U$A

Gun deaths among children and teens have soared – but there are ways to reverse the trend

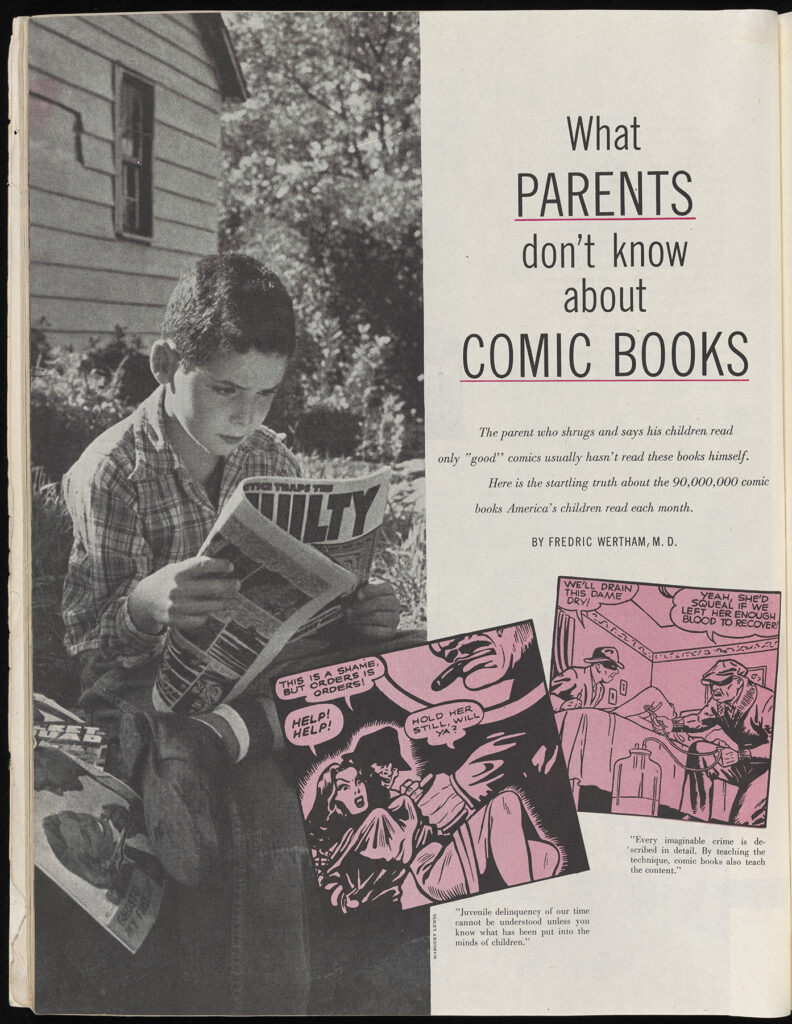

Cable locks can help prevent against accidental shootings.

Rookman / Getty Images

Trends in firearm deaths

The latest study is based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This data also provides information on whether firearm deaths were the result of homicide, suicide or unintentional shootings.

Get news that’s free, independent and based on evidence.Sign up for newsletter

We have seen increases over time in all three areas. The steepest increase has been in the rate of firearm homicides, which doubled over the decade to 2021, reaching 2.1 deaths per 100,000 children and teens, or about 1,500 fatalities annually. Firearm-involved suicides have also increased steadily to 1.1 deaths per 100,000 children and teens in 2021.

Whereas the proportion of youth firearm-involved deaths due to unintentional shootings is typically highest during childhood, the share of gun deaths due to suicide peaks in adolescence.

In 2021, homicide was the most common form of firearm-involved deaths in almost every age group under the age of 18, with an exception of 12- and 13-year-olds, in which suicide was the leading cause of firearm fatalities.

Racial disparities in firearm deaths, which have been present for multiple generations, are also expanding, research shows.

Black children and teens are now dying from firearms at around 4.5 times the rate of their white peers.

This disparity is the consequence of structural factors, including the effects of systemic racism and economic disinvestment within many communities. Addressing racial disparities in firearm-involved deaths will require supporting communities and disrupting inequity by addressing long-term underfunding in Black communities and punitive policymaking.

