Isaac Schultz

Fri, November 10, 2023

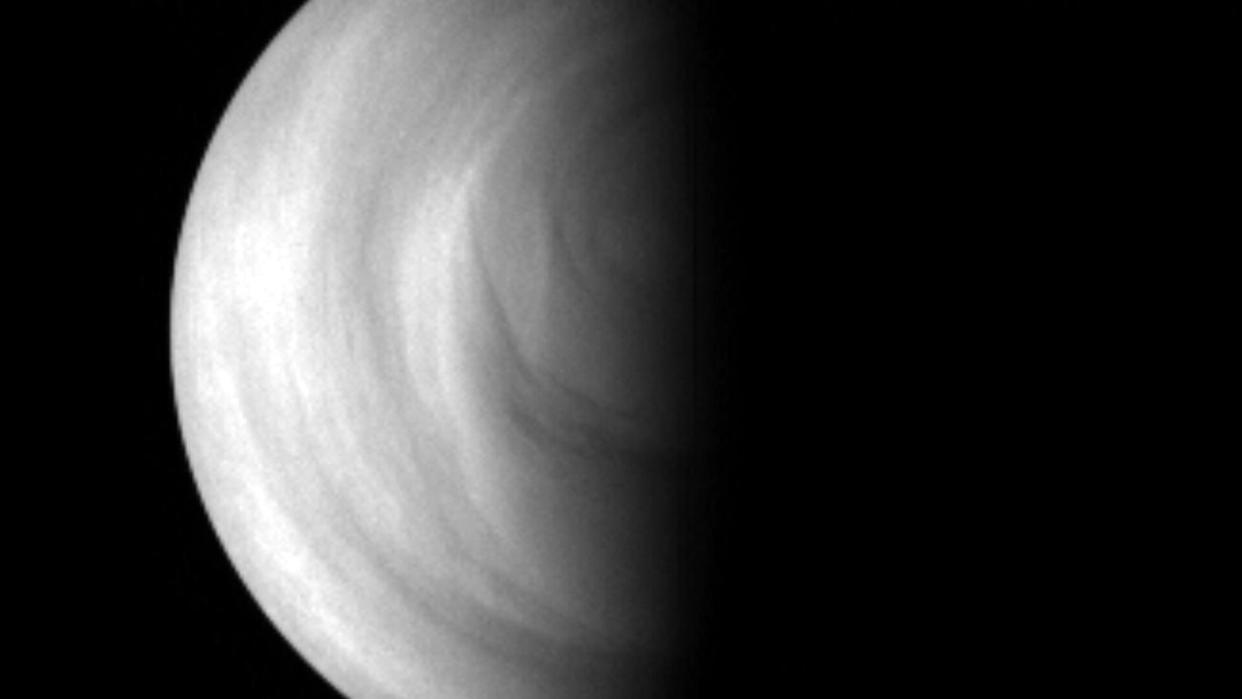

Venus' cloudy skies.

While air is a gaseous delight unique to Earth, a team of astrophysicists have made a satisfying discovery: the direct observation of atomic oxygen on Venus’ dayside, confirming that the element crucial for our existence exists on both sides of the hellish planet.

About 96% of the atmosphere on the second planet from the Sun is made up of carbon dioxide, a smidge of other gasses including nitrogen, and practically no oxygen. But there is some oxygen, and some of the element was found previously on Venus’ dark side. Now, the same can be said of the world’s scalding sunny side.

Venus wasn’t always so uncomfortable, with an average temperature of 850° Fahrenheit and a toxic atmosphere rich with clouds of sulfuric acid. The planet is sometimes referred to as Earth’s fraternal twin, due to the similarities and obvious differences between the two worlds. Venus may have had oceans once, which evaporated when the planet got stuck in a runaway greenhouse effect (though later research indicated what may have been water oceans were actually lakes of lava).

“Venus is not hospitable, at least for organisms we know from Earth,” Heinz-Wilhelm Hübers, a physicist at the German Aerospace Center and lead author of the study, told Reuters. “We are still at the beginning of understanding the evolution of Venus and why it is so different from Earth.”

