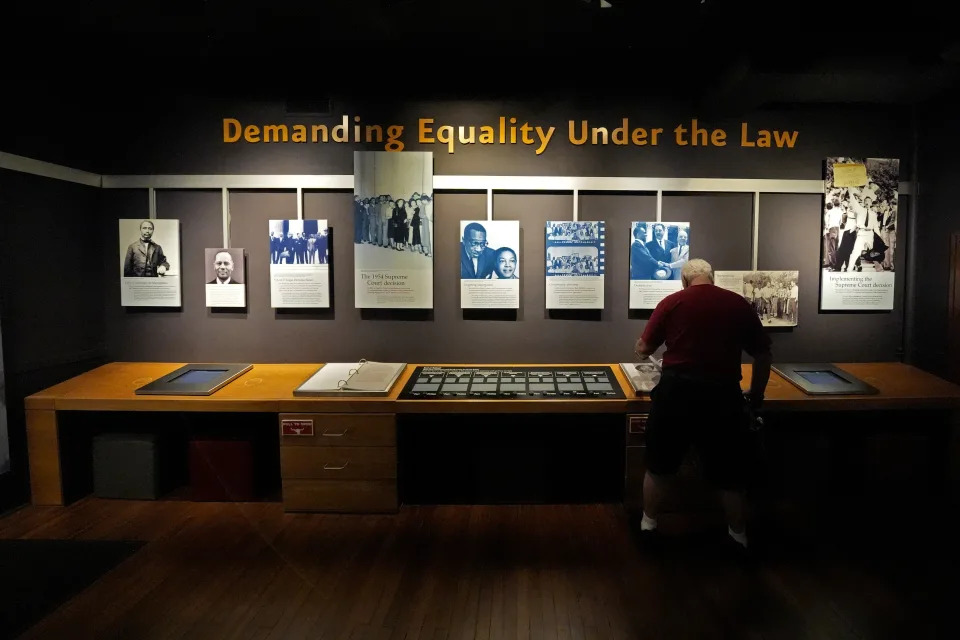

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court laid out a new precedent: Separate but equal has no place in American schools.

Chandelis Duster, Nicquel Terry Ellis and Alex Leeds Matthews

CNN

Thu, May 16, 2024

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas – the landmark Supreme Court decision that declared “separate but equal” education unconstitutional in the United States – remains one of the most consequential court cases in American history.

As the nation commemorates the ruling’s 70th anniversary, civil rights leaders and advocates tell CNN the case may have paved the way for more equal and integrated schools, but fierce – and continued – opposition to integration means the ruling in no way assured the end of segregated education in the United States.

Although progress has undoubtedly been made over the decades, research shows many school districts today are racially segregated because they are divided along residential and economic lines. At times, federal courts have intervened, ordering some school districts to execute plans to integrate Black and Latino students with their White counterparts to improve educational opportunities.

Gary Orfield, a professor at UCLA and co-director of the university’s Civil Rights Project, said although there’s been a steady increase in enrollment of non-White students in public schools, his research shows more students attend schools that are “intensely segregated” now than they did 30 years ago.

That’s when the Supreme Court ruled in Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell that court-ordered desegregation plans were “not intended to operate in perpetuity,” allowing more segregation to take place over time as school districts reverted to neighborhood zoning.

De facto segregation persists today, Orfield said, because many states have abandoned efforts to enforce integration.

“There are many places where courts ended desegregation orders that had been accepted. A great many of the magnet schools that had been integrated for decades under court orders were resegregated,” he said. “These were such tragic changes, throwing away real successes in a very polarized country.”

A ‘massive resistance’ to integration

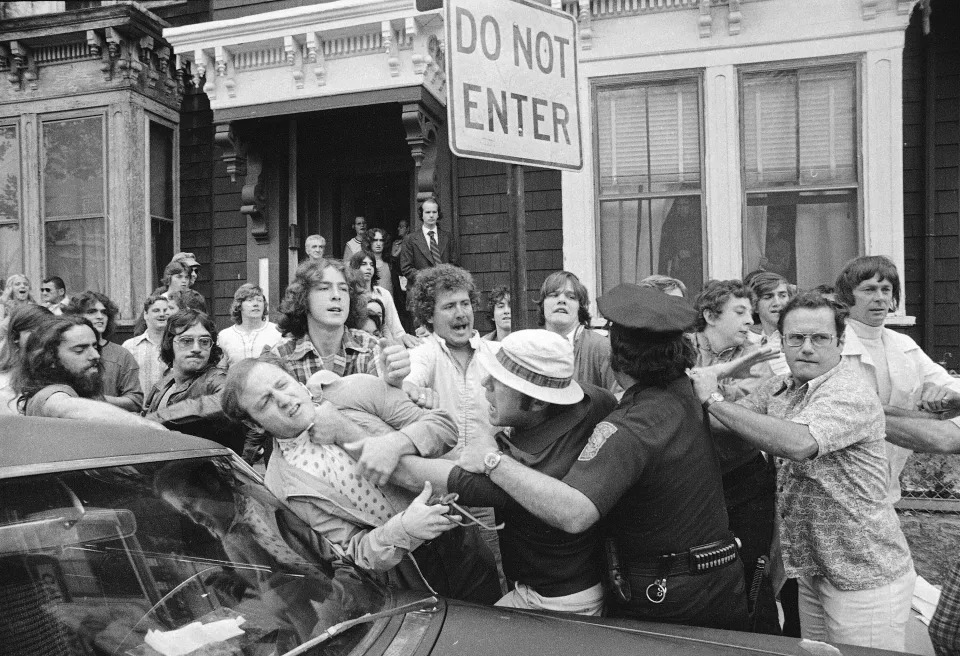

Historically, efforts to desegregate schools were at times met with violent resistance from White Americans.