More research is needed to fully understand why firearm-involved deaths are universally increasing across homicide, suicide and unintentional deaths. The COVID-19 pandemic and its exacerbation of social inequities and vulnerabilities likely explain some of these increases.

Support structures

In addition to ongoing focused prevention efforts, hospital-, school- and community-based interventions that support youth in advancing social, emotional, mental, physical and financial health can reduce the risk of firearm deaths. Such measures include both creating opportunities for children and teens – building playgrounds, establishing youth programs and providing access to the arts and green spaces – and community-level improvements, such as improved public transportation, economic opportunities, environmental safety conditions and affordable and quality housing. Allocating resources toward these initiatives is an investment in every community member’s safety.

Over the past decade, we have seen an 87% increase in firearm-involved fatalities among children and teens in the United States. But we also have the strategies and tools to stop and reverse this troubling trend.

THE CONVERSATION

Published: October 16, 2023

Firearm injuries are now the leading cause of death among U.S. children and teens following a huge decadelong rise.

Analyses published on Oct. 5, 2023, by a research team in Boston found an 87% increase in firearm-involved fatalities among Americans under the age of 18 from 2011 to 2021.

Such an increase is obviously very concerning. But as scholars of adolescent health and firearm violence, we know there are many evidence-based steps that elected officials, health care professionals, community leaders, school administrators and parents can implement to help reverse this trend.

Firearm injuries are now the leading cause of death among U.S. children and teens following a huge decadelong rise.

Analyses published on Oct. 5, 2023, by a research team in Boston found an 87% increase in firearm-involved fatalities among Americans under the age of 18 from 2011 to 2021.

Such an increase is obviously very concerning. But as scholars of adolescent health and firearm violence, we know there are many evidence-based steps that elected officials, health care professionals, community leaders, school administrators and parents can implement to help reverse this trend.

Trends in firearm deaths

The latest study is based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This data also provides information on whether firearm deaths were the result of homicide, suicide or unintentional shootings.

Get news that’s free, independent and based on evidence.Sign up for newsletter

We have seen increases over time in all three areas. The steepest increase has been in the rate of firearm homicides, which doubled over the decade to 2021, reaching 2.1 deaths per 100,000 children and teens, or about 1,500 fatalities annually. Firearm-involved suicides have also increased steadily to 1.1 deaths per 100,000 children and teens in 2021.

Whereas the proportion of youth firearm-involved deaths due to unintentional shootings is typically highest during childhood, the share of gun deaths due to suicide peaks in adolescence.

In 2021, homicide was the most common form of firearm-involved deaths in almost every age group under the age of 18, with an exception of 12- and 13-year-olds, in which suicide was the leading cause of firearm fatalities.

Racial disparities in firearm deaths, which have been present for multiple generations, are also expanding, research shows.

Black children and teens are now dying from firearms at around 4.5 times the rate of their white peers.

This disparity is the consequence of structural factors, including the effects of systemic racism and economic disinvestment within many communities. Addressing racial disparities in firearm-involved deaths will require supporting communities and disrupting inequity by addressing long-term underfunding in Black communities and punitive policymaking.

More research is needed to fully understand why firearm-involved deaths are universally increasing across homicide, suicide and unintentional deaths. The COVID-19 pandemic and its exacerbation of social inequities and vulnerabilities likely explain some of these increases.

How to reduce gun fatalities

Reducing young people’s access to unsecured and loaded firearms can prevent firearm-involved deaths across all intents — including suicide, homicide and unintentional shootings.

Gun-owning parents can help by storing all firearms in a secure manner – such as in a locked gun safe or with a trigger or cable lock – and unloaded so they are not accessible to children or teens within the household.

Data shows that only one-third of firearm-owning households with teens in the U.S. currently store all their firearms unloaded and locked.

In addition to locking household firearms, parents should consider storing a firearm away from the home, such as in a gun shop or shooting range, or temporarily transferring ownership to a family member if they have a teen experiencing a mental health crisis.