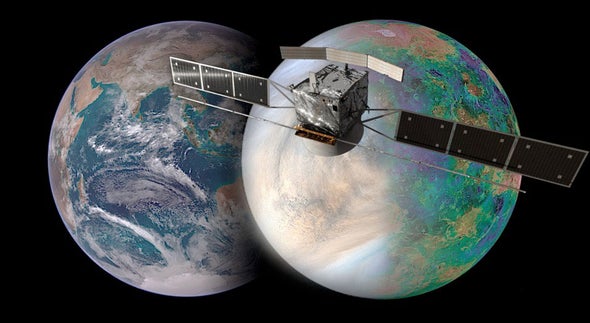

In quick succession in Spring 2021, NASA and ESA announced three missions focused on Venus; the United States’ space agency had greenlit VERITAS and DAVINCI+, while the Europeans announced the Venus orbiter EnVision. The VERITAS mission has since been delayed due to funding issues, but space agencies remain committed to better understanding the yellowish world, which could offer insights into Earth’s own evolution over its 4.6-odd billion years of existence.

In other words, we’re setting ourselves up for a whole new portrait of the second planet from the Sun, which will come into focus around 2030.

More: Why Venus Is Soon to Be the Most Exciting Place in the Solar System

Oxygen detected in Venus' hellish atmosphere

Joanna Thompson

Fri, November 10, 2023

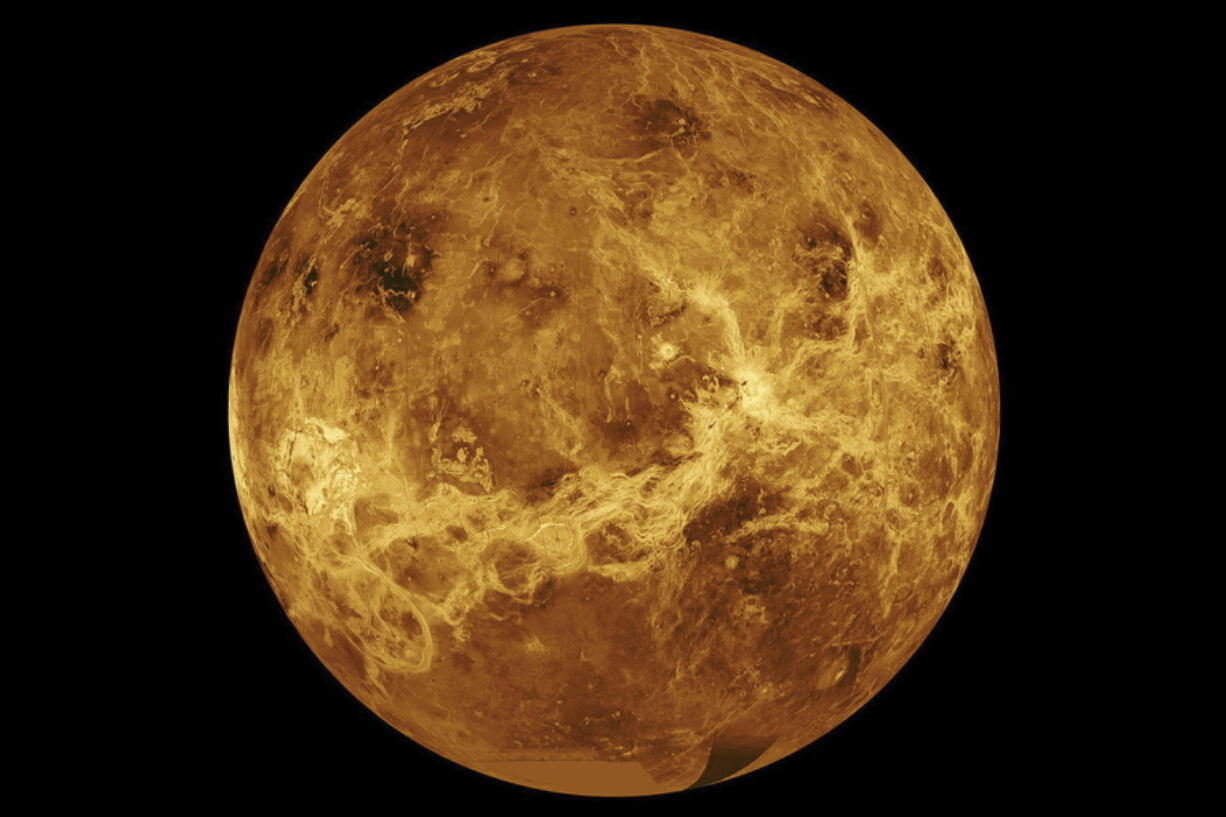

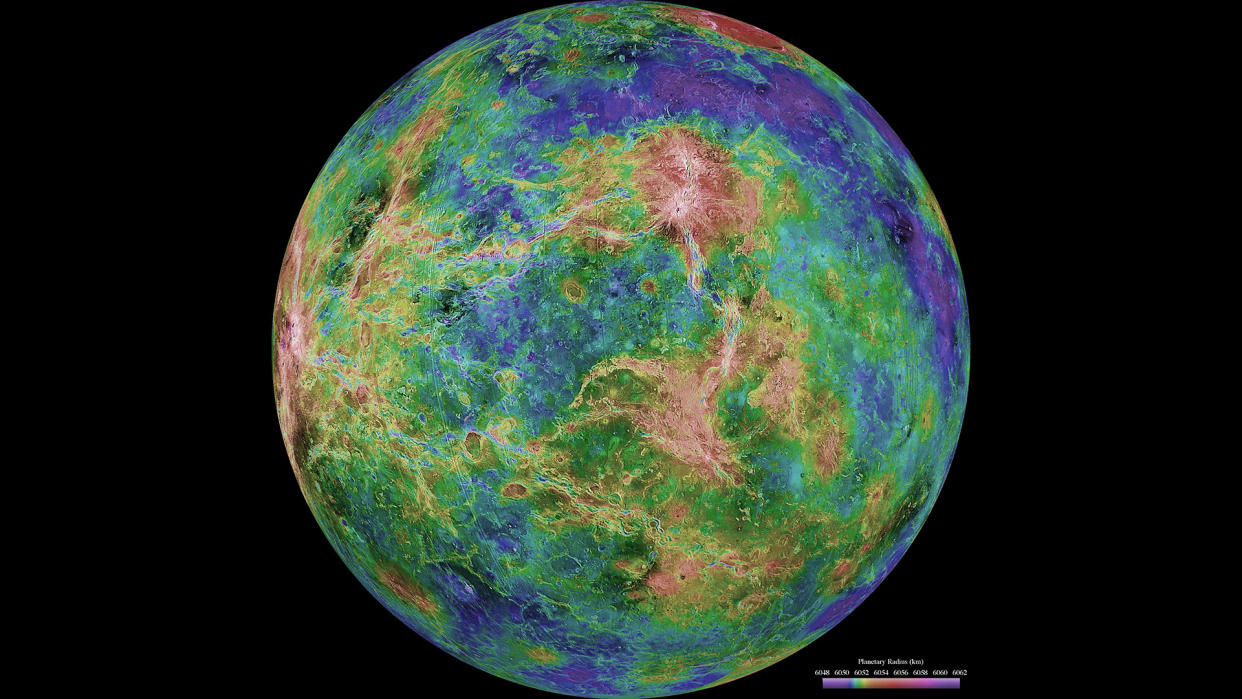

Hemispheric view of Venus.

Venus' atmosphere is notoriously hellish. Its air is corrosive and hot enough to melt lead. Its billowing clouds are poisonous to humans. Sometimes, it rains acid. But researchers just discovered that, sandwiched between layers of toxic gas, this inhospitable atmosphere contains a thin layer of molecular oxygen.

Historically, Venus has received far less scientific attention than Earth's other neighbor, Mars. Recent reports that the organic compound phosphine may (or may not) exist in the Venusian clouds, however, have sparked new interest in studying the planet.

The new measurements come courtesy of NASA's Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), a Boeing 747 that the agency retrofitted with a 2.7-meter (8.9 feet) infrared telescope. A team of German astrophysicists pored through data from SOFIA, focusing on 17 positions in Venus' atmosphere, on both the planet's dayside and nightside. They detected molecular oxygen — a gas composed of nonbonded oxygen atoms — in all of them. The results were published Nov. 7 in the journal Nature Communications.

But that doesn't mean astronauts would be able to breathe oxygen on Venus just as they would on Earth. Molecular oxygen is distinct from the oxygen that we breathe on our planet: Whereas breathable oxygen consists of two bonded oxygen atoms, creating the molecule O2, molecular oxygen is a soup of single, free-floating oxygen atoms. If we tried to breathe it, it would react too easily with the tissues in our lungs and wouldn't make it to our bloodstream.

Oxygen had been previously observed on the nightside of Venus, but this marks the first time researchers have detected it in the day-lit regions as well. The researchers suspect that the molecular oxygen builds up as the sun's heat breaks down carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide molecules. Winds high in the atmosphere then whisk it over to the planet's nightside, where the free oxygen atoms gradually react with other elements.

