local power; their dignity and respect. Over 80% of the population including the majority of the opposition – rejected a US invasion.

US sanctions contributed to hyper-inflation and the death of 40,000 Venezuelan citizens due to the scarcity of medical products.

Conclusion

The US and the CIA followed in the footsteps of the past century seeking to overthrow the Venezuelan government and seize control of its oil and mineral resources. As in the past the US sought to impose a submissive dictatorship which would repress the popular movements and subvert the democratic electoral processes. Washington sought to impose a electoral apparatus which would ensure the election of submissive rulers as it did in the past and as it has done in recent times in Paraguay, Brazil and Honduras.

So far Washington has failed, in great part because of the peoples’ defense of their historical gains. Most poor and working people are aware that a US invasion and occupation will lead to mass killing and the destruction of sovereignty and dignity.

The people are aware of US aggression as well as the mistakes of the government.They are demanding corrections and rectifications .The government of President Maduro favors a dialogue with the non-violent opposition; Venezuelans are developing economic ties with Russia, China, Iran, Turkey, Bolivia, Mexico and other independent countries.

Latin America has experienced decades of US exploitation and domination; but it has also created a history of successful popular resistance including revolutions in Mexico, Bolivia and Cuba; successful social movements and voting outcomes in recent years in Brazil, Argentina, Ecuador and Venezuela.

President Trump and his murderous cohort of Pompeo, Bolton and Abrams have declared war against the Venezuelan people but they have thus far been defeated.

The struggle continues.