Families, including those that don’t own firearms, should also consider how firearms are stored in homes where their children or teens may spend time, such as a grandparent’s or neighbor’s house.

Community-based and clinical programs that provide counseling on the importance of locked storage and provide free devices are effective in improving the ways people store their firearms. In addition, researchers have found that states with child access prevention laws, which impose criminal liability on adults for negligently stored firearms, are associated with lower rates of child and teen firearm deaths.

Reducing the number of young people who carry and use firearms in risky ways is another key step to prevent firearm deaths among children and teens. Existing hospital- and community-based prevention services support this work by identifying and enrolling youth at risk in programs that reduce violence involvement, the carrying of firearms and risky firearm behaviors.

While researchers are currently testing such programs to understand how well they work, early findings suggest that the most promising programs include a combination of reducing risky behaviors – through, for example, nonviolent conflict resolution; enhancing youth engagement in pro-social activities and with positive mentors; and supporting youth mental health.

Reducing young people’s access to unsecured and loaded firearms can prevent firearm-involved deaths across all intents — including suicide, homicide and unintentional shootings.

Gun-owning parents can help by storing all firearms in a secure manner – such as in a locked gun safe or with a trigger or cable lock – and unloaded so they are not accessible to children or teens within the household.

Data shows that only one-third of firearm-owning households with teens in the U.S. currently store all their firearms unloaded and locked.

In addition to locking household firearms, parents should consider storing a firearm away from the home, such as in a gun shop or shooting range, or temporarily transferring ownership to a family member if they have a teen experiencing a mental health crisis.

Families, including those that don’t own firearms, should also consider how firearms are stored in homes where their children or teens may spend time, such as a grandparent’s or neighbor’s house.

Community-based and clinical programs that provide counseling on the importance of locked storage and provide free devices are effective in improving the ways people store their firearms. In addition, researchers have found that states with child access prevention laws, which impose criminal liability on adults for negligently stored firearms, are associated with lower rates of child and teen firearm deaths.

Reducing the number of young people who carry and use firearms in risky ways is another key step to prevent firearm deaths among children and teens. Existing hospital- and community-based prevention services support this work by identifying and enrolling youth at risk in programs that reduce violence involvement, the carrying of firearms and risky firearm behaviors.

While researchers are currently testing such programs to understand how well they work, early findings suggest that the most promising programs include a combination of reducing risky behaviors – through, for example, nonviolent conflict resolution; enhancing youth engagement in pro-social activities and with positive mentors; and supporting youth mental health.

Support structures

In addition to ongoing focused prevention efforts, hospital-, school- and community-based interventions that support youth in advancing social, emotional, mental, physical and financial health can reduce the risk of firearm deaths. Such measures include both creating opportunities for children and teens – building playgrounds, establishing youth programs and providing access to the arts and green spaces – and community-level improvements, such as improved public transportation, economic opportunities, environmental safety conditions and affordable and quality housing. Allocating resources toward these initiatives is an investment in every community member’s safety.

Over the past decade, we have seen an 87% increase in firearm-involved fatalities among children and teens in the United States. But we also have the strategies and tools to stop and reverse this troubling trend.

Authors

Patrick Carter

Co-Director, Institute for Firearm Injury Prevention; Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine, University of Michigan

Disclosure statement

Rebeccah Sokol receives funding from the National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to conduct research to prevent violence.

Marc A. Zimmerman receives funding from NIH, CDC, BJA, & foundations.

Patrick Carter receives funding from NIH and CDC for conducting firearm-related prevention research.

Co-Director, Institute for Firearm Injury Prevention; Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine, University of Michigan

Disclosure statement

Rebeccah Sokol receives funding from the National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to conduct research to prevent violence.

Marc A. Zimmerman receives funding from NIH, CDC, BJA, & foundations.

Patrick Carter receives funding from NIH and CDC for conducting firearm-related prevention research.

Auto bodies are seen on the assembly line at a new factory of Chery Automobile, September 21, 2023, in Qingdao, China. (Photo via REUTERS)

Auto bodies are seen on the assembly line at a new factory of Chery Automobile, September 21, 2023, in Qingdao, China. (Photo via REUTERS)