In response to the Brown decision, 101 southern lawmakers – roughly a fifth of Congress – signed what would become known as the “Southern Manifesto,” which encouraged states to “resist forced integration by any lawful means.”

Hazel Bryan, center left, and other students of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, shout insults at Elizabeth Eckford as she calmly walks to a line of National Guardsmen who blocked the main entrance and would not let her enter on September 4, 1957. - Will Counts/Arkansas Democrat Gazette via AP

“If we can organize the Southern States for massive resistance to this order, I think that in time the rest of the country will realize that racial integration is not going to be accepted in the South,” Virginia Sen. Harry Flood Byrd said in the days after the ruling was announced.

That “massive resistance” campaign spread throughout southern states.

In 1957, three years after the Brown ruling, all eyes turned to Little Rock Central High in Arkansas as nine Black students were escorted into the school by soldiers in the US Army’s 101st Airborne Division. The students are known today as the Little Rock Nine.

Then, in 1965, a legal battle over integration in Mississippi began that would last more than 50 years.

That year, Dianna Cowan White’s parents listed her as the plaintiff in a lawsuit against the Bolivar County Board of Education, now the Cleveland School District, in Cleveland, Mississippi, because the district still forced Black students to attend an all-Black school.

The district fought the lawsuit for more than five decades and in 2016, it would become one of the last in the country to officially desegregate, CNN previously reported.

That ruling, advocates say, signaled that the fight to integrate schools was far from over.

According to Orfield’s research, which examines school integration across the country, desegregation efforts peaked in the 1980s and there’s since been a decline in the percentage of Black students attending majority-White schools.

Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall – who argued the original Brown v. Board of Education case as a lawyer – wrote the dissenting opinion in Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell, the 1991 Supreme Court decision that released school districts from desegregation orders.

“The majority today suggests that 13 years of desegregation was enough,” Marshall wrote, adding that in his view, an order to lift any desegregation decree “must take into account the unique harm” associated with racially segregated schools and “must expressly demand the elimination of such schools.”

But even in schools that are integrated, racist bullying and discrimination persists. From 2018 to 2022, more than 4,300 hate crimes were reported in schools, with the largest number of alleged offenses being motivated by anti-Black bias, according to a report from the Department of Justice released in January.

‘Vestiges of segregation’

As of 2020, more than 700 school districts and charter schools were under a legal desegregation order or voluntary agreement to desegregate, according to the Century Foundation, an independent think tank that works toward equity in education, among other goals.

Leslie Fenwick, dean emeritus and professor at the Howard University School of Education, told CNN the decades of opposition to integration efforts has also led to a decrease in the number of Black educators. She explores the unintended consequences to the Brown decision in her book, “Jim Crow’s Pink Slip: The Untold Story of Black Principal and Teacher Leadership.”

“We never define segregation the right way. In everybody’s mind still, when we say segregation, we’re only focused on students,” she told CNN. “The great failing, not of the decision, but of massive resistance to the decision, was that we wiped out 100,000 Black principals and teachers who were fired, dismissed and demoted.”

The original Brown v. Board of Education case was also litigated by lawyers with the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund, the nation’s first civil rights law firm, which Marshall founded in 1940.

Since the Brown ruling, the civil rights legal group says it has “sued hundreds of school districts across the country to vindicate the promise of Brown.”

Today, there are more than 200 open school desegregation cases currently on the federal dockets, according to the LDF, which estimates its lawyers are handling about a hundred of those cases.

Michaele Turnage Young, senior counsel and co-manager of the Equal Protection Initiative at the LDF, said these lawsuits are necessary because the “vestiges of school segregation” still exist today.

Young said many majority-White schools are often better equipped with educational resources and better trained staff than majority-Black schools in the same school district. She noted other disparities include a lack of screenings for gifted programs, college prep programs and extracurricular activity offerings, and lower graduation rates.

The anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education comes nearly a year after the Supreme Court gutted affirmative action in higher education, which sparked a conservative-led movement to outlaw diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) programs at public colleges and universities.

Some critics of DEI say the programs are discriminatory against White Americans. But civil rights advocates and legal scholars tell CNN that arguments to end affirmative action and curb DEI are often premised on the idea that America has already achieved racial equality in education – a notion they say is far from the truth.

Demonstrators for and against the U.S. Supreme Court decision to strike down race-conscious student admissions programs at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina confront each other. - Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters/File

NAACP President and CEO Derrick Johnson said he hasn’t been surprised by the culture war that’s now playing out in school districts across the country because “history has taught us that progress is not made in a straight line.”

“We will continue to see these reactions until more citizens realize that equal protection under the law, our ability to grow and prosper as a nation, will be based on our diversity and not on a single culture or racial identity,” Johnson said.