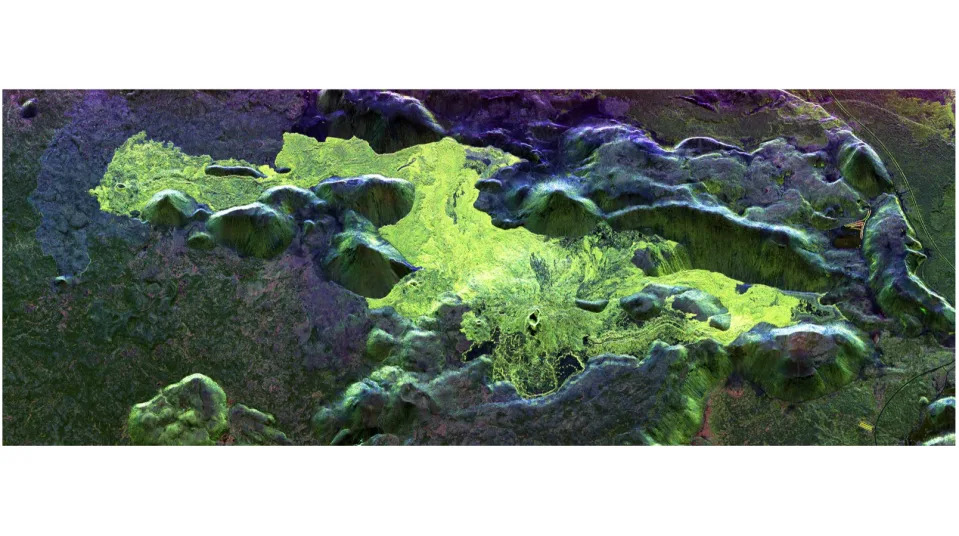

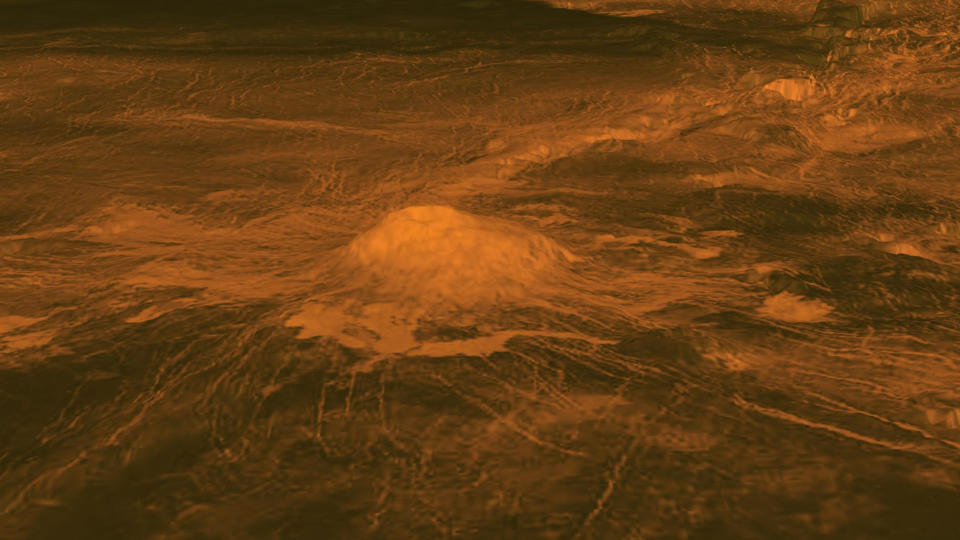

Surface warmth on a Venus volcano.

RELATED STORIES

—Mysterious flashes on Venus may be a rain of meteors, new study suggests

—Venus has thousands more volcanoes than we thought, and they might be active

—1st evidence of recent volcanic activity on Venus detected in groundbreaking study

The molecular oxygen layer also probably has a slight cooling effect on the upper layers of Venus' atmosphere. This modest cooling isn't enough to offset the planet's runaway greenhouse effect, but it does hint at Venus' milder, more pleasant past.

The finding also highlights how much scientists still have to learn about Earth's hostile "twin." With two upcoming NASA missions, as well as one helmed by the European Space Agency, Venus is about to receive a lot more attention, which may mean more discoveries in the near future.

Between Venus' atmospheric currents, a layer of reactive oxygen

Conor Feehly

Thu, November 9, 2023

This image of the Venus southern hemisphere illustrates the terminator – the transitional region between the dayside (left) and nightside of the planet (right).

Today, our sister planet Venus resembles an environment as close to hell as one can imagine. Surface temperatures on the amber world soar to 450 degrees Celsius (842 degrees Fahrenheit), while about 96% of the planet's crushing atmosphere is made up of carbon dioxide. Once upon a time, however, Venus may have resembled something much closer to our balmy home — Earth.

