Elizabeth Howell

Fri, November 10, 2023

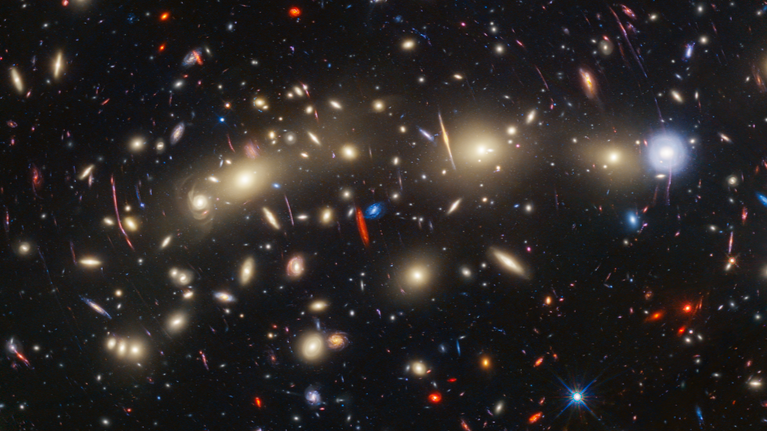

SpaceX's latest Starship prototype is rimmed with frost during a fueling test on Oct. 24, 2023.

Safety, not speed, should be the priority when conducting launch mishap investigations, members of a U.S Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) advisory committee say.

Amid reports of pressure from companies like SpaceX to add licensing staff to speed up approvals for new launches, FAA committee members instead urged caution Wednesday (Nov. 8) during a livestreamed meeting of the agency's Commercial Space Transportation Advisory Committee (COMSTAC).

"We've got to put safety first," Polly Trottenberg, deputy secretary at the U.S. Department of Transportation, emphasized. Paraphrasing Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, she said the FAA is often told "to move at exactly the speed of Silicon Valley. I know there's the 'move fast and break things' motto. I'm kind of the 'move fast and fix things' motto."

Still, Trottenberg acknowledged there can be a "conservatism" in the public sector, where "failure is swiftly punished" among politicians. She emphasized that safety cannot be compromised. But, she added, "we recognize that we need to find ways to ensure that, if we're not moving at the speed of industry, that we're moving faster where we can."

Related: FAA wraps up safety review of SpaceX's huge Starship rocket

COMSTAC was established in 1984 to report "on critical matters concerning the U.S. commercial space transportation industry" to the FAA administrator, according to the committee's documentation.

The membership includes not only senior executives from commercial space transportation, but also representatives from fields such as academia, the satellite industry, local and state government and companies that provide services such as insurance and legal matters.

As an advisory group to the FAA, COMSTAC plays no active role in evaluating "mishaps" that arise from failed commercial spaceflight launches. Committee members were also careful during Wednesday's meeting not to discuss ongoing investigations, including that of SpaceX. The company's debut Starship space launch in April saw the spacecraft spin out of control high over coastal Texas. SpaceX deliberately detonated the spacecraft, scattering debris over an environmentally sensitive area.

The FAA announced Oct. 31 that it had wrapped up the safety review of Starship, which examined the risks the launch poses to public health and safety. An environmental review with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is still ongoing, however. Meanwhile, Starship has performed several static fires, and SpaceX has emphasized that the system could launch as soon as mid-November if the regulators approve.

SpaceX has had mixed feelings about the FAA approval process over the years. For example, SpaceX founder Elon Musk said in 2021 on Twitter — now rebranded after Musk's 2022 takeover as X — that the FAA's space division has "a fundamentally broken regulatory structure," as the rules are based on "a handful of expendable launches per year from a few government facilities."

However, on Sept. 8 of this year, in discussing the 2023 relicensing of Starship, Musk posted hat it is "rare" for the FAA "to cause significant delays in launch [as] overwhelmingly, the responsibility is ours." But, on Sept. 5, he noted that Starship was "ready to launch" and is only "awaiting FAA license approval." SpaceX senior officials also told Ars Technica in October, speaking on background, that they want the FAA to double agency licensing staff.

Related: SpaceX's giant Starship vehicle towers above turquoise waters in gorgeous photo

SpaceX's Starship explodes minutes after launch

The FAA leads the investigation of all mishaps that did not, or plausibly could not, result in "a fatality or serious injury to any person;" in cases where such injuries or deaths would be possible, responsibility is led by the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board. Licensing for systems like Starship also can involve multiple government agencies or groups, as the ongoing environmental investigation shows.

Committee members acknowledged that there are more space systems than ever and that launch rates are accelerating. While companies would like the FAA to move faster, however, safety must remain the primary consideration, said the agency's Michael O'Donnell at the same meeting.

"It's really about applying the regulations reasonably so that you can innovate and you can do things differently," said O'Donnell, the FAA's deputy associate administrator for commercial space transportation. "One thing I've learned is the difference between aviation and space is the tolerance for mishaps. On the space side, it's a very different world."

He explained that the aviation industry tends to fly "very similar types of vehicle," while in spaceflight, there's customization: "every single vehicle is unique." The custom builds are part of what makes the licensing process so complex, he emphasized.

O'Donnell acknowledged, however, that the FAA's flat budget for spaceflight investigation needs to accommodate a burgeoning launch industry "an order of magnitude greater than it was five years ago." (To cite just one example, SpaceX has launched 80 orbital missions already in 2023, quadruple its 2018 rate.)

One solution may be for the companies to share safety data along with their "risk acceptance" for certain systems, ranked perhaps between low, medium and high. O'Donnell said this may allow industry and the FAA alike to "then make the determination what the severity is, the likelihood of it (a mishap) happening, and then working from that and trying to build consensus about what the severity is, what the likelihood is, and then work together."

Related: Do space tourists really understand the risk they're taking?

Blue Origin's New Shepard vehicle suffered an anomaly during an uncrewed launch on Sept. 12, 2022. This screengrab shows New Shepard just before the vehicle's capsule successfully engaged its emergency escape system.

O'Donnell noted that the FAA and industry would need to agree on what constitutes "safety data," which has been a sticking point. Industry reticence to such sharing has been brought up repeatedly: given each vehicle is so unique, it is difficult to anonymize information, representatives heard at meetings of COMSTAC in October 2018 and again in May 2023.

A Rocket Lab Electron rocket launches a Capella Space satellite on Sept. 19, 2023. The rocket suffered an anomaly, resulting in the loss of the satellite.

RELATED STORIES:

— FAA wraps up safety review of SpaceX's huge Starship rocket

— FAA proposes rule to reduce space junk in Earth orbit

— FAA closes investigation of Blue Origin launch failure

While SpaceX has been getting most of the attention from the media concerning mishaps, it's not the only one the agency addressed in 2023. The FAA closed five space mishap investigations this year — such as SpaceX's Starship, and a 2022 incident with an uncrewed Blue Origin New Shepard flight — and still has three that are open, O'Donnell said.

One example of an active investigation is that of Rocket Lab, which had a failure on Sept. 19 with its Electron rocket that caused the loss of a commercial Earth observation satellite. An electrical arc within a key power supply system was likely at fault, and the company hopes to fly in late November. (The mishap inquiry continues, but the FAA did tell Rocket Lab its launch license is still active, company representatives recently said.)