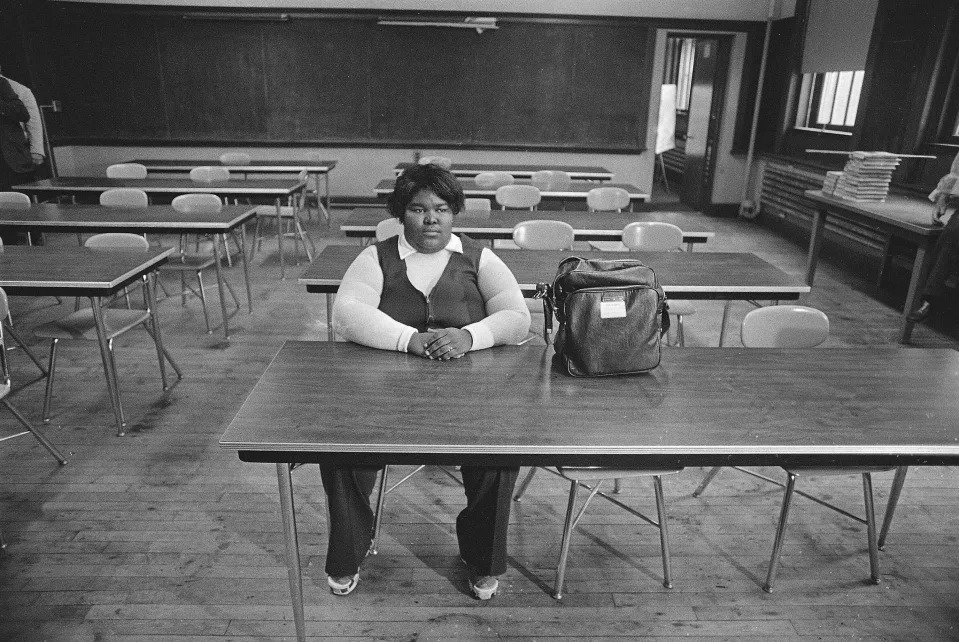

Dianna Cowan White told CNN her parents were able to enroll her in an all-White school while their legal case against the Bolivar School District wound through the courts.

More than 50 years later, she says she can still recall how her 6th grade classmates taunted her, often saying “go back to where you came from” or, “did you paint your skin black?”

“They did not want me there,” White told CNN. “I felt like I was alone.”

But she also recalled the all-White school had better quality books, and was teaching a curriculum that was far more advanced than the Black school she had previously attended in the same district.

The experience ultimately influenced her decision to send her children to racially diverse schools, despite the racism she encountered, because she felt they would have better opportunities.

White said when she learned of the judge’s ruling to desegregate the school district in 2016 her first reaction was, “it was about time.”

“We are in the 21st century, when do you let it go?”

Topeka was at the center of Brown v. Board. Decades later, segregation of another sort lingers

Thu, May 16, 2024

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas – the landmark Supreme Court decision that declared “separate but equal” education unconstitutional in the United States – remains one of the most consequential court cases in American history.

As the nation commemorates the ruling’s 70th anniversary, civil rights leaders and advocates tell CNN the case may have paved the way for more equal and integrated schools, but fierce – and continued – opposition to integration means the ruling in no way assured the end of segregated education in the United States.

Although progress has undoubtedly been made over the decades, research shows many school districts today are racially segregated because they are divided along residential and economic lines. At times, federal courts have intervened, ordering some school districts to execute plans to integrate Black and Latino students with their White counterparts to improve educational opportunities.

Gary Orfield, a professor at UCLA and co-director of the university’s Civil Rights Project, said although there’s been a steady increase in enrollment of non-White students in public schools, his research shows more students attend schools that are “intensely segregated” now than they did 30 years ago.

That’s when the Supreme Court ruled in Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell that court-ordered desegregation plans were “not intended to operate in perpetuity,” allowing more segregation to take place over time as school districts reverted to neighborhood zoning.

De facto segregation persists today, Orfield said, because many states have abandoned efforts to enforce integration.

“There are many places where courts ended desegregation orders that had been accepted. A great many of the magnet schools that had been integrated for decades under court orders were resegregated,” he said. “These were such tragic changes, throwing away real successes in a very polarized country.”

A ‘massive resistance’ to integration

Historically, efforts to desegregate schools were at times met with violent resistance from White Americans.

In response to the Brown decision, 101 southern lawmakers – roughly a fifth of Congress – signed what would become known as the “Southern Manifesto,” which encouraged states to “resist forced integration by any lawful means.”

Hazel Bryan, center left, and other students of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, shout insults at Elizabeth Eckford as she calmly walks to a line of National Guardsmen who blocked the main entrance and would not let her enter on September 4, 1957. - Will Counts/Arkansas Democrat Gazette via AP

“If we can organize the Southern States for massive resistance to this order, I think that in time the rest of the country will realize that racial integration is not going to be accepted in the South,” Virginia Sen. Harry Flood Byrd said in the days after the ruling was announced.

That “massive resistance” campaign spread throughout southern states.

In 1957, three years after the Brown ruling, all eyes turned to Little Rock Central High in Arkansas as nine Black students were escorted into the school by soldiers in the US Army’s 101st Airborne Division. The students are known today as the Little Rock Nine.

Then, in 1965, a legal battle over integration in Mississippi began that would last more than 50 years.

That year, Dianna Cowan White’s parents listed her as the plaintiff in a lawsuit against the Bolivar County Board of Education, now the Cleveland School District, in Cleveland, Mississippi, because the district still forced Black students to attend an all-Black school.