That was until runaway greenhouse gas processes, likely triggered by volcanic activity, sent Venus on a trajectory that resulted in the noxious neighbor we see today. However, in new research that furthers our understanding of the planet's atmospheric evolution, astronomers announced they've directly detected the presence of atomic oxygen in both the day and night side of the Venusian atmosphere.

Atomic oxygen is the highly reactive chemical cousin of molecular oxygen (the stuff we breathe and simply refer to as oxygen.) Unlike molecular oxygen, or O2, made of oxygen atom pairs, atomic oxygen is composed of individual oxygen atoms.

Related: The deadly atmosphere on Venus could help us find habitable worlds. Here's how

At risk of simplification, those individual oxygen atoms are therefore always ready to pair with another atom or molecule. That's what makes atomic oxygen so reactive — pairing up would make a single oxygen atom more stable, so these oxygen singlets want to react. This is also why molecular oxygen isn't as reactive. Its oxygen atoms are all buddied up.

Detecting atomic oxygen

The team of astronomers led by Heinz-Wilhelm Hübers, director of the German Aerospace Center, used the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) — an airborne observatory, to collect data on Venus' atmosphere.

"We were able to plan a flight route which allowed us to observe Venus (which is at low elevation) shortly before sunset for three days, each day for about 20 minutes," Hübers told Space.com.

Onboard SOFIA was the upGREAT Terahertz heterodyne spectrometer, which was used for the observations. Hübers explained that this particular spectrometer is especially sensitive to the frequency and wavelength of atomic oxygen, which are 4.74 terahertz and 63.2 microns, respectively.

The atmosphere on Venus houses two strong currents. The lower of the two sits below 70 kilometers (43.5 miles) in altitude, where the equivalent of hurricane-force winds on Earth blow against the direction of Venus' rotation. The higher current sits above 120 kilometers (74.6 miles) in altitude with winds that flow in the direction of the planet's rotation.

"A layer of atomic oxygen exists between these two opposing atmospheric currents," Hübers says.

This layer of atomic oxygen, the scientists believe, is produced by ultraviolet radiation coming from the sun, which breaks down carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide in Venus' atmosphere into atomic oxygen and other molecules. In this process, known as photolysis, high-energy photons collide with carbon molecules to force the molecules to essentially rip apart.

Because the atomic oxygen is predominantly concentrated around 100 kilometers (62 miles) in altitude between the two circulation patterns, it's possible these currents play a role in distributing the substance around the planet. However, Hübers says the team couldn't quite quantify this yet with their current measurements.

Although, he does mention they observed a local enhancement of atomic oxygen on the planet's nightside, close to the line which separates day and night, known as the "terminator." Possibly, this enhancement could be caused by the terminator's winds.

Should future missions to Venus be worried?

While atomic oxygen was detected in Venus' atmosphere, it's worth noting that the concentration was much lower than what we find in Earth's atmosphere. Earth's atmosphere has roughly 10 times more atomic oxygen than Venus' does. In fact, the relatively high concentration of atomic oxygen in the atmosphere around our planet is considered a threat — these particles are responsible for some corrosion of satellites in Low Earth Orbit (LEO), including the International Space Station.

The presence of the highly reactive oxygen on Venus, therefore, shouldn't pose too much of a corrosive threat to any future satellites that get sent there.

"Besides that, it is very interesting to measure the altitude distribution of the atomic oxygen in the Venusian atmosphere in order to understand the chemistry and physics of the atmosphere better and to compare it with Earth," says Hübers.

Atomic oxygen, day and night

Related Stories:

— Planet Venus: 20 interesting facts about the scorching world

— Life on Venus? Intriguing molecule phosphine spotted in planet's clouds again

— 'Lightning' on Venus is actually meteors burning up in planet's atmosphere, study says

It was important for researchers to collect data from both the day and night side of Venus, largely because the planet rotates at an excruciatingly slow pace — one day on Venus lasts 243 Earth days, or 5,832 hours.

According to Hübers, the most likely explanation for this slow rotation is that the gravity of the sun induced tides on Venus during an early stage of the planet's lifecycle, when it was more or less a liquid, molten body. The rotational energy of Venus possibly worked against the formation of tides on the world due to that molten structure, and eventually, scientists think it slowed to its current-day rotational speed.

Ultimately, the results from the study paint a picture of the Venusian atmosphere as starkly different to our own, and highlight how small differences in our past can accumulate over time to result in dramatically different futures.

The study was published Tuesday (Nov. 7) in the journal Nature Communications.