The district fought the lawsuit for more than five decades and in 2016, it would become one of the last in the country to officially desegregate, CNN previously reported.

That ruling, advocates say, signaled that the fight to integrate schools was far from over.

According to Orfield’s research, which examines school integration across the country, desegregation efforts peaked in the 1980s and there’s since been a decline in the percentage of Black students attending majority-White schools.

Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall – who argued the original Brown v. Board of Education case as a lawyer – wrote the dissenting opinion in Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell, the 1991 Supreme Court decision that released school districts from desegregation orders.

“The majority today suggests that 13 years of desegregation was enough,” Marshall wrote, adding that in his view, an order to lift any desegregation decree “must take into account the unique harm” associated with racially segregated schools and “must expressly demand the elimination of such schools.”

But even in schools that are integrated, racist bullying and discrimination persists. From 2018 to 2022, more than 4,300 hate crimes were reported in schools, with the largest number of alleged offenses being motivated by anti-Black bias, according to a report from the Department of Justice released in January.

‘Vestiges of segregation’

As of 2020, more than 700 school districts and charter schools were under a legal desegregation order or voluntary agreement to desegregate, according to the Century Foundation, an independent think tank that works toward equity in education, among other goals.

Leslie Fenwick, dean emeritus and professor at the Howard University School of Education, told CNN the decades of opposition to integration efforts has also led to a decrease in the number of Black educators. She explores the unintended consequences to the Brown decision in her book, “Jim Crow’s Pink Slip: The Untold Story of Black Principal and Teacher Leadership.”

“We never define segregation the right way. In everybody’s mind still, when we say segregation, we’re only focused on students,” she told CNN. “The great failing, not of the decision, but of massive resistance to the decision, was that we wiped out 100,000 Black principals and teachers who were fired, dismissed and demoted.”

The original Brown v. Board of Education case was also litigated by lawyers with the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund, the nation’s first civil rights law firm, which Marshall founded in 1940.

Since the Brown ruling, the civil rights legal group says it has “sued hundreds of school districts across the country to vindicate the promise of Brown.”

Today, there are more than 200 open school desegregation cases currently on the federal dockets, according to the LDF, which estimates its lawyers are handling about a hundred of those cases.

Michaele Turnage Young, senior counsel and co-manager of the Equal Protection Initiative at the LDF, said these lawsuits are necessary because the “vestiges of school segregation” still exist today.

Young said many majority-White schools are often better equipped with educational resources and better trained staff than majority-Black schools in the same school district. She noted other disparities include a lack of screenings for gifted programs, college prep programs and extracurricular activity offerings, and lower graduation rates.

The anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education comes nearly a year after the Supreme Court gutted affirmative action in higher education, which sparked a conservative-led movement to outlaw diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) programs at public colleges and universities.

Some critics of DEI say the programs are discriminatory against White Americans. But civil rights advocates and legal scholars tell CNN that arguments to end affirmative action and curb DEI are often premised on the idea that America has already achieved racial equality in education – a notion they say is far from the truth.

Demonstrators for and against the U.S. Supreme Court decision to strike down race-conscious student admissions programs at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina confront each other. - Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters/File

NAACP President and CEO Derrick Johnson said he hasn’t been surprised by the culture war that’s now playing out in school districts across the country because “history has taught us that progress is not made in a straight line.”

“We will continue to see these reactions until more citizens realize that equal protection under the law, our ability to grow and prosper as a nation, will be based on our diversity and not on a single culture or racial identity,” Johnson said.

Dianna Cowan White told CNN her parents were able to enroll her in an all-White school while their legal case against the Bolivar School District wound through the courts.

More than 50 years later, she says she can still recall how her 6th grade classmates taunted her, often saying “go back to where you came from” or, “did you paint your skin black?”

“They did not want me there,” White told CNN. “I felt like I was alone.”

But she also recalled the all-White school had better quality books, and was teaching a curriculum that was far more advanced than the Black school she had previously attended in the same district.

The experience ultimately influenced her decision to send her children to racially diverse schools, despite the racism she encountered, because she felt they would have better opportunities.

White said when she learned of the judge’s ruling to desegregate the school district in 2016 her first reaction was, “it was about time.”

“We are in the 21st century, when do you let it go?”

Topeka was at the center of Brown v. Board. Decades later, segregation of another sort lingers

HEATHER HOLLINGSWORTH

Wed, May 15, 2024 at 10:11 p.m. MDT·5 min read

Fifth grader Malaya Webster, right, plays a game with other students at Williams Science and Arts Magnet school Friday, May 10, 2024, in Topeka, Kan. The school is just a block from the former Monroe school which was at the center of the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling ending segregation in public schools 70 years ago. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

TOPEKA, Kan. (AP) — The lesson on diversity started slowly in a first-grade classroom in Topeka, where schools were at the center of a case that struck down segregated education.

“I like broccoli. Do you like broccoli?” Marie Carter, a Black school library worker, asked broccoli-hating librarian Amy Gugelman, who is white.

The students were comparing what makes them the same and what makes them different. It’s part of their introduction to Brown v. Board of Education, a ruling commemorated at a national historic site in a former all-Black school just down the street. Linda Brown, whose father Oliver Brown was the lead plaintiff in the case, was a student there.

Within a few questions, the first-graders at Williams Science & Fine Arts Magnet school watched the two women hold their arms next to each other. “My skin is brown,” Carter observed, “and Mrs. Gugelman’s skin is not.”

And then Gugelman reached the heart of the lesson. “Can we still be friends?”

The students, themselves a range of ethnicities, screamed out “yes!” oblivious to the messiness of the question, to the history of this place, to the struggles with race and equity that continue even now.

In school lessons, memorials and ceremonies, Topeka is marking its ties to the 1954 ruling that struck down “separate but equal.” But just as clear to many is the legacy of discrimination that stands in the way of its promise of equity in Topeka and elsewhere.

The district is now 36% white, down from 72% in 1987. The changes coincide with the nation growing more diverse. Yet none of Topeka’s neighboring districts have a white enrollment below 64%; one district has a 94% white enrollment.

This concentration of students of color in districts with higher numbers of poor students partially reflects historic redlining and that poorer families couldn’t afford to move to suburban districts with more costly homes, said Frank Henderson, who has served on the state and national school board associations.

Four years ago, the largely white suburban district of Seaman, north of Topeka, where Henderson was the first Black school board member, was forced to confront the darker aspects of its past.

In 2020, student journalists confirmed the district’s namesake, Fred Seaman, was a regional leader of the Ku Klux Klan a century ago. The school board ultimately voted unanimously to renounce Seaman and his KKK activities but to keep the name.

“I felt it was probably the best that could be done to be able to address this hot issue,” said Henderson, whose 16 1/2-year school board term ended in January.

Madeline Gearhart, who was co-editor-in-chief of the high school newspaper, was disappointed. But now she thinks the student journalists who broke the story laid the groundwork for the issue to be taken up later in a district that is 80% white.

“I just think it’s so ironic that in a world where Topeka was a part of Brown v. Board, we still are maintaining the namesake of the district and not trying to disassociate,” said Gearhart, who is white and now a junior at the University of Kansas.

Seven years after the historic ruling, Beryl New began attending the all-Black school, Monroe Elementary, where Linda Brown and another plaintiff child were students. It was still largely segregated, not by district policy, but by redlining.

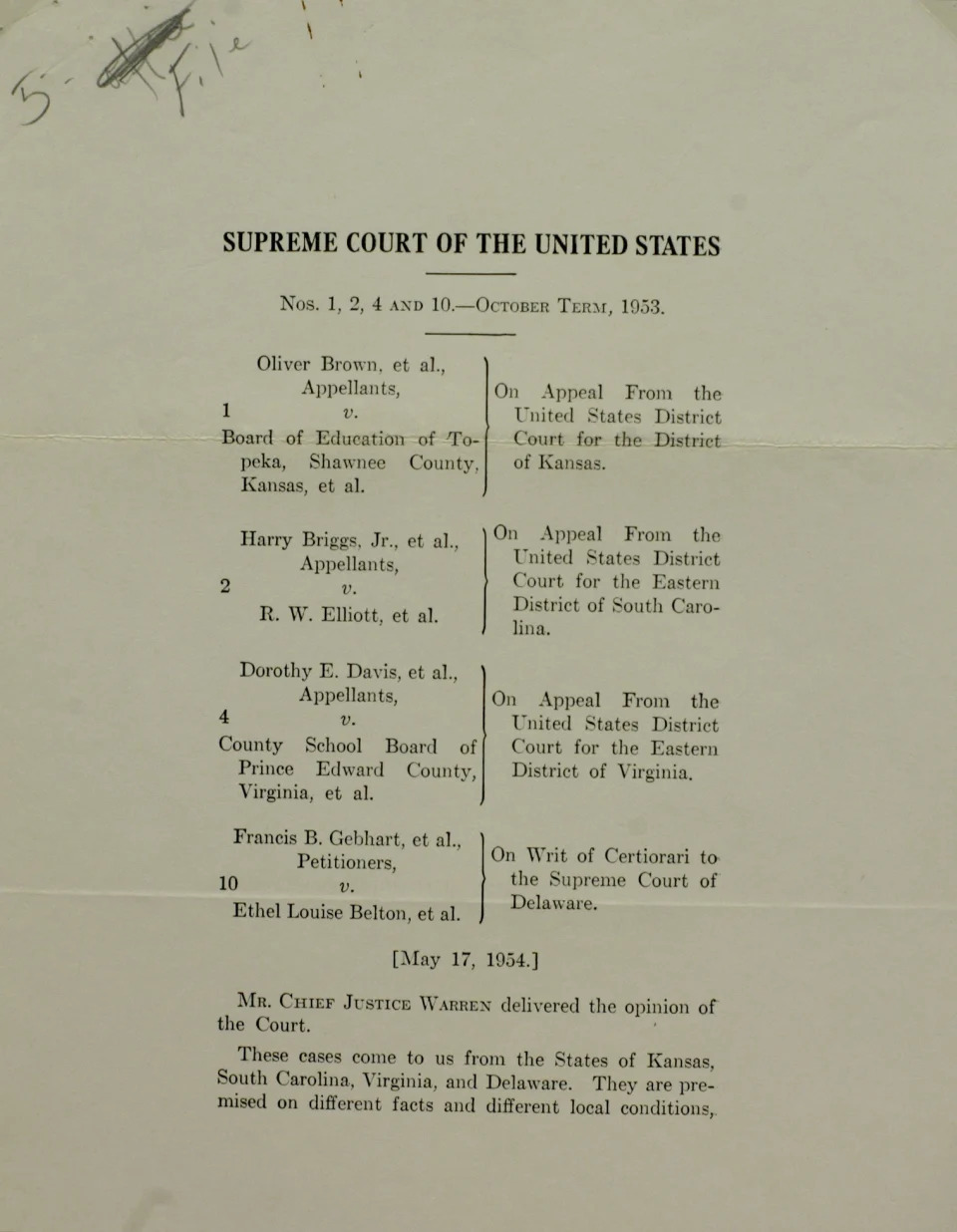

Her family was friends with the president of the Topeka chapter of the NAACP who recruited the 13 families that sued the Topeka district. Their case was eventually joined by school desegregation cases from Virginia, South Carolina and Delaware. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court overturned the doctrine of “separate but equal” in the case that bore Oliver Brown’s name. A similar case from Washington, D.C., was decided at the same time in a separate ruling.

The ruling embarrassed city leaders because they believed they had built equitable schools for white and Black students, said New, who serves on the African Affairs Commission for Kansas and is a former principal and district administrator.

“But of course, there were issues that were deeper than just what a building looks like,” she said.

For New, the mission now is to diversify the district’s workforce. Nationally, only about 45% of public school students are now white, but around 80% of teachers are, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

The district is handing out symbolic teaching contracts to high schoolers and vowing to hire them when they graduate from college. And to clear roadblocks for Black aides who want to become full-fledged teachers, it sometimes pays their salaries while they student teach.

That is what allowed teacher Jolene Tyree, who is Black, to finish her degree. The longtime-aide, hopes it makes a difference to her students to have someone who looks like them. Growing up, she recalls having very few Black teachers.

“You just feel somewhat on the outer side,” said Tyree, whose mother also attended Monroe and whose first-graders are now learning about the desegregation case.

Back in the library, Tyree’s students’ lesson was ending. Tiffany Anderson, Topeka’s first Black female superintendent, strode to the front of the room, quizzing the children on whether they wanted to be teachers, doctors or even the president of the United States someday.

Hands shot into the air. Anderson said many of the kids wouldn’t have done so in the past because they hadn’t seen anyone who looked like them in those roles.

“So, boys and girls,” Anderson said, “as I’m looking out at the sea of differences that make you all special, ... I just want to remind you, do differences really matter?”

The children shouted “no” before trickling out of the room.

Seven-year-old Jamari Lyons stayed behind.

“It’s OK to be white. And it’s OK to be Black. You can still be friends. You can still be neighbors. You can still love each other,” Jamari said, spreading his arms out wide.

Then he asked: “Right?”

___

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

70 years after Brown v. Board, America is both more diverse — and more segregated

SHARON LURYE

Thu, May 16, 2024

School backpacks hang on a rack at West Orange Elementary School in Orange, Calif., March 18, 2021. Seventy years after the Supreme Court's Brown v. Board, America is both more diverse — and more segregated.

(AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court laid out a new precedent: Separate but equal has no place in American schools.

The message of Brown v. Board of Education was clear. But 70 years later, the impact of the decision is still up for debate. Have Americans truly ended segregation in fact, not just in law?

The answer is complicated. U.S. schools in recent decades have grown far more diverse and, by some measures, more segregated, according to an Associated Press analysis.

On one hand, the number of Black and white students who go to school almost exclusively with students of the same race is at an all-time low.

On the other hand, huge shares of students of color still go to schools with almost no white students. Hispanic segregation is worse now than in the 1960s. The nation’s largest school districts, in particular, have seen a surge in segregation since the 1990s, according to research from Stanford University’s Educational Opportunity Project.

The history of school desegregation efforts, from Brown v. Board to today, shows how far the U.S. has come – and how far it has to go.

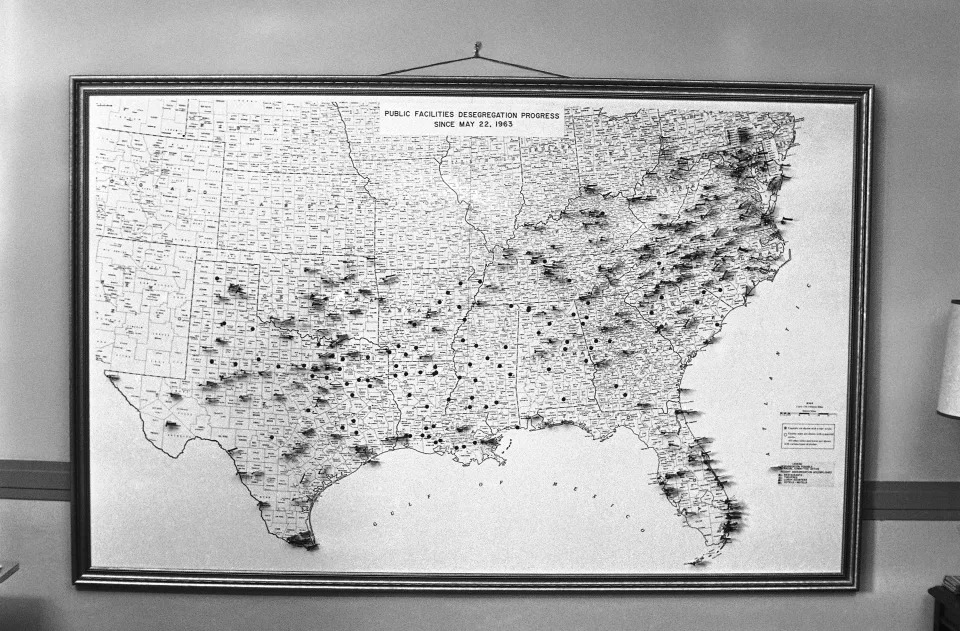

1954-1964: THE SOUTH DRAGS ITS FEET

The Brown v. Board decision declared white and Black students could not be forced to attend separate schools, even if those schools were allegedly equal in quality.

A few states such as Kansas and Delaware made some effort to comply with the order. But leaders in the Deep South immediately declared what U.S. Sen. Harry Byrd of Virginia called ” massive resistance ″ to integration.

In all, segregation levels changed little over the next decade, despite the bravery of Black students like the Little Rock Nine in 1957 and 6-year-old Ruby Bridges in New Orleans in 1960, who faced violent, racist mobs when they tried to desegregate their local schools.

1964-1986: DESEGREGATION GETS SERIOUS

By the mid-1960s, the federal courts lost patience with the South. They started to mete out desegregation orders with teeth, requiring busing if necessary. Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan Jr. declared segregation must be ripped out “root and branch.”

At the same time, civil rights legislation of the 1960s reshaped schools in far-reaching ways. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 banned discrimination in education; the Voting Rights Act gave Black voters more power to choose school boards; and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act offered schools federal cash if they desegregated. Meanwhile, the Immigration and Nationality Act opened the country to more immigrants from Asia, Africa and Latin America, leading to far more diverse schools.

From there, segregation decreased quickly. Almost every Black student in the South went to school only with people of color in 1963; only one-fourth of Black students did in 1968.

But desegregation came with a price: Thousands of qualified Black teachers were laid off, even though they were often more credentialed and qualified than white teachers.

“Integration has never been equitable,” said Ivory Toldson, a professor at Howard University.

Courts also began pushing desegregation in other parts of the country. Denver was one of the first cities outside the South called out for segregation in a 1973 Supreme Court case. Places like San Francisco and Cleveland were subject to desegregation orders, and riots broke out in 1974 over busing orders in Boston.

The momentum was short-lived. In 1974, the Supreme Court in Milliken v. Bradley struck down a desegregation plan that involved multiple school districts in and around Detroit. That meant metropolitan areas, with rare exceptions, could not be forced to bus students across school district lines.

The era saw massive white flight from urban school districts, in places where busing was required and where it was not. Los Angeles, Chicago and New York City collectively lost over half a million white public school students from 1968 to 1980. In just twelve years, the number of white students fell 71% in New Orleans, 78% in Detroit and 86% in Atlanta.

Still, federal court orders had succeeded in reducing Black segregation to its lowest level ever by 1986.

After that, progress began to stall.

1986-TODAY: DIVERSITY GROWS, DESEGREGATION LOSES STEAM

The courts gradually began to focus less on achieving racially balanced schools and more on other ways to promote desegregation, such as magnet schools. It became easier for school districts to argue they had made enough progress to be released from desegregation orders, and most of them were lifted by the early 2000s. A few hundred are still active today, but usually unenforced; school district leaders often don’t know they’re still under desegregation orders.

The segregation of Black students changed little after the 1980s. As Latino immigration soared, so did the segregation of Latino students.

The effects of isolation are particularly pernicious for students who come from an immigrant background, said Patricia Gándara, co-director of UCLA’s Civil Rights Project. These families are less likely to speak English or know the unspoken rules of the American education system, like how to apply for college.

More court cases chipped away at policy tools to address desegregation, turning toward the conservative idea that setting targets by race is itself a form of racial discrimination.

Nevertheless, classrooms became more diverse, reflecting the country’s changing demographics. A historic milestone came in 2014, when for the first time the majority of U.S. students were children of color.

Students of color may be more exposed to each other, but they’re still often in separate schools from white students. Around 4 out of 10 Black and Hispanic students go to schools made up almost entirely of other students of color.

Racial imbalance is particularly acute in the nation’s 100 largest districts, according to researchers from Stanford’s Educational Opportunity Project. Using segregation scores of 0 to 100, they found Black-white segregation grew over 40% from 1991 to 2019, from 21 to 30 points, while Hispanic-white segregation grew from 15 to 24.

That’s both because the government moved away from desegregation orders in the 1990s and because parents took advantage of the school choice movement in the 2000s.

Even before school choice, racial isolation was extreme in many large urban school districts. This is one of the reasons that many states with large cities outside the South, such as Illinois, Michigan, New York and California, have been among the most segregated in America since at least the 1980s.

This segregation matters, because concentration in high-poverty, racially segregated schools is strongly correlated with poorer outcomes for students.

“Segregation is at the core of an awful lot of the problems that we have,” Gándara said. “No matter how much money you throw at it, if you’re going to cluster poor kids and kids without family resources to support them in school, you’re going to continue to have these uneven outcomes.”

___

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Biden marks Brown v. Board of Education anniversary amid signs of erosion in Black voter support

AAMER MADHANI

Updated Thu, May 16, 2024

NAACP President Derrick Johnson, second from left, speaks to reporters outside the White House in Washington, Thursday, May 16, 2024, after meeting with President Joe Biden to mark the 50th anniversary of the historic Supreme Court decision. Johnson is joined by, from left, Brown v. Board of Education plaintiff and veteran John Stokes, Nathaniel Briggs, son of Brown v. Board of Education named plaintiff Harry Briggs Jr., and Cheryl Brown Henderson, daughter of Brown v. Board of Education named plaintiff Oliver Brown. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh)

ASSOCIATED PRESSMore

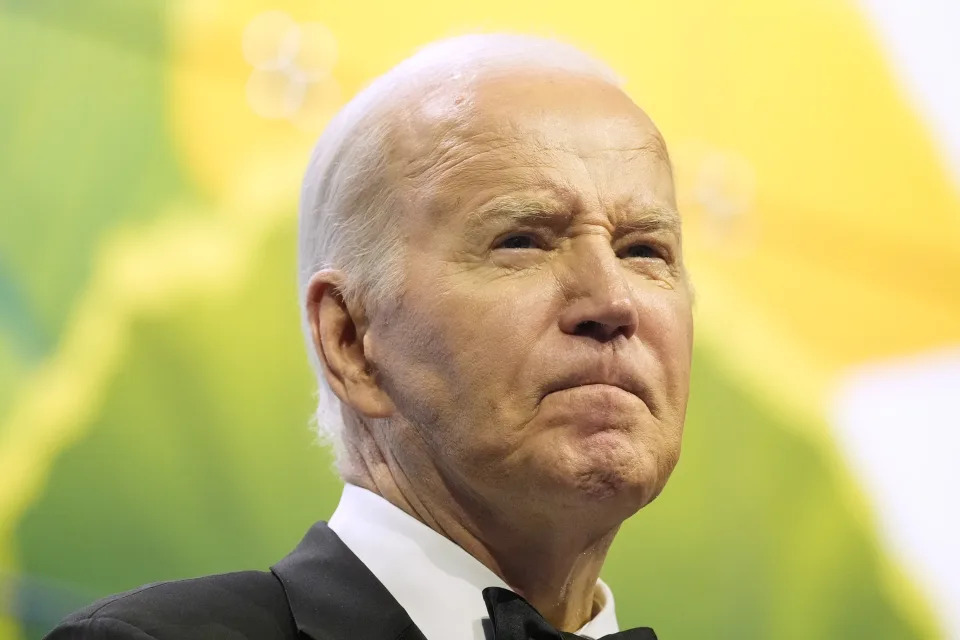

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Joe Biden marked this week's 70th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision that struck down institutionalized racial segregation in public schools by welcoming plaintiffs and family members in the landmark case to the White House.

The Oval Office visit Thursday to commemorate the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision to desegregate schools comes with Biden stepping up efforts to highlight his administration's commitment to racial equity.

The president courted Black voters in Atlanta and Milwaukee this week with a pair of Black radio interviews in which he promoted his record on jobs, health care and infrastructure and attacked Republican Donald Trump.

Biden is scheduled Friday to deliver remarks at the National Museum of African American History and Culture and — along with Vice President Kamala Harris — meet with the leaders of the Divine Nine, a group of historically Black sororities and fraternities. And the president on Sunday is set to deliver the commencement address at Morehouse College, the historically Black college in Atlanta, and speak at an NAACP gala in Detroit.

During Thursday's visit by litigants and their families, the conversation was largely focused on honoring the plaintiffs and the ongoing battle to bolster education in Black communities, according to the participants.

“He commended them for changing our nation for the better and committed to continue his fight to move us closer to the promise of America,” White House senior adviser Stephen Benjamin told reporters following the meeting.

Biden faces a difficult reelection battle in November and is looking to repeat his 2020 success with Black voters, a key bloc in helping him beat Trump. But the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research's polling from throughout Biden’s time in office reveals a widespread sense of disappointment with his performance as president, even among some of his most stalwart supporters, including Black adults.

“I don’t accept the premise that there’s any erosion of Black support” for Biden, said NAACP President Derrick Johnson, who took part in the Oval Office visit. "This election is not about candidate A vs. candidate B. It’s about whether we have a functioning democracy or something less than that."

Among those who took part in the meeting were John Stokes, a Brown plaintiff; Cheryl Brown Henderson, whose father, Oliver Brown, was the lead plaintiff in the Brown case; and Adrienne Jennings Bennett, a plaintiff in Boiling v. Sharpe, which was argued at the same time and outlawed segregation of schools in Washington, DC. Plaintiffs and family members of litigants of five cases that were consolidated into the historic Brown case took part in the meeting.

The Brown decision struck down an 1896 decision that institutionalized racial segregation with so-called “separate but equal” schools for Black and white students, by ruling that such accommodations were anything but equal.

Brown Henderson said one of the meeting participants called on the president to make May 17, the day the decision was delivered, an annual federal holiday. She said Biden also recognized the courage of the litigants.

“He recognized that back in the fifties and the forties, when Jim Crow was still running rampant, that the folks that you see here were taking a risk when they signed on to be part of this case,” she said. “Any time you pushed back on Jim Crow and segregation, you know, your life, your livelihood, your homes, you were taking a risk. He thanked them for taking that risk.”

The announcement last month that Biden had accepted an invitation to deliver the Morehouse graduation address triggered peaceful student protests and calls for the university administration to cancel over Biden’s handling of the war between Israel and Hamas.

Biden in recent days dispatched Benjamin to meet with Morehouse students and faculty.

Benjamin told reporters Thursday that the situation in the Middle East was among the issues he discussed with students and faculty during the visit.

No comments:

Post a Comment